PRINCE: I am “Sister” Prince and I am interviewing John Brawley. In 1944 Mr. Brawley landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, France on the Sixth of June 1944, D-Day. He was involved in the liberation of Nordhausen Concentration Camp.

Mr. Brawley, let’s begin with your rank, and in 1944 your involvement – the beginning of your involvement in D-Day. I believe you were in the Signal Corp.

BRAWLEY: Yes, I was in the Signal Corp and my first involvement with the D-Day, or with the invasion was in starting in England when the planning was started. Well when the planning had gotten below the highest level, the decisions of where we were going to land and things like that were made, and then the detailed planning is something that I got in on. Mine was Signal, and I was basically – my duty at that time – I was a First Lieutenant. My duty, classified duty, with the Signal Office was as Radio Officer but I also had a part in…I was designated by my Signal Officer, Colonel…Colonel Sawyer, to help make the plans, signal plans for D-Day. And so we went off down to the southern part of England to do this, down to Plymouth, where actually the…from Plymouth, Bristol, and some other ports on the southern coast of England is where the D-Day invasion was marshalled and where they took off on June fifth. My job was in writing the signal annex, that’s the signal part of the Seventh Corp, which was half of the U.S. involvement on D-Day of the invasion. There were two Corps that made up the U.S. part of the invasion. That was the Fifth Corp on Omaha Beach and Seventh Corp on Utah Beach. And then the British and the Canadians were to have left on three other beaches on D-Day. Now…

PRINCE: And the names of those beaches were Sword, Juno…

BRAWLEY: Sword, Juno and Gold…British and Canadians. We went from what they called the trout line on the right to the…don’t remember the name of the line at the other end of the beaches, or the landing area down the coast from where we landed. The Seventh Corp was on the extreme right, and nobody really knew what to expect on D-Day. We had the best intelligence information from the intelligence gathering people where it was available. On Omaha Beach they said you…there was a small training unit there and the poor Fifth Corp that went in on Omaha Beach found that there was a full division there and where we had kind of screwed up with the intelligence.

We expected, I think, we expected something to happen on the way over. I know we did…I did. You really didn’t worry about it, you thought…you didn’t know what was going to happen, but I guess you had confidence that whatever happened, you were going to be all right. But anyway, going across the Channel the night before, after all of the delays and the apprehensions and the indecisions, when Eisenhower finally gave the order saying, “We’ll go…okay we’ll go,” it was…the weather was very bad – it was really touch and go. The weather forecasters had predicted just a few hours on June Sixth, which would be a break in the weather and that’s when they went in. We were extremely lucky there. On the Seventh Corp itself, we were extremely lucky, in that, there were five causeways that went from the water’s edge across about 600 yards of beach, then the causeways took over and went in-land and they were the only access…there was a marsh…I couldn’t believe my eyes when I walked into the planning room, the super secret planning room down at Plymouth, England to see on the wall a map and to see the Seventh Corp which was Utah, or Utah Beach, was going to land through a marsh, of all places you know. But it probably helped us in the long run because the Germans may have figured…

PRINCE: Who would land there?

BRAWLEY: Yeah, who would be stupid enough to do that? So…but to make matters better or worse, we had planned to go in on the two causeways on the right of our sector – it’s about a mile long – the beach was – each beach was about a mile long…maybe a little more than that. And that’s the planned route. Well, when the first troops left the troop carriers, they were about 10 miles off shore to go in on landing craft…there was a slight wind blowing from right-to-left and one of the pilot boats got knocked out on the way in and the other one made a little mistake and they landed, because of this drift, they landed about a half a mile…maybe more than that…about a mile, yes, farther down to the left…to the east of where they intended to. And just by happen-stance, the two causeways that we were able to go in over had been heavily armed by the Germans and they had not been yet secured by the airport, or paratroopers who dropped in the night before and were scattered from hell to breakfast all up and down the peninsula, you know. It took them hours and hours to get assembled. So, the troops landed at the wrong place. And the big thing about beach landing is…get off the beach, get off the beach, get off the beach…that’s all we’d ever heard, you know, don’t stop on the beach, get off the beach. So they started in-land and they came to the causeway number two, that’s the first one they ran into which was the wrong one. And they had drawn up there and these were mostly Fourth Division Troops…that was the invasion troops were the Fourth Division. The Fourth Division and the First Division on Omaha…the Fourth Division on Utah provided the first waves of the first assualt. They’re up there…

PRINCE: Excuse me, did it happen simultaneously?

