Ludwig Scheinbrum, the son of Alexander and Rosa Scheinbrum, was born on June 29, 1910 in Vienna, Austria. He completed high school and Business College before the war. He was in Stein-in-d.-Donan Labor camp in Austria from February 12, 1934 to December 24, 1935. He was in Morzinplatz Concentration Camp from March-April 1938 and then was transferred to Dachau and from there to Buchenwald, where he remained for the entire duration of the war (November 1938 to April 1945). He was liberated by the U.S. Army at Buchenwald on April 11, 1945. His parents and brother survived the war, having escaped to the United States.

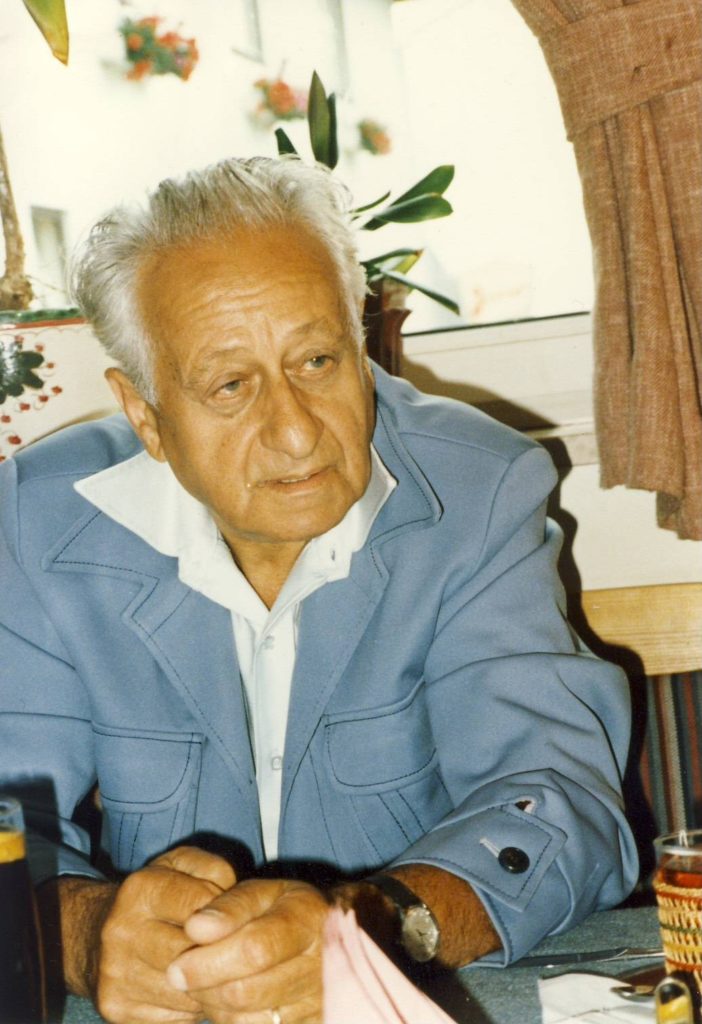

Ludwig Scheinbrum

Mapping Ludwig's Life

Click on the location markers to learn more about Ludwig. Use the timeline below the map or the left and right keys on your keyboard to explore chronologically. In some cases the dates below were estimated based on the oral histories.

Read Ludwig's Oral History Transcripts

Read the transcripts by clicking the red plus signs below.

Tape 1 - Side 1 (Kalfus)

KALFUS: So actually you started to – you might want to just mention that you’re… I would be interested in hearing about your impressions in Washington – – what you objected to.

SCHEINBRUM: Don’t get me in trouble. (laughter)

KALFUS: No, I won’t get you in trouble. (laughter)

SCHEINBRUM: They still send papers and booklets. I had to spend…make a contribution of $100.00 here and I can’t do that I’m retired. I don’t make any money to spend $100.00 to give them away. I can’t do it. I’d like to do it, but my gosh, now they want to make a museum. Maybe you know about it.

KALFUS: Sure

SCHEINBRUM: I saw this building and now they want to put money…money…money. I can’t do it. Maybe they’ll get a few more rich guys what can help.

KALFUS: Oh sure, I can understand that. You had mentioned to me that …what is your background? I would be interested in knowing a little bit about your life in Vi…You were in Vienna born and raised in Vienna.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. My parents came from Russia – my mother from Odessa. My father was in the Russian Army under the Czar Nicholas. I think so – I forgot. And 1907 or 1905 he left Russia and was coming to Vienna.

KALFUS: So you were born in…

SCHEINBRUM: I was born in Vienna in 1910. And since then I didn’t leave the country. I was…

KALFUS: So you went to school in Vienna?

SCHEINBRUM: I went to school in Vienna, you know for 8 years.

KALFUS: Were your parents – were Jewish?

SCHEINBRUM: Yes, yes, yes. Oh yeah. And after then I was coming out from school, I learned a trade in jewelry, trading. At first I want to be a salesman, I don’t want to be, but my parents thought it’s a good deal. A salesman – I couldn’t lie to the people (LAUGHTER) to sell them junk, you know. I quit that.

KALFUS: What kind of a schooling was that?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, that is the Mittlerer Reife, the Volksschule and the Buergerschule. That’s five years first and three years after that. If you learn a trade you have to go in a trade school for three years. So that’s what I was doing. I couldn’t sell anything where I know it’s not good. I couldn’t talk to people when I know it’s a piece of junk. I like to work with my hands.

KALFUS: So you went into the jewelry business?

SCHEINBRUM: Right, since then I work all the time.

KALFUS: How long did you…did you work then in Vienna, also in your trade?

SCHEINBRUM: Yes, yes, but now this trade was so bad business that I was the most time without a job. I worked maybe 20 hours.

KALFUS: What period was that?

SCHEINBRUM: It was from 1927 until ’33.

KALFUS: So the different time economically, in most of Europe.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, so I didn’t make any money. I don’t make any money to…to…buy me clothes or something. That’s what I made, I give it, most to my parents.

KALFUS: So you lived at the time with your parents?

SCHEINBRUM: With my parents, my brother too. My brother is still alive. He lives in Waco in Texas.

KALFUS: Oh you were one of two children?

SCHEINBRUM: Two yeah, yeah, yeah. I’m the youngest one. The young one – the baby. No more baby…74 years old. (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: Age has a strange way of equalizing everything. How many years older is your brother?

SCHEINBRUM: Two years older.

KALFUS: So you went to school then in Vienna?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah.

KALFUS: And lived with your parents’ right up until…

SCHEINBRUM: Up until…’38. In 1938 – until we was liberated from Germany. You know, I said ‘liberated’. I was 3 days free when they got me.

KALFUS: Amazing. Before you mention it, I just want to quickly ask something. What kind of religious background did you have in …

SCHEINBRUM: I’ll tell you the truth. When I was a little boy, 6 or 7, my father took a teacher to teach me ‘religion’ (LAUGHTER). I tell you the truth, I couldn’t read that stuff anyway. It was like shorthand or something. You had to write from the left to the right. No, I was 2 years or 3 years in school.

KALFUS: So you were bar mitzvah?

SCHEINBRUM: No.

KALFUS: You weren’t and your parents didn’t…

SCHEINBRUM: No, they didn’t make a big…no…my father, he was raised very religious in Russia and I remember what he told me. His father was a horse dealer and when he told me about the business with the poor farmers, he said, “I quit the religion”.

KALFUS: No, I think…I think that’s very interesting. I mean, you felt yourself – and the reason I ask that, is while in Austria, you felt yourself very much an Austrian and not a Jew. (OVERTALKS)

SCHEINBRUM: No I go to school and other friends were Gentiles and all we were raised together since I was 12 years, or 10 years old and I didn’t go in Hebrew school like other. I was raised together. We were going in one class and I still have 2 or 3 friends in Vienna, Jewish friends. One guy was 6 years in Russia, in a camp in Russia during the war and one was hiding the whole time in Vienna. One day here, one day there. yiddish_ The Gentiles hide him.

KALFUS: Right, Right. But so you didn’t belong to any Jewish youth group?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no.

KALFUS: Or any kind of Jewish community…or any kind of…and didn’t go to Synagogue there regularly?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no, no.

KALFUS: So that’s …weren’t you terribly surprised when, as you mentioned, they got you – so…

SCHEINBRUM: No. Uh, why they got me? You say, when they got me?

KALFUS: Right.

SCHEINBRUM: No it wasn’t the reason that I was Jewish. It was a different reason – a political. reason.

KALFUS: Can you discuss that, or…

SCHEINBRUM: Okay.

KALFUS: You don’t have to. Anything you don’t want to discuss, you don’t have to.

SCHEINBRUM: I don’t care. I don’t know if you know 1934. Can you go back 1934?

KALFUS: Sure.

SCHEINBRUM: To the Labor was against the government in Austria. I was…I was involved in that.

KALFUS: In the Labor party?

SCHEINBRUM: In the Labor party. I was involved in a ‘shoot out’ with the police, and I got 3 years. In 3 years, I made 18 months in solitary … and that’s the reason…

KALFUS: Where were you …where were you imprisoned?

