TENZYTHOFF: Where were they going. The answer was, by way of Oldenzaal. I knew that part of the country inside out and recognized, even though it was dark, it was moonlit enough for us to – we are talking about May of 1943 – to see where we were and pretty soon it was clear to me that we were being taken into Germany. Again, I tried to find a way to let myself drop off that train but failed on that one.

Now, prior to being boarded on that train at Ommen, we were not interrogated in the sense that each one was given a long interview. We were simply to appear for a number of officials in German uniforms who would check our ausweiss, our identity papers, and so forth. And this one man said, “Ah yes, tenZythoff.” He wanted to know about where my parents lived. What could I say? The address was right on there and he said, “And how are your Jewish friends?” I said, “What Jewish friends?” By this time I had lost my respect for authority, and I had no qualms anymore about telling lies. Before that time, that bothered me. “Oh,” he said, “we will find out.”

PRINCE: This was a German, not a Dutch…

TENZYTHOFF: Yes, it was not a Dutchman. We will find out. The – that happened then in Berlin.

PRINCE: You were in Berlin?

TENZYTHOFF: Yes, that’s where we were brought – all the way up to Berlin. That’s where we were herded in some camp in which there were an awful lot of people. It was kind of a holding camp in which it was not a concentration camp in the sense that this was your final destination. It was a Arbeits-lager, as the Germans would say, a holding facility from where you were farmed out then here, then there.

PRINCE: Do you remember the name?

TENZYTHOFF: No. I only know that it was located on the Wannsee. That lake was clearly nearby. That’s the only thing that I can recall. Because from there I was brought to what was then the Alexander Platz. And that’s where I was asked the question, “What do you – what can you tell us about your Jewish friends.” And it is there that the interrogation took place and where I denied such connections.

PRINCE: How did you feel?

TENZYTHOFF: Determined not to say anything…

PRINCE: You were so young –

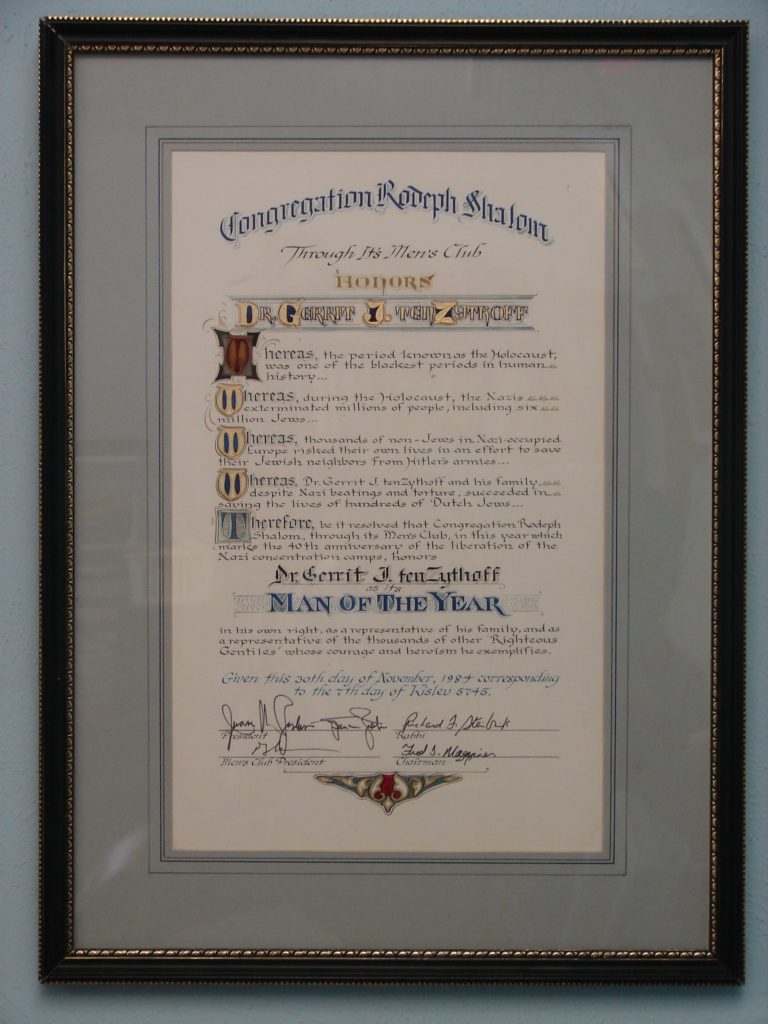

TENZYTHOFF: And scared. But, what is fear and courage. I think that courage is only the management of fear. That’s what I have concluded. If you can manage your fears, you have courage. I didn’t have any kind of bravour because it hurt. And one of the things that happened to me was that two of them took me under the arm and slammed my head against a wall like that. That’s what did the damage to my neck although it didn’t show up until later. They broke some of the cartilage that finally worked its way into the spine. And that showed up in 1969. That is when I had to undergo these delicate operations.