BRAWLEY: Yes, everybody in both Corps landed. The British and the Canadians. The time varied a little but both of them were 6:30 a.m. Preceding the landing there was an unbelievable bombardment of the beach and coastal area by the warships, you know. I stood outside about…and just before this, when daylight was breaking…

PRINCE: You were on the deck of…

BRAWLEY: I was on the Bayfield which was one of the ships…

PRINCE: Was it a destroyer?

BRAWLEY: No, it was a navy troop carrier really that had been converted. We had the radio room built…a steel room built on top deck and in there was where we had the radio equipment and in there was where General Collins was, pacing up and down in front of those radio receivers with General Barton, who was Fourth Division Commander, right behind him and right behind him was Colonel Sawyer, who was the Signal Officer, who is responsible you know, and I’m a few paces behind worrying if anything goes wrong…it’s my neck!

PRINCE: It’s your neck?

BRAWLEY: That’s right. And especially on radio because the radio contact was to be the first contact and General Collins was very nervous because he had tremendous responsibility. He was responsible for all of Seventh Corp which was half of the U.S. invasion and had to work, because not only would his reputation go down…he’d be a failure! And believe me, if you’re a failure, that’s the greatest motivator in the world, but he was…General Collins was, I must say, was one…not only one of the greatest Generals, but one of the greatest men that I’ve ever met…

PRINCE: Because?

BRAWLEY: Because he was smart enough to do what was right…he was trained at West Point to do what professionally needed to be done and he was what I called a “real General.” He was up-front all the time…he was where the action was…he could make a decision and he was a real General. And I hate to say this, but I contrast a real General as one contrasted with a paper General who has been promoted by shuffling papers and a lot of them have grown up since the war, you know, and have never really been “in it.” They were weeded out at the beginning of the invasion and the only people who really were the “top people” and had some experience, were in there. Anyway…

PRINCE: I just want to ask you one question.

BRAWLEY: Yes…

PRINCE: When you said contact – with your radio contact – that’s with the first people on the beach. Is that correct?

BRAWLEY: Well, let me explain it. We had the 101st Airborne Division and the 82nd Airborne Division were dropping paratroopers. They dropped at two o’clock in the morning and they were to drop behind the beach, all these causeways…both, or all five of them and secure them. And so our first radio contact would be to contact the paratroopers who had dropped and find out how they’re doing…if they’re securing the beach at the causeway entrances so we would have some knowledge of what to expect, you know, when we got ashore. Now…

PRINCE: What is a causeway?

BRAWLEY: A causeway is a road that’s built through a marsh of which we were attacking, and it’s a little road it’s very narrow…almost one way, and that was their job. Well now, our job with radio is to contact them and they knew…they had all the coordination that we could possibly work up. But we didn’t know that they’d been scattered up and down the coast in the drop and that they were even lucky to find each other and find themselves, you know, to get together and get to their equipment…and lots of it was dropped in the wrong place and their maps didn’t look right because the air force was eager to get out of there and just a few seconds could make a big difference in where you dropped. And so, they had a lot of work to do to get together, to get their equipment to contact.

In the meantime, General Collins is walking up and down in front of radios picking up things. I’ve got some of them here that was scribbled on that morning, which is really just scribbling…it’s nothing. (SHOWS NOTES) He’s pick one up and hand it to me, “Decode this,” you know. “Here’s a message”…There’s nothing on it. But I’m not going to tell the General that there’s anything wrong. So I take it over to the crypto officer and I’d say, “Decode this, Mr. Florence,” and he’d say…he’d look at me, you know, “You crazy?” So I’d say, “Just take it.” Then I’d go back in a minute and I’d say, “General, not yet.” (LAUGHTER) And then finally the first message came through. It wasn’t from the Airborne Division, it was from a little assault group that had attacked what we called the Iles St. Marcouf – just off the shore where they thought there was some guns, you know. And the message came back, “Mission accomplished.” It was the first message. It may have been the first message of the invasion, you know, because it was pretty early that morning. Well, now a lot of the stress and a lot of the anxiety was gone from General Collins. At least he got a message back. And pretty soon we began to monitor those radios of the airborne people, not in communication with headquarters yet, but talking to each other. But we’re only a few miles away so we could monitor and get an idea of what’s going on, and we knew there was some chaos.