SCHEINBRUM: By Vienna in a jail. _______________ They call it Schtein on the Danube, Stein on the Donau. I got through everything (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: And that was because of your political background? _______________

SCHEINBRUM: Could be background and maybe Jewish too. I don’t know.

KALFUS: Oh, it’s hard, it’s probably hard to separate that.

SCHEINBRUM: They didn’t give me any papers to sign. I didn’t sign anything. They picked me up from home after 3 days, and…

KALFUS: But the political imprisonment, what did the Party represent that you were…?

SCHEINBRUM: The Socialist Party. The S.S.P.E.

KALFUS: The Socialist Party?

SCHEINBRUM: The Socialist Party, not the Communist Party which was a different thing.

KALFUS: Right. And you were actually the party that was in power that you had the shoot out with?

SCHEINBRUM: No the Party wasn’t the power. There was, already under the Dollfuss.

KALFUS: Okay, so it was already under Nazi…

SCHEINBRUM: Under Dollfuss, we went underground.

KALFUS: Okay. So you were actually working as a…politically underground during that time.

SCHEINBRUM: That’s right.

KALFUS: And that was your first time that you were in prison?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah.

KALFUS: What year was that?

SCHEINBRUM: 1934, February 12, 1934.

KALFUS: Until ’30…?

SCHEINBRUM: I was released after2 years for good behavior, but I got, I had to report to the police every week, you know, until Hitler was coming in ’38.

KALFUS: What do you remember of that particular time, of ’38 when you…?

SCHEINBRUM: ’38? No, I was still working part-wise, part time by a Gentile. And the first thing we had to cut up behind little hakenkruyts, you know in silver. I cut up and cut up to make a living. I had to bring some money in. And after 3 days, when the job was over, they picked me up.

KALFUS: No preparation as far as…?

SCHEINBRUM: Nothing, nothing. I come home from work and they was waiting for me. Two SS men and a policeman.

KALFUS: And you think it was your political…?

SCHEINBRUM: I think so, yeah, I think they got the list already made up from all my friends who was involved in this.

KALFUS: And they all were taken?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah.

KALFUS: Your brother also was taken?

SCHEINBRUM: My brother too. He was in a…in a…in an evening school. They picked him up at school.

KALFUS: Where?

SCHEINBRUM: In an evening school. In a English school to learn English.

KALFUS: Oh, okay.

SCHEINBRUM: They picked him up. He was driving down to school and they picked him up at school.

KALFUS: What about your parents?

SCHEINBRUM: My parents didn’t have no trouble, but after then there was 4 weeks in the …by the Gestapo. They was released and they told me, “You’ve got 3 days to leave the country.” Now, where I’m going? I got no money. I don’t know anybody. I don’t have any idea of where I’m going. I was going home.

KALFUS: Exactly. It was almost like a death certificate.

SCHEINBRUM: No, that’s the reason they picked me up. My brother didn’t go home.

KALFUS: They picked you up after 3 days because you didn’t leave the country?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. I don’t know how they found out, but I’m going home. I’m going home. I got … I don’t know any language. Where am I going? My brother, he got to France and to Italy and some other places. He was hiding one year in Vienna, by Vienna, and after that had the chance to go to Italy and from Italy to the United States. In year 1941 he joined the army.

KALFUS: Which army?

SCHEINBRUM: The U.S. Army.

KALFUS: OVERTALK When did he get to the United States then?

SCHEINBRUM: In ’39, something like this.

KALFUS: And you didn’t get here until…?

SCHEINBRUM: ‘47

KALFUS: ’47. When you were, that particular time in ’38, when you were captured the first time and then let go and then captured again, did you have any anticipation as to the course of events? I mean, you were politically active, and you knew more probably about….

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, but I didn’t know that it would work out in a way like this. I figured that they were still honest people. I didn’t know. You see, you don’t know anything. The United States didn’t believe then, when people were saying here, at the beginning, that they were… killed people for nothing. The United States didn’t believe it.

KALFUS: Exactly.

SCHEINBRUM: They sent away, you know, they sent the ships away. They had to go back to Germany.

KALFUS: Right.

SCHEINBRUM: And they killed them over there.

KALFUS: Right. One was the S.S. St. Louis.

SCHEINBRUM: That’s right. I didn’t know too much.

KALFUS: The reason I’m asking you is because you were so politically active. You were probably were….

SCHEINBRUM: No, I wasn’t particularly active. I got no charge of anything, you know. But I was a member….

KALFUS: But you were involved.

SCHEINBRUM: ….of the Underground and I figured that when they called you, you have to go.

KALFUS: Right.

SCHEINBRUM: Until September or November ’38. They got the chance to leave the country but they had to leave everything.

KALFUS: They came to the United States?

SCHEINBRUM: They come to the United States, to San Francisco, until my mother… got her brother here, since 1906. They was living together about 8 months, 10 months, but living together with grown-up people in one…it didn’t work. My father got a job here in Washington in a cap making factory.

KALFUS: In where? In a …?

SCHEINBRUM: A cap maker.

KALFUS: Uh huh.

SCHEINBRUM: He got the job and my mother was coming back and …

KALFUS: And your brother then came 3 years, 2 or 3 years later then to the United States?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, before my parents.

KALFUS: Oh, he was here before your parents?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, sure, sure.

KALFUS: Oh, I understand now.

SCHEINBRUM: And after then he joined… he was living in….

KALFUS: In ’41 he joined the army.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah.

KALFUS: Pearl Harbor?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

KALFUS: Did you have, uh, I’m sorry, you wanted to say something?

SCHEINBRUM: No, that’s when my parents sent me the cards after the war for the boat to come over, you know.

KALFUS: Right.

SCHEINBRUM: But in the meantime, I met a girl over there and I told her…I told my parents, “If you can send 2 tickets, I will come.”

KALFUS: What did they do?

SCHEINBRUM: They sent 2 tickets. They got into debt to raise the money.

KALFUS: Right. Did you have any communicat…maybe we can backtrack now, and sort of talk about that period. I was…when you came to my class, I was just amazed when you talked about, I mean you spent literally the entire war in camps.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, more, more. 7 years.

KALFUS: 7 years. Maybe we can trace some of that. The second time you were captured, were you then sent to Dachau?

SCHEINBRUM: No, I was home. No, they put me again in the police station for a few days. From here they put us in an empty school. They sent the kids home and they surrounded the school from (with) police, not SS. And we stayed about 2 or 3 weeks in the school and from here, I was going to the railroad station, West Bahnhof in Vienna and on the train and going to Dachau.

KALFUS: How long were you in Dachau?

SCHEINBRUM: 6 months…in Dachau. I think from September, I was transferred to Buchenwald until the end of the war.

KALFUS: So you were in Buchenwald then for…?

SCHEINBRUM: Over 7 years.

KALFUS: Over 7 years. That’s just…, that’s just…

SCHEINBRUM: No, I was lucky. You know, in Vienna the people say, “Der Dumme hat’s Gluck,” if you be crazy, you’re lucky. Maybe I was too crazy that I was lucky. From 3,000 we survived, only 36.

KALFUS: How many?

SCHEINBRUM: From three thousand.

KALFUS: Now when you say 3,000, you refer to…?

SCHEINBRUM: From the train, in the same train where I was coming from Vienna to Dachau.

KALFUS: To Dachau.

SCHEINBRUM: And at the end of the war we got only 36 left.

KALFUS: Thirty-six left. That’s amazing. The others, many of those went to various concentration camps…?

SCHEINBRUM: Other camps and died from sickness and killed themselves and something, something.

KALFUS: When you say “lucky,” is that what you would attribute your survival to, or…?

SCHEINBRUM: I think so. I know a little bit, you know, how to sneak to stay alive.

KALFUS: Can you give me some examples?

SCHEINBRUM: You see, I don’t smoke. If I got the chance to get some cigarettes, I sold the cigarettes for food. In short, to say that I don’t care if the other guy wants to smoke and die, it’s his business. I want to stay alive.

KALFUS: Right. I mean, you had a real strong will to survive.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. The same with shoes. If you had shoe, it was no good. You got sore feet. And that’s another thing. I tried to get the best shoes what I could. I didn’t steal anything. There was nothing to steal. But I exchanged food, other things, for shoes.

KALFUS: Right. I mean you managed to, I mean…it was a question of survival all the time.

SCHEINBRUM: That’s right. From one day to the other. You don’t know what’s tomorrow.

KALFUS: Did you ever come to think you weren’t going to make it?

SCHEINBRUM: Oh, yes, yeah. Especially when they started in 1941 to transport Jews away from the camp and we know they was going to Auschwitz. We didn’t know exactly, officially, but…

KALFUS: Did you know that there were gas chambers in Auschwitz?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah.

KALFUS: You know that from the …?

SCHEINBRUM: The reason we know, was that clothes was coming back, and we found out through one SS man. He was very friendly to some people, of us. He got hanged in the Doctor Prozess in Nuremberg after then.

KALFUS: After the war?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, after the war. Wilhelm was his name. His name was Wilhelm. He helped me a lot. There was another big SS man…

KALFUS: It didn’t help that he had helped the prisoners?

SCHEINBRUM: It didn’t help, no.

KALFUS: I mean, he killed a lot also, I would think.

