SAMUEL: My name is Sam Riezman, and in World War II, I was in Europe as an assistant signal operations officer for the 17th Signal Operations Battalion with the rank of Captain. We operated the communications for the 1st Army Headquarters, and there were three of us who handled the operation, maintenance, and installation of the communications as the 1st Army Headquarters moved from location to location during the progress across Europe. As a result, one of the three of us Captains was always involved in scouting out new locations and the next location that the Headquarters was going to be in. That is just a background.

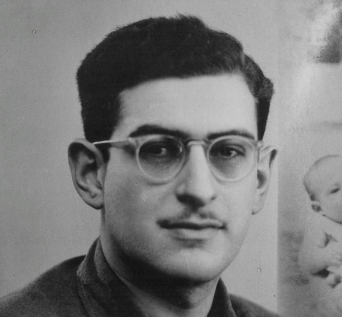

My experience with Buchenwald came about in the following way. We were moving in to Weimar, and for some reason, I don’t recall the details, but I went up to Weimar to investigate where we would move in to for the operation of our message center. One of our lieutenants, who operated the radio relay system, told me that the Buchenwald Concentration Camp was nearby and had just been taken by American Forces. So my driver and I, following his directions, drove over to the camp. At this time, I was twenty- four years old, and this was some time, I believe, in April of 1945.

I had expected to see something, but not really what I saw. As a result of being that young, I don’t remember too much of the details. However, I remember as we approached the camp you could smell the stench. I smelled something like calcium. It took your breath away, and was very strong. As we drove right up to the camp, there seemed to be an open area, and then beyond that, there were two posts, sort of an entrance in to the camp. The fence went on both sides. When we got there, someone, I believe the inmates, had hung an effigy over the center of the gate. I can remember, that hanging up there, and I think it was supposed to represent a guard.

We dismounted, and there were quite a few ambulances there, I remember. There were a number of American soldiers, and it was quite crowded. We wandered around a little bit, and it seems to me on the left side, off to a little distance, we found some ovens, and then, alongside the ovens were a couple of wagons loaded with dead people. They were naked and just thrown on the wagons. On the right hand side, as you came in, were the barracks and we went through several of the barracks that looked like they had been cleaned up.

The one outstanding thing I remember about the incident was talking to one of the inmates. He appeared to be a young boy, and in size and appearance looked to be about ten years old. I was able to speak some Jewish and he spoke Jewish. I talked to him and found out he was twenty-one years old. His growth had been stunted because he had been in concentration camps.

We also noticed that a lot of the inmates would not leave their barracks. They just would not go anywhere or do anything. It seemed that most of the young ones were willing to walk around, move around, and talk to the American soldiers. We were rather busy, so I think we spent probably about two and one half to three hours there. That’s all.

DAVID: That was your only experience with Buchenwald?

SAMUEL: Correct.

DAVID: What did you know about Buchenwald before you went there? Had you been told about it?

SAMUEL: No, I knew nothing about it.

DAVID: You had no knowledge that such concentration camps existed?

SAMUEL: Oh, I had heard rumors of concentration camps. But I didn’t know any of the names. The one we had heard of, I think, was Dachau, and I had been overseas for a year, and we didn’t get too much information of that type. Most of what we got was from Stars and Stripes and before going overseas I had heard some talk in this country about concentration camps. What we really knew was that there were oppressions of the Jews, and other people, but I was not really aware of the fact they were actually killing people and cremating them.

DAVID: So you knew nothing about the gas chambers and the horror stories like that?

SAMUEL: No, I did not. We saw them in Buchenwald. They did have a …next to the ovens, was a building with the shower. I guess it was supposed to be a shower, but it had a bunch of hooks on one wall. We never did figure out what they were for.

DAVID: What was your reaction upon seeing all this? What thoughts went through your mind and how did you feel?

SAMUEL: I became very angry, extremely angry, and I still am to this day. I can’t buy or anything from Germany. Another thing, too, in the positions I was in, I had a lot of contact with German civilians because we were using the German telephone system and that was the switching stations and that repeaters were located in Post Offices and cities. And as a result of that, I was exposed to the German civilians who ran these installations and we were using there. Using my Jewish, which was close enough to German, I was able to converse with them, and using some English and a few words of French, I could get my questions and instructions across to them.