But anyway, back to the Fourth Division when they got in. You see the bombardment lifted precisely on time, about three minutes before they were to hit the beach…the bombardment of the guns. And I didn’t mention the air force but there was a tremendous bombing of the beaches also. Except that, in their over-caution, they missed the beaches and bombed in back of them and devastated a lot of cows in the pastures and some Frenchmen, you know, in back of the beaches. The bombers – it was really not a success. It looked…I stood on the deck of the Bayfield and watched…now it’s getting daylight and I thought, “Well, the war’s over,” you know. What could possibly survive all the bombing of all those hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of bombers, and the shelling from those big warships, you know…

PRINCE: Excuse me, standing there, could you believe what you were really seeing?

BRAWLEY: No.

PRINCE: These ships, these men, these bombs…I mean…

BRAWLEY: It was…not yet, but I’ll tell you about what I really felt after getting to the beach, but it’s a little unreal even at that point, you know. I’d never seen a battleship and here it is, just daylight enough to see the battleship, and they started…all started exactly at the same time when it was scheduled to start…just a few minutes…no about 30 minutes, I guess, before the landing. And those big ships – just big smoke – the big noise when they fired. And they’re rolling in the water…the sea was very rough that morning you know. It had been a stormy night and it’s going up-and-down like this. (GESTURES) And a Navy Officer was standing with me there and I said, “How can they possibly hit anything…look how the guns are going up-and-down.” He says,“They’re timed to fire on the roll of the ship.” They were activated…the guns from the battleships and the cruisers and the destroyers, and we could see the destroyers getting…they looked like they were right at the coast, you know. They’re still a mile or so away. But of all the ships that we had on D-Day on the Seventh Corp, only one destroyer was sunk…one was hit by shore guns and sunk but the rest of the, you thought, you know, how can they – with all of this firing back and forth, it’s going to be more damage than that, but there wasn’t.

Now – after they’d lifted the guns, the bombardment, and after the air force had dropped their bombs, then it’s just a couple of minutes before the Fourth Division troops who are in the landing craft entry of the LCI’s just off the shore came in. And they’d come in to about 50 yards, I guess, of the beach and then drop the front ends down. Maybe you’re seen pictures of them – the front ramp just comes down and they – you’re off in waist-deep water because they can’t go in any further, you know, and they wade on in. Well – they got across the causeway too.

Now the Assistant Division Commander of the Fourth Division was General Theodore Roosevelt…the III, I guess. He was a real General too. And he was – I don’t know – he may have been 50 years old then, but he just went with the first wave, he landed, and he’d walk up and down with his cane and say, “Get off the beach men, you know, we’ve got to get off the beach. You’re going to get killed if you stay here…get off the beach.” So they’re all up at this causeway and then they discover that he’s at the wrong causeway and he had a decision to make, shall he go on across the causeway, they’re gotten across 600 yards of beach and they had really very few casualties because there’s not much defense down there…shall he go on across this causeway and have the troops that are following come across the causeway – or shall he go back to where they’re supposed to be! So that’s…I always say, that’s what the General is for – to make decisions. And he made it, he said, “Tell the navy to bring ‘em in…we’re going across.”

PRINCE: So you’re getting all this…

BRAWLEY: Well, some of this you get afterwards about what happened…about the causeway. We know we’re on the wrong causeway now…

PRINCE: You’re getting this by communication?

BRAWLEY: Yes, by radio. We know what’s happening and General Collins knows what’s happening and the things that he’s written and other people have written about the good communications that he had. He knew what was happening on the beach. He wanted to go in himself, you know, but that’s the kind of guy he was. But General Bradley, who’s back on the Augusta which is the headquarters, the army headquarters ship, he’s farther back, he wants him where he can keep in touch with him, you know. He doesn’t want him to go in too early. But General Roosevelt went in and he sent them across, and when they got across, the end of it had been secured by General Taylor of the – who’s from Missouri incidentally, General Taylor and…

PRINCE: Not Maxwell?

BRAWLEY: Yes.

PRINCE: Oh, Maxwell Taylor.

BRAWLEY: Maxwell Taylor, and he rose up in the army after that. He, with a few men happened to drop close to his…to that objective. He was to secure that second causeway which was a little town called Pouppeville and with just a few men, cause there wasn’t too much opposition there. But when they got across, they’d cleared the causeway and his decision, General Roosevelt’s decision was right and probably saved an awful lot of lives, you know, because there was, there was…they were through and they were through the causeway and they were onto land and without many casualties (several casualties, but nothing like they had at Omaha). Well then, this went on, succeeding waves came on and finally they cleared the…they and the 101st Airborne cleared the other causeways and later they began to put them over those causeways also later in the day…

PRINCE: And you watched all these people land?