SCHEINBRUM: No, out of the whole Prozess, he didn’t kill anyone. But after the war, the men who were on trial at the prison, accused him of everything that I could think.

KALFUS: So people that you knew that…

SCHEINBRUM: That were still alive.

KALFUS: …were accusing him of things he didn’t do.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah.

KALFUS: That’s an interesting twist to the story. It’s usually the other…

SCHEINBRUM: There are other things, the Hauptsturmfuehrer, Dr. Hoven, he helped me a lot in the camp for years.

KALFUS: How did he help you?

SCHEINBRUM: I worked in the hospital for 5 years or 4 years.

KALFUS: As what? As an orderly? Or…?

SCHEINBRUM: As an orderly or stretcher bearer. I worked in the sick rooms, giving shots and this and this. And he helped me. He give me a job where I was away, and I didn’t have to report to the roll call.

KALFUS: Yeah, when you came to my class you mentioned… I will never forget that, you mentioned the roll call. And then you…maybe you can repeat that, because you mentioned, uh, that when somebody died in the – correct me if I am incorrect- when somebody died within a bunk, you tended to try to keep him, have him make the roll call so that you got his bread ration.

SCHEINBRUM: That’s right. We tried this, the food that they got, collect what they got and was given to other people.

KALFUS: So that’s another example of how to survive, by using every possible means.

SCHEINBRUM: Now the bodies are so thin that when they have to bring them up to the crematorium from the camp. They put two on a stretcher- one head here and one here, between the legs. I don’t know if you…maybe you don’t know how this works.

KALFUS: No, I would like you to tell me, because I…

SCHEINBRUM: OVERTALK The bread from the dead ones, I put on the bodies from the dead one, to deliver to other buildings for people who was waiting for bread. The whole pile, and the bread on them.

KALFUS: When you say you delivered it, I mean, you gave it away, or you…?

SCHEINBRUM: I gave it away.

KALFUS: Why didn’t you take it yourself?

SCHEINBRUM: I got enough.

KALFUS: You got enough because you were in the hospital, right? So that was pretty…

SCHEINBRUM: Yes. Everything that I got a chance to take. I showed you my…that picture from the camp?

KALFUS: Yes, I think you did.

SCHEINBRUM: With the round face?

KALFUS: No, I don’t…

SCHEINBRUM: I got some.

KALFUS: When you say a “round face”, you mean you weren’t starving?

SCHEINBRUM: No, in other words…blown up.(Yiddish)(LAUGHTER) I got so many papers, but I give away already to other people in East St. Louis I say, no, I’m crazy to say East St. Louis…to Germany, you know.

KALFUS: In the archives?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. (SHUFFLES PAPERS) It was funny thing, in ’44, I think. Does it have a date on it?

KALFUS: Uh huh.

SCHEINBRUM: I don’t know what date it is.

KALFUS: ’39.

SCHEINBRUM: ’39. The German Army was coming to the camp to recruit for the Army, who didn’t know that I am Jewish. When they found out I’m Jewish, they…

KALFUS: They wanted to recruit you from Buchenwald?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, the Army. That’s what they made for everybody what was each year, you know, when they found out I’m Jewish and they refused to take me into the Army and that’s it. The official paper that I’m not worthy to join the Army. They took a picture and that’s the way I looked. A blown up water…water. I was eating water soup all day long from the dead people and when I got the chance, I was eating.

KALFUS: But as you said, at least, you were eating and it was…But I mean as a …in the hospital then you were probably for many prisoners, the link to survival.

SCHEINBRUM: That’s right. If you stay away, if you got the chance to stay away from the roll call. With the roll call sometimes you had to stand for twelve and fourteen hours.

KALFUS: 12 and 14 hours? Oh my.

SCHEINBRUM: yeah, with no food.

KALFUS: What was the significance of the roll call? Just to make sure…?

SCHEINBRUM: Only to count how many people are missing. If somebody is missing, they have to stay until they find the guy. Maybe they find him dead, drowned in the latrine, you know, or some other place.

KALFUS: So you never had to, or rarely had to stand roll call then, or…?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no. I was in a …behind the ladder, saving a lot of time and helping.

KALFUS: Alright. So you were also inside and didn’t have to do any kind of work?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. But the first two year, I got the bad times too. I was on a big wagon where we had to pull the wagon with big pieces of trees, you know.

KALFUS: So you worked on the outside?

SCHEINBRUM: In the quarry, the salt quarry and all that. But then in ’39 or sometime, we got typhus in the camp and they closed up the camp. And a friend of mine who is still alive in Vienna now, he asked me if I want to help out to be the stretcher bearer, they got so many dead people. I said, “Okay.” I didn’t know that if you were a stretcher bearer, you got this special mark in your files, that you don’t come out anymore.

KALFUS: You don’t come out, because….?

SCHEINBRUM: You know too much.

KALFUS: But while you are the stretcher bearer, you have it better than the others?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. You don’t have to go to roll call, you know. You have to pick up some people who got shot. You have to pick them up outside, a kilometer or 2 miles away from camp someplace.

KALFUS: When did you find out that that was the significance of being a stretcher bearer?

SCHEINBRUM: I didn’t know this until, maybe for 3 years, until I catch myself blood poison, and they released me from the job, and after then they put me as a main nurse in the hospital.

KALFUS: So why didn’t they kill you then?

SCHEINBRUM: See, that’s where the Doctor help me, the SS man helped me.

KALFUS: What was his name?

SCHEINBRUM: Hoven, Hoven. He got hanged too.

KALFUS: Hoven?

SCHEINBRUM: Hoven- H-O-V-E-N. He was from Germany.

KALFUS: How did he help you then?

SCHEINBRUM: No, he put me down…he put me in the hospital. He said that I’m so sick that I can’t….

KALFUS: Did he do that out of humanitarianism?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, I think so. And another thing, he know that I worked in the jewelry business and he wanted me to work for him illegally on the side.

KALFUS: So it was a ….

SCHEINBRUM: He pulled out the gold teeth from the people, from the dead ones. And now he gives me this order that I should do something for him. And I tried and tried for months. I told him I needed special tools and things.

KALFUS: You didn’t have your tools, of course, with you.

SCHEINBRUM: No, nothing, nothing. He said, “Go over in the tool shed over there and ask for them.” But anyway, after 6 months, I think he got tired of me and let me go.

KALFUS: How did he get them? Someone else made them for him?

SCHEINBRUM: From a dental station. A polish boy made them.

KALFUS: It’s interesting that you, Ludwig, you say in one way he did it out of humanitarian reasons, and on the other hand he needed you, eh wanted to use you also. So it was a combination.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, but then the last transport was going to Auschwitz. I think it was ’43 and all the Jews had to go. And I asked him, I say, after he got the title, Hauptsturmfuehrer, “What do you think, should I go?”

KALFUS: You asked him that?

SCHEINBRUM: I asked him. He said, “Don’t go. So long I be here in charge at the hospital, I can help you. But if you go in another camp, I can do nothing.”

KALFUS: So he actually managed to keep you in Buchenwald?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah.

KALFUS: Was Buchenwald…Buchenwald had a crematorium?

SCHEINBRUM: Oh yeah.

KALFUS: But not a ….

SCHEINBRUM: Gas chamber. No, no.

KALFUS: Not a gas chamber?

SCHEINBRUM: No, but outside the horse stable, they got a shooting place where the Russian soldiers…they killed 8,000 Russian soldiers on the outside. I don’t know if you know the story. They brought in Russian officers and other people and they put them under a slot to measure the height. Behind the slot, an SS man shot them.

KALFUS: So that they knew exactly where to shoot them. But hose were the Russians. But the others, the prisoners like yourself there, they died by basically, from overwork, mal-nutrition, not enough to eat?

SCHEINBRUM: Overwork. Not enough to eat. They got only 800 calories a day. I managed maybe when I eat twice as much the calories didn’t count. When I eat twice as much as 800, it’s not 1600. It’s still the same, but that’s the reason I looked good on the picture, you know.

KALFUS: (LAUGHTER) Right, right. But you had mentioned the Russian soldiers. Was there a hierarchy with in the camp as far as the political prisoners and then the Jews?

SCHEINBRUM: At first, in the beginning. When I was coming into the camp in ’39, the criminal prisoners had the power in the camp. After them, they changed, they made so much bad things, you know. They were stealing the money from the prisoners and everything else. Finally the SS said, “No we don’t give it to the criminals anymore,” and they put political prisoners in charge. And in charge was communists. Communists and Socialists. And that’s where they found out that I had got a little political background and maybe was the reason I got better than the other ones, too.

KALFUS: So that being a Jew was one of the lowest levels.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. If you be a political Jew, you had it better than a regular Jew.

KALFUS: That’s amazing. What about…I don’t know if that was the case in Buchenwald, with homosexuals.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah. They got their own sign. They got the pink triangle, you know, the pink on yellow…no, pink on red.

KALFUS: Uh huh. They were the lowest.

SCHEINBRUM: I got books here, different books here. I’ve got so many books, I don’t know what to do with them.

KALFUS: Do you still read a lot about the period?