Without fail, when I asked any of them if they had seen a concentration camp, they said no. They had never seen one of heard of one I can remember in Weimar, the man who was in charge of that switching station, that telephone system, never heard of Buchenwald, never, as a concentration camp. He didn’t know anything about it, because I talked to him about it.

We were in Weimar for a short time, and then the war ended, and we were transferred to the 9th Army and moved up to Brunzwick, Germany. There I ran into another interesting thing. This is getting off the subject of Buchenwald, but it is something else.

We were sent up to Brunswick, Germany to take over the operations of communications for the 9th Army. The first Army was to move out to the Far East. We were to join the 9th Army as part of the occupation and then after time we were also supposed to go to the Far East to rejoin the 1st Army. So we moved up to Brunswick, and at that time the other two captains who had been operations officers were sent out on an advanced party with First Army Headquarters and I became the chief operations officer. So I went up to Brunswick Germany first and found the location we were supposed to set up for our bivouac, for our tents and everything. We were located in sort of a wide, open grassy area, and right next to this area there was a hill, and on the other side were some wooden buildings. We wandered around in the wooden buildings and they were inside of a fence. It was like a compound.

In talking to some of the Germans, who were around, we found out these were work camps, and we actually found a lot of the pieces and parts there. I don’t know where the people came from but we were told they were paid people that were brought there by the S.S and put in these buildings to work. They assembled various types of telescopes and binoculars and scopes- aiming scopes for rifles. That was all slave labor, and from, we assumed, concentration camps, because we saw some of the striped uniforms that the inmates from Buchenwald had worn.

There again, in talking to some of the Germans with whom I had contact, they used to picnic out on that hill on warm afternoons in summertime. They had never even known this work camp was being operated by slave labor or people from concentration camps. None of them would ever admit to any knowledge of this.

DAVID: Do you believe the stories by some of the German people you met that they had no knowledge of these concentration camps?

SAMUEL: No, it was impossible for them not to have knowledge. Because we found out, and I don’t remember where, and the Germans were picnicking on the hillside within a half mile of it and obviously they could see what was going on. They knew the camp was there, it had to mean something to them and I’m certain they would have been curious enough to find out. No, I don’t think that was a valid excuse at all.

DAVID: You said that you could smell the dead bodies from far away. Do you think that the local citizenry of the village of Buchenwald would have smelled it?

SAMUEL: Oh, absolutely, they had to. It wasn’t so much the stench of dead bodies, but it was as though you were to burn calcium, if you know what that’s like. As if you were to take bones and grind them up and burn them. It was that kind of odor. It was extremely strong. There was no way not to know. There was no way not to know. These ovens had not been operation for several days when we got there, and you could still smell this odor all over the area. I’d say, at least within a half mile of the place. We could smell it long before we saw it.

DAVID: When you walked through Buchenwald, did you see an evidence of torture or mistreatment of the prisoners aside from the ovens and crematoriums?

SAMUEL: No, except from just looking at the inmates. They were pitiful in appearance; weak, starved, beaten. You could tell they had been beaten. Some of them had an eye out. They all looked very bad…very bad. You could tell from their actions and spirit, they had been thoroughly beaten or something, because they were afraid of anything and everything.

DAVID: Why do you think many of the prisoners did not want to leave the barracks?

SAMUEL: I think they had been there long enough to be afraid to move and I think they were afraid to move for fear they would be executed or beaten.

DAVID: You think they did not trust the American liberators?

SAMUEL: I don’t think they were able to think. That was one of my reactions. I felt that all of their humanity, all of their spirit, was gone. I read since then and I’ve realized that a lot of people, in that condition, did recuperate, but at that time, I did not see how it was possible, from looking at the people and talking to the people.

DAVID: Was there a special American group there at that time who were trying to administer them health and food and trying to help them?

SAMUEL: There seemed to be someone in charge, but I don’t know what organization or who, however. There were a number of ambulances. I would say at least six or eight ambulances. I assume there was a hospital of some kind in the area.

DAVID: Did you have any conversation with any of the prisoners besides this twenty-one year old?

SAMUEL: I tried, but he was the only one that would speak any sustained conversation. A few of them when we offered them a cigarette or some…that’s right, there was someone there that told us, “Do not give them any food or chocolate or anything rich because they would get violently ill.”