BRAWLEY: Yes, as many…well you see, a lot of them were on my ship and then there were other ships that were carrying them too – landing crafts – they had…we had another thing which helped us on Utah Beach and that was a amphibious tank and it was a secret weapon and it had a…the tank had…it was a Sherman tank and it had a canvas top on it that could be filled with air, and it would float, you know. And they – each Corp had 32 of them 32 on Utah and 32 on Omaha. But the seas were rough that morning and the Officer in charge of that LST was bringing the tanks in, knew that or they had better not be dumped off in the sea with such rough seas…they might sink so he brought them in very close to the beach and 28 of them got in – well, they’re at the wrong place also. But they led the troops across. That helped a lot on Utah Beach all along there because here are the Germans seeing those tanks coming up and out of the sea. They don’t expect that and this helped. On Omaha…they dumped them about three miles off shore and they lost all of them except two or three. That’s another bad thing that happened on Omaha.

Now, we’re getting better communications by now and we’re getting a few reports back from the Airborne and of course we’re in constant communication with the Fourth Division and the Beachmaster whose job is to get them the hell off the beach! And so the headquarters from General Collins knew what’s happening and then General Barton goes in because he wants to be at the head of his troops and pretty soon they’ve got some security in back of the beaches. And then my job is done on the ship. All the plans were working and I was trying to get in on the beach to set up communications for General Collins when he got there, you know, because his advance CP is going to – Command Post. CP means Command Post, he’s got to be up there pretty soon.

PRINCE: How did you feel about going on that beach?

BRAWLEY: Well I didn’t really feel anything about it. I didn’t feel bad or good. I felt like, it’s just something that you do, you’ve been expected to go, you know. We really hadn’t much planning. I didn’t know how I was going to get in-land, once I got ashore. I knew that General Collins would have somebody meet him and take him in. And I knew the detailed planning of the Infantry would account for it. They would walk of course until they cleared the beaches, but I didn’t have any logistics worked out. It’s just…didn’t know for sure just when they’d go in, you know. It depended on what happened on the beach. You’re not going to go in like on Omaha…they didn’t get in with any of their people like Signal for a long time because they couldn’t get off the beaches themselves.

Anyway, it came time to when we got to set up communications in-land and this is around noon, or a little after noon as I recall. I don’t have any diary of it but I’m sure it was about that time and so a Major Executive Officer of the Signal Section and I – we climbed down (we call them scramble nets) over the side and into boats with some Fourth army people, you know, that were going in from the Bayfield. That was the name of our ship, and it’s quite a ride over choppy waters and your stomach feels a little queasy because of the water, not because…you aren’t really afraid – yes, you are too – you’re scared, but not in a urgent way, you know. You still don’t know what’s going to happen when you get in there. You can hear battle, and you can hear guns still. And on the way in, I can remember seeing a Spitfire – that’s a British fighter. It seems like he’s just up there watching and all of a sudden he just starts tumbling, you know. So the Germans have still got their anti-aircraft going and there’s an awful conglomeration or chaos on the beach. Not chaos exactly, organized chaos I guess would be the word. A lot of people are coming in and I couldn’t tell what’s happening much, but the Beachmaster knew and everything is going, and I can see it’s going toward Causeway Two. I can see one of our trucks, well several vehicles had been knocked out before they got there, but on the cab of one of them were some soldiers standing…three or four of them. There’d been trucks disabled…I don’t know whether they was hit or not, but there they are and the water’s only so deep and we’re going to be dumped off in a minute in that water. I wondered, “Why don’t they wade it?” You know. “Why are they standing out there?” Little things like this you can remember.

