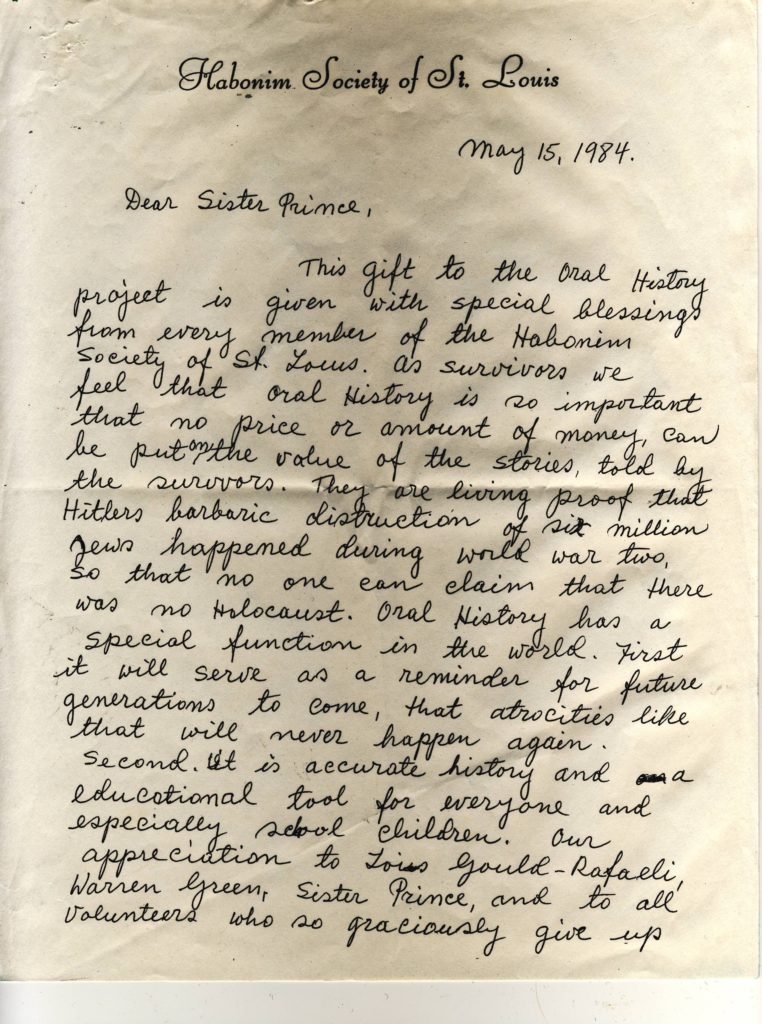

PRINCE: My name is Vida “Sister” Prince, and I am interviewing Toby Cymber Gutterman about her husband, Murry Cymber. Today is October 16th, in the year 2000.

GUTTERMAN: This is – I am Toby Cymber Gutterman and I’d like to tell the story, memory of my beloved husband, Murry Cymber. He passed away in 1973 and that’s why I’m doing this, because he didn’t live to do it himself, to tell himself the story.