So evidently they had already discovered that. So we had to be cautious about what we gave them, and we were told it was all right to give them a cigarette or something like that. It was difficult to get them to say anything. But this one young man, I knew his name but I have long since forgotten it, he was the one who was willing to talk to me, and we did carry on a conversation. He told me he had been beaten many times and he was lucky to be alive. But evidently he still had some personality, and you could see that he, at one time, had been a very sharp young man. Evidently, he stayed alive by being sharp.

DAVID: Were there many prisoners who looked thrilled and excited by the fact they had been liberated?

SAMUEL: No, I didn’t see any. That may have happened on the first day or when they were liberated, but practically all of them I saw were very lethargic, not moving around much. They didn’t seem to be able to think of do anything much for themselves.

DAVID: I see. What was the reaction of the non- Jewish Army personnel there that you talked to about what you had seen after you had been through it?

SAMUEL: Well, I can tell you best about my driver. He was of Mexican decent. He was from Texas, as most of our battalion was. He shrugged his shoulders when I mentioned it and didn’t say very much at all. I mean he just took it for granted, didn’t seem to be upset, didn’t seem to be fazed by it at all, he just took it in stride.

I couldn’t. And eventually, when we got the battalion back together, and I mentioned that I had been there…we did have another Jewish officer in the battalion, he was our supply officer; he was a fellow named Miller from New York and I think he went to see Buchenwald, too, a day or so later. He came back and he was extremely upset about it, but no one else in the battalion seemed to be overly concerned.

Of course, you have to remember we had gone through almost a year of warfare, and while we weren’t in the direct action, we had been through quite a bit. Our battalion went through the Battle of the Bulge, all through that so we had lost some people and that had a certain amount of effect. Being in the battle zone for a year, some of these people had been out of the United States for a year, some of these people had been out of the United States for over three years. I was a latecomer to the battalion. They were a lot more callous, I guess, than I was, but of course the people we saw at Buchenwald were Jewish. I didn’t see any people who were not Jewish. If there were any, I don’t know.

DAVID: Any prisoners?

SAMUEL: Any prisoners that were not Jewish, I don’t know about. The ones I spoke to all seemed to be Jewish, and that could have had an effect.

DAVID: You mean an effect, that because the military personnel were Gentile, they were not so upset about it?

SAMUEL: I would say it didn’t hit home with them as much as those of us who wer Jewish.

DAVID: Since the experience is over, what effect on your life did it have after seeing the concentration camp?

SAMUEL: Well it made me realize that the history of the Jews had been the same repeated over and over again. My parents told me about the pogroms in Russia, and this was the same thing, except it was really organized on a full scale, efficiently. Otherwise, the effect it has is that I’ll always hate the Germans until I die. I blame the people of Germany. I feel that they knew about it, it could have been stopped, and they did nothing. I think they profited from it, I think people in business got businesses that were owned by Jews and I think there was enough of that being done that the German people of that time knew what was going on and should not have permitted it. I feel that it could not happen in the United States, hopefully, but I think you have an effect on me if something were to start in the United States.

DAVID: Did you see any Germans who were local citizens touring Buchenwald the same time you were there?

SAMUEL: No, there were no Germans around there ever, I was told. While I was there, there were no civilians of any kind.

DAVID: Knowing the way the German telephone equipment was installed, were the German telephone installers or telephone people that you were acquainted with, would they have gone to Buchenwald or around Buchenwald to install the communication equipment?

SAMUEL: There were telephones in Buchenwald. Saw the wires so I know there were telephones and I’m sure they had to be installed. I’m sure they had to be serviced and maintained and I’m sure someone had to go do it, and it had to be the people I was dealing with.

DAVID: Yet all of them said that they knew nothing about it?

SAMUEL: Never heard of the camp. Never heard of the Buchenwald concentration camp. No.

DAVID: Did you see the village of Buchenwald?

SAMUEL: I don’t remember it, we had rather explicit instructions on how to get to the camp, so we went directly to the camp. It was over some back roads. I remember we were in a forest and came around a turn, and we saw the camp.

DAVID: Did many of the U.S. soldiers who happened to be in the area come to see it out of curiosity, or mostly Jewish soldiers?

