Allen Sabol, a resident of University City, MO, was a prisoner of war while serving in the U.S. Air Corps in Europe. His plane was shot down over Germany. He was interrogated at Dulogluft and was a prisoner from April 1944 to February 1945 at Luft 4 Camp. He describes the camp routine. He was on a forced death march of 10,000 prisoners in January 1945. He describes his liberation by the British and rehabilitation in the United States.

Allen Sabol

Mapping Allen's Life

Click on the location markers to learn more about Allen. Use the timeline below the map or the left and right keys on your keyboard to explore chronologically. In some cases the dates below were estimated based on the oral histories.

Read Allen's Oral History Transcripts

Read the transcripts by clicking the red plus signs below.

Tape 1 - Side 1

PRINCE: This is “Sister” Prince, and today is July 20, 1988, and I’m interviewing Allen Sabol for the St. Louis Center for Holocaust Studies, Oral History Project.

Allen tell me when were you in the army during the Second World War? 1940 what?

SABOL: ’43, early ’43 if I’m not mistaken when I first went in.

PRINCE: And you were approximately how old?

SABOL: About 21.

PRINCE: Where did they send you?

SABOL: First we went to Jefferson Barracks and then from there we were sent to Sheppard Field, Texas to take our basic training.

PRINCE: And you were in the – ?

SABOL: Army Air Force.

PRINCE: Army Air Corps.

SABOL: Air Corps, yes, I guess you’re right.

PRINCE: (LAUGHTER) What was it like to be away from home?

SABOL: It was a unique experience because quite frankly, I was an old-fashioned type person and home was what I liked being with. And, after all, you live in a neighborhood and you grow up with the same people you go to school with and it was different. Because of my religious convictions, eating was extremely difficult. I tried to keep kosher and, to the best I could, and it wasn’t naturally a necessity since we were allowed to do what we had to do. We had to go fight to defend our country and so keeping kosher was not an adherence that we had to look to, but – however I felt it was extremely important.

PRINCE: Did you have an opportunity to do that? Did they allow you to?

SABOL: Well, there was no way to keep kosher because, naturally you had to eat from the same food, but I didn’t eat the meat and I tried to stay away from things that were cooked with meat, tried to do the best I could under the circumstances. Not having a formal background in Judaism, but coming from at one time an ultra-religious home, my parents were. They got away from it a little bit and would come back, you know. But I thought it was important to have something to hang on to. Judaism represents an extremely important part of my life.

PRINCE: That’s interesting. It wasn’t a – it was an observant house as far as rituals were concerned, but you’re trying to say that you were not –

SABOL: I wasn’t completely observant because I worked on Saturday. Not having gone to become Bar Mitzvahed, you, you know, not having gone to a formal school of learning, I wouldn’t know where to begin.

PRINCE: How were you treated in the Air Corps?

SABOL: Well there was some anti-Semitism because almost – from the very beginning you have that feeling and you know it’s there and you just try to make friends with people of your same faith or those who were not out to give you a hard time. And there were a number of people from other faiths. It seems kind of strange. We did go into service with a number of St. Louis boys and followed through. Some of them were Jewish and some of them were Italian and it seemed like we got along better with those people of the Italian race and our particular situation. I mean, you could work around it. It wasn’t always – it wasn’t the thing that should have been happening. But you could –

PRINCE: How did you work around it?

SABOL: Well I guess you overlook things. I don’t know – I wouldn’t do the same thing today. I wouldn’t overlook. I don’t go out to appease people because of my religious convictions. I don’t work around my religion. I’ve come to the point where I feel I’m not running anymore (LAUGHTER) and I’m going to stand up for my convictions and my religion. And let the chips fall where they may.

PRINCE: So you may, let a remark drop –

SABOL: Yes, you would overlook –

PRINCE: Like you didn’t hear it.

SABOL: Yes, you’d overlook it, you know. And of course I couldn’t understand it because we were all there for the same purpose. But it was there without question.

PRINCE: So how did you take the army life besides that?

SABOL: Well you know, under the circumstances you have to adapt because I think everyone in the service at the time felt that there was a job we had to do. Army life was difficult, especially if you weren’t used to the basic training aspect. (LAUGHTER) It was pretty tough, pretty tough. It was a difficult time. I mean, it was something you worked at and stayed with it, tried to do what they’d tell you to do, and it worked out, it worked out.

PRINCE: Were you frightened?

SABOL: Well, not really, not really, because flying was something I really, really wanted to do. I was very interested in it. I really wanted to – I wanted to be a pilot. And it’s something I just had a liking to do.

PRINCE: So you became not a pilot?

SABOL: No, I – after basic training, I did finally after several tries pass a test to start pilot training and I was given the permission to start. I got orders to go start the pilot training, but before shipping orders came through, I also got orders to start gunnery training because gunners were – well, the loss of airplanes were considerable at the time, a very difficult time for the Air Force, the Air Corps, and gunners were in short supply, so I couldn’t get to start pilot training, went to Harlanton, Texas to start gunnery training. From there we were sent to Pueblo, Colorado for advanced training. I had a particular problem that I used to get airsick.

PRINCE: Oh.

SABOL: So the place to be was not in there because some days you would practice takeoffs and landings and it was a tough time, but I still knew I had to do a job. There was something I had to do and I was very determined. I was released from the crew that I was on at that time, because of the airsickness. I asked to be placed on another crew. There was an opening and, of course, that pilot didn’t know why I – what the problem was behind me, didn’t ask. Everybody was busy. It was a busy time, busy time. You were going all the time constantly. I did lose some time in training but that wasn’t too important. I started out as a nose gunner and wound up as tail gunner.

PRINCE: What’s the difference? I know one’s in the nose and one’s in the tail, but what is the difference?

SABOL: Well the positions, just because they’re different, it doesn’t make a whole lot of difference in flying however. But there’s the mechanism that you work with, the turret and the gun. The guns are normally pretty much the same. The turret operates differently from one to the other.

PRINCE: What is a turret?

SABOL: Well, that’s a thing that you sit in and you learn how to maneuver it back and to side to side, up and down. You learn the particular sight that is in that particular turret because each position requires a different kind of a gunsight, and this is what you learn in training, how to use these different sights.

PRINCE: Can you see more in the nose or in the tail?