PRINCE: So that’s the physical price?

TENZYTHOFF: That was the physical price I paid, although I did thank the Almighty on many an occasion for letting me come out scot-free and whole. The interrogation didn’t last very long, as I recall, about three days. It is then that I was taken to a work camp. Don’t ask me why because I don’t know. Nobody – I’ve never been able to find that out. In fact, I was not interested in finding out. All I was interested in to – then to escape from this rotten business because where we now were was a camp in the eastern part of Berlin. In ’83 I tried to look it up once more and I surely got to it except there is nothing left of it. These East Germans have built all kinds of apartment houses there. The only thing that I recall as a memento is a church that was there and that stands there as a witness to the battle of Berlin. They left that one standing. Also, we were marched at six in the morning to the Knorr Bremse, which is a factory of railway brakeshoes. It is what Westinghouse did for railroads here making that braking system. But, of course, that is not what they were making only. They were also making U-boats and tank parts, and so forth, and that’s where we were told we would now participate in the production process. And I was given four big machines and I was to attach parts to that and then press a button and then the thing was supposed to work. Well, I certainly wasn’t planning to – with my own hands – fabricate the stuff that would stop my liberation. Therefore, I collected some sand in the camp where I was being held and put that in my pocket, and instead of oiling the machine, as I was told I had to do, and you know, what little understanding did I have of that stuff, I managed to pour that sand into one of those machines which, as long as I was there, never worked again. But, you know that meant that only one was out of commission but three to go.

PRINCE: Didn’t they follow up on…

TENZYTHOFF: Yes, they did. But then I doubt that they ever suspected that somebody (LAUGHTER) would really try to do that to them on their home turf, or whatever. And I was bound and determined to say, “Look, I’m here only from six to six; what happens here after six p.m. and before six a.m., how am I supposed to know?” Well, that is part of that spirit of sabotage – there were a lot of Russians there. They were marked with the sign “OST”, East, and the Russians called themselves Organisation Stalin. (LAUGHTER) You know. If we were not treated very well, they were treated like beasts. That was terrible. We were separate although the camp – there was a connection and from time to time we would make our ways in there. We didn’t have much to eat but at least we had more than the Russians and we would share some with them, poor fellows. We would refuse to talk German. The Russians didn’t talk Dutch. I didn’t talk Russian, so we conversed in French. That’s what they understood, but not very often.

My aim remained, “How do I get myself out of here.” And that came as the result of World War II’s R.A.F. bombing raids on Berlin. I survived two of them. The second one hit the camp, but I survived. And that’s when I walked out.

PRINCE: Free?

TENZYTHOFF: Yes, and made it all the way back to Holland. That was done because, fortunately, I have to go back a minute to the high school – one of my earlier acts of opposition to the Nazis was to flunk German. I was very proud of that until I got home and said to my parents, “Look, I flunked German.” (LAUGHTER) My father said, “Oh, I see. I’ll talk to you later.” It meant – I knew what that meant.

PRINCE: What did it mean?

TENZYTHOFF: It meant that later he talked with me and said, “Son, you need to think about this again.” I was not about to. So, he said, “Son, I need to reason with you.” He said, “Look, as you are, I am convinced that Hitler will lose this war.” Now remember this is ’42. The Americans are not in it yet. “The Germans are going to lose. Once we win,” he said, “we have to rebuild Europe.” He said, “Not knowing the language, how are you going to converse with people who have to be re-educated?”

PRINCE: So you buckled down and…

TENZYTHOFF: I compromised. On a grade of 10, zero to 10; zero to flunk and 10 the highest, I made a six because under that –

PRINCE: But you did know some German.

TENZYTHOFF: And, I must say my dad was right because – only because I knew German could I escape. That’s because – no arms, no identification paper. I had smuggled rubber – rubber sheets tied around my body out of the factory and sold them to the guards to get some money – to get some cigarettes because that was better than anything else. The – I had enough money to buy railroad tickets on the railroad and I traveled together with a camp mate, Aart Blauwendraad, also a student, and Art and I, although I’ve talked with him after the war twice, but he – his life has taken a kind of another turn and we have not really become strong friends. Although when I get to Holland, I make an effort to at least call him and see him. I don’t exactly know why not. But my life took a different turn, as did his. It was mandatory to be together for us, because we knew of the stories that were being told that you could have that terrible letdown and being overcome by fear – which happened once to him and once to me. You are ready then to turn yourself in and to spill everything you know because you get so frightened. It’s what the secret police always wait for because that’s when it is easy for them to get the full story. By being together, it meant that we were able to help each other over that hump.