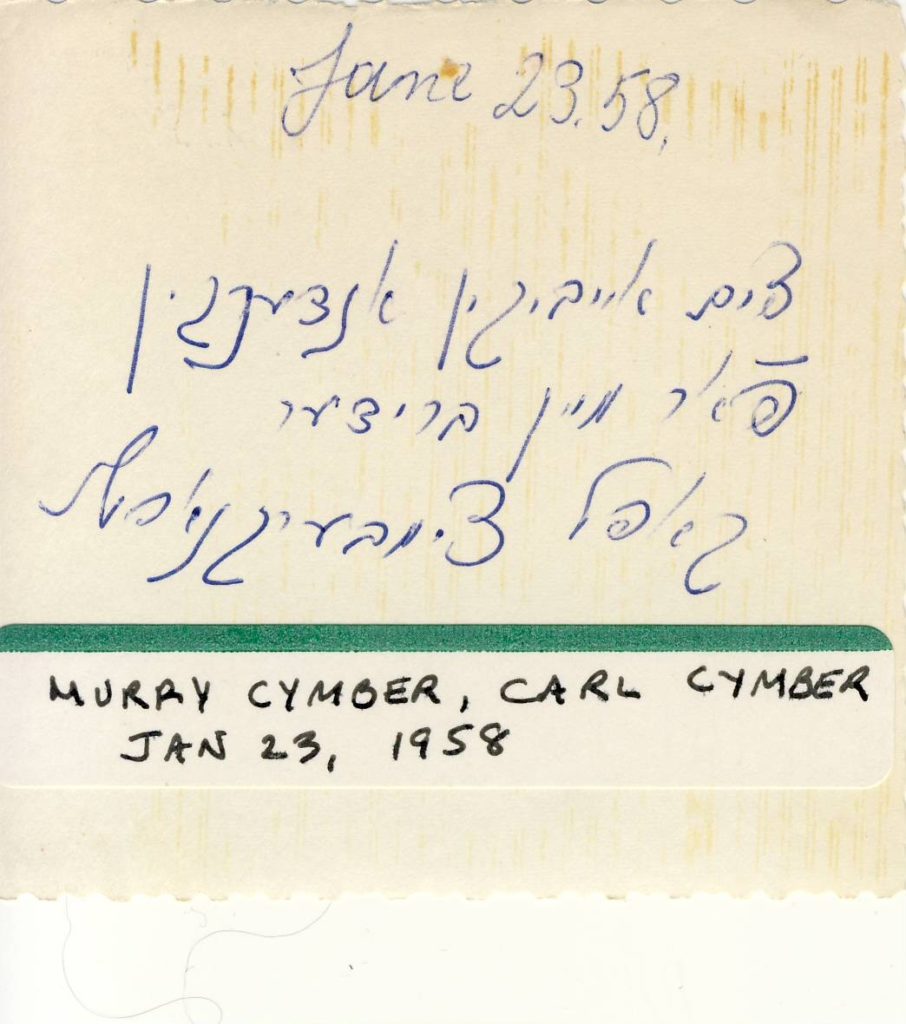

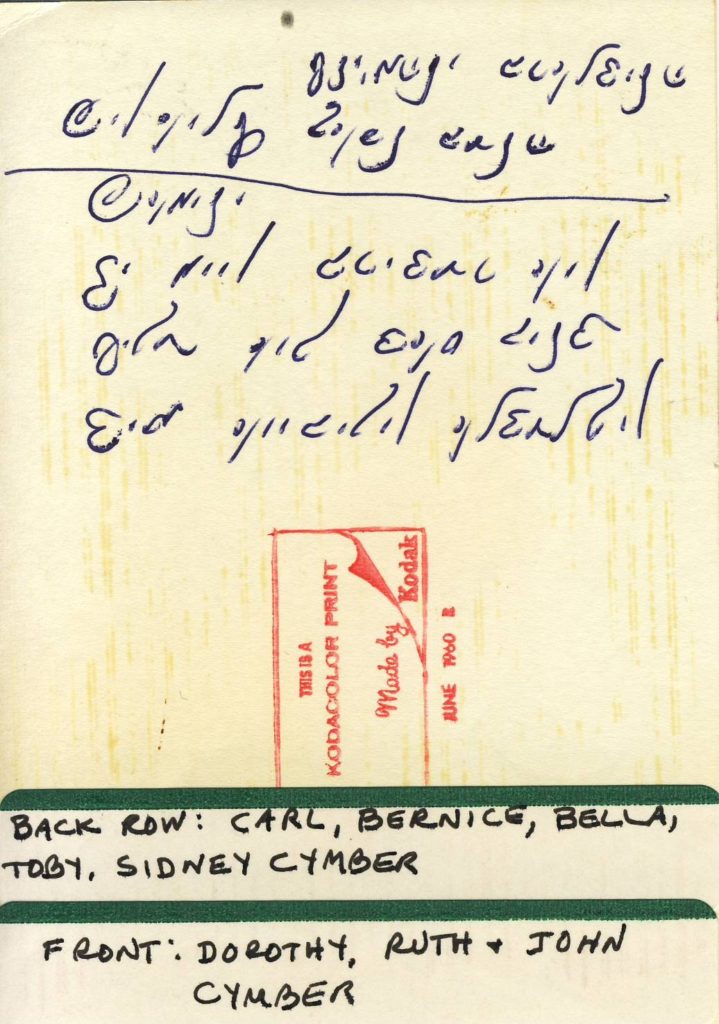

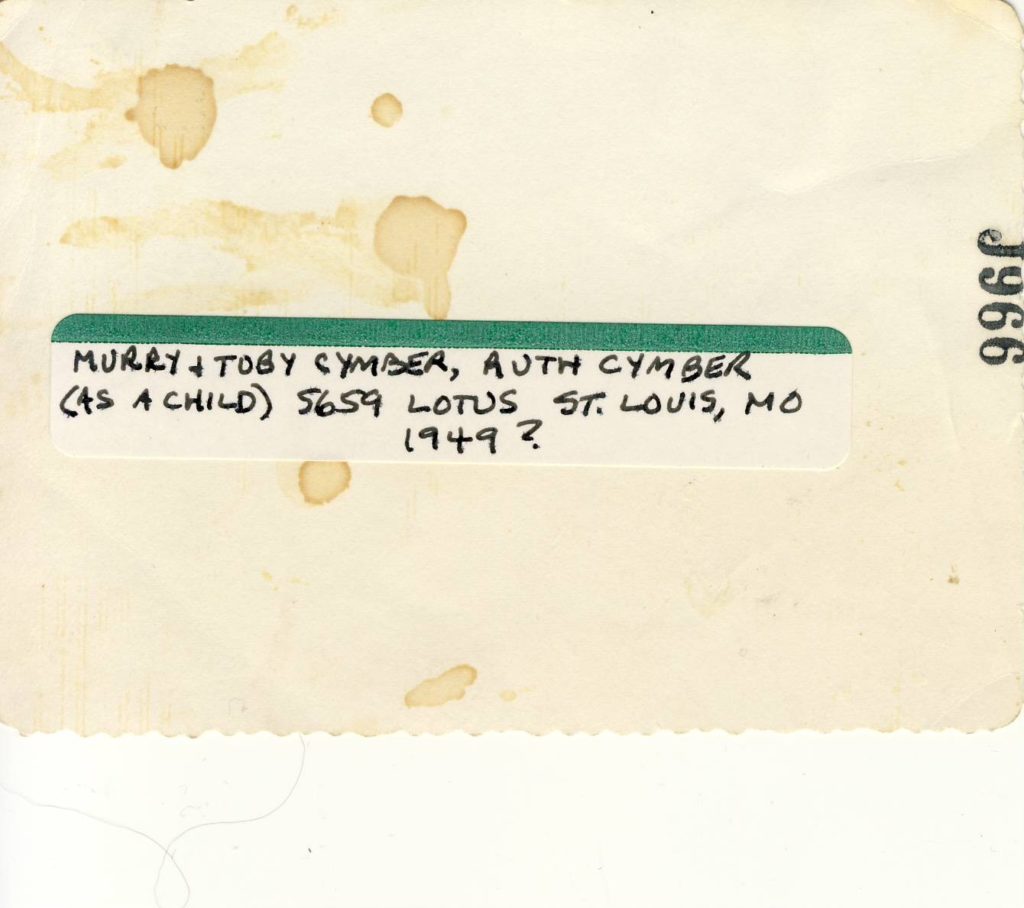

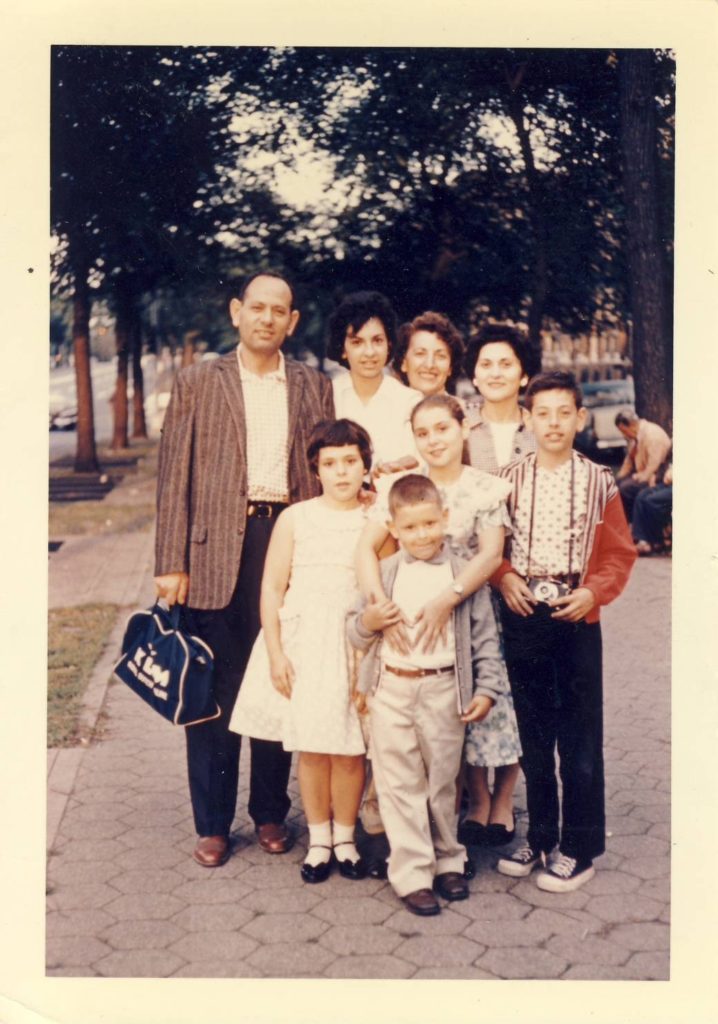

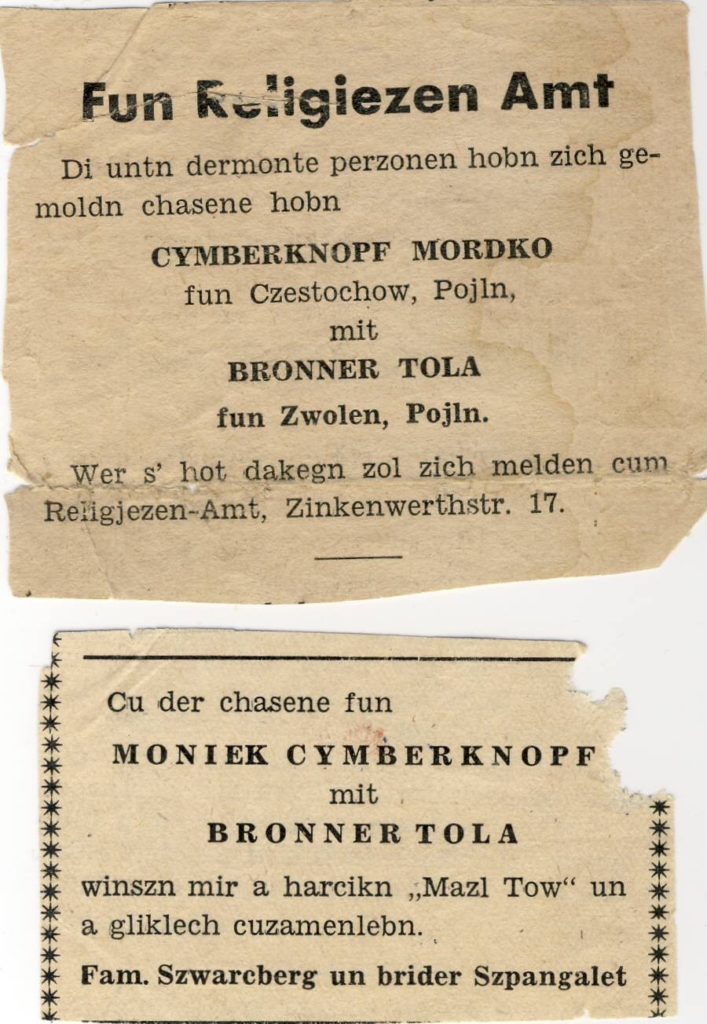

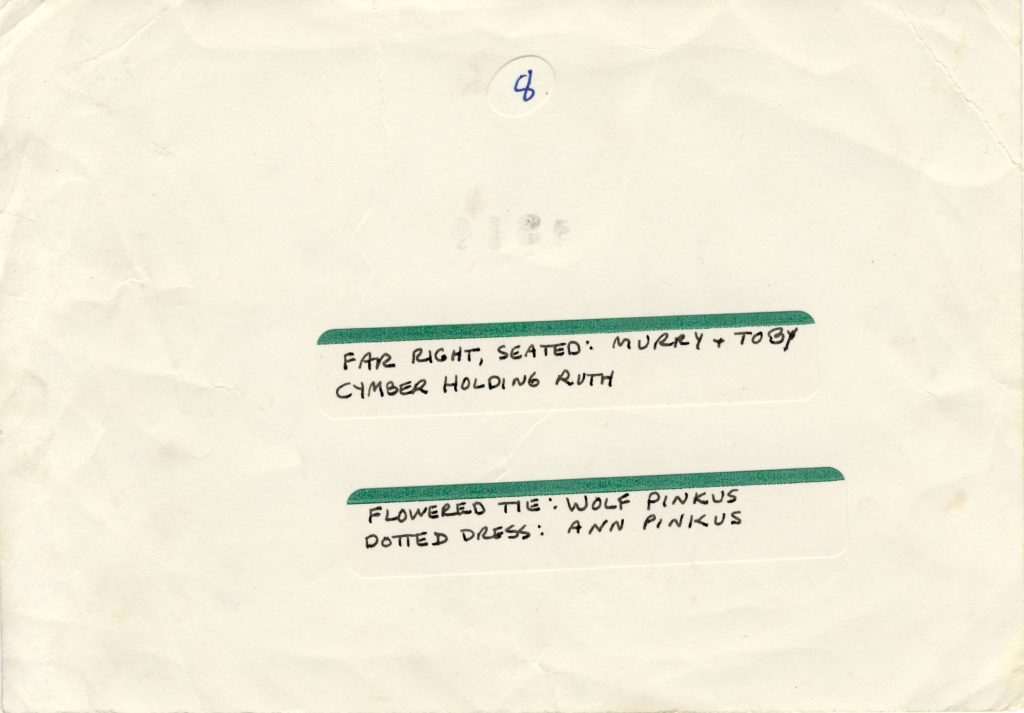

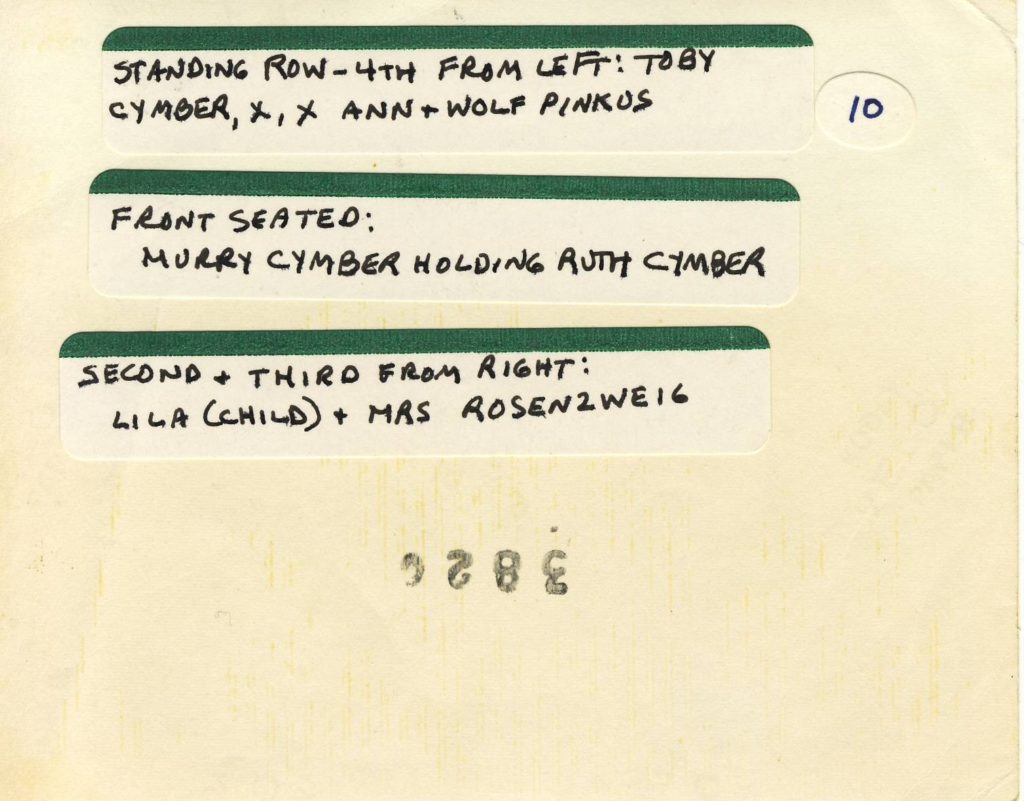

My husband, Murry Cymber, was born in Poland, Czestochowa, May 26, 1924. He changed – his original last name was Mordkha Cymberknopf, but when he got his citizenship paper, we changed it to Murry Cymber – M U R R Y C Y M B E R. His father’s name was Jakob, and mother’s name was Ruchla Cymber. His mother – Murry’s mother passed away when he was two years old. His – he had an older brother Carl and sister. He was the younger. His father remarried. His older sister took care of him because his stepmother didn’t bother with him much.

