…for my parents to send me away, but you know, the people in the community saying, “You don’t do that.” And then my coming out with…I’m not your real child.

Eidelman: When you say people in the community, did someone say that to you?

Epstein: No, but I heard people say it to my parents. You know, they’d say, “You’re not really going to do that?”

Eidelman: Jewish people or Christians?

Epstein: Yeah, both. “You’re not really going to let her go. I mean, that’s foolish to do that. It’s not wise, you know. Times are difficult, and you don’t know what will happen and it’s best if you stay together, and…” I didn’t have any understanding at that point of how difficult it must have been for my parents to have just made that decision and to carry it out and then have to deal with all this other stuff that other people were saying…that I was saying. But when they put me on the train, and as that train pulled out of the station, I was looking out of the window, and my…they ran to the end of the platform, and I could see them getting smaller and smaller and smaller, and finally, they were two dots and then they were gone. And the minute that happened, you know, and I’d saw as the train was pulling out of the station the tears they were trying to suppress and the expression on their faces, “My God, those people really love me. That’s why they sent me away.” And I immediately sat down and started to write. And I’m really glad that I did that and they did get that letter. I know they did because they confirmed that they did, and I told them, you know, that I…I apologized and that. I said maybe it was my own hurt that I didn’t understand., but all of a sudden I think I matured. By the time, you know, my parents…I could no longer see them, I think I instantly aged and had a maturity about me that was nowhere near the day before, or an hour before. And then I knew that they did this out of an act of great love and sacrifice, and you know, maybe what they were doing was, you know, saving me from a lot of unpleasant things, and I didn’t know what they were at that time for sure.

Eidelman: At first, you said that they said you didn’t have to go to the school out of the country unless you wanted to.

Epstein: That was in 1936.

Eidelman: I see. And then, how did they—how did they tell you and what was your reaction when they first told you that now you would go?

Epstein: Well, you remember when I was sitting up in that wardrobe with my mother, and I said I want to get out of here—not just out of here, but out of Germany—that was really the beginning, and, you know, that was carried forward, and I knew, you know, that things were in motion, and I was very much aware of what, you know, each step of the way, not this, and now we have to write another letter, we have to do this, we have to do that.

Eidelman: I see.

Epstein: And I did not object. That’s what I wanted. And, I, it was only, you know, as I said, a couple of days before that all of a sudden, and it was probably because, you know, I didn’t even know how to cope with my feelings and how to express them, and I am sure I had some. There was a lot of excitement and new things, you know, I’m going to another country, and I’m going to be speaking English and all this…going to London, to a big city, from little village of a thousand to a big metropolis, so there was a lot of that. But actually, there was a lot of fear and apprehension also. And I didn’t know what those feelings were and so, you know, rather than maybe try to, I didn’t have the wherewithal, I guess, to deal with them and to understand. I blamed my parents for wanting to get rid of me. You know, it wasn’t my fault what I was feeling—that it was their fault. And, but then, I’m glad that I had that insight and that I had it so quickly. I, you know, and I was able to share that with my parents and thank them for what they were doing for me, and that I understood the great pain this must have been for them.

And I became, in fact, very protective of my parents after that because there were some things happening in England that weren’t so good. And I did not share it with them because I felt at this distance they probably could do nothing about it. They’d worry about it, and I didn’t want to contribute to their concerns. So, all was well. I never told them of my problems, except that at some point I had to because there was a change of address because of the problems, and so then they wanted to know why, you know, if all was so well, why did I leave? Because the family I was with—I was placed with a family that…I didn’t know this cousin of my grandfather who sponsored my coming to England contacted a Rabbi and he [the Rabbi], in turn, found a Jewish family, and I was placed with that family. And my grandfather’s cousin paid for my board and lodging there.

But for this family who was, I would say, at least middle class just judging by the house they lived in and their lifestyle, they, I think, it was a money-making proposition for them. You know, the living there, sharing, I mean sharing the bedroom with one of their daughters—I don’t think I cost any more money except washing the sheets, I guess, but the way they saved the money was on food. I was given…I was told that in Germany I was hungry—and I never was hungry in Germany. The only thing that I remember was that butter was rationed, but you could eat well without butter. And that now that I saw that food was plentiful, I needed to start, you know, I wanted everything. But I needed to start slowly, get accustomed to eating, and really what happened was I immediately had to get used to not eating. My diet consisted of a piece of toast and tea for breakfast, and two pieces of toast and tea for lunch, and two pieces of toast and tea for supper. And on Sundays, I got another treat…a treat—I got a cookie in addition to my piece of toast at breakfast. I was afraid, and the only ones I would have wanted to tell were my parents, but I didn’t want to tell because it might worry them. And, but I was afraid to tell anyone else.

Also, there was a language handicap, and I didn’t really know anybody. I didn’t know what the resources were. The cousin of my grandfather went to France for her vacation with her daughter and her family two days or three days after I arrived in London, and they weren’t going to come back until late in the summer, and so I couldn’t tell them, and children, you know, in school. I started school almost immediately; I think I arrived in England on Thursday, and the following Monday I started school. And there were some German or Austrian refugee children in school, but everybody tried to speak English, but they had two days longer in school…two days better. (LAUGHS). And so, and since I was the newest one, you know, I knew nothing or very little. And, also, I was afraid, you know, or ashamed to say how bad things were. And kids would bring candy and cookies to school and offered some to me, but I wouldn’t take any. I was dying to have it because I had never…I would never have anything to give them. The best I could bring was a piece of toast; I knew they wouldn’t want that.