SABOL: Not really. In the tail you see where you’ve been. In the nose you see where you’re going. The pilot relied on the tail because his line of sight was not that good back there. So he relied on tail gunner reporting whatever I saw out there coming at us from that particular position.

PRINCE: So it was only one in the back but there were a couple in the front?

SABOL: Well in our particular plane, which was the B-24, it was a Liberator.

PRINCE: Oh.

SABOL: There’s a difference, you know. There was a tail gunner. There are two waist gunners, one on either side of the plane. You have what’s called a Sperry ball gunner (bottom gunner) and you have a top gunner, and you have a nose gunner (LAUGHTER) – all kinds, all kinds. There are 10 people in the crew.

PRINCE: 10?

SABOL: Uh-huh, 10.

PRINCE: Well, so you’ve named the pilot, the –

SABOL: Co-pilot –

PRINCE: The co-pilot, the nose gunner, the tail gunner –

SABOL: You’ve got the navigator.

PRINCE: The navigator –

SABOL: You have the bombardier.

PRINCE: The bombardier and –

SABOL: The top turret, the bottom turret, two waists –

PRINCE: Two waists.

SABOL: And the tail. It should be 10. It should add up to 10.

PRINCE: Whatever.

SABOL: Unless you’re flying a lead ship. They normally add another person to help locate the target, make sure you’re in the proper area and everything.

PRINCE: That’s a lot of people, a lot of people to get along together.

SABOL: Well you work as a crew. Sad as it was, our particular officers were not that sociable as some other groups were, but it had to be a team effort because one relied on the other in many, many aspects.

PRINCE: What was the name of your plane?

SABOL: Lieutenant –

PRINCE: No, the plane.

SABOL: Oh, the plane. Well, we did not have our own plane. You take training in various planes here. After you finish your overseas training, you’re sent to what’s called a “staging area” which was in our case Topeka, Kansas, and they told us there that we would pick up a new plane and we would fly over to our destination in England. When we got there, there were only five planes for 55 crews, so they put the names in a hat and drew out five. We were then sent to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey and we boarded the Queen Elizabeth, the biggest thing afloat. (LAUGHTER) It took us all day to load and the only happy thing about that is that Glenn Miller’s orchestra was on. He was not – he flew across. The orchestra was very obliging, played many jam sessions, the ’40 tunes. I mean, this was the real genuine Glenn Miller orchestra and it was thrilling. It was thrilling! So you overlooked the food and the seasickness and everything else and it was just swamped. How it stayed afloat we don’t know because of the amount of men it took on. It was unreal, unreal.

PRINCE: So you got to England.

SABOL: We landed some place up north. I think it was Scotland, took the train down, stopping at several areas and got to another area where they sent us over to Ireland for two weeks advanced training and from there we were assigned to our base in England. We flew across to England, landed at our base. We still did not have our own plane. Because of the losses here in the States and overseas, they could not keep up with the number of planes that were needed.

PRINCE: Are we still in 1943?

SABOL: No, we just went to 1944.

PRINCE: Okay.

SABOL: We lost some time in between there.

PRINCE: That’s all right. I’m just trying to keep up with –

SABOL: And a lot of strange things happened. One fellow who I took basic training with, I ran across him in England, same base. It was just – you know, so many things happening.

PRINCE: So when did you take your first flight?

SABOL: Uh – I can’t tell you the exact date but it probably could have been June, July, sometime late June.

PRINCE: And where did you go?

SABOL: I wouldn’t remember the first bombing raid, if that’s what you’re referring to. It would be difficult for me to remember anything but the last raid.

PRINCE: Then let’s talk about the last raid. Where was the last raid?

SABOL: We were assigned to bomb the submarine pens at Kiel, Germany. It was a very, very important mission. It’s what was called a “Maximum Effort.” Everybody goes but the cook. (LAUGHTER) As many planes as were available at the time, coming from all out of England, were to be bombing this area and surrounding areas. It was going to be a big raid, a very important raid, Kiel, Germany. They had to stop the submarines and this was their main base. The problem with that was the fact that out in the bay area of Kiel, whatever old ships that were not able to do any – see any other further service, were anchored out in the bay and the decks were lined with their 88 milimeter gun which was an extremely accurate gun and the gun that everybody feared. The German 88 was something that we couldn’t – it was hard for our country and England too, no matter who – to reproduce something that was as efficient a gun as the 88. Extremely efficient.

PRINCE: It could get the bombers as they came in –

SABOL: Oh! No matter what heighth you were at the time, this gun could shoot well above. There was no plane that could fly higher than this gun, this 88, could reach. It could reach any plane at the time. You know, you’ve got to remember, there were no jets. We had a number of different fighters. As a matter of fact, we would pick up three different kinds of escorts coming out of England. Like we would pick up – I think it was P-47’s and after we got into or over France or a little bit further into Europe, we would pick up P-38’s.

PRINCE: You had escorts.

SABOL: Yes.

PRINCE: They were the ones that –

SABOL: Well they would fly off to the side. See, the bombers in those days were very slow. The fighters were faster, naturally. Fighters are always faster. They either would fly off to a distance and watch for other enemy fighters and then they would engage them to try to protect us the best they could. After we got into Germany and closer to the deeper inner penetration, we picked up P-51’s which were always a glorious sight to see because we felt very comfortable with them. Those were the best we had, the P-51. It could go the furthest. It could protect us in the best way.

PRINCE: So tell me what happened.

SABOL: Well, we – I can’t tell you exactly at what point we started getting hit. I cannot tell you that. I don’t know.

PRINCE: Did you have a chance to drop your bombs?

SABOL: Yes. Now whether it was before or after, I don’t remember. The things I remember is that the skies were full of our planes. We started to see red flak. That was a designation of one of two things. They’re tracking you with the red flak because they can see – it’s a tracer. They can see where it’s going. Their ability to hone in on an airplane gets to be a little bit finer with the red flak. The other thing is, that they used to tell us in training, when you see the red flak, it could either be that they’re tracking you or they’re going to stop firing and their fighters are going to come in to attack, because it’s difficult for them to shoot at you while their airplanes are, their fighters are coming in to engage you. So, naturally, it didn’t make much difference what was going to happen, because when we got our first hit, I suspect the first or the second hit, the pilot – and I’m telling you these things from what I learned later – he lost control of the plane because the ailerons, which are needed to turn the plane off to one side and start making your return trip, were shot up. We lost an engine. We had to continue straight, one way. We started getting hit some more. One person hollered over the intercom, “I’m hit!” Well, instead of telling us what position or – we didn’t – I didn’t know. I’m in the tail and I don’t know what’s going on. All I can see is the smoke coming from the engine that was hit. And I don’t know too much what other consequence is taking place and when this person hollered out, “I’m hit!”, the bombardier and navigator, who are also in the nose section of the plane, thought it was the nose gunner that hollered, “I’m hit!”, and they pulled him out of the turret. And very, very fortunately, because almost a direct hit took pretty much of that. It was a miracle, a miracle.