Then we got off in the water and we start wading in and we don’t know what’s going to happen when you get in there, and it began to take on…you asked me what it’s like…it began to take on an unreal…it seemed like a…it seemed like it was totally unreal. I thought it was kind of a play, you know, us being enacted, you can’t…dead people don’t look like they’re dead people. I think maybe it’s like on maneuvers. They’re going to get up and go on their way after a while and they tag them with a red flag…saying they’re dead! It just seemed unreal. But you’ve got to…you still are going…you know what you have to do. Fortunately for me and Westerner, this Major who was following me…he fell down in the water, poor guy – with his cigar in his mouth…and it’s wet. (LAUGHTER) he was not a very effective officer, to tell you the truth, or he’d been making the plans instead of me. Anyway, I look over here, and here comes a dukw out of the water…it’s a D U K W…that’s a amphibious two and one half ton truck. It will work…it floats in water and when it gets up to a beach like this which slopes up, it can come out. It was coming out of the water and the driver’s coming down like “this” and so I just hailed him and said, “Take us inland.” “Yes sir,” he said and I don’t know where he came from…I never did know. He probably came off of a LST or something, and maybe he didn’t know, and he was glad to have somebody to say what to do. Anyway, Westerner and I get aboard and we go down to Causeway Two. Now across that…it really began to get un-real because now there are dead Germans and there are dead G.I.’s that had just been pushed aside from the road, you know, to clear it. There was equipment pushed off in the water to clear it – there’s one of the D – D tanks that’s been…something happened to it. It had either been hit or for some reason or other, it was stalled and had been pushed off… everything was to get off the beach! And it didn’t look real, these people didn’t, the soldiers, you know. You feel a little detached from it really. I did…I may have been the only person in the whole army that ever felt this way…but I did, you know. I went ahead doing the things without any really conscious fear…

PRINCE: Mechanical?

BRAWLEY: Yeah, mechanical. But they didn’t seem real. But as soon as we got off the end of the causeway, and here are a few Frenchmen, you know. They’re waving a little bit…they don’t know what’s going on. They’d been bombed with the bombers and they know it’s the invasion because France and the Germans and everybody talked of the invasion. But now it’s back to reality, you know. It’s not the same because the beach is back down there…that’s the way it was in landing. That may not be typical, you know, but that’s the way I thought. But you see, I might have felt different if I had been a first wave, you know…when you see somebody and see them fall all around me, or something…it might have been different.