Murry was 15 years when the – Germany attacked Poland in 1939. He – the Germans, when they attacked Poland, they were rounding up Jewish males and then made them work very hard. The Gestapo got his older brother, Carl Cymber, too. Murry, at the time, at one time, loaded coals; that was hard work for a young boy. Later he worked in a metal factory. That was – that was a – in Czestochowa. They had barbed wire fence, and they watched every move everyone did. That was in 1940.

In 1941, Murry was deported to Majdanek, near Lublin, Poland. At first, several weeks, he was helping out the carpenters. Then he was transferred to a place where they put dead bodies in a massive grave and burned it. Next day, they had to cover the grave with dirt. Evidently the Germans were trying to cover up their tracks after they were finished. Murry knew that they wouldn’t leave any witnesses, so he decided right away to escape. The Germans were shooting after him, but it didn’t – they didn’t kill him.

He was in hiding in a forest, but unfortunately he got caught and taken to yet another concentration camp, called Plaszow, in Poland, near Krakow. Next he was taken to yet another camp, Gross-Rosen. Next camp was Barackenbau. In this camp they burned numbers; they burnt a number on his hand. This number was 56811. In 1942, again, he was taken to Buchenwald where they had to work, sometimes useless work. By that I mean they worked with rocks and different things.

Finally, in 1944, he was deported again forcefully to a camp called Taucha – T A U C H A. He worked in an ammunition factory. And he had to wear pants and shirts, blue stripes and gray stripes, and he had to wear wooden shoes.