SCHEINBRUM: No. Why should I read it? I know what’s going on, you know. When I was…each year, every year, they got a meeting in Germany, the ex-prisoners. There weren’t too much left…the Political prisoners. And I was this year in Wiesbaden, by Wiesbaden and there were only 35 left. I was mention something of the …they cut me down right away. I shouldn’t talk about this, you know. I want to say something but it’s better this way. (TAPE TURNED OFF)

KALFUS: What was the…you mentioned the organization in Germany, is that now the group that you met in Wiesbaden…is that the political group that you belonged to before the war?

SCHEINBRUM: They say that it’s un-political, but that’s all it was a concentration camp.

KALFUS: Former inmates of Buchenwald?

SCHEINBRUM: Buchenwald and other little camps, you know.

KALFUS: Around Buchenwald then.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah. We furnished from Buchenwald to send the prisoners to other factories, to other camps. Like where they made the V-1, you know, the bomb, V-1, V-2, which hurt the people, you know.

KALFUS: In other words, some prisoners worked on those in the factory?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. Underground in mountains and they never come out. They sleep inside, the work inside and only come out when there were about 35 dead people a day coming in the night with the truck and we had to take them off.

KALFUS: I mean, that was part of your job then, taking the dead from the…

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah.

KALFUS: How do you keep an attitude of…? You don’t know it today?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no, that’s a business. You get so that you don’t care.

Tape 1 - Side 2 (Kalfus)

KALFUS: For me it’s just fascinating listening to you talk. I mean, I grew up in a rather sheltered environment, although my own, my grandparents were killed in Gurs, in Southern France, in Poe.

SCHEINBRUM: During the war?

KALFUS: Yeah.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah.

KALFUS: So to hear, you know, I always ask myself, “How does one survive?” Can you see that so much death…and (INTERUPTION – BELL RINGS – TAPE OFF). What I started to say was, you know, was to put myself in your shoes and taking on dead body after another, I ask myself, “Could I have survived that?” And you say…you remind me somewhat of my father…you have a very, I think, a really positive outlook on life and I think you’re probably – correct me if I’m wrong – in spite of everything you experienced, you’re on optimist…

SCHEINBRUM: What I can’t change myself, so what’s the use to talk about it or worry about it.

KALFUS: But while you were, so you said that after a while, taking one dead body, it…you sort of become immune to that experience.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah, sure.

KALFUS: So that, I mean, I would imagine one is so concerned about surviving oneself, that… that becomes the primary goal and everything else becomes somewhat secondary. Did you, what about the contacts, the friendships within camp? Was that not important?

SCHEINBRUM: It’s very important. If you be a loner, you can’t survive.

KALFUS: I’ve heard that a lot.

SCHEINBRUM: You have to have friends. You have to help somebody, to help you in case… you needed help.

KALFUS: So it’s kind of the community of misery and…

SCHEINBRUM: Right. (LAUGHTER) I got a chance…somebody got a dog, Schuler, Ding and I don’t know…we decide _________, he don’t need the dog. We want to eat it. I ate a dog. Somebody killed it so we eat it. I don’t care, I eat a dog. It tastes good, you know. One day it was a dog. The next day it was a cat. We didn’t care what it is.

KALFUS: Right. But it was important that you cared about other people and that you shared the…the misery as well as the …whenever you had a chance of…

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, oh yeah. You see the French people; the French prisoners got a chance to get packages from France, friends from Denmark.

KALFUS: All through the war?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah Red Cross packages. And I got…one day they brought in a group of Danish police officers what refused to shoot on the Danish railroad workers what didn’t want to unload weapons for the Germans. And the Germans told the Danish police to shoot on them, and they refused. They took the whole police force of 1500 men and they marked them for the trucks in the camp, as prisoners. But they didn’t have to work. They got honor. They…

KALFUS: They were treated….

SCHEINBRUM: They got barbed wire around their own building. I got in touch with one guy, and I’m still writing to one in Copenhagen and he helped me a little bit. You know, they got packages and he give me a little piece sausage, a little piece bread or something, you know.

KALFUS: I mean you still have contact with a lot of…

SCHEINBRUM: Oh yes.

KALFUS: ….all over the world it strikes me.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yea, in Spain, Denmark.

KALFUS: These are former prisoners?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. One in the United States, a pilot. We got, one time, they brought in about 180 pilots that were shot down over Germany. But they was not…they got no uniform. They got… how you call it, like blue jeans in one piece. And they didn’t count them as prisoners.

KALFUS: Weren’t you envious of those, the preferential treatment, for example, that the Danes got?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, but you can’t do anything. What you want to do? You try to help them a little bit, something. I got in touch with one, with one pilot. He’s still in San Francisco. I’ve got his address. And he couldn’t talk, only a few words – German. I helped him. I brought him some shirts and other things what I got the chance to steal from dead people, you know.

KALFUS: Right. Have you visited some of these people then?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, there was about 66 of us at the end, but we don’t keep in touch anymore, no. They work and they write one time a year. The other people…I got a doctor from the camp who is in Chicago, Dr. Heller, from Czechoslovakia, they are good friends together. And they got some people in Germany, and one is in Holland, in the Hague. And, Spain. There is one in Denmark, you know, and then also I have a few I’ve been writing.

KALFUS: But I really find that so important to hear that, that one forgets that, you know. You think that survival is the…”I’m ‘number one’ and I’ve got to survive,” but somehow you can’t do it without caring about other people, somehow….

SCHEINBRUM: No, yeah. I tried to help as much as possible, you know, but sometimes I couldn’t do anything, you know. One thing I remember, one guy from Berlin, he asked me if I can help. Then I say, when I can help you, it’s okay, but I don’t know how come they brought him in to the hospital and he had to get killed. And he told me in front of the SS doctor, Hoven, what gave him the shot, he said “Ludwig, you promised me you would help me.” I tried.

KALFUS: How do you feel when somebody says that to you?

SCHEINBRUM: Pretty lousy.

KALFUS: Yeah. But you know, you hear so much about and there’s probably….you find the use of these terms rather, rather foolish when you live it. But I remember – I don’t know if you saw the movie, “Kitty Returned to Auschwitz?”

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah, I saw this.

KALFUS: It’s a British girl. For me it’s a wonderful movie.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. (names something) I got this whole thing recorded on tape.

KALFUS: She mentions a similar incident where she was forced to take care of, or she nursed friends in the hospital and then she was the one that was forced to put them on a truck where they eventually were killed, She wanted to die herself. The feeling of guilt, although she had not, as you said, she couldn’t do anything. But did that ever, did you ever feel that way?

SCHEINBRUM: No. I tried to help, but when I saw I couldn’t help, what was the use. I couldn’t do it.

KALFUS: But it’s amazing that same doctor, why did the doctor give him the shot? It was a…it was a poison. He got the order to kill him.

SCHEINBRUM: Every day, 36 in a room, 36 beds. I was a nurse in this. I got the room with 36 beds, every day.

KALFUS: How many were killed? How many?

SCHEINBRUM: Every day, thirty-six.

KALFUS: So it wasn’t a hospital? (INTERRUPTION – BELL RINGS)…Getting back to that. You had to…what was your function actually? All 36 were killed every day and you had to take care of them until….?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. And when they was dead, I had to wait evenings. After then I came to be a stretcher bearer. The reason I got blood poisoning for 8 months, I got over 36 allover cuts, you know.

KALFUS: How long did you have to… you were 3 years in the hospital though?

SCHEINBRUM: Working…

KALFUS: Right.

SCHEINBRUM: 4 years.

KALFUS: But, and basically that was the procedure…that 36 went to the room one day and the next day they….?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, and the next day fill it up again. At night, they took them out. In the morning they brought in another 36.

KALFUS: What did they tell the… the patients, what kind of shot they were getting?

SCHEINBRUM: No, nothing.

KALFUS: They just, they thought they were being cured?

SCHEINBRUM: That’s right. I know what’s happening, but now, how do you tell people what’s going on?

KALFUS: It’s amazing you maintained your sanity in…

SCHEINBRUM: After then, I see, after 6 months, 7 months, I asked Dr. Hoven…”Please take me out of here, I can’t take it anymore.

KALFUS: So you did that particular thing for just 6 months?

SCHEINBRUM: Six months, yeah. After then, they put me in the big room for T.B. There was about 120 beds, it was a life saver, and it was easy for me. But when I come in, I got 2 students, a French student and Dutch student, young boys. They got no medicine, nothing, only got a Polish doctor to help me you know. But then they took the pulse and the fever, a second, and I say, “Wait a minute, hey, you make one minute…not in 2 seconds.” They lie on the cot already. They didn’t like this. I made them work, you know, they got it easy after. They got mad at me , these 2 students, you know. But I …I was very…I got …I was about a year in this… (INTERRUPTION – BELL RINGS)

KALFUS: So we were talking….your working in the T.B. detail.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, I got a lot of dead people every day. I got no medicine for the people. They give me little tablets. I don’t know what it was, aspirin or something. And they think this helped.