PRINCE: When one is up the other is down.

TENZYTHOFF: That’s correct. If it happened at the same time, of course, we would have been a sorry pair. We had figured out that – he and I had talked about that only very briefly – he and I shared the same barrack, not the same bunk. And – but he said, “Gerrit,” he said, “do you want to stay here?” I said, “No.” “Do you ever think about going back home?” I said, “Yes, I do, constantly.” He said, “So do I.” He said, “Maybe there will be an opportunity.” I said, “Yes, maybe, this camp is going to be hit one day.” And, sure enough it was. It was then that everything was in disarray. The guards were no longer interested in you. They had gone home to check how mama was and it was a general mess and nobody thought about trying to escape. But we knew exactly where to go because we had inquired from German supervisors where in Berlin were we, and where was everything located, etc., etc. And, sure enough, they told us about the Anhalter Bahnhof, railway station. I knew that in general, and thank God for geography lessons which I hated at the time and there was this blank map with nothing on it in front of the class and we had to fill in where is Berlin located? Where is Amsterdam? That’s easy, isn’t it? Where is Leipzig, where is Warsaw? I knew that by heart and if you traveled by rail from Moscow to Amsterdam, how do you go? What are the important lines, and so forth. I knew them by heart. I blessed that teacher that I hated so much, (LAUGHTER BY BOTH) at the time, including my own father.

PRINCE: Uncanny!

TENZYTHOFF: And I also thanked my dad and mom many a time although privately because they simply were not around, God, if I hadn’t known German, because this is the way we did it: we walked up to – we knew that fast trains, the D-Zuge, were being checked all the time. We knew that locals were checked far less. And so, Art and I did not travel together in the sense that we would march up together in step, and so forth. We kept our distance from each other but always knew where the other was. We didn’t go to the toilet together, and so forth, so that we never would attract any kind of attention. But we walked up to the ticket office equipped with what we had done at the newsstand. We had bought, God forgive us, such things as Goebbel’s weekly “Das Reich” and including Julius Streicher’s “Der Angriff.”

PRINCE: Sturmer?

TENZYTHOFF: And “Der Sturmer,” and so forth, but the Angriff, that was his rotten antisemitic one, and having that in your arm, putting that down right in front of the window and then asking for, “Fahrkarte” and not even say “Bitte.”

PRINCE: What is it?

TENZYTHOFF: A fahrkarte is a ticket on the train. And then we wouldn’t buy that to a far destination. We would buy it to somewhere like to Magdeburg. (OVERTALK) And we would travel on slow trains and we would say “Heil Hitler.” That’s how we bluffed our way through.

PRINCE: That’s amazing.

TENZYTHOFF: Yes. We didn’t eat anywhere.

PRINCE: You were so young.

TENZYTHOFF: But we were infected by the war and we had figured out – Aart on his own and I on my own – that certain compromises risked former standards, such as always telling the truth, had to be abandoned if you were going to make it. And we did. In other words, one address to which it was safe for us to go – I’ll show you on the map where it is. It’s a German farmer who lived here. See where it says Meppen? We took the train as far as Meppen….

PRINCE: In Germany?

TENZYTHOFF: Yes. Then walked the last, I would say about 15 to 20 miles to this part of the border because here is a small village of Fehnsdorf where there lived a Dutch farmer who was a Nazi of record but through whose farm many a Jew and others reached Holland.

PRINCE: Oh, so he just said he was a Nazi.

TENZYTHOFF: Yes. He emigrated after the war. I tried to look him up. When the villagers found out who he really was, it was better for him to leave. He went to Canada, but there he died.

PRINCE: Oh.

TENZYTHOFF: Yep. But we – I’d never been there before…

PRINCE: Before I forget, I have to ask you this – This was – this resistance was underground that your father was part of (OVERTALK) the family, the doctor.

TENZYTHOFF: Belinfante.

PRINCE: Yes, you always – you never forget him.

TENZYTHOFF: No, no.

PRINCE: Did it have a name?

TENZYTHOFF: No.

PRINCE: You were not part of a…

TENZYTHOFF: Yes, there is a Landelyke Organisatie, National Organization to Help Those In Hiding, yes that’s it, The KP or Knockploegen (Hit Squads) for armed resistance. Onderduikers are those who live underground. That’s the most general statement that you can have.