PRINCE: It hit where he had been.

SABOL: Yes ma’am, and they would not have been able to find him because that’s how bad that turret was – it disappeared and it was just bad. It was just terrible. And, of course, the force of that threw them all back. I called on the intercom to ask the pilot if he minded if I leave my station, because I – you know, something’s wrong – you just have the feeling that things aren’t right, something’s gonna happen.

PRINCE: What did he say?

SABOL: He said, “Okay.” He said, “All right.” And when I got into the waist section of the plane, I saw that the right waist gunner was the man who was hit. Quite a bit of his leg, the thigh area, was blown away. The best I could do was put some sulpha – we had little first aid kits and they tell you, you know, they tell you all these things. But in the heat of battle, I don’t think too many people know what their reaction is gonna be. And quite frankly, unless you’re there, I don’t think I’d rely on someone telling me what they’re gonna do ‘cause I don’t know that I could do what I did, quite frankly. There are a number of reasons, because when you see this mess, it’s just – it’s very frightening. Besides I had to keep under oxygen and I was having a problem finding an outlet. You know, after you go to 10,000 feet, you automatically start oxygen because the air is thinner and you have to have it. As a matter of fact, every so often there’s an oxygen check. Someone in the crew or the pilot or co-pilot will check every position to make sure everybody is okay, that the lines aren’t blocked. They have a way of freezing up because of the moisture that you’re breathing drops down and it can freeze up. Since you only have one mask, you have to take care of it and there are ways of overcoming these things. And they did want to keep up with what was going on, try to get a radio hookup. It was – I don’t know what I did, honestly. All I did – the only thing I can remember is that I did open up some envelopes of sulpha powder and put it on where he was hit. And they have what they call a “serette” of morphine. I must have given him a couple of those. I must have given him a couple of those. I mean, I know I did. They tell you how to do it. I couldn’t do it today. There’s no way I would know how to do it or what to do. How I did and what I did is –

PRINCE: What is a “serette”? Is it a syringe?

SABOL: No. It’s a little glass thing, a vial or something. It’s kind of thin. I mean-

PRINCE: You crack it open or something?

SABOL: I guess so. I don’t even know how you could administer it.

PRINCE: But you did it?

SABOL: I had to. I had to. And try to put some bandage on him, you know, and he was, you know. Sad to say, the other waist gunner, Lefty, didn’t do anything and, of course, he shouldn’t have done this, shouldn’t have left him. I wasn’t a hero. I just happened to be – to come across him. And I knew that we were being hit and the pilot – you could tell that things were happening because the gasoline was pouring into certain areas of the airplane, which is extremely dangerous. Why our airplane didn’t blow up is – we just – so many things happened to us –

PRINCE: Were you aware that you were losing altitude?

SABOL: Well I don’t know if we were losing altitude too much. Since we were coming over the target as being one of the last elements, as they speak of, we would be flying a little bit higher than most because by the time we got there, they knew your direction. They knew your speed. They knew all the things that they had to know to be more efficient in firing their guns. So they try to put you a little higher. And I don’t think we lost too much altitude and I couldn’t even tell you how long all these things took because I had no – time was something we didn’t – wasn’t interested in anyway. And then a couple of us were in the waist part of the airplane and we were told that we were going to leave the plane. Those people in that area have a different way of leaving the plane than those people in the front of the plane. We had what’s called “bottom hatch” and you just open up this door. And you get down on your knees and you tumble out. That’s how you do it. Now you don’t get much – you don’t get any practice on this and you don’t get any practice on using your chute because they can’t simulate, or they weren’t about to simulate – they didn’t have time to do these things, and you just had to react with what was around you. And (SIGH) when we first looked out, we saw water and I wouldn’t be here today if we did it. We jumped. There’s a special way of jumping into water, as opposed to jumping on land. Not too many people – you won’t talk to too many people who’ve jumped in the water and are here today because the way – what you have to do – remember, you’ve got to get rid of your parachute as you hit the water. There’s a special way of doing that, ‘cause you don’t want to be under that parachute. The other thing is, you wear what’s called a “Mae West” which is another word for a life jacket and you’re supposed to pull the thing and it’ll inflate. Well, whether it will or will not inflate is something else. I mean, you never test these things out, you never test them. You never test your parachute until you – you always go on a mission thinking, “Nothing’s gonna happen to you. It’s gonna be the other person, the other man.” Actually, you don’t think of you being hit or anything happening to you. So, jumping over water was rather – I feared it. I was very – I don’t know if I could have done that. Looking back today, I don’t think I could. I honestly don’t think I coulda made it. In a few moments, once we start seeing land, the gunner that was hurt the worst in our crew, we put him on what was called a “static line” and so he would not have to pull the chute himself. We did not know – we didn’t – how it came to us to do this, I couldn’t tell you, because he did pass out as we put him out of the plane, you know, got him out. And the static line pulled the ripcord. He landed okay. I was the next one out and instead of doing the thing that you’re supposed to do, I did one thing that was wrong, and that was to hang on to the side of the plane as I was leaving, and in so doing, I – well, almost pulled my arm out because of the plane’s speed and the engine’s coming back. You’ve stood behind airplanes and had the wind coming up against you. It’s pretty forceful, and I got caught in that. And that’s why you always count to 10 to get away from the plane, to get away from that because no one opens up their chute immediately. You get caught in what’s called the “slipstream.”

PRINCE: Slipstream?

SABOL: Slipstream, uh-huh. That’s why you count, to clear the airplane, to clear the slipstream.

PRINCE: All right.

SABOL: If you do open your chute too soon, there’s very – you have a chance of – well, I guess your parachute could be pulled completely off of you, or you could sustain some injuries because of the suddenness. It’s just something you just don’t do.

PRINCE: So what happened to you?

SABOL: Well I lost the use of my right arm.