Murry was liberated by the U.S.A. Army in May of 1945. After that, he went back to Poland to get his sister and brother-in-law, and also his brother’s fiance. Evidently what was happening, his sister and brother was married before the war, and they found each other, so – and his older brother was engaged to a young lady, and he found out she was alive and she’s in Czestochowa. So, I was there too, and what happened, he came over to this young lady to tell her to get ready. He wanted to get his sister and brother-in-law, and his brother’s fiance, to Germany because there was talk that they’re going to close the border in Poland; the Russians were going to do it.

I was present at the time when he went to his brother’s fiance, and he asked me if I want to go out of – get out of Poland. I said I would like to but I don’t have any money, and I just don’t have, you know, anybody could help me. So he says, “Do you have any I.D. that you have a picture in it?” I said, “Yes, I do.” He said, “Why don’t you use that? At the border the people might not read Polish, and we might get through.”

Well, what happened, one day he got to know another few people and he says he didn’t mind to take them too. So we all went first to the border, and we were turned back. We were – I just remember now that even he had some money sewed in in his hat, and they took that away. And it so happened that one of the military persons who was standing at the border, he came from a Polish family, and he could read Polish, and he knew that was not a passport. So we were turned back.

What happened – meanwhile, I learned some Russian when I was working, you know, at the Russian hospital, and this man, Murry Cymber, that I just met, he said, “If you know how to converse in Russian, why don’t we do that.” He bought two big bottles of vodka and he was, he said to tell the soldiers; they won’t stop, but they were transporting different – I’m not sure – it was gasoline or some kind of oil – it was covered up trunks. And we took a chance and went there. And I asked him in Russian if he could take us to the border, and he did. So that’s how we got through the border.

PRINCE: How extraordinarily brave.

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, yeah, he could have paid with his life. Then we went to the Czechoslovakian border and we were one day in Czechoslovkia. And this man – I don’t remember if he was Jewish or Christian – but he let a lot of people who got out of camps stay there for a day or two, you know, and we didn’t have to pay. Then the next day we were lucky. We tried to go around the side streets somewhere. One place was like hill down, and we went through –

PRINCE: Like what?

GUTTERMAN: Like a big hill going down, and it was hard to breathe and everything; we weren’t that strong at that time. And we went on a train. They let us into train, and there were people in the train, that they tried to give us some food. So I remember his sister and her husband, and also her – his brother’s fiance, and some other people, and so we were trying to get to where the United States Army was stationed because that’s where we wanted to be. We didn’t want to be in Poland anymore because – in my case – I knew my whole family was killed in the gas chambers, so I just didn’t want to be in Poland anymore.

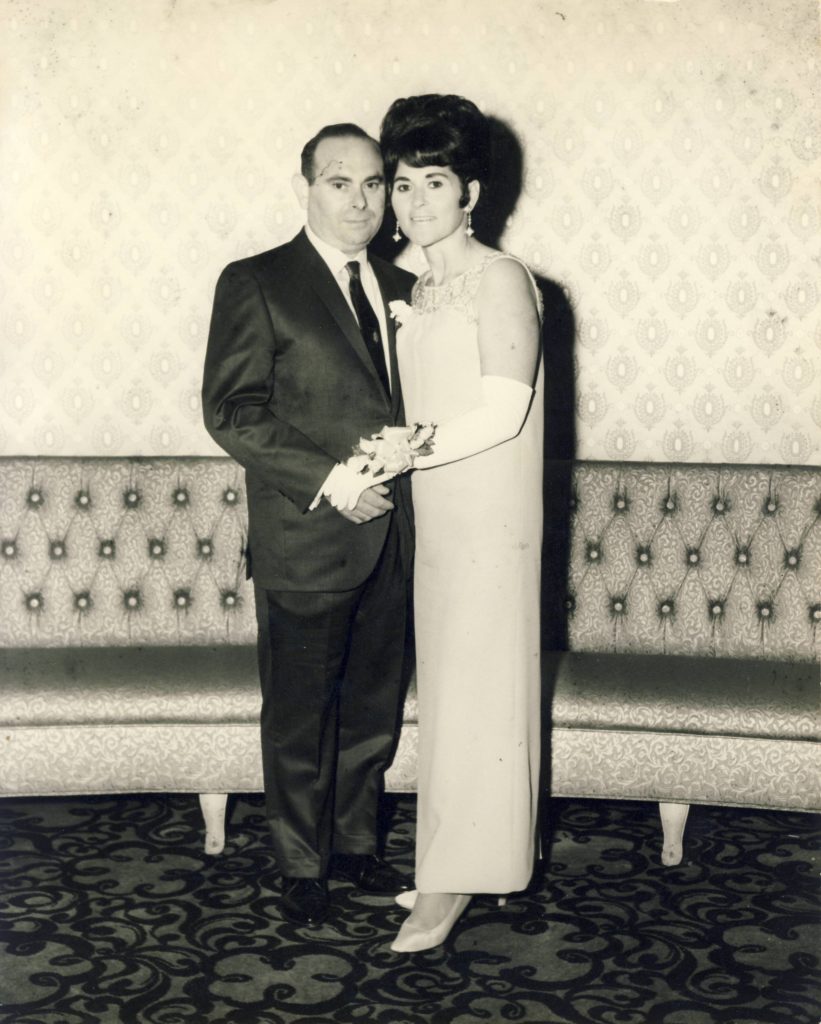

So, to make a long story short, we finally went and we got into Germany and that was in 1946. I lived in Germany for a few years, and after we got to Germany his oldest brother, Murry’s oldest brother, he got married to this girl in Germany. And the young – Murry, he – he started asking me out. And after a while he wanted to, me to marry him. And I said, I was thinking, I don’t know him that well. He’s so nice and everything. So I said I want to wait, and I waited another year until I got married.

Then, in Germany, right after I got married – it’s very sad. I remember I got married by a rabbi, he was from Poland. And shortly after, I just remember that, he died because he went into the hospital and they gave him some kind of juice directly from a can and it was contaminated with something. He died from it. It was in Germany.