And it was probably almost two months after I got there—got to England and stayed with this family, in fact, this cousin of my grandfather’s and her daughter, and her daughter sort of became a liaison person actually, came back from France—they came back earlier because of the possible threat of war. This was in July when they came back. I remember they called me late in the afternoon and asked me how I’m doing. That was the first time that I spoke up. They said, “How are you?” And I said, “Hungry.” That was uppermost in my mind. That’s all I ever thought of was that I’m hungry. And she said, “Well, when do you eat dinner?” And I guess it was somewhere near 4:30, and I said, “Well, it’s not going to make any difference.” She said, “Why? You don’t like what’s for dinner tonight?” And I said, “No, that’s not it,” and I said, “Well, I just, I can’t talk.” I guess we were talking in English and the woman was, you know, not too far away, and I was afraid to really say anything. So she said, “Well, why don’t you come on Saturday to visit us for lunch and then we’ll talk?” And I said, “I can’t come.” And she said, “What are you doing on Saturday? You want to come the following Saturday?” And I said, “I can’t come then either.” She said, “Well, what’s going on? Why are you so busy? What are you doing?” And I said, “It’s not that I’m so busy, but I don’t have carfare.” And you needed to take the subway to get there. And so she said, “Well, have you spent your allowance already?” And I said, “Allowance?” That’s the first time I knew I was supposed to have an allowance. And so she said, “Is Mrs. Rose there?” That’s the family I lived with. She said, “Let me talk to her.” So I called her to the phone and they had a conversation. Then I was put back on the phone, and she said, “Well, Mrs. Rose is going to give you carfare and you can come to us on Saturday. She will tell you how to go.” Because I had not been on the subway since the day that I arrived and I was picked up, you know, so I really didn’t know how to do that.

And when I got there, I immediately started eating, and I ate all day long. I didn’t stop eating. (LAUGHS). And they said, you know, “It’s there, and you can have it, but you know, you are going to get sick.” And I said, “I don’t care.” (LAUGHS) And, they just really didn’t want to believe at first that things were really so bad, except they could tell. You know, the clothes that I had on were just hanging on me like a bag. I had lost a lot of weight. I was skinny before, but I lost a lot more weight. And they gave me some money so I could buy myself food on the way to school or from school; they asked me to stay there about another two weeks or so since school was going to be out for the summer. They said, “We’re going to try to find another family, and we’ll try and find one where you can continue going back to the same school in the fall, but that may not be possible, so why don’t you at least finish the school year there.” And well, and they said, “We will explain to the family. You don’t have to explain anything. Don’t ask—if they ask questions, you just tell them to talk to us, and you’re going to come and stay with us and that’s all you’re going to tell them.”

Eidelman: Was the family you were staying with Jewish?

Epstein: Yes, and, because the Rabbi found the family. And so I very briefly stayed with the daughter of my grandfather’s cousin, and then she found me another family for me. And I guess they must have been told how hungry I was, and so they couldn’t ever feed me enough. I would say I’ve had enough, I can’t eat anymore, you know. After a while, I realized, you know, I don’t have to eat ahead. And, they were extremely poor, and probably the money that they got really probably helped them in their budget. But I was never short-changed. I think, if anything, they would probably taken something out of their own mouth or out of their own children’s mouth rather than let me go short on something.

And I stayed with them until just before my sixteenth birthday. Because then the cousin of my grandfather told me that “In England you only have to go to school until you’re sixteen, and you’re going to be sixteen next month, and so when school is out in July, you’re going to have to go to work.” And I was just absolutely flabbergasted. Because first of all, I had not finished high school, you know, and I was going to go on to university and this and that, you know, I was going to go to school in France and Switzerland, and all these things came back. And now I’m supposed to go to work? And what, I didn’t have a trade. I don’t know how to do anything. And I hadn’t even thought about what I want to be when I grow up, you know, like this, that, or the other, but I didn’t know if any of those things, you know, would ever be real.

And I just really panicked, and so they helped me find a job. It was a live-in job with a cantor who was either divorced or separated. I don’t know which, but his wife was not in the house, and he had a 14 year old daughter, and I was to be a companion to his daughter. And she was kind of a weird kid. She had no friends, so I was to pick her up at school…take her to school…play with her…dust the house—it was a huge house that they lived in. Really, the job was a nothing job, but it provided me a roof over my head and some food and loads of money, I made so much money that I thought I was well on my way to being a millionaire, but I wasn’t. But to me it seemed like a lot of money all of a sudden because I had, you know, no needs. Everything was taken care of; I mean, even if I needed toothpaste, they bought that for me. You know, it was all mine to spend, to save, whichever.