Tape 1 - Side 2

I opened up the flap on the outside of the parachute to get the pilot chute which is a very small thing, and once the wind hits that it trails out the main chute and you’re okay. And I always had the habit of taking along a – I don’t know if you’d consider it a Siddur or a little prayer book that was issued to the Jewish fellows in the service. Gentiles got their prayer book. We got ours. Half of it, one side, is in Hebrew which I could not read. I did not know. I did not know Hebrew. The other side was English and I always had the habit of – especially when we were starting to go over the target, we came to a certain point and from there on it was a straight flight which made you very vulnerable. I used to start reading this, and coming down in the chute I read some more of it, you know, because –

PRINCE: In the sky?

SABOL: Well, that was it, yes. It’s a small book. I had the presence of mind to take it with me and got down on the ground.

PRINCE: You landed safely.

SABOL: Well it wasn’t too much of a safe landing ‘cause, like I say, I lost the use of my hand. The wind was blowing and it was difficult getting out of this – folding up your parachute so you could get the wind out of it.

PRINCE: And you put the prayer book back in your –

SABOL: I must have put it back in a pocket, yes. To tell you the reason why, I’ll come to that. I was turning from side to side and finally the wind died down a little bit and I could collapse my chute and get out of the harness.

PRINCE: Excuse me. Was this at night?

SABOL: This was during the day, the afternoon.

PRINCE: The afternoon?

SABOL: The afternoon, yes. I don’t know what time. (SIGH) I can’t tell you the time. I’d say it was early afternoon. We used to leave at daybreak to – we’d get up at around ten in the night, wash, eat, go out, ready the plane, go to briefing, and by the time, weather permitting, we would leave around daylight because it took some time to get – especially if you’re going far into Germany, you needed all the daylight you could get. And I would suspect that it was sometime early afternoon when we got down on the ground, and it wasn’t but a few moments that I was surrounded by farmers or whatever. I don’t know.

PRINCE: Farmers?

SABOL: Farmers. Because it was pretty flat area and I think it was a farm area that we landed in.

PRINCE: How did you feel?

SABOL: Very exhausted, very exhausted. That would be difficult to explain. I knew I was in Germany and I knew of some of the problems that were facing our people.

PRINCE: For the sake of the tape, you mean Jewish people.

SABOL: Yes, yes.

PRINCE: I’m just letting people who will listen to this know.

SABOL: Uh-huh. Because some stories came back to us, especially those that were Jewish, some we were told got rid of their dog tags so they wouldn’t know their religion. Some of them that were found out that they were Jewish, we understand that they received some treatment that we could anticipate which was not very good. Being in the Air Force, or Air Corps, we knew that if the civilians got to us, they could dispose of us very quickly and they did this in many cases because we were the ones that they were confronted with, with the destruction that was going on, you know. Sometimes bombs landed in schools and hospitals and homes and different things, and which, in Germany, we – you know, the thinking was, if you had to dispose of your bombs, dispose of them anywhere in Germany. In France, try to keep them until you got over the channel or try to keep them. Good. So, naturally, the German population, the civilian population was very much – what word can I tell you?

PRINCE: Against you.

SABOL: Oh, they were – they were pretty much whipped up in a frenzy which we were told. You know we were told some of the things we could anticipate. So it wasn’t but a short while, and of course, I sure was looking for something to drink. I was very thirsty, very tired, very hungry. It was just a very exhausting time and it just really was difficult to deal with.

PRINCE: Did they have guns?

SABOL: Yes. Then the local police came in, took us to –

PRINCE: Us?

SABOL: Yes. There was one or two of our crew that were together, that landed fairly close, and I’m not sure exactly who they were. I think it could have been the pilot or one of the other crew members. I’m not sure.

PRINCE: So you were with two other people?

SABOL: Two or three. I’m not 100% certain of that.

PRINCE: It’s not important.

SABOL: And they took us to a place, and here I just don’t know what preceded one thing or another. The things I do remember is that there was this – I’m trying to assume it was a German soldier who was interrogating me, taking whatever I had such as the escape kit and whatever things that they wanted, you know. And then, actually he wants your wings and then he sees this prayer book and he could look at my dog tags. They had the experience, they knew, they had enough previous people coming and being shot down to know what to look for, you know. And since he could see that I was of the Jewish faith and I had this book, he became rather –

PRINCE: Abusive?

SABOL: No he –

PRINCE: Agitated?

SABOL: Yes and boisterous or whatever I can say. I know he – the things that I can remember him saying was “Geflugter Judin,” which is – I think it means “Damn Jew,” whatever. And then I knew that he was very much – he was jumpin’ up and down. Oh, he was very – it was pretty difficult. And when he turned to do something – I was trying to get that prayer book but I wound up getting my wings back because he didn’t see that. I would have liked to have had the prayer book. Whether that would have been beneficial, a good thing to have at the time, remains to be seen. I don’t know. And then about the only other – two other things – one of them was that there was eventually three or four of us from the crew that were brought together. And then it seems like the local population, the people around there, they could tell. They knew we were Air Force. That was no problem with them. And they were getting worked up by one particular person, a typical German without question, and it seems like what I could recall is that they were talking about perhaps they would hang us. The local police, I think, saved us at the time, took us to another area, got us out in a truck because this one German was working them up into what we – you know. You could understand some of the things that were going on, not too much. But you had an idea what was happening. And then they took us to another place and I was in solitary for a day or two. I don’t even know, you know. You lose track of time. I don’t know if we were given anything to eat, what we did or what. The next thing, I did see our pilot and a couple of the other crew members, and the pilot had the option of asking the enlisted men if they wanted to go to the officers’ camp. With the army, when they were taken prisoners, officers and enlisted men generally would go – would be sent to one camp, the same camp. The Air Corps, they separated the officers from the enlisted men. And there was a reason for that, but I don’t know what that was at this time. I don’t know. The officers had the option of asking us to come with them. With several of the enlisted men, we decided that we did not want to for the fact that the officers were not – they weren’t friendly or sociable. We just did not associate when we were in the air. And when we got down on the ground, we did what we had to do and we separated. Some of the other crews were very – it was a close knit group. But ours was not.

PRINCE: That’s really too bad, isn’t it.