But after then, the liberation, General Patton was coming, and the G.I’s coming into the camp in my block. When they saw the guys, oh, they gave them cigarettes, and taste, and things and they started smoking and the next day, I got twenty people dead. That didn’t help them either. Now what can I say. I tell something to the G.I’s – they killed them. (NERVOUS LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: That’s the ultimate irony then. They’re ready to get liberated and then they die. That’s amazing. Did you have written communication with anybody outside, your family, during …during your period in Buchenwald?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, I got the letter smuggled out in German in 1944 by two SS men…that’s the guy, Wilhelm, that got killed. He didn’t know.

KALFUS: Which one? That’s not the Nazi doctor?

SCHEINBRUM: Not the doctor, the other one. The SS man, the one who didn’t do anything.

KALFUS: Oh, this is the one that was…

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, Wilhelm. He was, the prisoner killed him- execution, yeah.

KALFUS: What happened to Hoven?

SCHEINBRUM: Hoven, he got hanged too.

KALFUS: But rightly so.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah. Trial and after the war in Salzburg, I saw a newsreel and I saw the trial. I was bribing the operator from the movie theater to cut out a piece from the prison and I got a print.

KALFUS: Did you really?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah.

KALFUS: But you said about the letter, that was the only communication that you had with your…?

SCHEINBRUM: No, we wrote letters one times a month. But you couldn’t, you couldn’t write. Oh, I got letters here…Red Cross letters. They need one year from me, no. My brother wrote in camp – They need one year.

KALFUS: It took 1 year?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. And then I wrote three lines on the same and that’s another year. So, what good is that? (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: That’s no communication, right. But you knew that your parents and your brother were safe?

SCHEINBRUM: I know they was. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

KALFUS: Did they give you any kind of support?

SCHEINBRUM: Umm, no. I was living from one day to the other, that’s…I supposed them, my parents, saying, “You stay healthy,” that’s all…”maybe we’ll see each other.”

KALFUS: But that was….?

SCHEINBRUM: What can you do when you be inside? You can’t write what you want to do. They got the censorship, you know. They don’t like something, they cut it out. You get beating too, maybe.

KALFUS: Right, right.

SCHEINBRUM: I smuggled out one letter and…

KALFUS: When you say “smuggled”, in other words, something you wrote with real…how you felt, or …?

SCHEINBRUM: No, No. A friend of mine, he got hanged in 1934 by political, by the Socialist Party, and we know that he was dead. I wrote a letter to my cousin in Vienna, that it be possible that I join the guy, and they know he’s dead, you know.

KALFUS: You said that …you join him. In other words, that your life is also….?

SCHEINBRUM: In case you find out that I have to go to the war, you know, I wrote a letter. A friend of mine wrote a letter, printed, you know. I signed only my initial “L”. If somebody get a letter that nobody know who it is. And they got the… and I wrote in the letter to send the letter from my cousin to the United States to my parents. And she said, after the war, I found out she said…” You’re crazy. I didn’t want to send that letter to your parents. They would die if they could find out what you wrote.” (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: Why did you write it?

SCHEINBRUM: To let them know in case she got notice that I be dead….

KALFUS: That you’re alive?

SCHEINBRUM: No, that I be dead.

KALFUS: Oh okay. Oh, I understand now.

SCHEINBRUM: That I joined, somebody killed me, SS or something, that’s she’s not surprised.

KALFUS: I can understand that she didn’t send the letter off to your parents.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: How many years did your parents live in the United States?

SCHEINBRUM: They died in ’48, ’49.

KALFUS: They are buried?

SCHEINBRUM: In the refugee cemetery on Olive Street.

KALFUS: So just a…you were with them a few years after….?

SCHEINBRUM: One and a half years.

KALFUS: 1 & ½ years?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah.

KALFUS: You had mentioned…where did your parents send…let me backtrack for a second. What do you remember of the liberation of the camp? You started to mention that.

SCHEINBRUM: Oh my gosh. The liberation, you see, they took away 40,000 people in the last few, in the last week from the camp. Marched them away.

KALFUS: Where did they march them?

SCHEINBRUM: They killed them most on the road. They couldn’t march, some ran away.

KALFUS: I also know that prisoners from Auschwitz, weren’t they marched to Buchenwald also?

SCHEINBRUM: That’s right, that’s right.

KALFUS: And what happened to them in Buchenwald?

SCHEINBRUM: They come the last few days, but they, the next day, they marched away again. They got no place, no food, no nothing. They dead people was piling up. We didn’t know what to do with the people, you know, I remember 3 days before the liberation, Hoven, the SS man, the big shot, come down in the hospital with the Red Cross with a machine gun around, that already, they keep together a Red Cross, with a machine gun around.

KALFUS: Right exactly. In other words, he was covering his ass.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. And we have to stay in line, all the employees from the hospital, and he hold a speech. He said, “Now we don’t know what’s going on the next few days.” And we got about 3 or 4 doctors, French doctors, that belonged to the International Convention, Genfer Convention…

KALFUS: Geneva Convention.

SCHEINBRUM: ….as prisoners. And they suggested that we meet the commandant from the camp to ask him that if the American Army is coming, if the prisoners give out word that the SS men what were still in the camp, nothing would happen to them.

KALFUS: But they didn’t do anything.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. And it was then last minute and they gave no reply. The commandant gave orders to the next airport to bomb the camp. And the airport, the next German airport, was a German soldier, not an SS man, and he refused to do it. Now, anyway, after the speech from Dr. Hoven, I walked home, back to my…my block and he was coming with his jeep behind me and he stopped and said, “Now Ludwig,” he said, he called me Ludwig. He asked me, “What we do now?” He asked me. (TEARFUL) I say, “Dr. Hoven, I don’t know what you’re doing, but I’m 7 years in the camp and now I should end up the last day, and I don’t know what to do myself.”

KALFUS: Suddenly the person who is in charge is no longer in charge.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah.

KALFUS: So he was scared.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. The day after then, General Patton was there, they catch him about a mile away outside the camp.

KALFUS: Did you see General Patton when he came in?

SCHEINBRUM: No, he didn’t come in.

KALFUS: He didn’t come to the camp?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no, no. But I know it was 2:30, noon, when the first tanks was coming out of the woods.

KALFUS: What kind of a feeling was it?

SCHEINBRUM: Oh my, oh my.

KALFUS: It must be amazing.

SCHEINBRUM: Funny, funny.

KALFUS: After 7 years, I mean, that’s an unbelievably long time.

SCHEINBRUM: After 2, 3 hours, the door was open, you know. We broke the electric wire. The SS were on their way on bicycles and left everything. All of the people that was able to go, we got only 21,000 left and the most are sick people. And they was gone, the SS, the occupation, and they grabbed grenades and guns and machine guns. Everything they got the chance to grab, they took this from the camp. You never know, maybe the Germans come back again.

KALFUS: That’s interesting. So, you…you…you, somehow still didn’t believe it?

SCHEINBRUM: But the one thing, see that’s what the, the Communist blamed the DPB freed the camp on the inside, is not true.

KALFUS: I’m confused. I mean, Buchenwald was liberated by the Americans.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, but the, the Party, the Communist Party in the camp said we liberated us alone.

KALFUS: The political prisoners?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. I saw them in Wiesbaden again. I couldn’t say anything. When I say anything, they cut me down. These are the books I got from Germany, didn’t mention anything, only one book.

KALFUS: So within the camp there was a very strong Communist organization?

SCHEINBRUM: Oh yes, yes, yes. Ninety percent.

KALFUS: But when you say…talking about 90% of the political prisoners?

SCHEINBRUM: 90% were Socialists and you got some Catholics too.

KALFUS: But not the Jews?

SCHEINBRUM: No Jewish were involved.

KALFUS: Okay. So you’re talking about the political…

SCHEINBRUM: Only one political Jew. He’s a big shot now in Westfalen, in West Germany. He is writing. I got the papers every month from Germany, you know, in German print.

KALFUS: He’s in West Berlin?

SCHEINBRUM: West Germany.

KALFUS: West Germany.

SCHEINBRUM: In Ebensberg, that’s Buchenwald, the barracks of Ebensberg. I get this from Buchenwald. I get this letter every 2 months, all the people that was in the camp.

KALFUS: But, I, you know, to see yourself be liberated and then grab weapons thinking, “Well we, sure is sure,” you know.

SCHEINBRUM: You never know.

KALFUS: Just in case. I mean, after 7 years, it’s not surprising.

SCHEINBRUM: No. When I was going out of the camp one time, 3 German airplanes was coming very low. And I think they were going to start bombing the camp. But the U.S. Army got already flaks, you know, the…and they were shooting like crazy. I was laying in the ground, in a ditch, and I didn’t move my head because you never know what’s happening. About 2 hours later, a big tank came down, about 10 feet long, and a parachute. In it was, a thing inside, papers written in 4 languages for the prisoners, you know. And the tank popped open when it hit the ground and opened up, you know. It was metal or – I don’t know- but newspaper print for the prisoners. They didn’t know I was free, my gosh, they were not going to bomb on us, but they were throwing, it was a big bomb on the camp. It was on Friday at 12:30. There were about three and a half thousand airplanes that was bombing the camp.

KALFUS: What kind of feeling was that?

SCHEINBRUM: Ah!

KALFUS: Was that worse then every day?

SCHEINBRUM: No. Every day they got shouting going, we have to turn off the light, you know…turn off the light automatically, you know, for years.