SAMUEL: No, I think many soldiers who heard about it came to see it, yes. I think there were quite a few soldiers there who were not Jewish. How they were affected, I don’t know. I don’t remember talking to any of them in detail, just passing comments, like “I can’t believe any one would do this”, or “This is horrible.” Nothing in detail.

DAVID: As you look back upon your visit to Buchenwald what about it stands out in your mind?

SAMUEL: The idea that it would have happened. It’s hard to believe it until you’ve seen it. The thought of it still affects me.

DAVID: Do you know how many prison inmates there were that survived at the time?

SAMUEL: No, I don’t. I remember there was a long row of barracks and we walked through several of them. I wouldn’t be able to guess at what size they were, but as I recall, they were set up like about 4 or 5 places to sleep in, one above the other. I guess if the place was fully occupied it would have been a tremendous amount of people. But we did not go through the entire camp. My driver was with me, but we did not go through the entire camp.

DAVID: Why didn’t you?

SAMUEL: We didn’t have too much time. It was difficult to know where everything was, and I had seen enough of what I thought was important- the ovens, the barracks, that other building; I don’t know what it was, I guess like a shower. I saw enough dead bodies. That was enough. I was upset enough.

DAVID: What were the thoughts and feelings that went through your mind as you went back to your home base?

SAMUEL: I had a feeling of outrage. I was outraged that something like this could happen, that things like this could be done to human beings. The people that were in the camp were pitiful. They were hardly human beings anymore.

DAVID: When you went back to your unit, did you discuss what you saw with your fellow soldiers, and what was their feeling about it?

SAMUEL: Yes. They most of them, had not seen it, and I’m not sure they ever did see it. They took it like anyone else would who hadn’t seen it. They believed what I said, but it didn’t affect them too deeply. Of course, Miller went to look at it, and he was, I think, just as much upset and outraged by it as I was. But we were there for only a short time and moved on, so we didn’t get an opportunity to go back afterwards.

DAVID: What type of age, nationality, and sex were the prisoners? Were they all men?

SAMUEL: I saw only men, I did not see any women but there were some dead woman among the bodies…there were women. But I guess I didn’t get into the part of the camp where the women were.

DAVID: Do you know what nationality any of them were?

SAMUEL: No. I don’t recall. The young man I spoke with, I don’t remember where he said he was from.

DAVID: The relief assistance that was being extended, do you remember who the group was and what they were doing for the prisoners besides the fact there were doing for the prisoners besides the fact there were ambulances there?

SAMUEL: There were some people, I think they were mostly U.S. Army enlisted men, and there were just several of them around who were going around making sure that no one disturbed the inmates too much and gave them instructions on what not to give the people. There were in addition to the medical personnel there, where they were from, I don’t know.

DAVID: Did they give you any instructions besides what not to give them to eat?

SAMUEL: No, there were no instructions as to not to go in or not to do this or not to do that, no. Just instruction insofar as giving them anything, or trying to get them to do anything, not to frighten them, things of that nature. That’s all. It wasn’t on a very formal basis. I don’t know whether this was organized or not. I think the camp had just been liberated the day before, or possibly that night before the morning we were there, I’m not sure. It wasn’t really organized. There didn’t seem to be any group running the show, so to speak. It was very haphazard.

DAVID: Did you have any other conversations with any of the inmates besides this 21 year old?

SAMUEL: No, None of the others would keep up a conversation at all that I spoke to. A word or two, and that was it…very little response from them.

DAVID: Were there any inmates that perhaps had been there for a short time and physically looked to be in fairly good shape?

SAMUEL: I did not see anyone. They were all very very thin- painfully thin. Just like bones. I assume they must have gotten away or left the camp when the Germans left.

DAVID: Had you heard stories about under what circumstances that ht e Germans left? Did they just get up and leave everyone there?

SAMUEL: No I remember asking this 21 year old, “Where did the Germans go?” And he said “Poof” or something like that. So from that, I assume they just took off.

DAVID: I see.