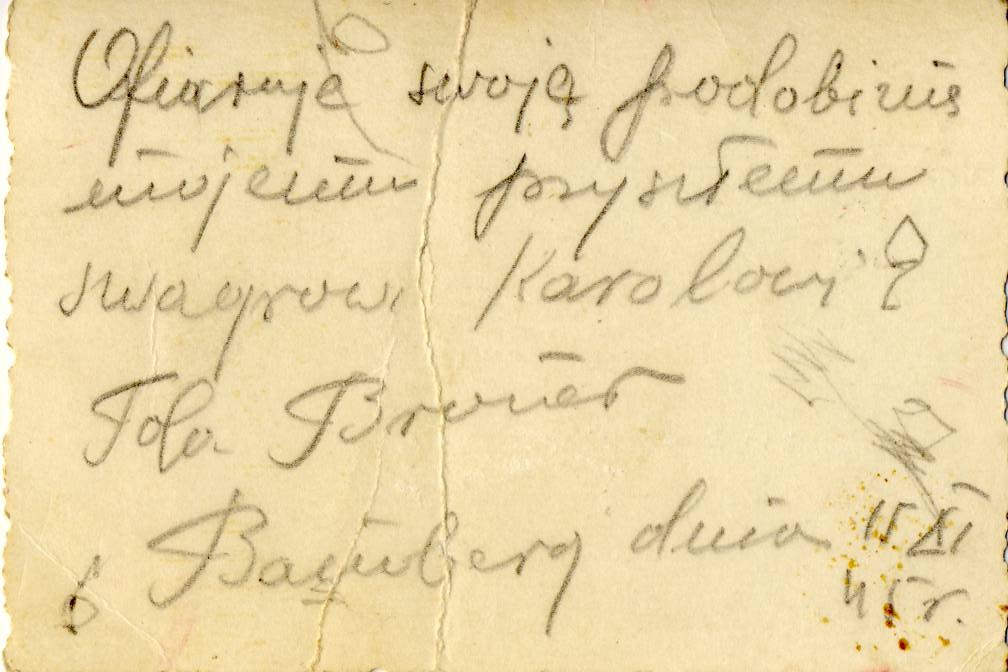

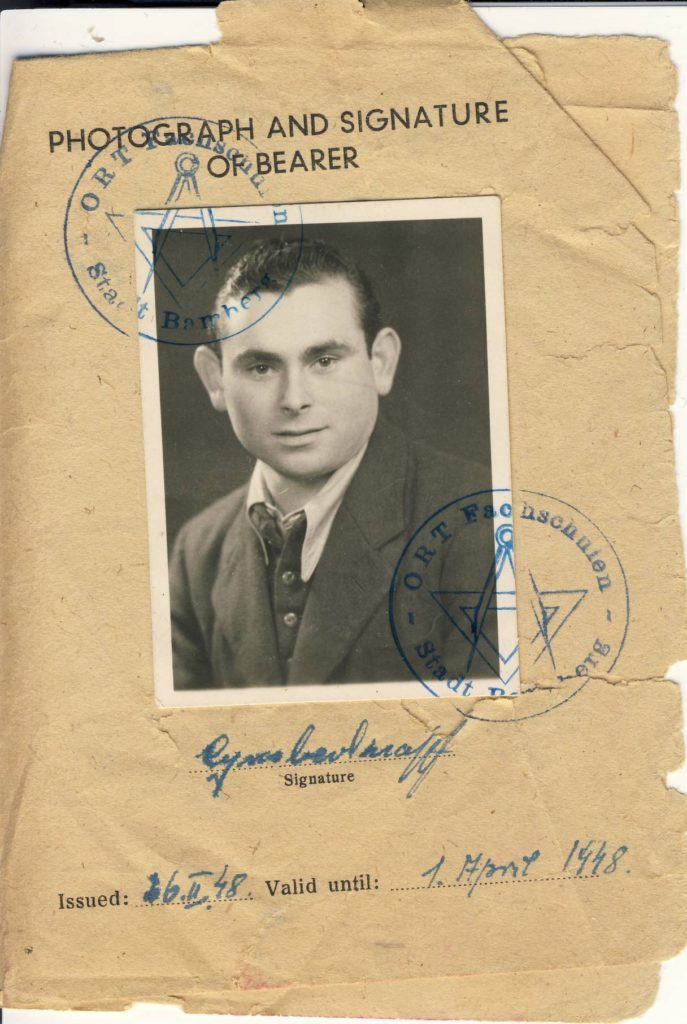

But anyhow, I got married to him and there was a D.P. camp in the city where I was; it was called Bamberg, in the state of Bavaria, in Germany. And we rented – my husband then, Murry, he found out that a lot of German families, they lost their husbands and sons, and they needed money. They had big houses. So we lived in one of those, lady’s house; we paid her some money, and she gave us – like, it was a kitchen and one bedroom. That’s all what we had. And, so what happened, we lived there for quite some time, but my husband, including myself, our education wasn’t a lot then, so we had to go to school. He went at night to school. In the daytime he found out that this organization called ORT, O R T, this is a Jewish organization who I think – who are all over the world and they helping people.

PRINCE: They train people…

GUTTERMAN: Train people to get trades and jobs. So he went there, and they actually had German teachers to train them.

PRINCE: Oh.

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, because they wanted to make a little money too after the war. It was hard for them. So, anyhow, so they helped him very much, and he needed a job. He says, “Now I’m a married man. I have to make a living.” So he says, “I’m going to try to go and ask.” You know, the United States at this time, they were building barracks. Nowadays, when our military’s stationed in other countries they have apartments or housing, but at the time it was just contemporary so they built barracks. And they asked him to work for the day to see what he can do and after the day was over they hired him. So it was a little easier for us to, you know, to live because we had some money and we could buy things at the kiosk, you know.