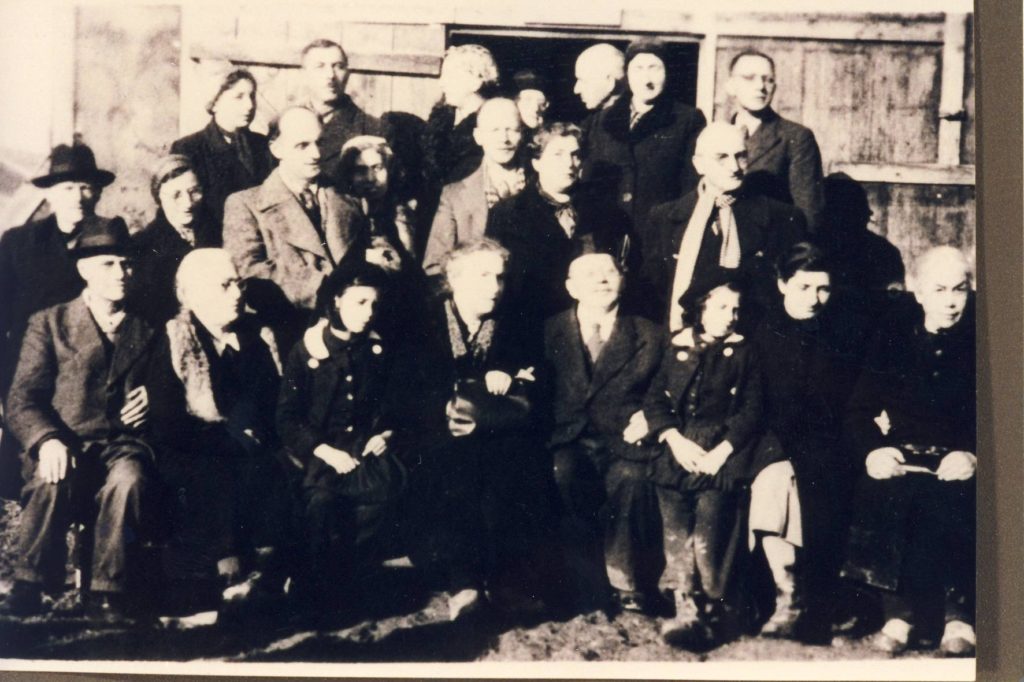

I want to stop talking about what happened to me; I’d rather go back to my parents again. From the time that I left Germany, until they were sent to Auschwitz, I stayed in written contact with my parents. At first, of course, we could write directly. When the war broke out, we could not because England and Germany were at war with each other. We could not write directly, so there were some Red Cross messages, not many. They were brief—you could only write 25 words, and I believe that even included the address. But my parents know some people in France, in Holland, and in Switzerland. In fact, actually I think, the family—one of the families in Switzerland was…somebody was, I think it was the wife came from Kippenheim and married somebody who was Swiss, I think. And they would once in a while come to visit in Kippenheim. They had a daughter—they had two daughters, but one of them was my age, and we used to play together. So that was one of the contacts. Because we also would write to each other when I was still in Germany, so that was one of the contacts. And my parents would, you know, write a letter, and…I mean…it would be written to me, and they’d put it in an envelope and send it to these people in Switzerland or France or Holland, and then they [the contact] would put it in another envelope and mail it to me. And I would do the same. I would write, address it to my parents, I mean, the letter would be, you know, “Dear Mother and Father,” and then they [the contact] would send it on to my parents. And it took longer that way, but you know, we stayed in touch with each other, and sometimes, you know, they, [we] had to be careful what we would say because, you know, some of the letters were opened by censor, or you didn’t know which one would be.

In October 1940, on October 22, 1940, all the Jews from Bäden—Bäden is the section of Germany where I come from, and Württemberg also, were sent to camps in France. They were given very short notice and they were allowed to carry with them a hundred kilograms—no fifty kilograms, a hundred pounds. And they could take a certain amount of money, I don’t remember how much, maybe I never did. They could take some money with them; and a lot of those things I understood later on, not from my parents, but I learned later on, a lot of those things were taken from them before they ever even got there. And some of them were taken from them when they were there because when they got out of whatever mode of transportation, by truck ultimately I guess they got there, they were told, you know, just dump your luggage in this one heap and you will get to it later. And you know, some was there and some wasn’t there.

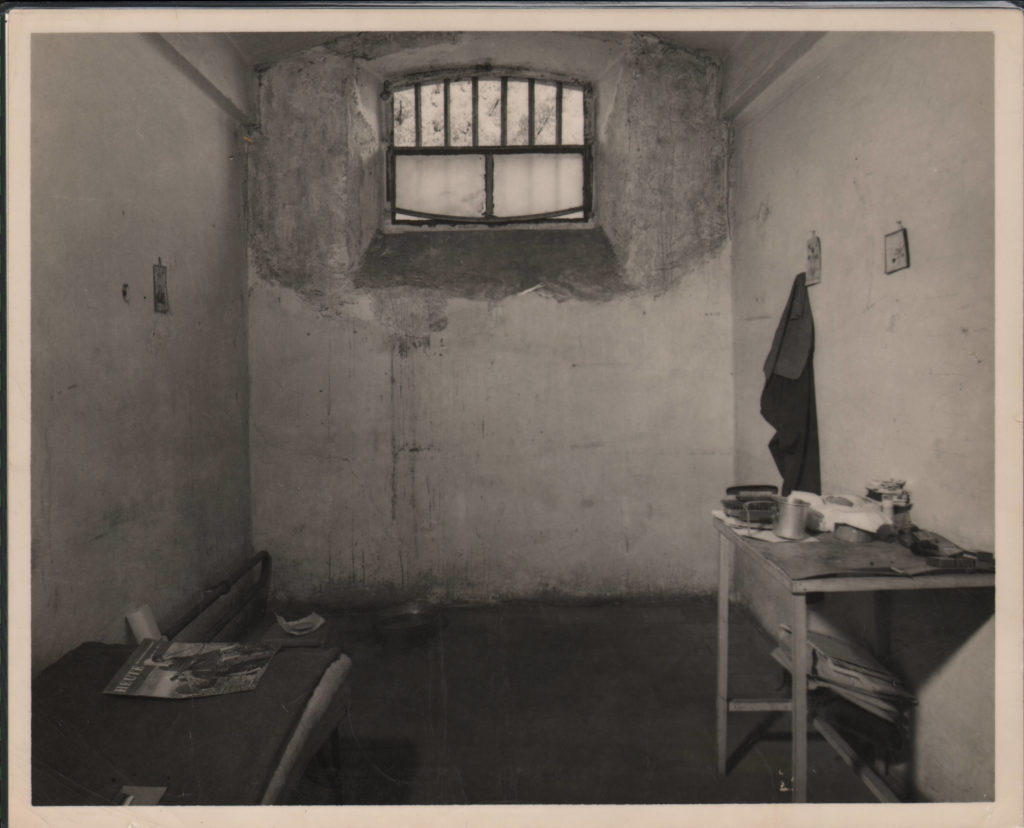

The camp that my parents were sent to, and really all the people from Kippenheim, all the people I think at that time, or if not all the majority, the vast majority of them were sent to a camp called Camp de Gurs, which is in the French Pyrenean Mountains, no the foothills of the Pyrenean Mountains, and it was a camp that had been built during the Spanish Civil War to accommodate refugees from the Spanish Civil War that came across the Pyrenean Mountains. And in fact some of them were still in the camp. And this was in Vichy France—in unoccupied France—and the guards were French, but it was under German supervision. And the camp was separated by, there were sections of the camp, and they were separated, as I understand, by barbed wire and there was a gate. And you had to have permission to go from one section to another; and men and women of course were separated. Now I didn’t know any of this from my parents. This is stuff that I found out later because my parents just didn’t want me to know what was going on there.

I mean, the first letter that I got from my parents, I think some of it was probably because they didn’t know what they could write, and my father said—they were rather cautious words—he was saying, as you will note at the top of the letter is the new address, which is, as you will notice, we have changed our address. And apparently they—and this is another thing that I found out later on—they could get…request a pass to be together for one hour every month, I think. And, but there must—there certainly also was some, you know, the people would go to the barbed wire, and they’d see each other and so on, or they’d—or maybe you would…maybe go and see your wife and then, you know, my mother might be there, and she would give you something to give to my father because you knew him…that sort of thing.