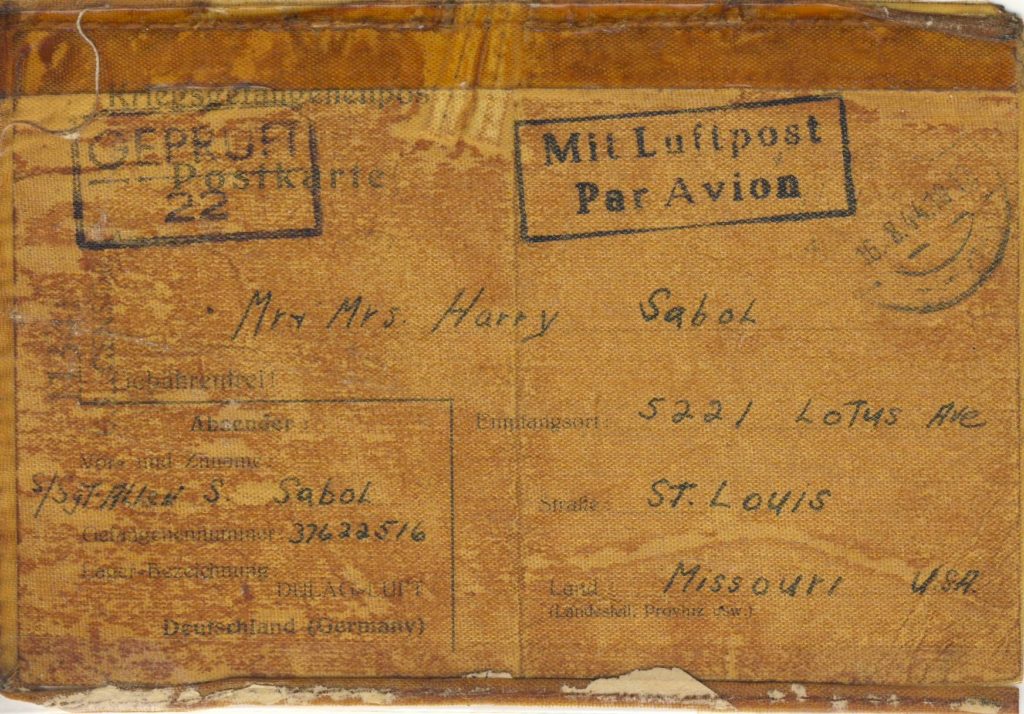

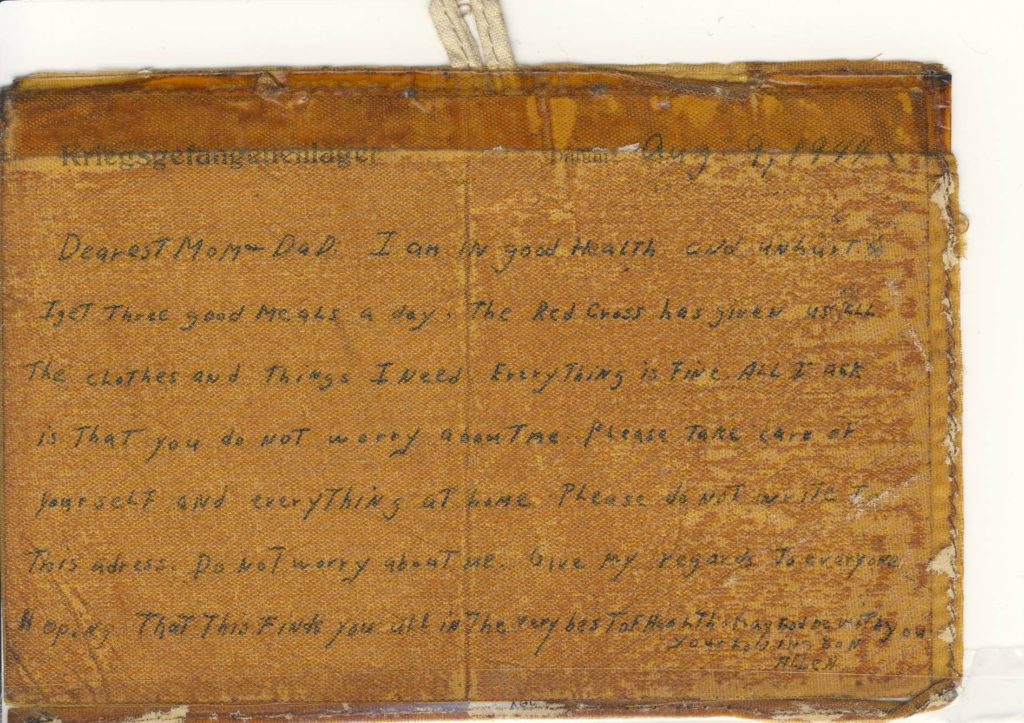

SABOL: Well, yes. But then when I look back at it, I feel that the pilot, coming from – I think his father was an army man and I guess some of this rubbed off on to him and he felt that you saluted. I mean, you had your tie on, your buttons buttoned, everything was strictly what we called “GI.” Everything was done according to the book. Other crews didn’t. You know, it was a flexible situation that the Air Force enjoyed. So we – several officers were there, one or two or three enlisted men, and we decided that we did not want to go. But the pilot did see my hand and he seen that I had problems and was bandaged and everything, and he said – it was the only thing I can remember him asking us to go with him. The other thing, he said, “If we ever get back to the States,” he says, “I’m going to put you in for a purple heart.” (LAUGHTER) And of course we wanted to get back to the States, but at the time we knew that that was an impossibility. We weren’t heading that way. So we were put on a train, went for several days, I guess. I can’t tell you exactly how long it took us. In between we did go to what was called an interrogation center which was called Dulogluft. Dulog I think means interrogation, Luft means air. So it was meant for the Air Corps people. And there you were told that if you didn’t answer the questions, they were not going to notify the International Red Cross that you were a prisoner and what your physical condition was. The Geneva Convention was not something that they adhered to at all.

PRINCE: That’s name, rank, and serial number?

SABOL: Yes. It’s what we were supposed to – that’s all we had to give, but they wanted more from you because the more information they gathered about the groups – how many planes, where you were based – you know, whatever they could get from you. But sometimes it worked out that they knew more about you because of past experiences. So they would take a dog tag from you and leave you with one. And the one they’d take was the one they were required by the Geneva Convention to turn over to the International Red Cross, who in turn notified – the American Red Cross, who in turn notifies the State Department or whatever. I forget exactly where it goes to. And then they send out the telegram, “Missing in Action,” you know. So we went there. I don’t know how long we stayed. Whether it was a day, but I can’t remember those things. And then we were put on a train to go to our permanent, supposedly permanent camp which was called Luft 4.