PRINCE: Alright.

TENZYTHOFF: There is a committee. That’s that’s – we were closest to them.

PRINCE: Closest to them in what way? In what you did?

TENZYTHOFF: Jah, and similar.

PRINCE: But not part of them.

TENZYTHOFF: No, no, not officially.

PRINCE: So…

TENZYTHOFF: Because my dad studiously avoided any official leadership role. That is, he had his own network and he worked it on his own. He never had anybody order him what to do, because that’s the one thing that he could not carry out, no matter how much he had wanted that, because he had to keep that school going, he felt. His only other choice would have been “I go hook, line and sinker,” at which point he would have had to abandon his family and risk that.

PRINCE: I didn’t want to get you off the track…

TENZYTHOFF: I’m so glad you do.

PRINCE: …but I wanted to ask it, because on the map you’re way up here…

TENZYTHOFF: That’s correct.

PRINCE: And I wondered – obviously this has widened out now and spread…

TENZYTHOFF: Oh yes, oh yes.

PRINCE: …so that’s why I wondered if it had become more of a – obviously it was larger – but organ…it was organized but…

TENZYTHOFF: It was organized…

PRINCE: …in its own way.

TENZYTHOFF: In its own way. It was organized in this fashion that you hardly knew what the next fellow did. We knew of the existence of this man but we…

PRINCE: But he may have not known your father.

TENZYTHOFF: I’d never been there.

PRINCE: But he didn’t know your father – it was just a network.

TENZYTHOFF: You try to know as little as possible because they couldn’t make you talk if you didn’t know. You see, that is the one de – we had learned that, that the more you knew, the more dangerous it became, not only for you – that was one thing – but it became dangerous for others because there were methods by which they made you talk. The – it is he who brought us, not across the border, but to the border. And it was not only the same German occupation as it was, but boy the Germans certainly knew the difference between Germany and Holland. It was a wide strip, a no man’s land. It was guarded by watch towers with searchlights on it which they flipped on from time to time and it was guarded by police dogs that they would run from time to time. So, it wasn’t just a picnic to walk out of there, although I’m going to make it sound like it because literally nothing happened. This is peat country. They were still digging peat there for burning, heating purposes. All that is now gone because all the peat has been dug and the good earth has been so reconditioned that you see prosperous farms there. At that time they didn’t. But it was ideal for people like us who needed some shelter. This peat would come out very wet and it would be dried in the wind. Peat is that vegetation which turns into coal after thousands of years under the pressure of the soil.

PRINCE: I don’t want this question to sound trite…

TENZYTHOFF: No, go ahead.

PRINCE: …but you went through all of this for a moral…

TENZYTHOFF: Yes, that’s correct.

PRINCE: …act of not wanting to sign the paper.

TENZYTHOFF: Exactly. And, because I didn’t want to endanger my – to save my own life at the expense of somebody else. And my parents agreed. But, they full well knew, my father wrote every week a letter to the German commander of the area in which we lived right here at Arnheim and he would say, “According to the Geneva Convention, an occupying power is obliged, after they arrest one of the citizens to inform them where they are held.” Alright?

We got across the border and then we knew where we had to go – there was a pastor living in the midst of nowhere in this peat land on the Dutch side and by name of De Weert. I knew of him and I knew that that would be a safe address. That was the next station, and so we went to the first farm house that we saw in Holland. Now, there was a curfew on, from dawn to dusk. It was no longer daylight, it was now night, and the Dutch Nazi in Germany had alerted us that you better be aware of that and be very careful. He said, “And I count on it that you will never reveal my name,” which of course we didn’t, but we weren’t pressured either because neither one of us was ever caught again. The first farm that we came to, we knocked at the door because we really had to get our bearings. I didn’t quite know where we were and neither did Aart. So, we had said, “If he is going to turn us in, we’re going to beat him up and we’ll kill him.” Alright. When the door opened, the man said, the first thing he said is, “You fellows escaped from Germany, huh?” And we said, we said to him, “Well, what’s that to you?” He said, “Well then you need some help.” I said, “What kind of help?”

PRINCE: Could he tell by the way you were dressed…

TENZYTHOFF: No, he saw it in our eyes, and so forth.

PRINCE: ‘Cause you didn’t have to wear any kind of uniforms in the camps?

TENZYTHOFF: No, that’s right. The clothing was now brown, I was not walking on shoes – my shoes were gone so I had some sandals on, etc.

PRINCE: So, he knew.