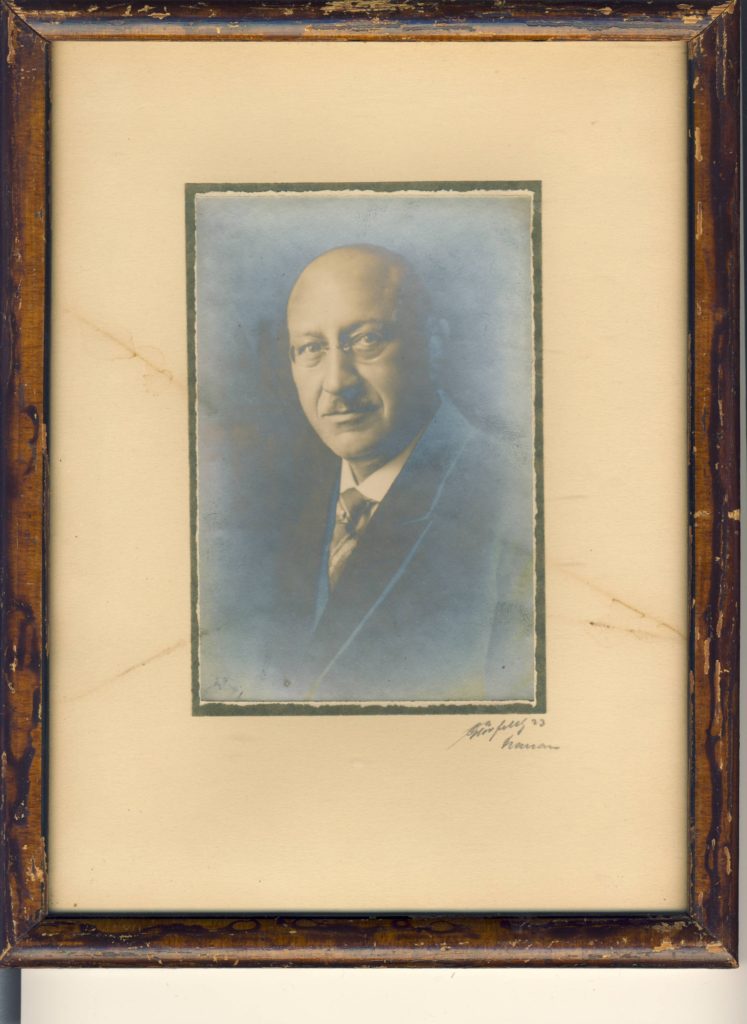

The conditions there apparently were just awful. It was just a sea of mud in the winter. It’s very, very cold there. There was a cemetery there that was started there by the people, the Jewish people there, and the people who died there were actually buried, and they were buried in the order in which they died. So the one who died first is in the far right corner of that cemetery, and you know, going that row and the next row. And I was, you know, I was there in 1980, and I looked. The tombstones have in Hebrew, well, the tombstones that are there now were put there after the war. There were some very primitive markers there before. And each tombstone is a rectangular tombstone, and it says in Hebrew the equivalent of “Here lies,” and then the name of the person, and the year of their birth, the year of their death, and the town or village that they came from. And, there are about 1,250 graves there, and I visited each grave. The first one I went to was my grandfather’s because my grandfather died there two months after he got there. And I knew that he died there because my mother told me. And he probably died because of the diet—he had to keep a very strict diet; he had some problem with his stomach, and you know there was no way of keeping a diet there.

But I visited each grave, and the thing that impressed me was in the first two months or so the vast majority of the people that are buried there, died when they were either old or very, very young like, you know, three years old…two years old…one year old. It is hard to believe less because, you know, it might have said 1940 year of birth, 1940 year of death. There were a few people, you know, I’d say in their thirties, or forties, or twenties, but most of them were very, very young or the older people in their seventies or so.

In the spring of 1940, my father requested to be transferred to a camp near Marseilles because there was an American consulate still functioning in Marseilles, and he wanted to register with the American consulate. Let me backtrack—I forgot to say something earlier. My parents had been registered in Germany with the American consulate, and they had been…had been able to get an affidavit from my mother’s brother and his wife and the woman that my aunt worked for. They—my uncle and aunt had come to this country in 1938, and they were able to give an affidavit after I left Germany for my parents. And they [my parents] were registered with the American consulate, and they were supposed to go to the American consulate shortly after they were deported to France, so they missed that. And my—and I don’t really know whether they would have been able to get out of Germany at that date. And then my father requested that transfer, and they…I mean, it doesn’t make sense that you can ask for a transfer from one camp to another, but he was sent to that camp. And he did somehow or other register at that American consulate—I don’t know how he did that, all he said was he did it.

And they [my parents], again, had an appointment with the American consulate in October 1942, but again, they did not make that because on the 19th of August 1942, and that was not something I knew then, it’s something I learned much more recently, my father was sent from Camp Les Milles, which was the camp near Marseilles, to Drancy, which was a camp just outside Paris. It was a collection center for…where Jewish from all over France in camps, or if they lived, you know, out in the community, were sent to Drancy. Well, no, he was sent there before the 19th of August. I don’t know exactly when, but my mother wrote me later that the last time she had heard from my father was probably the 12th of August, and that he was saying that he was being deported, so it was probably, maybe the 13th or 14th of August that he might have been deported to Drancy. And then from Drancy on the 19th of August 1942, he was sent to Auschwitz. Whether he arrived in Auschwitz alive or whether he died on the way or whether he went straight to the gas chamber, I don’t know. I don’t think he was sent to work, because he would have had a number and there would be some record of him. So I don’t think he ever went to work; he may not have been alive when he got there.