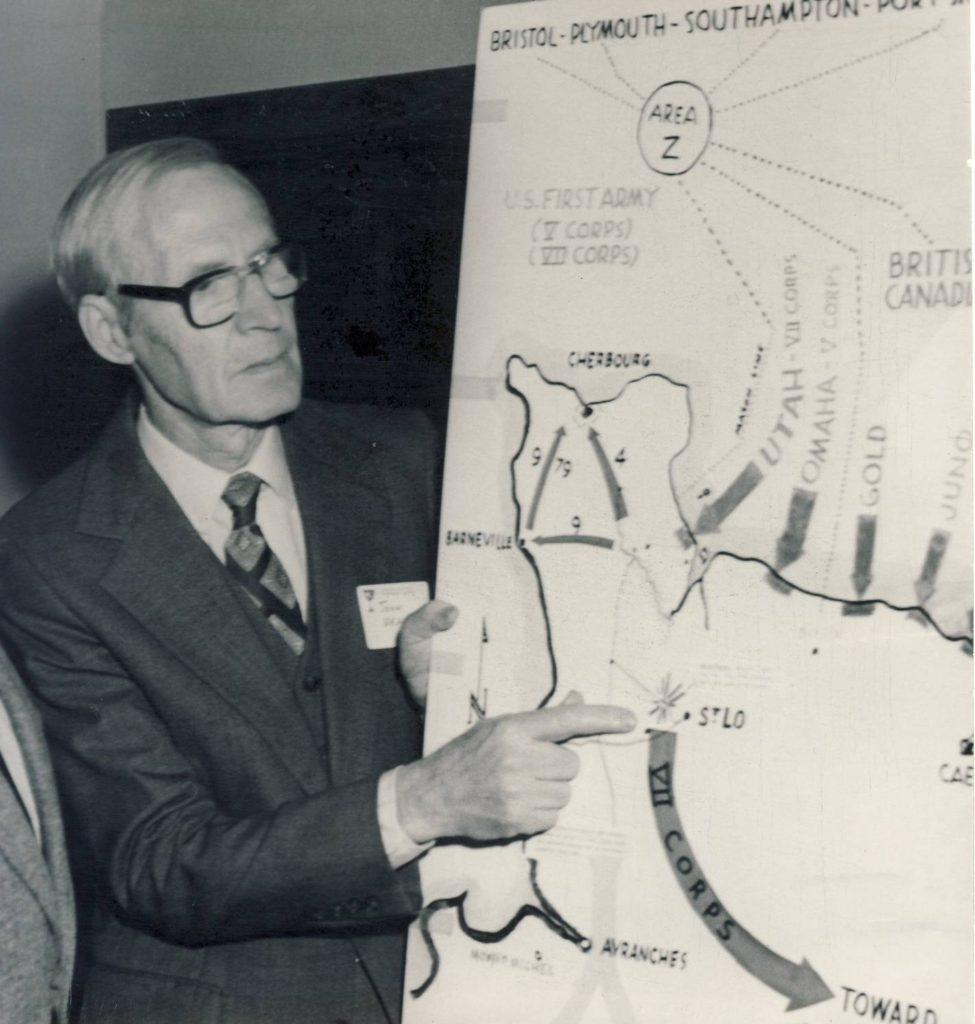

Now we’re on shore in France and the mission of Seventh Corp is ONE-A, “Seventh Corp assaults Utah Beach on D-Day at “H” hour and captures Cherbourg with minimum delay.” So that was Seventh Corp’s first mission in Overlord. Overlord was a code name given to the whole operation and so that’s what General Collins set about. And Cherbourg was a port and he was given about three weeks, I think, to take it and he got it in less time than that. But you see, they had to get an awful lot of supplies in and he needed a deep-water port and Cherbourg was a good port. It was down at the tip of the island…the tip of the peninsula. I can show you here where Cherbourg is. (SHOWS MAP) This is where the Seventh Corp went, you see, Cherbourg is down here…that’s the tip. And we landed right here…right along there and went up to Cherbourg and fought their way up to Cherbourg, but they also had to capture that in order to provide a port to bring their supplies on in. Well, before they…before it was captured, the Germans destroyed the port facilities, you know, and it took them about three weeks or longer to get it back into shape so they could use it.

In the meantime they had…down here on Utah Beach and Omaha too, they had what you may have heard it called… “Mulberrys.” They were portable breakwaters which were towed from England over here and sunk to make breakwaters…to make an artificial port and that’s where the first supplies came in…but you wouldn’t believe the supplies that we got…

PRINCE: What did you get?

BRAWLEY: Oh God…we got everything, you know. Just shipload and trainloads of guns, ammunition. An ammunition dump caught on fire and blew up, you know, a few days after D-Day, and well, “So what, we’ve got lots more.” The production of the United States was just enormous and it had all been piling up in England. And some soldier over there said, “If they bring any more stuff down here to Plymouth where we’re going to leave from…the damned island is going to tip over,” you know. If was just… the supplies…the action of the United States in providing war materials was just unbelievable!

PRINCE: So you felt very backed up?

BRAWLEY: Oh yeah, I don’t know how many…

PRINCE: Supported…

BRAWLEY: Oh, I don’t remember how many there are…who were back of each person who was fighting but something like…I know it’s over 10…it may be as many as 20 people in the army just supporting each person who’s up in the lines…and it’s enormous. Now all that’s got to come. It’s got to be landed and it’s got to come up here (SHOWS PICTURE) look where it’s got to go…300 miles before they got away from Cherbourg after it was made a port. It’s 300 miles up here to Aachen where one stopping point, where…that’s the Seigfried line up there. And they called it the Red Ball Express and it went…it just went…it had one route this way and one route back and just those trucks full of supplies…hauling mainly gasoline for the tanks. (SHOWS PICTURES)

PRINCE: All right…let’s…

BRAWLEY: That’s D-Day.

PRINCE: All right, that was D-Day. Uh…

BRAWLEY: The most memorable thing about D-Day was the battleships and their bombardment of the coast and all those airplanes that came over were just actually just right after the guns had started…so many of them. I really felt the war would be over that day. How can anything possibly live over there, you know. And I didn’t know they were dropping those bombs in too far inland and I didn’t know the determination of the Germans and the driving of Hitler to push them back into the sea.

PRINCE: When did you see your first German?

BRAWLEY: Well, on D-Day…that is a German prisoner. There were a lot of prisoners marching. I don’t know what happened to them to tell you the truth. We talk about Malmedy, but I don’t know what those people that took the Germans back towards the beaches would do with them when they got there. The Germans were afraid they were going to get shot. I know that some of ours…there were some horrendous things that went on on D-Day among the paratroopers – people who were fighting almost hand-to-hand and nothing to do with the prisoners when they took them. And it’s easier to kill them. This only lasted for a few days. But the Germans were, they believed in the military. They believed in the dignity of the military. They were really not – I don’t have any reason to believe that they were doing anything like the atrocities against the people in concentration camps or the political prisoners. They had respect for the military, you know, for the army. And I think they treated them as well as they could. I talked with a young – not a young fellow, bout my age, I guess, who was captured at the Battle of the Bulge and about a week ago we had a reunion and I asked him about the treatment of the prisoners. Well…

PRINCE: A week ago now?