TENZYTHOFF: But, he knew. Besides who would, at night, if he didn’t live there, travel around under curfew? Strangers in a – you know – in a not too densely populated area are always identified. And he said, “Well, do you need some help?” He said, “I’ll call my wife, she’s upstairs.” She came down and he said, “Good fellows, what do you need? Money? Food?” Neither one of us was hungry, we were thirsty. He said, “We will get you some milk.” We got a glass of milk, I could hardly drink it because I was very uptight. Remember, we were ready to kill the guy, if he turned out to be a Nazi. And if there was any indication of it, because having come so far, we were not about to give up. We asked him – I think Aart was the one who asked, “Sir, why are you helping us?” He said, “I want you to know that when the Germans invaded Holland, my son died in the defense of his country and I’m bound and determined to do as much harm to the bastards as I can.” He said, “And therefore, whatever it is, you just ask.” I said all we needed to have was the directions toward a church. He said, “A church?” “Yes, I think Pastor De Weert is its pastor,” Aart said, “if I’m there near that church then I know where to go.” He said, “Where do you want to go?” I said, “I would prefer not to tell you.” There was no way that I could avoid having to mention that Pastor De Weert, I wish that I wouldn’t have to, but then, he said, “Well that’s not all that difficult,” he said. “It’s quite a walk that takes you over an hour.” In fact, it took three. He said, “Be careful.” And then he gave us some expert directions and slowly but surely we made our way to Paster De Weert who took us in immediately. The first bath and the first bed to sleep in. The next day…

PRINCE: Dr. T., did you cry?

TENZYTHOFF: Not any more. I can say that I said for the first time since a long time another prayer. I’d become kind of an atheist at that point. But this I thought was rather miraculous.

Now what? We couldn’t stay there and didn’t want to. I thought, I can call my mother. There is a telephone and I know when to call and it’s about 10 o’clock, that’s when she has all her work done and sits down for coffee or whatever the substitute is. I’ll call. I did. I said, “Mother, this is your son, Gerrit, I’m at De Weert’s and I hope to see you.” Then I hung up. The next day my parents came. First thing my mother said was, “Son, you can’t come home.” I said, “Mom, I know.” So, we figured out a strategy and right there at Gramsbergen.

PRINCE: Where?

TENZYTHOFF: Gramsbergen where I was born. Remember how my father – that’s out of the way, right here, where the Vecht comes in to Holland. There was one family in contact with my parents. My father did them a good turn once, a very good turn. He discovered that one of their kids couldn’t read but was so smart that he could do anything from memory. That’s how no teacher had never discovered that he couldn’t read. He would make mistakes but he was certainly a “B” reader. My dad figured that he was too smart to just be a “B” reader and gave him the first turn and the boy said, “I don’t know how to say it.” Dad said, “That’s alright, son, I’ll talk to you after school.” And then he found out that the boy literally couldn’t read and resolved that for him which created on the part of the parents an enormous degree of gratitude – that was one of those. They became lifetime friends. Dad said, “Gerrit, the only place that I know which is not being used by others, Jews and other onderduikers (underground people) are the Wilpshaar family, and that’s where we’ll have to go. I didn’t consult them because there was no time for it. We will just go there and ask for advice.”

We got there, my dad and I, and when my father began to ask, “Could I ask a favor,” the farmer said to him, “Vraag maar niets.” The old man, I still see him standing there – he said, with tears in his voice, “You don’t have to tell me anything, I know what you want.” He said, “You’ve got it, he’s safe. You go home.” I’ll never forget that. And we have remained friends ever since. God Almighty, these people – there had been a razzia just a month before. The Germans had rounded up about 30 people, they had shot a few. The family had officially vowed, “We will never get involved again.” I only found out that story a half year later. These people were absolutely without fear. Their very neighbors never knew that I was there. This was the base. That’s where weapons were, that’s where the leader of this organization…

PRINCE: The one we were trying…

TENZYTHOFF: Yes, that’s right. The one – the organizer of the L.O, the Reverend Slomp, the leader was sprung from prison. That’s where they brought him, and so forth. Frits de Zwerver he was called. He was a Pastor who had dedicated his life to the hunted, and my father was deeply in awe of this man because he had risked his family for it, something that my father said, “I was at first not willing or able to do.”

PRINCE: But your whole family was part of this…

TENZYTHOFF: Yes, my sister would carry messages, my youngest brother would be kept in short pants so that nobody would suspect that he was already 15 or 16, and so forth, and he was small. It took him longer, by year 17 or 18, he grew up to be much taller. And, thank God for the people who don’t grow up all at once. And, he did a number of things at home that I am not entirely aware of because, again, I can not talk about ’43, ’44, and ’45 at home because there were…