He wrote to me shortly before he was deported. He said, “I’m going to be deported tomorrow.” And it was actually the day before he was deported. “I’m going to be deported to an unknown destination, and it may be a very long time before you hear from me, but I will try to stay in touch. So don’t worry about me.” My mother wrote to me on the 1st of September saying, “Tomorrow I’m going to be deported.” And in fact, it was the first time that my mother ever complained. My father never complained. And that’s the first time my mother complained, and, I mean, you can hardly call it a complaint to say, you know, the last few weeks have been very difficult for us, and she said the last time she heard from my father was on the 12th of August. And she said a lot of people have been sent away, and she said that tomorrow is my turn. And then, she also said that it may be a very long time before, you know, I’ll hear from her again and she’s asking me to be brave, to carry my head high, and to be good—you know, all those kinds of admonitions that a parent would give his or her child. And, uh…she’s saying that she’s hoping to meet my father somewhere because then they can carry their lot together with dignity.

Uh…there was one more postcard from her which was dated. She dates it, and it was postmarked the 4th of September 1942, and she is saying, I mean, she must have known something, and I don’t know what she knew. She was on her way to Drancy, and she’s mailing it in Montauban which is immediately north of the camp that she was in. And she is saying, it’s hard, there’s no way of saying it in English, but it’s a very final good-bye. And she is saying, “Traveling to the east and sending you these final good-bye greetings from Montauban.” And that’s all she said, signing her name. And she was supposed to, scheduled to go to Auschwitz on the 11th of September 1942. And again, I don’t know if she arrived there alive or if she went straight to the gas chamber. There’s also no record of her there beyond that. So if she had a number, I think, she would have probably gone to work. Judging by information that I have about other family members, my mother would have been the very last one to go because others went earlier, died in France, or were sent to Auschwitz or other camps; um…my mother was the very last one.

I also forgot to say before, in July 1942 my mother was sent from Camp de Gurs where she had been with my father and then my father left. She was sent to another camp, to Camp de Rivesaltes. And she was saying that all unattached women were sent to Camp de Rivesaltes. And I remember the feelings I had, the thoughts that I had when I got that letter which was written after she arrived in Rivesaltes, and I wanted, I took something out it that, I guess, my mother wanted me to feel that way, and she succeeded. It’s only later, you know, like when I read the letter now it says some other things to me, but she’s describing what she’s seen on this trip. And one of the things that she saw from there is the…this um, what is it in Lourdes? The uh…

Eidelman: The shrine?

Epstein: The shrine in Lourdes. And she’s saying, you know, it’s so indescribably beautiful that words are not adequate to describe it. And she said how great it is to see something like that, you know, to know that there is something else to life besides the everyday humdrum of camp life. And she’s describing the tropical trees that she’s seeing as they’re approaching the Mediterranean, and, you know, she gets a glimpse of the Mediterranean. And so, my mother had a nice trip. I wish I could have gone on that trip with her. That’s what I took from that letter at that time.

Not the other things which she’s also writing like, for instance that they were met at some point by some nuns who gave them bouillon which was probably one of the most nourishing things that they had in a long time. And how when they finally got to their destination, they had to walk with their luggage, whatever they had, their little packages, on a very, on a stony, hot, dusty road for about an hour. That was not important, that was not what I wanted to hear. I only wanted to hear the good things, and I guess I needed to believe that, that that was one way for me to survive then, I could not deal with any…had I been older, maybe I would have, you know, I could have been able to read between the lines and asked a lot of questions, but I…whatever they told me…I wanted, you know, that’s what I believed. Or you know, maybe I would write to them, if I had a boyfriend, had a problem with a boyfriend, and, you know, my father was quoting Schiller and Goethe and talked about the storm and stress years—that sort of thing. So, you know, what’s different is how it used to be at home, you know, and I wanted to believe that.

And when they [my parents] said it’s going to be a long time before I will hear from them, well, they said so—and how long is a long time? And so it was 1943, and it’s 1944, and that’s a long time, but they said it’s going to be a long time. Maybe it’s really a very long time, and maybe I have to wait until the war’s over. And so I pinned all my hopes on that. And then the war was over. And well, you know, it’s going to take a while before—and, of course, they might have lost their address book. And even if they have it, I have moved several times since then. So maybe the mail isn’t being forwarded. And, you know, I made one excuse after another. Maybe they’re suffering from amnesia, and who knows where they are.