I was very scared at first, really, to get married because I lived a sheltered life. That’s why it took me so long, and I was – I didn’t have anybody, and I knew, you know, I was at that time – I was, I think like 20, I think, or 19 and a half. And then, next thing, I found out that an aunt, my father’s sister, is alive – two sisters actually. And so she came to visit us.

PRINCE: How did it happen? Did she contact you?

GUTTERMAN: No, she didn’t. But what happened, somebody – they were asking around and they asked for my name. And my aunt didn’t know I was married, so she asked for my maiden name, Bronner, and they – some people knew my family. She lived in a different city in Germany. So she came by and my aunt was not in a camp; they ran away to Russia and they were there in Russia, but they had a hard time too. My uncle too, and they had two children, a daughter and a son, and they came to visit us. And I was – by that time I was married two years already. So she started saying, “You’re married two years and you don’t even have any children?” And I said, “Oh no, I don’t want to have any children in Europe, not unless we go out of the country.”

Now, what we did, early on, we did not know that my husband had family – we knew that – but they’re going to sponsor us. And they did it. So we registered – I still have the registration papers with my pictures – to go to Israel or to United States, wherever it will call us first. So, they didn’t have Israel then; that was Palestine. They didn’t have a country yet. So, what happened, we found out the family, my husband’s family, lived in New York, and they were going to sponsor us. They signed a paper that they will find my husband a job and also where to live.

PRINCE: Did Murry have a preference of which place to go? Or did he just want out?

GUTTERMAN: No, we didn’t have it, because with Israel – they never called us. Of course, there was no Israel. They tried to smuggle through –

PRINCE: No, I mean, did he have a preference? Would he have preferred to go to Palestine?

GUTTERMAN: No, he didn’t have a preference. We just wanted to get out really, to tell you the truth, you know. But the way we got out, we had to go to a doctor. I still have got somewhere a paper that shows that we went to a doctor to see that we don’t carry a disease or nothing before we came here. And also, you know, it wasn’t like they had, like today, they just thought, you know, you come sick and you look right away for a handout.

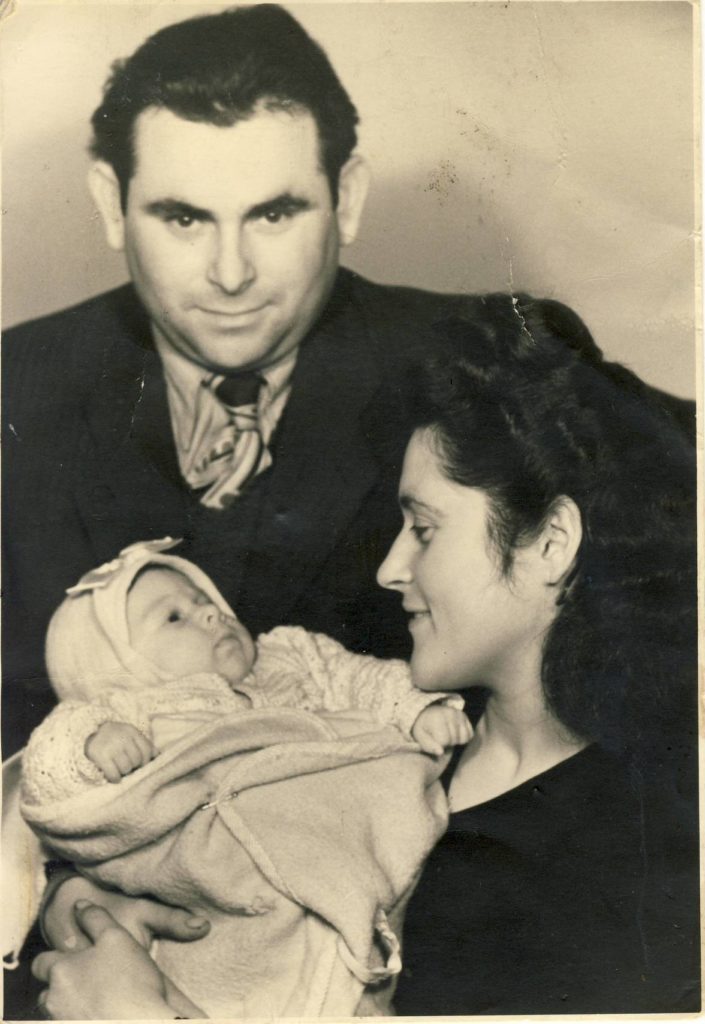

And we came; we were so lucky that my husband did, worked for the U.S.A., and they furnished a plane, and we went – they gave everyone who worked for them, they furnished a plane, and who had visas to the United States. We came by plane. Unfortunately, they would report us, and they – and I never got the paper – because, I didn’t mention that, after that, a year later, I had a child, which I wanted to have in the U.S., but I was too early in the pregnancy to go on a big trip like that. So I had to wait, and then I was too high with my pregnancy; again, the doctor told me not to go. So my oldest child was born in Germany, and she was born in 1948. And she was born in a hospital, a Christian hospital, there were just nuns, nurses. And by that time, my husband was sent from the military to Schveitfort (?) am Main.

PRINCE: That’s what?

GUTTERMAN: Frankfurt am Main, I’m sorry. (LAUGHTER) Schveitfort…Frankfurt am Main. He was working for the, for the U.S.A., for the military; that’s where they told him to go. Once every weekend he had to travel six hours to come home. So I didn’t want to bother him, you know. He didn’t come home until the baby was a day old, because, you know, he had to travel by train.

PRINCE: Let me ask you a question. You all had just come through a horrendous experience of being in the Holocaust; you were in a slave labor camp, and Murry was in a number of camps. How did you go back to daily life together? How was his attitude? How did you adjust? How were you adjusting?

GUTTERMAN: It was hard. At the time not too many people were interested in the situation where we come. Oh, you mean to each other.