PRINCE: Luft 4?

SABOL: Luft is air, 4, and it was very, very far north, and the information that I could understand was that it was sort of a new camp. It was pretty close to Poland supposedly and it was in the northern area of Germany. We were watched much, much more closely, the Air Force was, because we were told certain escape routes, how to escape, where to go, who to look. I mean they gave us a lot of information. They told us a lot, as much as they could tell us. They had to withhold something from us because if we ever started turning in those people, it would shut off escape routes and with serious consequences. And since we had an escape packet which was immediately taken from you anyway, there was all kinds of things in there – maps, money, all kinds of things to help you get away, if possible. It proved to be some use to some people, but in our particular case it was useless. And, of course, we didn’t have it anyway. When we got to the train station, we lined up – you know, you do everything they tell you to do.

PRINCE: Had you gathered more people?

SABOL: Oh yes, yes, yes we did. I don’t know what the numbers were, but we did definitely come in to more people – 50, 25, I mean it’s hard to – I can’t give you numbers. I can’t tell you that. Too many things happened that it was just a – it was a trying time. And we were either tied together, chained together or something two by two, and we started walking up to the camp. I guess that’s what we were doing at the time. We didn’t know what was – you know, you’re not told anything. You don’t ask anything. You don’t talk anything except among yourselves, you know. It’s a discouraging situation because first of all, nobody’s going to give you the food and the water and the comfort, the things that you need for everyday, you know. So we start walking and we see a – well we found out later what happened – the German officer comes down and he’s telling the Germans who are leading us, he’s getting pretty irate with them because he said, “We have to run to this camp. We can’t walk.” And he said, “These dogs will help them along, to run,” you know. But fortunately, we were almost there and we find out later that in other instances some of the men were bayonetted and some were bitten by the dogs. This particular officer, whenever he could get there and knew that men were coming in to meet them – he happened to be an SS officer with the rank of Captain. The officer, German officer in charge of our camp was a Major, but he was an army officer or he was in the Air Force, he was an Air Force officer. But the SS people told them what to do, and he was a – he made life more miserable for us, this officer, SS officer. We got to the camp and there were four what’s called compounds, four different areas fenced off and far enough away from each other. You could see – you might recognize somebody in some of the areas, but it was, you know, pretty large areas. We wound up with 10,000 people there. We opened up – we were the first to go into this, called Lager D barracks on two sides. And I don’t know how many barracks were in each compound, lager, whatever you would call it, or how many men. But the rooms were very crowded. The facilities were – there wasn’t any. It just wasn’t there.

PRINCE: Did you have the stacked beds?

SABOL: Yes, yes. I think they were two high, to the best of my knowledge. What we possibly could have start getting a blanket or something, I can’t tell you, you know, about as far as what were material things that were issued to us in the beginning there. Where we first got them and what we did and everything, I don’t know because some of our fine equipment was confiscated. You know, whatever they wanted, they took, you know. If you happened to be wearing or have a ring or watch or something, those things were always gone, you know.

PRINCE: So at this point you had nothing of your own.

SABOL: No, nothing of my own.

PRINCE: Just your –

SABOL: No, nothing. If I had a wallet – I don’t even remember.

PRINCE: Whatever you had was gone.

SABOL: Oh yes, everything. No, your pockets are cleaned. If they wanted certain flying equipment that you were in, if they wanted it, they took it. And we got to this barracks and as we came in some more of them started coming in, little by little. It started filling up. Every day there would be more, you know. On one side of our particular compound were people from the Royal Air Force. Those people were from New Zealand, Australia, England. England, defected Polish, or anybody who flew for the Royal Air Force, they were on – how can I say? They were occupying the other row of barracks opposite our row. And we got along famously well.

PRINCE: All enlisted men?

SABOL: Yes – I don’t think there was any British officers neither. But they were prisoners much longer than we were. One of the incidents as I can remember is that someone was sort of honored, you might say, at a roll – when we were all out. He was given some kind of a (LAUGHTER) – my recollection was a big Spam key. I don’t know what it was.

PRINCE: A Spam key?

SABOL: Yes, something to that effect. He was taken at Dunkirk.

PRINCE: Oh my heavens.

SABOL: I think it was about five years they were there, you know. But they were a hearty group of men, really hearty – tough, sociable. We got along very well with them, no problem.

PRINCE: And you could fraternize with them.

SABOL: Well there was a degree of that, yes. I mean, you know, you sort of, you had your place such as you knew your barracks. You sort of formed a little group or pool of people that you were with most of the time. You sort of stayed close to one another. There was some – they played ball a little bit. We had a long area we could walk around, a pretty good sized area to walk around in, exercise. And there was a warning wire which was a low type thing and that was about 25 feet or so from the barbed wire and the guard towers at four corners were watching and it was strictly against regulations to touch the warning wire. For any reason that you had to go over there or go near it, if you didn’t get permission, you were automatically shot at. And we were told this and this was a fact. Anything that they told you, you certainly believed and they made a believer – I mean, you knew right away. So we tried to, you know, do as they told us to do. You have a question?

PRINCE: Was there any anti-Semitism towards you from your own people –

SABOL: Yes, yes.

PRINCE: – in the Air Corps?

SABOL: That was the reason why I didn’t associate very much at all other than sleep and eat in my room. I went to another room where there was a number of people who were prisoners longer than we were, by the way. Many of them were Jews, Italians and other – Irish – a little bit of everything there. A very mixed group of boys, fellows.

PRINCE: How did this anti-Semitism show itself?

SABOL: Well, the word “Jew” always came up, the cause of the war and for a number of reasons. If the weather wasn’t right, I guess it was the Jews’ fault, whatever. The reason they were there, perhaps, maybe because of the Jew. It showed itself. It was there. And it was very disheartening, very disheartening to have it come from your own people, and you’re all in the same box with no place to go. But it was there.

PRINCE: It must have been very difficult to take.

SABOL: Well, so you overlooked – again you overlooked it because, first of all – so you could speak out against it, you know. Naturally you could do that. Who are you going to fight? I mean, are you going to fight 20 people?

PRINCE: Who’s got the energy?