BRAWLEY: Yes and because he was captured up here at the Bulge and he was in a prison camp for about three months until the end of the war. But his experience was not…he wasn’t too happy about it because he said they shifted him around different places and they starved him and all. They didn’t give him food. But he sorta admitted, and I think it’s true, that that’s the best they could do, you know. They were trying to save themselves.

PRINCE: Well, what you are saying is the German soldier was not your Nazi SS.

BRAWLEY: No, no, that’s right. And I want to make a point that the atrocities were against the political prisoners they called them, and they were barbarians from the top on down to the very lowest. They accepted it, you know. You had to have people to run the camp. In Nordhausen they all took off…most of them took off when the army was getting near but they had to see it – they had to see those people daily in the camp so they accepted it…but not for prisoners.

PRINCE: Well let’s not…let’s not get too far ahead.

BRAWLEY: All right, okay.

PRINCE: Because we’ll examine that when we get to it. All right…just trace…trace your route and then…to where you get to Nordhausen, and just briefly trace that route.

BRAWLEY: All right. We, after taking Cherbourg which as I said took about 20 days, from the time of the landing and then the Seventh Corp came back down to…from Saint Malo. Every crossword puzzle worker knows about Saint Malo. You know, a French town. That was a spot where a breakout was made…from the hedgerow country. This was hedgerow country down there, and it was sort of a farming land…orchards. They raised apples and made calbadose drink which is like carbolic acid. And after this capture they were fighting through the hedgerows and now all of the troops are coming in every day and their supplies are coming in and they were getting congested in the area and they have got to break out. And I’m going to say something which is controversial, but over on the British sector at Caen where General…Field Marshall…he wasn’t a Field Marshall then – but he was a General…Montgomery was supposed to take off toward Paris across the Falaise Plain…and when they got through with this, and they got done and about finished with the hedgerow country, he’s still sitting over at Caen and he hasn’t gotten through at all. So this controversy about whether he was supposed to go on or not, although it’s pretty clear that he was supposed to go on.

PRINCE: Caen is C A E N?

BRAWLEY: Yes, about right in here. (SHOWS MAP) Right in here I guess it is. Yes…right there is where the town of Caen is. And he was supposed to go across this plain to Paris and then when they finish this, the Americans were supposed to come down here and protect the flank…he’s still sitting there. So the job then is given to General Bradley who was the First Army Commander at that time. He later was Army Group, but he was the First Army Commander and the Seventh Corp was part of the First Army, os he’s got the job now. Eisenhower and his planners gave him the job of breaking out because you’ve got to get back and started out of that beach head or you really are going to get pushed back in the ocean, you know. So they had another D-Day really…another big bombing of the line at Saint Malo.

So General Collins was chosen to make the break-through again. Everytime there was a tough job…Collins got it and rightly so, I think, because he was a good General. Anyway, another big carpet bombing and I sat in back of this line…in back where our command post was and it must have been a mile away and clothes were flapping…the breeze…from the concussion of the bombs, you know, so many of them. And they were…they were troops, our troops, were drawn up against on a line on one side of the road which they were using as a guide and the Germans were dug-in on the other side. And so they dropped the bombs and here again, they screwed up! The first ones were on target, the target maker marked them perfectly and the first wave dropped their bombs right and there was a very little breeze blowing back towards the American lines and so succeeding waves dropped them and hit the 30th Infantry Division and some of the Ninth Infantry Division and killed General McNair who was there as an observer from Washington. And before they could correct it, you know, and it was another bad scene as far as the air force was concerned…but not too bad.

PRINCE: Many mistakes must have happened like that.

BRAWLEY: Well, those were the worst, I think, those two…as far as the air force was concerned.

PRINCE: Where were you?

BRAWLEY: Uh…where was I? I was back about a mile back on the American side at the Corp Headquarters. But we were all out there watching the planes come over and you could see them. When they first came over they’d get hit and they’d spiral down, you know, with black smoke and you’d see parachutes and sometimes you wouldn’t see parachutes. And then they’d stop because the fires had knocked out all the German ack-ack.

PRINCE: So, your job was really to coordinate what was going on in different places?

BRAWLEY: As far as communications was concerned. I went on every trip from here to Leipzig. Every time the Corp started moving up, my job was to go with the advance element and select a new Command Post, you know, with General Collins representing Signal.

PRINCE: Signal Corp?