PRINCE: To each other, how did you get up every morning? And then you still had these thoughts and memories. You both lost all your family, or most of it.

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, yeah.

PRINCE: And how did you (OVERTALK) go about feeling alive?

GUTTERMAN: We were – we were sad. We were sad. We were saddened and being protected, from my childhood, you wouldn’t believe it. I mean, it’s…you know, I was, not having too many, too much family, I was just so overprotective that if a child got a cold or something, I was crying. And because I felt like I don’t have anyone, anybody. So it was very, very hard.

PRINCE: Was Murry sad too? I mean, did he show his sadness?

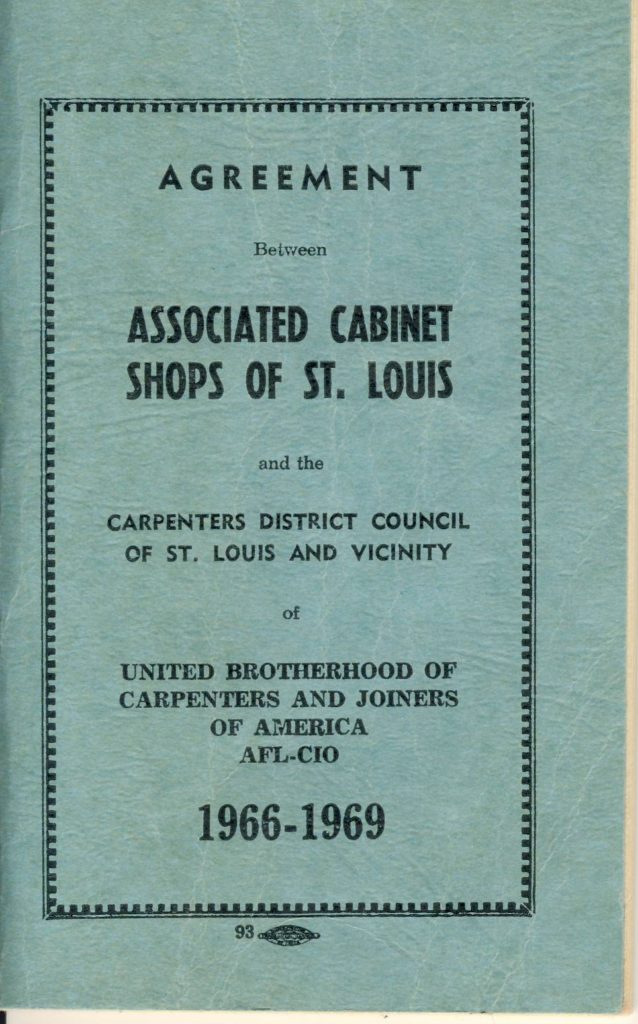

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, well he was more busy because he threw himself in, I thought, most of the time; even my children said he was working too hard. He just kept on working, even weekends. It’s unbelievable. And, you know, on vacation when we wanted to go, the only place we went is where we have a little family; that’s all where we went, to New York.

PRINCE: When you had your child – I mean, normally, when most people have children, “Oh look, he’s got so-and-so’s ears, and this one’s eyes, and this one’s mouth. And oh, he looks like my mother.” Did you all – were you able to say things like that?

GUTTERMAN: No, uh-uh.

PRINCE: You didn’t.

GUTTERMAN: We just could tell that they looked like their father or me.

PRINCE: Yeah, so you really –

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, but I know, even in my family, they know, that my middle daughter looks like me and like my father. But my oldest daughter, she looks like her father.

PRINCE: But – so you stayed away from talking about your family.

GUTTERMAN: Yeah. We talked a lot of times, only with survivors. But, a lot of times you talk to somebody, I think people don’t, didn’t know what to say. They felt uncomfortable. So I don’t think they were mean; they didn’t want to talk to you. I remember one time I met this lady and she said, “Oh, we had a really hard time here too. We couldn’t get beef,” and so on. So I didn’t think they were…very interested, or maybe they just, it was too hard for them to talk about it because, you know –

PRINCE: Well, it was hard for you all to have so much to get used to and then you have so much to be sad about.

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, it was very hard. And….so we again went to school. I went to Counsel House. They had a teacher there and…

PRINCE: Do you remember her name?

GUTTERMAN: No, I don’t remember her name. Isn’t that bad?

PRINCE: No, it’s just that I have a –

GUTTERMAN: I remember we had to write a paper and what I said, you know. And, I was just – we threw ourselves in, me and Murry, to learn English. That’s important, to read, and to write, because we just didn’t feel like a, uh, outsider. Unlike here, the people want to present nowadays their language where they came from. But, in my case, I thought we can do both.

PRINCE: Exactly.

GUTTERMAN: But, if you don’t know how to read or write…I used to – just when I was younger – I did that, put a book under my pillow here in the United States, before I went, when I went to school, and I read it when everybody was asleep. And some people tell me, “How come you didn’t teach another language to your children?” And I think, “My goodness, I think maybe I am selfish.” (LAUGHTER) But I just wanted to talk to them English. How else would I learn how to do anything? I know when I open my mouth I have an accent, but at least, you know, uh –

PRINCE: You wanted to make your way…

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, yeah, yeah. But then later on I was dreaming of going, maybe take a course at Mizzou University, (University of Missouri) but I had a child already, and I didn’t work. So, I decided at one time – we lived at this place – and I decided to, we had like – it was a ranch home, and the reason we weren’t helped by the Jewish Family (and Children’s Service), is that my husband went to work, because he got paid right away. So we didn’t get any help. So we rented a place. It was a family – they had a ranch house and they lived across the street. I’m still friends with them. And – but it was a – I just had one child – and (the house), it was too big. So I took in a lady with a little girl; she was two years older than mine. And I just cooked meals for her and took care of my little girl and her little girl.

PRINCE: So you made some money.

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, so I made some extra money.