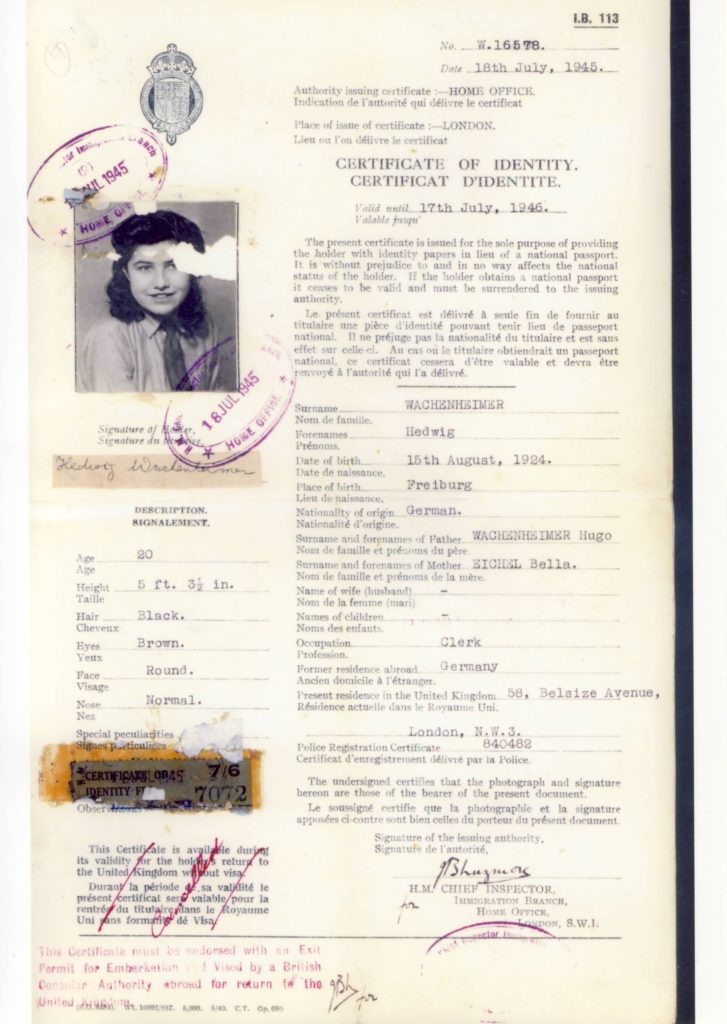

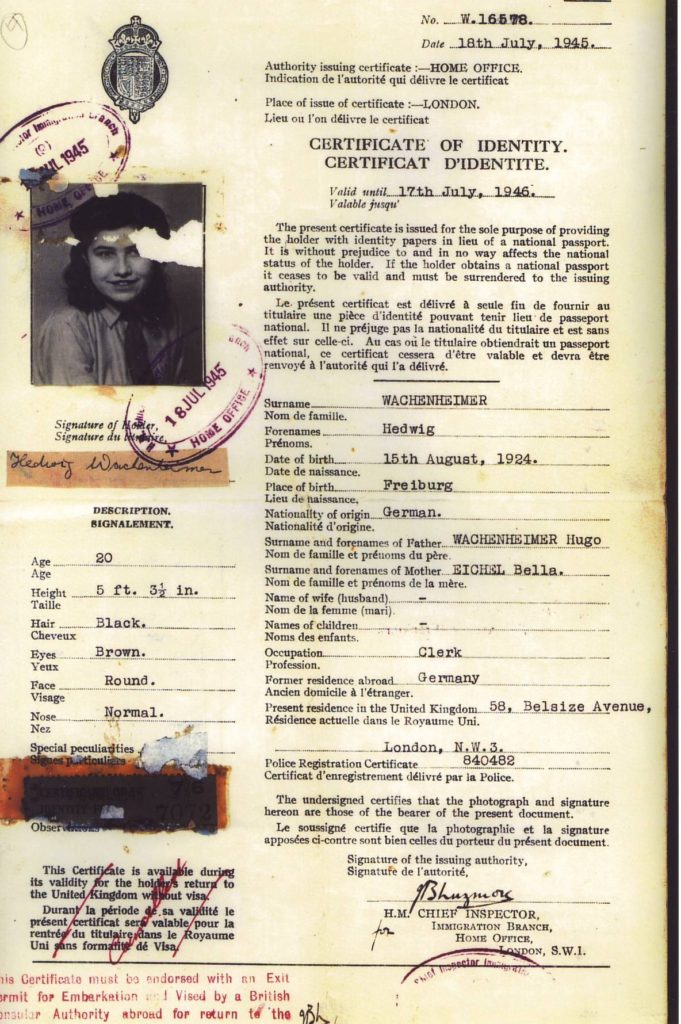

And I went back to Germany in the summer of 1945. I had a job because I could not afford to go back to Germany on my own, and I mean, I had no money—let’s put it this way. And part of the reason was to be in Germany, to maybe go back to Kippenheim to see if they’re there or to be closer to where they might be—where I might find them. It was not until the summer of 1947 that I was able to go back to Kippenheim. I tried, and one time I even went as far as one stop on the train and turned around and went back…because I was afraid. And I think what I was afraid of—I really knew if I go back there, they’re not going to be there. But if I don’t go there, and I’ve not written to anybody there and asked whether they’re there, then I can still believe that maybe they’re there.

But finally, in the summer of ’47, you know, I said I’m not going to be, I’m not going to be here that much longer, and I may never be able to come back, so you know, if you want to go, then go, and never mind all those feelings, just go. And I literally forced myself and talked myself into going, and I went. And I was, you know, I realized when I went there that, you know, that door is now forever closed. They’re not there, and I can’t tell myself they’re there. But you know, they may be elsewhere. And it was not until I stood on the ramp in Auschwitz in September 1980 that I finally accepted the fact that they are indeed dead. So that’s a very long time to carry that hope. But I…you know…the thing is I’ve not seen their bodies. I’ve…there is no record of their deaths. Nobody knows that they have died, or if there is somebody that knows, I don’t know who that person is. And…so—I don’t want to believe it.

Eidelman: What happened when you went back to your house in Kippenheim?

Epstein: Well, I walked from the railroad station into the village and I had to actually walk right…I didn’t have to…I could have gone another way, but the way to go because I decided I wanted to go to City Hall, and so the way to go is to actually go right past the house. And I almost didn’t quite dare to look at it because I was afraid. I mean, I had the fear of November 1938 that the Nazis are all around me, and they recognize me, and they know I got a big “Jude” on me or something like that. They know that I’m Jewish. And so I kind of glanced out the corner of my eye; I didn’t quite dare look at it. And I went to City Hall and I asked to speak to the mayor, and I explained who I am and why I’m there. And um, asked that he…I said, “I want to go to the house, and I want to go to my grandmother’s house, and my aunt’s house and my uncle’s house. And I want to do all those things. But I don’t want to go alone, and please, can you go with me, or have somebody go with me because I am just afraid.” And he said, “I will go with you.”

And on the way there, he said to me, “You know, how during the war, they [the houses] changed, they made efficiency apartments out of the house, and so things are different, and I know some of the families that live there, and I’m sure they would be very glad to let you in and show it to you, and I think you will want to see it.” And I said I did—until I got there, and then I said, “No. I don’t want to go inside, because it’s not going to look anything like I remember. And I want to remember it the way it was. I don’t want to disturb that memory with or superimpose something else on it.” The outside of the house, I mean, it looked dilapidated. You know, there were…there must have been some shrapnel or something, or some shots that went through the house. There were holes in it, and it’s, you know, like the shutters hadn’t been painted, they were peeling. It looked very rundown, but, you know, very recognizable. The streets, sidewalks, the street had been widened. And so some of the front yard that we had was gone, and so it looked a little bit different. There was a big tree on the side of the house that was no longer there. And, um, but I did not want to go inside.

And in fact, I went back there again in 1970 with my husband and my son because, especially, I wanted my son to see this is where I come from, roots—roots before Roots. And I remember my husband saying to me, “Now, go inside.” And I said, “No, I don’t want to go inside.” And he said, “Look, you come all the way from the United States, and you’re going to go back, and then when you’re back, you’re going to say, ‘Oh, I wish I’d gone inside,’ ” and he says, “You know, you’re not going to be able to come back—just to go inside the house—so go inside.” And it was almost like an argument because he was pushing me to go in, and I did not want to go in. And I didn’t, and I…I’m still…I have no regrets. I don’t want to go in unless it were the way it…you know. I mean, it might not be the way it was then anyway, but you know, the walls…there are going to be walls where there were no walls. It’s not going to be my house, or my parents’ house.