KALFUS: You mean you knew it was the Allies that were bombing and yet you could have been killed just as easily?

SCHEINBRUM: Sure, sure, sure. One bomb came, hit the camp and 5 or 6 people got killed. The other ones, most if us outside was big factories, work factories. They hit all the factories, they leveled everything, it was nice to look and when you see everything burning, you, know. You got a funny feeling, you know. (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: Oh, it probably was. I mean, the feeling of finally being able to….

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, one thing, they destroyed all the files from the prisoners. About 80,000 prisoner files were burned.

KALFUS: The SS destroyed them?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no. The bombs destroyed them. The whole building where they got the files was burning. And after then the SS had to make new files. But a few hundred left disappeared, and nobody know how many was going, what was left of it from the camp. But where are you going? You got no..no food. If you go to somebody, they call the police on you. It was no use.

KALFUS: Right. I mean, escaping was….

SCHEINBRUM: No, no. Three guys escaped from the camp; they got them. They got everyone, they got them and hanged them in camp, and we had to watch on. The days we had to stand and watch them, the brothers being hung.

KALFUS: Watch them? Their bodies hang?

SCHEINBRUM: Hanging all day long.

KALFUS: As a reminder of not to do…not to….

SCHEINBRUM: Then you see, when you see things like this, you see people killed, you see people beat up, you look on it. It don’t bother you no more. Like if you don’t get beat up, it’s alright.

KALFUS: And afterwards when…I mean, you don’t..you know, what’s the word I’m looking for? Was there any kind of..immediately after you were liberated, was there any kind of desire for revenge?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no. To who, who? There was nobody there. The poor SS man. Ninety percent were forced to do it anyway.

KALFUS: But somebody like..like Hoven, for example. He wasn’t forced to do it.

SCHEINBRUM: No. I don’t know any case where he asked me and another friend – he died last year in Germany- to kill another prisoner in front of him. Now how you tell him you can’t do it?

KALFUS: So you had to do it?

SCHEINBRUM: No. I didn’t do it. He showed me how to do it.

KALFUS: So he killed him?

SCHEINBRUM: Then after the man, he was dead, he said, “Now look, you can take the shirt, I’ll take the boots.”

KALFUS: Hoven said that?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah. And he got these nice music accordions, harmonicas.

KALFUS: Harmonicas?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, he took this, you know. “You keep the shirt.”

KALFUS: I mean…but that’s an example of not an innocent SS officer.

SCHEINBRUM: No, no, no. He was…he was…

KALFUS: He knew what he was doing.

SCHEINBRUM: He got the order to kill him but a way like this. The guy could have gone the next day to another camp. He was a crook, I know. He was a foreman for other prisoners. And they beat up the prisoners and they stole their money…their food and everything else. Now he got paid, that’s the reason Hoven said, “You kill him.”

KALFUS: Was he a Kapo, or….?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, a Kapo. And I had to pay him off to get out from the …from the quarry, from working.

KALFUS: You had to pay, the…the….?

SCHEINBRUM: The guy who got killed.

KALFUS: But still you wouldn’t want to kill him.

SCHEINBRUM: No, no. I was standing in the corner and I tell you, I was shaking. He took out the chair, a leg, and hit him over the head, and kicked and kicked him.

KALFUS: So there was definite sadism in his action

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah ,yeah.

KALFUS: I mean, it wasn’t somebody who had to do it.

SCHEINBRUM: And when I got the blood poison. I got the boils, I don’t know if you know boils.

KALFUS: I know what you mean.

SCHEINBRUM: These was growing inside, not outside. I got the blood poisoning from the dead people. I didn’t have the chance to wash my hands. One day I got a boil here.

KALFUS: On your neck, you Adam’s apple?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. And Hoven said, “Ludwig, I, I get this. I operate on you.”The other prisoners was standing all_______________ (LAUGHTER) There were other prisoners there, you know, and he gave me gas.

KALFUS: He did operate…

SCHEINBRUM: He did.

KALFUS: …and saved your life?

SCHEINBRUM: That he did.

KALFUS: The same person that, that took the leg off…?

SCHEINBRUM: …and turned around and killed 10 other people.

KALFUS: I mean, it’s no wonder that you, you’ve…I mean, to survive under those conditions, you know, and, and…

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. And maybe I…I was friendly to everybody, you know, and I tried to help where I got the chance and somebody helped me too, you know. But sometimes you had to stop. You couldn’t help anymore.

KALFUS: But here, he could have just as easily killed you with a…while you were under gas and said forget about it.

SCHEINBRUM: No, another man- I forgot the name – I have to look this up, everything. You know, I’m getting…after 40 years, I forgot some special names, you know. (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: What you remember is amazing. So I wouldn’t….

SCHEINBRUM: No, I was in one room where they killed about 36 or 38. It was a smaller room. And one guy come in, you see, they brought him in. They had a glass door. The SS man asked him, “What you are?” He said, “I was an officer in the Austrian Army in the First World War.” And he said, “What are you doing here?” The prisoner said, “I don’t know.” And he said, “Get out of here.” I said to him, “Kill him. You tell him get out?” That was the one guy I remember he didn’t do nothing to him.

KALFUS: Somebody that probably really liked to play God.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. The other man was about 50 or 55 years old. No, he died in’65 I was back again the first time in Munich.

KALFUS: Who died now? The guy that, that….?

SCHEINBRUM: The killer. He died in Egypt under Nasser.

KALFUS: What? Now I’m confused. Who are you talking about now?

SCHEINBRUM: The second guy, not Hoven. No, no. It was another guy. And after he got 3 years in jail after the war, he opened up his office in Munich for 10 years, he got his office open in Munich.

KALFUS: As what?

SCHEINBRUM: As a doctor. Can you figure this out? And finally when I was over there in ’58, they asked me if I wanted to be a witness against him. I said “Okay.” Now I was going to Dachau to the trial, and they showed me pictures with numbers and all. I said, “That’s him.” And after that, they let him out. Oh, later, 3 years later, they let him go. And after then, somebody from the police told him, “The police are looking for you, the German police,” and he disappeared overnight.

KALFUS: He went to Egypt then?

SCHEINBRUM: He went to Egypt and Nasser put him in charge. And he died about 6, 7 years ago of cancer.

KALFUS: In other words, you were going to testify for…?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah.

KALFUS: I was going to ask you, did you testify on any trial or…?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And against Ilse Koch, too. Remember the name? With the skin and with the shrunken heads? With the skin and the heads?

KALFUS: Now where…in what camp was she?

SCHEINBRUM: It was in Buchenwald. She was the, the, the…

Tape 2 - Side 1 (Kalfus)

KALFUS: You were at her trial then or testifies against…?

SCHEINBRUM: I testified against her, yeah.

KALFUS: What happened to her?

SCHEINBRUM: Well she got life for the ..for the…from the other camp court and after 3 years, they let her go. The other camp insists she didn’t do anything against the other camps. She was doing something against the Germans.

KALFUS: What did she do with the shrunken heads? What was the….?

SCHEINBRUM: She got lamp shades and books, you know, skin, you know. When she was released, the Germans arrested her again and they put her again on life.

KALFUS: The Germans?

SCHEINBRUM: The Germans, yeah. You know, and after a year she got a baby in jail. I don’t know how she got it. It saved her life, maybe. Anyway, she died in prison and her sister got the baby.

KALFUS: Where was the trial held?

SCHEINBRUM: In Buchenwald.

KALFUS: Were you flown then to …?

SCHEINBRUM: No, I was on the way to the United States.

KALFUS: What year was that?

SCHEINBRUM: ’46.

KALFUS: Oh, ’46 when the trial was.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, ’46. And when I was in Dachau in Muenchen in the camp to go to the United States, I saw in the paper that the trial is in 3 or 4 days. You know, I was going on the train to Dachau and they put me right away on the stand. It was a funny feeling too. You never was a main witness for something?

KALFUS: Never, never.

SCHEINBRUM: You got a thousand people around you and you’re sitting on the podium on a big chair. You had to talk. I couldn’t talk. I got a dry mouth. And they translated in English, you know. I got a German translator, you know. I got 3, 4 guys what I know.

KALFUS: But you were…you….didn’t this hold you up from coming to the United States?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no, no.

KALFUS: I mean, it was…how many…you stayed one day?

SCHEINBRUM: One day, one day, yeah, no. About 2 hours maybe.

KALFUS: But you were willing to be a witness.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, but that’s the thing. When I was here in the United States in ’48, they made the trial for Ilse Koch, the second trial.

KALFUS: What year? ’48 or ’58?

SCHEINBRUM: ’48. And I got a letter from a lawyer, from people that know I know about the whole business. Now the F.B.I. got in contact with me and told me, “You want to testify?” And I said, “Sure.” They brought me to New York with the plane.

KALFUS: So they paid for all of that?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, but her lawyer was here, you know….her lawyer, They asked me questions – “What date was it?” and “What time was it when you saw?” After 4 or 5 years, what did I know what the day? I got no watch. Forget about it.

KALFUS: What happened to her?

SCHEINBRUM: Nothing. That’s all she got really, you know. But the Germans picked her up again. Now how a lawyer can ask you after 3 or 4 years, what time or what date it was?