BRAWLEY: Yes, and you’d go and you’d pick a suitable place that would be suitable from a communications standpoint. You know, you can’t get way off somewhere where you can’t wire and radio to them and there’d be a few people from each section would go on “advance party”…they called it. We went…then broke through here and General Collins made a decision to send his tanks through and that started the march across France, that you’re heard about. It never did really stop until it got to the Siegfried Line. He cleared the way. This was in July of ’44. He cleared the way for General Patton. You must have heard of General Patton…

PRINCE: Absolutely.

BRAWLEY: …to go down into Brittany. Now if you ask…this is a little personal bias that I’ll drop, but if you ask anybody who liberated Paris…who had the only tanks…who made the drive across Germany in tanks…they’d say, “Oh, General Patton, who else? Old blood and guts!” General Patton wasn’t even in the war at that time. General Patton…

PRINCE: Wasn’t he in Italy around that time?

BRAWLEY: Pardon? He was still over in England. Well, he may have been over there but his Third Army didn’t come until August first. And then when they did, they went down here through an opening that had been cleared by the First Army. Anyway, the Seventh Corp comes around down to the Falaise pocket near Argentan. They were to come down and encircle two armies of the Germans who were down there near the beach, you know. They were…Hitler’s still telling them to push them off the beach. Montgomery has got 22 miles to go from his side…the First Army has got 110. They get down here and Montgomery isn’t there…so most…a lot of Germans got away through the gap but an awful lot of them were killed and an awful lot of them were taken prisoners. The Seventh Corp took 8,000 prisoners there. I went out into that battlefield after about the next day after it was over, and it was unbelievable…much worse than D-Day as far as killed people that you could see…equipment, animals, dead Germans. The G.I.’s had been…the Americans had been picked up already. It was awful…it was…even bad. Eisenhower wrote that it was the biggest killing ground of the war that you could…He said, “I was escorted through the area 48 hours after the battle and you could literally walk for hundreds of yards without stepping on anything but dead and decaying human flesh.” But that’s…I was through the same place and I think that’s exaggerating a little, but there was an awful lot of people, you know. It’s unbelievable what war is. War is really hell, you know, and something like that…people killing each other.

PRINCE: Did you…did you ever get, I don’t want to use the word “accustomed,” but did it get easier to see it, or…?

BRAWLEY: Yeah, it got easier. It got easier but it started easy. But I told you on the beach they were players and each time, I think, when I ran into something like that it was too bad but it was not like you’d see somebody now…if I saw somebody out on the street that had been killed, I’d think about it, you know. That’s a shame but it’s just a consequence of war…unless it happens to somebody you know.

PRINCE: Yes. Oh then, you were not shooting, killing, you were…

BRAWLEY: I was seeing what somebody else had done.

PRINCE: You were seeing it, but you had a job to do.

BRAWLEY: Yeah. I wasn’t pulling the trigger. Now a friend of mine, a good friend of mine…

PRINCE: Do you think about that John. Did it occur to you what you were doing…that you were lucky or…?

BRAWLEY: Yeah I think so. I think it did. I think I believed that…I didn’t seem as close to it. I don’t ever remember thinking, “What would I do if I had to fire my carbine which I’m carrying at somebody and kill them.” Would I feel any different? I thought I would if the occasion demanded it. It was not my job to shoot them, you know. My job was to furnish communications, and although everybody was supposed to fight when necessary, I just never did. I didn’t get too close to it. But when a friend of mine got shot and I thought he was going to die and thought he was going to be evacuated, and never see him again…then I felt bad. You know this is like somebody that you know real well…it’s different. I think surely the soldiers must feel that impersonal feeling about it, otherwise, they couldn’t…they couldn’t accept it, you know.

Every now and then you get touched with something that you’re not prepared for. I saw some bad scenes in St. Mere Eglise, that’s just in back of the beach on the next day after D-Day, I guess…where a little building had been used for first-aid station and there was plasma bottles all around. There was blood all over the floor and pieces of clothing and so on. And I see a shoe, a paratrooper boot lying there and wondered why the guy went off and left his boot, you know… a silly thing to do. And so I picked it up, still laced. I picked it up, and it still had a foot in it and that kinda of…I put it down real quick – and that’s something I wish I hadn’t seen.

Then I guess, the next day I came upon a scene where there had been a fight and in the hedgerow country…there are two hedgerows…and in between there’s a little depression, kinda like a path or a road maybe, and I walked up and here are four or five dead Germans…no American troops.