The interesting thing was, you know, in 1947, when I was there, and in 1970, both times, I wanted to go to the cemetery which was in another village, in Schmieheim because family members were buried there. And I just wanted to see whether those graves are well taken care of. And if not, I wanted to do something about it. And I, both times, I forgot to go. And it’s interesting because probably the parent in me saying that I’m still a child, and I can’t go because as a child, when there was a funeral, I was never allowed to go to the funeral. I was never allowed to go to the cemetery. My mother would say, “That’s not for children.” And so in 1947, I’m an adult…I am back there, and I wanted…and I said these are some of the things I want to do, but I forget to go to the cemetery. In 1970, I go back, and I want to go to the cemetery this time because I forgot the last time, and this may really be my last time here. I really want to go, and we were back in Switzerland when I remembered I didn’t go to the cemetery. So I guess I reverted back to being a child, and my mother said, “You can’t go,” so I can’t go. (SIGHS). And I think I’m going to have to take a trip and go there one of these days. Just maybe that will be the only reason I’m going is to go to the cemetery.

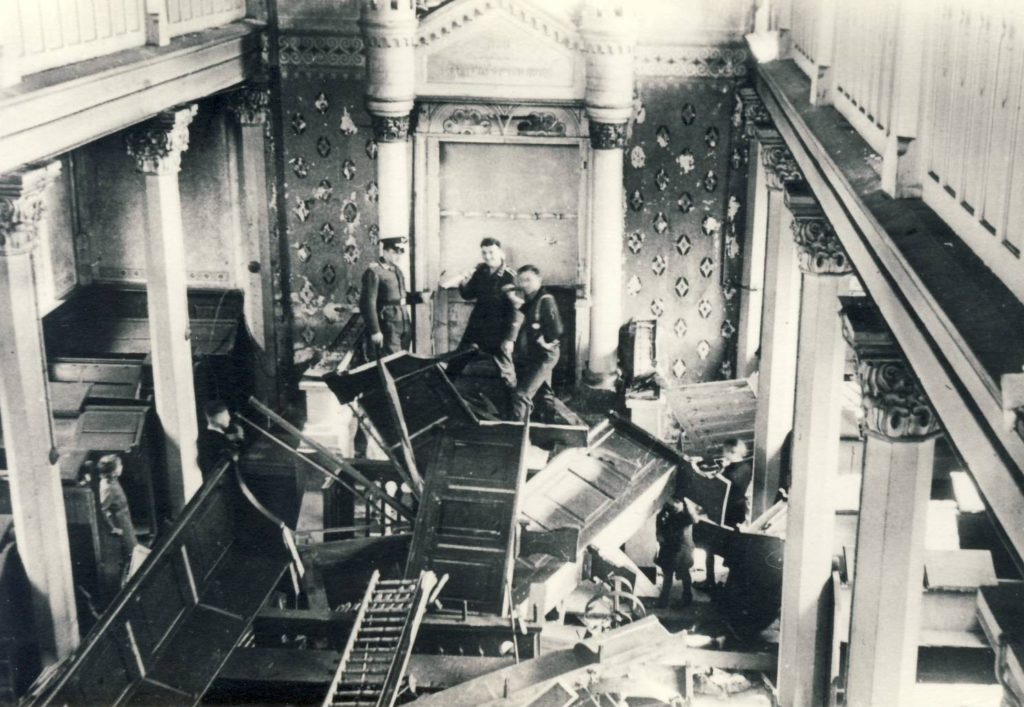

Eidelman: After, going back to Kristallnacht for a second…did…were you aware that they had done damage to the graves in the cemetery at that time?

Epstein: I don’t know whether they did… I really don’t know… If my parents found out, and I’m sure they did, I’m sure they went, but they didn’t say anything to me… So I don’t know… And the cemetery is there, I know, and I don’t know just in what condition it is… What the graves look like, you know, my family’s graves looked….(LONG PAUSE).

Eidelman: When we spoke on the phone, you mentioned about something, that you found out something.