SAMUEL: But at that time to realize what was going in Germany, the Germans were surrendering very rapidly, we were not even taking prisoners then, we would just tell them to go home, and sometimes we would take their weapons. Other times just would not even bother. They were just surrendering very much in mass to avoid being taken by the Russians. We were getting close to the area that the Russians were coming into. So, it wasn’t at all unusual to see the Germans run and leave. In fact, I remember in Weimar you could see as many German soldiers on the street as American soldiers. They were just wandering around.

DAVID: …in uniform?

SAMUEL: In uniform, sometimes carrying guns. No one would take them prisoner, just tell them ‘ Go back to the prison camp.’ They kept going. Things were moving rather rapidly at the time, most of the resistance in Germany was gone. This was early in April.

SAMUEL: Do you have any memorables such as pictures, photographs, or maps, or letters or anything that has to do with concentration camps?

DAVID : I did have some pictures that I took using a German camera which I lost. I brought the pictures back to this country and had them for a number of years and somewhere in one of our moves they had gotten misplaces around here.

SAMUEL: Did you see a lot of other people there that were taking pictures?

DAVID: Oh yes, there were a lot of people taking pictures there. But I had one of these plate cameras, four by five, and I took quite a few pictures. I had pictures of the shower rooms, the ovens, the bodies, and some of the barracks. And I had a picture of that view of the front with the effigy hanging them. On this young man, too.

SAMUEL: Did the effigy have a German uniform on?

DAVID: No. It just had some clothes on. In fact, I think they were striped clothes because they didn’t have anything else to hand up there.

SAMUEL: Did the ovens have any remnants of bones in them or had they been cleaned out?

DAVID: No, they hadn’t been cleaned, there was something in them, small pieces of what looked like bones… yes, cinders, ash. That’s what was most upsetting to realize that those were people not too long ago.

SAMUEL: Did you have any conversations with German people in your stay in Germany to discuss what they’re feelings about it were?

DAVID: I could never find a German that would admit to know about it. No, I stayed in Germany until, it must have been near the middle of June from the time I saw Buchenwald until the time I left, around the middle of June, I had contact again with German civilians, primarily through contacts from use of the telephone cable, telephone system. I was unable to ever get, anyone any German to admit that he knew about a concentration camp.

SAMUEL: Even if they said, that they didn’t know about it, did any of them express any feelings about it?

DAVID: No, they just said they did not know anything about that. They had never heard of it. That’s it. They would not admit to having any feelings about it. It was just something that didn’t exist, period. Of course, most of them were not Nazi’s any more, either! So, the two things go hand in hand.

SAMUEL: Did you have any conversation with Germans that knew you were Jewish?

DAVID: I am not sure if they knew I was Jewish or not. I would assume they could tell by the accent when I tried to speak German, but the fact of my being Jewish or not Jewish, I don’t think that. I don’t think that was taken… although I guess at the end I would use that as a threat, I guess when we weren’t able to get things don’t that we wanted done. I would talk to someone and say, “Look, I’ll do what you did to the Jews if you don’t get this done.” I don’t know that it ever did anything. That was just for a short time. But truly, I did speak to many Germans, and never got any admission of knowledge of the concentration camps among the people I spoke to.

SAMUEL: Even though, naturally, as you said, the people who installed the telephones…

DAVID: It wasn’t only the telephones. You see, the telephones were in the post office, so the people I was dealing with were in the Postal Service and the telephone service. Anybody would know about a concentration camp where you were going to get mail. Even of it wasn’t for the inmates, it was certainly mail for the Commandant and his staff. And telephones, they had, so they had to know about the existence of it yet they would not admit to knowing about it. “Oh yes, there was an army camp,” I recall one of them saying. He never heard of a concentration camp.

SAMUEL: Looking back on it, are there any other feelings or thoughts you feel are meaningful about it?

DAVID: No. I think the publicity has done as much for bringing it to the attention of the world but unfortunately, I don’t think it can be felt as deeply by people who have not seen it. The pictures are very graphic and everything else, but being there, seeing it, feeling it, and smelling it makes a difference. It’s horrible beyond belief.

SAMUEL: You felt intense anger as you left.

DAVID: Yes. Oh, I still do. I still have a phobia about anything German. My son has a Volkswagen in Europe and I am uncomfortable getting into it and I will not buy anything that’s made in Germany, whether it is East Germany or West Germany. I will not have anything to do with it.

SAMUEL: Thank you very much.