SABOL: I mean, you know.

PRINCE: Did you have any from the Germans?

SABOL: No, I can’t say. The fear was always there, always present. We talked amongst ourselves, the Jews, because we didn’t know – we thought we knew what day it was but we weren’t sure when our religious days were coming and whether we could do anything. You know, we couldn’t hold services. There was nothing we could do to celebrate our religion without question. We just talked about it amongst ourselves but we knew. It was something that we were aware of – that there was problems. But under the circumstances, we were very limited as to what we could say or do.

PRINCE: Did you find Jews that weren’t interested in what day it was? Holiday, or anything and just really wanted to be –

SABOL: Yeah.

PRINCE: – left alone as far as their religion was concerned?

SABOL: We – it wasn’t a priority, I guess. We knew we were Jews. There was no question about it. I mean, I didn’t deny it. The mere fact that I didn’t throw my dog tags away and didn’t throw that prayer book away because I felt that if I was going to go to the grave because of my religion, I could not think of a better or more appropriate reason to do so because of being a Jew. And to me that was extremely important. Although, I got to admit – later on you’ll find out, maybe – that you do lose faith in everything, everything, everything – (VERY SOFT, LOW VOICE) – everything, you really do. And trying to appreciate your Judaism – you know, just do what you could, it was – I think there was some – on occasion there was some religious services, whether Protestant or what. There was times when we could have been visited by the International Red Cross to see how our conditions were and if we had any complaints (LAUGHTER) or anything. But, far be it for us to complain, you know.

PRINCE: You’re laughing – explain.

SABOL: Yeah.

PRINCE: Why are you laughing?

SABOL: Well, it’s hard to explain. The actual condition, the actual feeling. You can’t read about it, you can’t – unless you were there, I mean – there was a certain way of doing things in order to create less of a problem because you just fell down and lied. Really, I mean – what good would you do if you did complain?

PRINCE: And then they created in turn certain things that you knew you had to do, so that they created less of a problem. In other words, you knew that if you touched the wire you would be shot. You knew that. So you just made life as bearable as –

SABOL: Yes, yes. Because they controlled it. They controlled everything. They had the control over everything.

PRINCE: Tell me about your day.

SABOL: Well, the first thing you did – I don’t remember what the time it was. They would wake you up and you’d stand in front of your barracks.

PRINCE: How did they wake you?

SABOL: Well, “Raus, raus,” I mean, they had their favorite words, “(Loess),” “Schwein.” They had all these –

PRINCE: Haus means out.

Tape 2 - Side 1

SABOL: We’d line up by our barracks and they would count us. One of the worst things the Germans are able to do is count. I don’t understand why, other than the fact that maybe we would keep weaving back and forth and back and forth (LAUGHTER) and they could never, never count us. But consequently, we were only hurting ourselves especially when the weather was bad, it was raining or whatever, you know. That meant we were there until they got the count that they were looking for, you know. And it was a favorite of ours (LAUGHTER) to move in those lines. It was really pathetic. They could not count! And to add to the problem, (LAUGHTER) the lines would keep shifting back and forth.

PRINCE: So you resisted.

SABOL: Oh a little bit, you know, and have a little fun, you know. And we’d try not to show any – that we were doing this on purpose. We tried to do it in such a manner that they didn’t know what was going on. And after that, then I guess we might have gotten something, ersatz coffee or something. We were, to the best that I can recollect, is that we were supposed to have received one Red Cross parcel a week per man. That’s what I can recall. But they never adhered to that policy. We – we were constantly dividing a package amongst the whole room maybe. And if there was an issue of bread or anything, article of clothing, the first thing was said was, “Get the deck of cards out.” And through the deck – if you got a loaf of bread, they cut it up into a piece for each man, but you couldn’t get that loaf of bread until you put a – I don’t know how – we did it with cards. We had to draw a card or something. I don’t know. Everything was done with cards.

PRINCE: This was by you all?

SABOL: Yes. Because it was impossible to cut that bread even for everybody and-

PRINCE: Oh, so then you picked –

SABOL: – divide it up –

PRINCE: So if you got number one, you got first choice, or number two?

SABOL: I don’t even remember that. All I know is that the deck of cards was always on the table when something came in. Sometimes if you got two or three sweaters and there’s 20 people or whatever, there had to be a method of doing this. The only way, the only fair way they could figure out was with the cards.

PRINCE: Did there just assume to be a leader? How did that work? Who?

SABOL: There was supposedly a barracks leader and there was a compound leader and maybe a camp leader. I think maybe it was sort of that way. Because if any information or anything was sifted on down, at lockup time at night is when – if they heard anything or they knew anything, everybody would go into the aisle of the barracks and you were told what they heard. Whatever news, if a Red Cross man was coming – I mean, just all kinds of things. Supposedly they had a radio at this camp. I mean, I never saw it. I don’t know. And news would come in or something. Someone could read the German paper if they got ahold of one, or something. Things were always –

PRINCE: I’m sorry I distracted you. You were telling me about the day.

SABOL: That’s okay.

PRINCE: Okay. So you were dividing food.

SABOL: Yes, whatever came in, and during the day, I think the first thing we got was this supposedly coffee. It was ersatz, something ersatz, artificial. I think that’s what ersatz means.

PRINCE: Yes, sometimes it was made from turnips and things like that.

SABOL: Whatever. Because the butter and the jam was supposedly ersatz too, or something, you know. And then, what did you do? You associated with some of your friends, maybe walked around, and I can’t tell you exactly what we did do.

PRINCE: But you did no work?

SABOL: The Air Force was never allowed out of the camp, was not allowed to do any work, to go away, because they were more informed about escaping and were – previous experience had showed them the people who were escaping from the camps were the Air Force. Always Air Force people ‘cause they were better equipped. Infantry just did not – they did, I’m sure, escape at times, but Air Force people tried it more often. It was considered an American sport and then after a while it got to be where they said they would not tolerate it anymore. Anyone trying to escape would be shot at. Everything is, “You’re going to be shot at.” That was the bottom line, and we only had one attempt from our camp. We were in a forest area, no towns around. It was probably one of the best guarded camps and I don’t think anybody ever got away from them. There was no place to go.

PRINCE: So what happened to them?

SABOL: To the rest of the day?

PRINCE: No, you said there was one attempt. Did they make it?