KALFUS: Yeah, yeah.

SCHEINBRUM: Crazy, I don’t know. When I got sick on the airplane, too. (SIGHS) I didn’t know, I was never flying. I was coming here from Europe to the United States, 11 days on a boat, eleven days….I was 9 days seasick. On the flight to New York, I was 2 hours airsick. That wasn’t too much fun for me either.

KALFUS: Was that, you were already in the States for a while when the trial took..when you were in New York?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

KALFUS: What was the first thing you did when you got out of camp? Do you remember that?

SCHEINBRUM: I remember. I took a blanket and walked out of the open door in woods, and lay down and read a book, alone.

KALFUS: Just to be by yourself for once in 7 years.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, quiet, yeah.

KALFUS: Amazing. You don’t remember what book you read?

SCHEINBRUM: No, I don’t know, I don’t know. After then, I remember I walked to the next town to Weimar. It was only 10 or 8 kilometers away. I walked down the streets and this time the Germans didn’t yet…couldn’t left the house. They had to stay inside. I walked the streets alone, you know. _speaks quietly

KALFUS: As if nothing, people, the same people knew what was going on.

SCHEINBRUM: Maybe they didn’t know. I don’t think they know.

KALFUS: Do you really think that the people that were…?

SCHEINBRUM: Ninety percent was afraid to know about it.

KALFUS: Yeah, but that’s something different, isn’t it, than knowing? I mean, they suspected and didn’t want to know more.

SCHEINBRUM: That’s right. But when I found out, around the camp, about a mile or a kilometer from the camp away were big signs, “If You Go Farther, You Get Shot.”

KALFUS: But didn’t they smell the burning bodies? I mean…

SCHEINBRUM: No, no, no, not there. You know, Buchenwald was on a hill, on top of a hill, and the next town was below, 7-10 kilometers.

KALFUS: You really, you really think that 90%…that’s one of the things that students ask me a lot, you know. And the question is, “How could people not know about what was going on?”

SCHEINBRUM: They were afraid to ask questions, you know.

KALFUS: Yeah, that’s probably put very well.

SCHEINBRUM: They was asking questions, but they say, “Don’t ask too much, you get into trouble if you know….”

KALFUS: No, if you know the answer, then….

SCHEINBRUM: The same when we got the bombing in ’44. I don’t know if I told you – in the camp, they brought in trucks from the next city, from Weimar, to restore water and electric that was hit from the bombs, you know. And I got my white suit on, I was working in the hospital and my hair was a little bit longer and I was one who didn’t have a star. I was the only white suit, you know. And every truck that was coming and left again, I put some 3 or 4 wounded prisoners in them and told the driver to bring them to the hospital. Our hospital was filled already. And the last truck, I said, “Let’s try it.” I jumped on the truck and they was going to the city, and I delivered 2 guys, but they died on the way down. But now I want to go back in the camp. I have to beg somebody, “Please will you be so kind as to bring me back in the camp?” What am I doing in the city? Nobody to feed me. I was standing there on the marketplace in Weimar and a little boy, a Hitler youth, with the pants, with the black pants, was coming with a gas mask around. I asked him, I give him 2-3 marks that I got, “Can you get me something to eat?” I cry. It was the only way I figured that he would never come back with the money. Then a minute later, he was back with this paper with sauerkraut. (LAUGHTER) I was eating sauerkraut, but how much you can eat? It was in newspaper. He got no paper. Everything there you had to bring your own paper.

KALFUS: Right.

SCHEINBRUM: Finally I got the chance to go in a truck back to camp. There was 2 prisoners and the other ones was 2 or 3 nurses and all the people 50 or 60 years old were to help restore our electric, or something. I was going back in the camp and one nurse, a young girl, 18 years, asked me, “How many people did you kill in the camp?” I said, “Nobody. How come you tell the people is all killers, all murderers?”

KALFUS: This was a German?

SCHEINBRUM: A German girl, yeah.

KALFUS: Who was a nurse?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, a young girl, 18 years old. When I said, “No”, the other guy , he told her, “You shut up your mouth or else, you answer one question more.” But that’s what they was lying….telling her lies. Every word they said was a lie. I think those guys believed it themselves. I was glad I was back in the camp. I got my bed and I got my food again.

KALFUS: How long did you stay there until you were…?

SCHEINBRUM: After the liberation?

KALFUS: Right.

SCHEINBRUM: 4 weeks more.

KALFUS: 4 weeks more?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah.

KALFUS: Theoretically you could have walked off at any time.

SCHEINBRUM: Any time. Free Germans, lot of Germans walked off.

KALFUS: A lot of prisoners?

SCHEINBRUM: Prisoners that was living close by, you know, some stole a little carriage, a little two-wheeler or something and put some stuff in it.

KALFUS: And you stayed?

SCHEINBRUM: I stayed. Well you know the fighting was still on. In Austria, they was still fighting, the war still on.

KALFUS: In what year was the liberation of Buchenwald?

SCHEINBRUM: I think in June. And there was in March, was 2 or 3 months later, was still the fighting going on.

KALFUS: June ‘44

SCHEINBRUM: ’45

KALFUS: June ‘45

SCHEINBRUM: The liberation was in March, March 11th, I think. Oh, April the 20th, April the 20th.

KALFUS: Right, so it would have to be June when Buchenwald was liberated.

SCHEINBRUM: Liberated, yeah, yeah.

KALFUS: Okay – 1945 – May.

SCHEINBRUM: May. No, no, no, before, that’s where I got the paper. Maybe before, it was liberated maybe before May 14.

KALFUS: No, it was before then.

SCHEINBRUM: Until April 1st, right?

KALFUS: Right.

SCHEINBRUM: April 1st, 1945. I get mixed up. (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: Oh, (LAUGHS) don’t worry about it. After the 4 weeks, where did you go then?

SCHEINBRUM: Somebody was going out and was stealing 2 bused from the Germans. And all the Austrians piled in and were going home. All the bridges were blown up, you know. They had to make detours. And they got one G.I. officer along in a jeep to get through the lines, you know. Finally we come to Austria, to Linz. I don’t know if you know.

KALFUS: I know of Linz, but I’ve never been there.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. In this time Austria was split in 4 pieces already. Linz was occupied from Russians and they didn’t let us go. I just couldn’t go home.

KALFUS: Then what?

SCHEINBRUM: 4 guys tried in the night to slip over the border. They got shot. The Russians killed them. The G.I said, “What we do – go back to Salzburg.” Then when we was going back to Salzburg, we got a…we stayed in an air raid shelter in Salzburg, on the main place, on Sunday afternoon at 2:30, a captain comes to me – a little guy, and asked me in real Viennese, “You know me?” “No.” “No?” “We was together in Buchenwald?” He was released from Buchenwald, joined the army, was coming back as an interpreter to Salzburg.

KALFUS: Amazing.

SCHEINBRUM: Now he helped me a lot. He helped me get a job at the C.I.C.

KALFUS: What is the C.I.C?

SCHEINBRUM: That’s Civil Censorship, to read letters, you know.

KALFUS: In Salzburg?

SCHEINBRUM: In Salzburg, yeah. And he got me a room in a little castle up on a hill that belonged to Stefan Zweig. Maybe you know the name?

KALFUS: Sure, of course.

SCHEINBRUM: He left 1936 and he killed himself in Mexico. And the Nazis took over the castle and the G.I. know this and he said, “I’ll get you a room over there.”

KALFUS: It’s a lot better than the…

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, he put on his gun, you know. And I said, “What will you do? Go shooting someone to get me a room?” (LAUGHTER) Anyway, we climbed up 142 steps. Today, I couldn’t do it anymore. I talked to the guy, you know. He was an ex-legal Nazi. You know, he’s got 5 clothing stores still in Salzburg now. And he told him, “I need a room for this man here.” He said, “I don’t have any room” And he said, “You want to go to jail? You find a room.” Anyway, he found a room. His mother got 3 rooms. But he said, “You close up one door and on the other side, you open up and you can come in anytime” And yet the walls in this house, so big walls, and after a while you got nobody what can work, no tools, nothing. You don’t have to go up. In 2 days you be in jail. (LAUGHTER). In 2 days he gets divided, he thinks to himself, he makes a door. I got this little room with a toilet, and that’s when I started working for the American people, you know.

KALFUS: And you stayed then for…?

SCHEINBRUM: Until I left Salzburg.

KALFUS: When did you, you said you asked your parents to send you 2 tickets.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, no, I met my wife – she worked in the telephone in Salzburg, too, to listen to, you know.

KALFUS: She was Austrian?

SCHEINBRUM: She’s from Salzburg, yeah. She was born there. She is much younger than I am, you know.

KALFUS: She’s younger than you are?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah. No, it end up, I’m still stuck with her.

KALFUS: How many years are you married?

SCHEINBRUM: 39 years. And now what can I do? I don’t want to go out now to look for another. (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: She’s not Jewish?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no.

KALFUS: Because I noticed the …I noticed the crucifix.

SCHEINBRUM: No, it doesn’t mean anything. It doesn’t mean anything. It’s only the farm in Austria got the holy corner, and that’s our holy corner. It doesn’t mean anything.