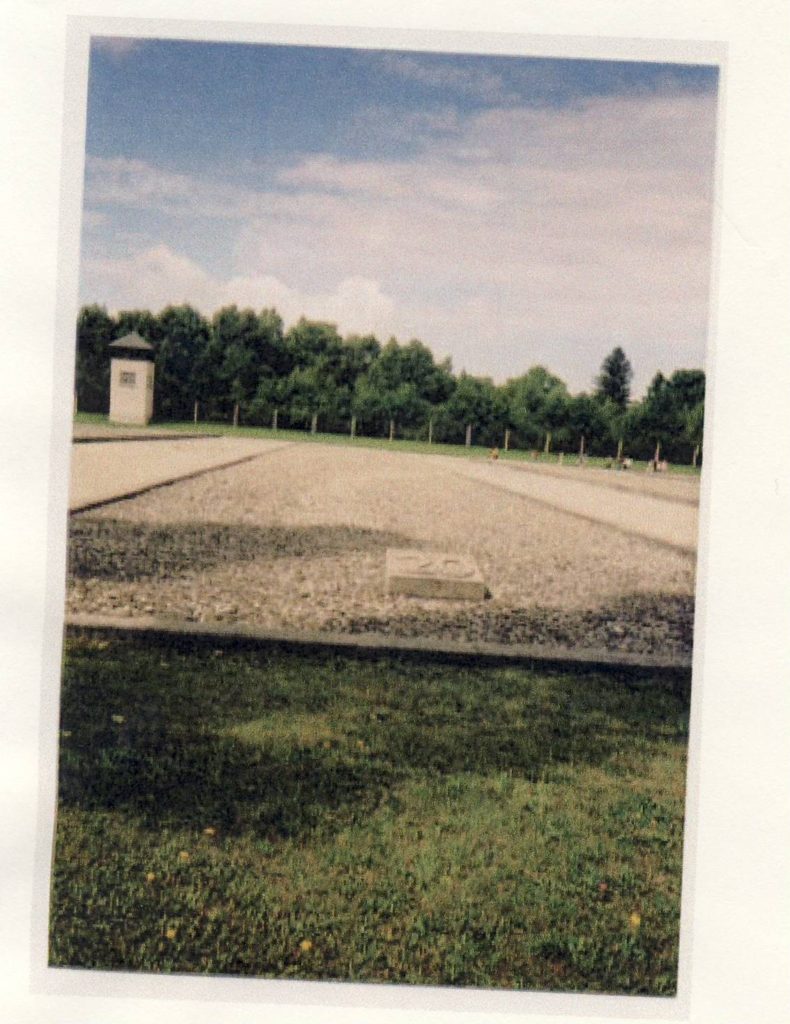

Epstein: Well, you know, I don’t remember what specifically I told you then. But you know, just last week I found—I got something from Aroldsen, the international tracing service. And they gave me my father’s prisoner number in Dachau, which I didn’t know. And they gave me the transport number of my mother, the transport that took my mother from Camp de Rivesaltes to Drancy. I didn’t know that. There was some other information about other family members that I got that I didn’t have, but I had not done as thorough a search on that before. It was, you know, mainly concentrated on my parents and trying to piece together all of, I mean, I feel like there’s this giant puzzle and I’ll never be able to put, to find all of the pieces. But every once in a while, there is a little piece, and, no…when I went in 1980 to France to visit Camp de Gurs, and then I went to Dachau and went to Auschwitz, I was, you know, I don’t know how much I found there, but I got more understanding and a feeling for what the area was like, you know. What, you know, I mean, Auschwitz, I’d heard of it, but you have to see it. And to see Birkenau, which was really, you know, the sister camp. I stood in the middle of the camp, and, you know, when you look off in the distance, it seems like the horizon comes down and meets the earth. Well, the camp goes beyond where you can see. You know, you have to see this to comprehend it.

Well, for instance, when I went to Dachau, I had…to me…Dachau has always been a concentration camp. Well not always, but say since 1938, since Kristallnacht, it’s been a concentration, and only a concentration camp. And I remember, when I got to Munich, and I asked how to get to Dachau, and people would very matter-of-factly tell me…well, you take the so-and-so train, and it takes about an hour. And I expected them to be absolutely horrified when I asked to go to Dachau. You know, or they’d think, “Why would she want to go to Dachau?” And you know, very matter-of-factly, like if I had asked somebody how to go to Chicago, they wouldn’t be horrified, they’d tell me how to go. And when I got—when I came to the end of the train ride, and got out, there was this quaint little beautiful, little town—it was Dachau. And I realized, you know, that’s why these people weren’t shocked. They thought I was going to a town and not to a concentration camp. And I knew that the camp was named after the community that it was in, but to me Dachau was just a concentration camp.

And the other thing that I remembered was the barracks number that my father was in…was barracks number twenty. There are only a couple of the barracks left, and number twenty isn’t left anymore. But there is a marker there where number twenty is, and I found it, you know. And, you know, like I’m a very tactile person, and so…there is like a cement base is there…you’ve been to Dachau?

Eidelman: Yes.

Epstein: But you know, I walked all around, and I touched it, and I, uh, took a stone, you know…the stones, and I took a stone from there and, uh, I took that stone really because I knew I was going to Israel the following year for the Gathering of Holocaust Survivors, and I already knew at that time that they, that they recommended you bring a stone to Israel with the name of your loved ones engraved on it so it could be used for the construction of the monument to those who didn’t survive, and so I was going to take a stone from there, and it was going to be for my father, and you know, but…what more appropriate stone than from there? I mean, I had some feelings about taking something away from there, but then I thought, and I’d say…no…my stone alone isn’t going to make any difference, but what if everybody should say that? There wouldn’t be any stones there, but I still took the stone. I had to. And I did the same in Auschwitz. I took the stone from there, and um, that was for my mother because there was no stone that I…well, I had a stone that I picked up in France, that’s really what started it.

And I think in the back of my mind, it must have been the stones in Israel and the memorial. But as I walked away from the Camp de Gurs, I was feeling very, very sad, and I was looking down at the ground as I was walking along this road. And all of a sudden, I had this really strong feeling that this one stone said to me, “Pick me up. Take me with you.” And you know, I didn’t hear any voices, but it was just that strong feeling, and so I bent down and picked up this stone. And there were a number of stones, you know, like on the side of the road there are always stones or rocks. And I…it was dusty…and I wiped it off, and I looked at it, and it was a pretty stone. And I didn’t think much about the stone, I mean, much more about it other than, you know, yes…I’m going to take this to Israel. And I will pick up stones in the other camps also.

And it wasn’t until ten weeks after I was back in the United States, and I had shown that stone and the other stones, you know, to people, that somebody said to me, “Do you realize what is on that stone?” And I said, “No, what is on it?” “There is a Mogen David on that stone, and it’s not perfect, but it’s there.” And I took it to a geologist because I needed to know if it’s man-made or nature-made—either way it’s a phenomenon, but it’s more so if it’s nature-made, and it’s nature-made. If you’re interested, I have that stone. I will show it to you later on. I was not able to leave that stone in Israel. I took it with me, and then I couldn’t leave it there because there was just a very special stone. And you know, I’m a person who’s very…who’s got her feet on the ground, who’s not off in the clouds somewhere, but this is really a mystical experience, I think.

Eidelman: When you went back to Kippenheim, did you feel…what about this house? What did it, you know, what its value is, and did you receive any reparations for it or ask any reparations for it?

Epstein: No, no. Because when I…this was when I went in ’47 to see the mayor, there was some difficulty there at first when I said who I was. He looked up in some books…something…and he said that “Hedy Wachenheimer is no longer alive. She died in an air raid in London.” And I said, “I’m Hedy Wachenheimer, and I lived in London, and there were air raids, but I was never even hurt, much less died. I mean, I have some identification that I can show you.” And apparently my father’s sister’s daughter, one of her daughters went to Germany soon after the war was over, and, uh, was a…