KALFUS: Does she practice?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no, no. See what I got? But she didn’t want to use it. (SEARCHES FOR SOMETHING)

KALFUS: Can I help you?

SCHEINBRUM: No. I put this together, you know, from Israel. (LAUGHTER)

KALFUS: Have you been to Israel?

SCHEINBRUM: No.

KALFUS: So far as religion goes, I know I asked you that when you came to my class…so you don’t practice anything?

SCHEINBRUM: No, no, no. If somebody is over there, ‘He’ couldn’t allow things what’s happened in the last 100 years.

KALFUS: That’s the way that I feel.

SCHEINBRUM: (MUMBLES)…not to kill humans…

KALFUS: And yet, a lot of people who experienced what you did are practicing Jews.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. I remember one case, we got Dutch people there who didn’t work either. One day one guy died from them. And he died in the hospital and I had to pick him up from the hospital and bring him up to the crematorium to be cremated. I made up with the Dutch people that I stop in front of them, behind barbed wire, together, you know. And the whole gang start praying in front of the body while it was covered. I know exactly, I told them at the time when I come by, you know. And they thanked me for giving them the chance to …

KALFUS: And yet for you it was meaningless.

SCHEINBRUM: It didn’t mean anything. Another time, we got two priests in the camp, 2 Catholic priests. They put rocks on it, in front of the…they called it ‘The Building’. They were given shoes, wooden shoes, the clumps, they called it. No socks, no nothing. They got the black clothes in one hand, they got the Bible and the rosary, and they decided to put the box in what the SS had. They walked by for hours, on the rocks and said, ‘Heil Hitler’, and was come by here, and the feet of the 2 guys was one bloody mess. They put both in the hospital. One was a heavy guy, and one day we have to bring him up again in the jail on the stretcher. And the SS man was the biggest killer ever what I know. He’s still alive.

KALFUS: He’s still alive?

SCHEINBRUM: He’s still alive. Why? The last few months they took him in the Army, he lost one leg and one arm, fighting. He got a good pension now. He lives, first place, in a ‘Pension’ or in a hospital. I found out this year. I got a picture of him.

KALFUS: What is his name?

SCHEINBRUM: Sommer, Martin Sommer. I show his picture if you’ve got time. And I had to bring him up on the stretcher back into the hospital and this SS man, Martin Sommer, was behind me. And it was the first time for years where I noticed this guy, Sommer, he got soft. He said, “Set him down and take a rest,” to us. And he walked up to the priest and said, “Du schwein, you swine.” “You be a pig, you ought to be ashamed that 2 Jews had to drag you around” He didn’t say nothing. Now another time, the same guy, this SS man, called us about 2:30 in the morning.

KALFUS: This is Sommer?

SCHEINBRUM: Sommer, yeah. We was asleep and the loudspeaker…He called us, “Stretcher bearer to the door.” And we run up with the stretcher, and he got the gun in one hand and the flash light in the other one. We walked out about 10 minutes in the woods, there was a body, pick him up and bring him into camp. I lift him up and I remember, he got rubber boots. And rubber boots, the Russian soldiers had rubber boots. And the jacket was a Belgium jacket with Belgium buttons on it, the army buttons. He got long hair. It was no prisoner. I don’t know who it was. Anyway, I was going through the door inside the camp to the crematorium and he said, “If you look on the guy, I’ll kill you both.” Now in the morning, it was 6 o’clock or after and I looked at the guy. We didn’t know the guy. You see, I was reporting everything that was happening to the political section in the camp.

KALFUS: To keep a ….?

SCHEINBRUM: To keep a record.

KALFUS: Wasn’t that dangerous?

SCHEINBRUM: Sure it was. But you have to help somebody.

KALFUS: I mean, some of that information then was used to prosecute some of the …some of the Nazis.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. Another thing, one day, I don’t know if I told you, we got the file in the basement with about 50 or 70 files of the dead bodies. And everybody had to get a number, his own number. We got the ink pen, but the ink pen write only when it’s wet. You know what to do, pick up your leg and put the number on the leg. Then finally when they deliver this up to the crematorium from the laying on top of each other, something changed the ‘3’ to ‘8’, or the ‘8’ to ‘3’, I don’t know. Something changed, maybe a ‘1’ to ‘7’ or a ‘7’ to ‘1’. And they got the wrong file. They took out the wrong file from the…they took a file out on a guy what was still living and wanted to burn him up. And they called me, the SS man. He was a mean guy too, he called me up. And when I was coming down to ask what he wanted, another prisoner, Monti Gan, a criminal, and he knew me for years too, he said, “What you doing here?” I said, “The SS man called me.” He said, “You go away, he kill you.” I was disappear. I was gone for 2 weeks, and Hoven helped me too.

KALFUS: What do you mean?

SCHEINBRUM: Hoven, he said, “You stay in bed. You be sick for 2 weeks.” On one side he helped, on the other side, he killed.

KALFUS: Right, right. So you and your wife, did you get married in Austria?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, I got married before.

KALFUS: In Austria?

SCHEINBRUM: 6 months ahead. In May ’46. And I think in May, a year, no….I can look this up. In April we was coming over, a month later.

KALFUS: I think I remember you said you have one daughter?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. She’s married and lives in Blackjack now.

KALFUS: Okay, yeah, right. And those are your grandchildren over there?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, there are 2, they are now 12 and that’s 9.

KALFUS: I wanted to ask you, did you talk to your daughter about your experiences?

SCHEINBRUM: She told me, “Why didn’t you put this in a book?” Who would listen to me?

KALFUS: Oh, I think it’s fascinating, but I think it’s, it’s…

SCHEINBRUM: I tried to, I wrote, I started something. I got this in German. I got this so many times translated in English and I was sending away, sending away to Reader’s Digest. They sent it back to me. They said, “We are not interested in the story.” Now I don’t know if I got something in English again, I don’t think so. That’s the same…that’s all in German. You think you can read them in German?

KALFUS: Oh, I’m sure I can read it in German. But I think it’s …some people want to put that in books. I think it varies from person-to-person.

SCHEINBRUM: Maybe it’s the same here. You can keep this one here.

KALFUS: But with your, I was interested in the fact that you talked freely to your daughter about your experiences.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, a few times.

KALFUS: Or did she ask a lot of questions?

SCHEINBRUM: A few times, but I don’t think she’s too much.

KALFUS: It’s another world for her.

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, she has lived here now and she don’t know anything what was going on.

KALFUS: Does she speak any German?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. She was one year over there in college in Vienna. She talks, not perfect, but she talks.

KALFUS: So you and your wife spoke German at home then, right?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, no. I talk to my wife in German and she talks English to me, you know. Otherwise she forget the German.(LAUGHTER) All is wrong. You know. If you want to take this along.

KALFUS: Well, don’t give me the original.

SCHEINBRUM: If you find somebody that’s …I got this here (shuffles things) Take the original.

KALFUS: No, I won’t take the original.

SCHEINBRUM: No, I got the original here.

KALFUS: You want this back?

SCHEINBRUM: No, keep it. I’ve got the original here.

KALFUS: Okay.

SCHEINBRUM: (SIGHS)

KALFUS: And your grandchildren, do you talk to them at all about this kind of experiences?

SCHEINBRUM: No, I think that’s unnecessary.

KALFUS: At twelve?

SCHEINBRUM: I give them some books to read, but we never got the chance to talk about them, you know.

KALFUS: Did your daughter go to college in St. Louis?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah. I’m looking for a, the first_________about all this…paper. (SEARCHES)

KALFUS: But it’s interesting that you managed to really keep an awful lot of….

SCHEINBRUM: Pictures about the (SEARCHES). I don’t know where I got it saved, from what paper, you know. And that’s a picture from the Post Dispatch in ’47 when I was coming to St. Louis. (CONTINUES SEARCHING)

KALFUS: That’s your wife?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah. (SEARCHES) You know the name, Dr. Eugen Kogon?

KALFUS: No.

SCHEINBRUM: Oh, he wrote this book about the camp in English and in German.

KALFUS: Oh, Kogon, sure, sure.

SCHEINBRUM: Kogon, yeah, yeah. I tried to talk to him, but he’s too busy. And this is Ilse Koch. Here’s another guy, I don’t know. (SEARCHES)

KALFUS: Well that’s really fascinating. Well I may take this then…this?

SCHEINBRUM: Yeah, yeah, you can. This is from the American Red Cross, May 1942 and when it’s come back, 1943 is the date. (LONG PAUSE) My brother….

KALFUS: I can understand. Do you see your brother regularly?

SCHEINBRUM: He was here about 2 months ago. He’s a big shot now in Texas.

KALFUS: What does he do in Texas?

SCHEINBRUM: My gosh, maybe I could give you some piece of paper. (LAUGHTER)

Tape 1 - Side 1 (Epstein)

HEDY: This is Hedy Epstein. I am a member of the Oral History Project of the St. Louis Center for Holocaust Studies. This is November 23rd, 1985 and I am interviewing Ludwig Scheinbrum. This will be the second interview, the first one having been conducted by Richard Kalfus. Mr. Scheinbrum, I read the interview that you had…or I listened to the interview that you had with Mr. Kalfus some time ago.