SABOL: No, no, no. We had latrines and I might say that there was a barracks, one barracks that I can recall that was away from our area. We could see it, and it was Russian prisoners. This is what we could see. And they received some terrible, terrible treatment. You could see beatings going on there without question. That I’d seen. One of their jobs was – we called it the “Honey Wagon.” It wasn’t the Honey Wagon – what they would do was pump out the latrines. We had an outside latrine. And one of their jobs was that. I think we could have had, at lockup time we could use an emergency, something in the barracks, a latrine.

PRINCE: A barrel or something?

SABOL: I don’t know what it was. I don’t even remember anymore. I don’t remember. I think it was a washing area and it could have been to relieve yourself there.

PRINCE: Did they lock you in the lagers?

SABOL: Oh yes! They, they – yes, you bet. In the barracks, they closed the shutters and the doors had outside doors that they locked, and they patroled them at night with dogs and searchlights. And while they were – a barracks next to us or something, I think it was, this so-called “Honey Wagon,” it happened that one of the wheels fell down in a soft spot (LAUGHTER) and the Germans right away suspected something, and I can still see them coming down and everybody in that barracks were made to get back in. They nailed up the windows, the doors and everything. And they checked it out. There could have been the starting of a tunnel. I’m not sure. But nobody went anywhere. There was no place to go because that was the only thing, the closest we got to get.

PRINCE: Since they had nothing for you to do during the day, –

SABOL: There was some ball playing.

PRINCE: That’s what I was going to ask you, did your own people organize sports and exercises?

SABOL: Well, not so much exercises, maybe walking around and there was a ball or two if you wanted to play ball.

PRINCE: They never organized exercises to keep you in shape?

SABOL: No, to the best of my knowledge, I do not recall any of that. Playing cribbage which was an English game you learned how to play. Some of them played bridge. They made checker sets on the table. They just carved out. You know, the Yankee ingenuity is a very, very famous thing. Unless you come in contact with it, you can’t believe what these guys could do.

PRINCE: I’m glad to see you smiling now.

SABOL: I’ll tell you. (LAUGHTER) Well, Yankee ingenuity comes up with things. I mean, you know, it was just fascinating, the things that they could do and everything. Course, one of the sad parts was this tunnel thing. The SS officer found about it and he calls everybody out for another roll call. And he says that no longer will it be acceptable for any tins that we use to – any coffee tin, can or whatever comes in – you get a little meat or something – can be kept. We must turn these in every day. And he said that if we don’t live up to his way, what he wants us to do, he said, “This compound will be littered with American dead.” So immediately, everybody ran to the barracks and pulls out, if they had tins or anything, any cartons or anything. We started turning them in immediately, because we knew that this guy was – he was fearful and we really dreaded him. So, we listened to him and did what he asked us to do. In the evening we’d get a bowl of soup or maybe a potato. It was always – you never knew what was coming from one thing to the next. It was bare minimum rations.

PRINCE: Was that your only meal, or did you get –

SABOL: No, that was it, that and the coffee in the morning. One of the problems being, each room was issued a metal bucket. And the metal bucket was to be taken up to the mess hall and they would put in the dehydrated vegetable soup which, by the way, contained maggots, and when they made the soup, they blew up and had gotten big, and it was disasterous, difficult to eat. Most of the meals was very little. Rarely did we get meat. I’ll tell you, I ate anything and everything I got at that point. I was not about to forego anything I could eat. I was going to eat. And the problem was that this one bucket served for getting the meal. They also had other things. Each person was put on a list as to when they would get a bucket of warm water to wash their clothes or shower or what. Everything was done in this one bucket. If you missed your turn, that’s too bad. But you wanted to make sure that you had that bucket ready when it was time for you to get your food. It had to be cleaned and ready to go. And, of course, we did try to keep our place clean, like wash the floor out – these buckets served everything but a toilet, if you want to know the truth. They could have served as that too. And we tried to keep it clean. We tried to keep ourselves clean. I mean, we did the best, you know, under the circumstances. Washed the best we could, and our clothes. And we took care, pretty good care of ourselves, under the circumstances.

PRINCE: How were you all to each other? How did you all treat each other?

SABOL: Well, I would say, with the exception of some of those who were so antisemitic – you didn’t associate with them. You spent as little time with them as possible. I would say the treatment – you know, it was good. We were friendly, we were close. We shared our ideals and we just talked and we just got along fairly well.

PRINCE: When there was anti-Semitism towards you or towards the others, how did the other people react? Did you find that they stood up for you or stayed out of it, or both?

SABOL: You just went away from them.

PRINCE: No, what did they do? What did the others do?

SABOL: They were very – you know, they – I think they sort of sympathized with the other people, more so than you. They – in the same room. When I went to this other group of people, without question they stood up, because of race, religion, creed, whatever.

PRINCE: But your particular group just –

SABOL: Room – assigned to –

PRINCE: – room was not just very warm towards you?

SABOL: Without question, yeah. The other one was the complete opposite. We used to really go crazy with each other. I can’t tell you. I’d be ashamed to tell you some of the things we did because you (LAUGHTER) can’t believe what the mind will do when it’s locked up like this.

PRINCE: I’d like to hear about anything you care to say and I would try very hard to understand what you had to say.

SABOL: It was a close association.

PRINCE: Did you – would you like to talk about anything?

SABOL: Well I don’t think they’d be all that interesting, to tell you the truth. As winter came on, we got to feeling the weather. I thought we’d start in August which was not too bad. The warm weather we could take, but as winter came on, we – it was pretty bad. I don’t recall a stove in the barracks at all. I do not recall seeing a stove. If we had a stove, I don’t know what we could have burned, what we could have used. And it was getting – starting to get difficult. Sometimes you wouldn’t shave, you’d grow a beard. Sometimes you could see when you walked around outside, the moisture would freeze if you had a beard or a moustache or something. They did crazy things like cuttin’ their hair in crazy ways. And I used to say, “Man, those guys are crazy. Why would they – ?,” you know, used to keep saying it and saying it. And one day I was coming in the back. I think I had two buckets of water or something. I don’t know what I was doing. And they grabbed me and made out like they were cuttin’ my hair and I said, “Well, I guess you might as well cut it all off.” And they did! And they shaved it and all. And this was getting into winter and it snowed and was real cold, and it was crazy. But we did some foolish things, you know.

PRINCE: Well –

SABOL: It was a time when you’re trying to not consider your situation and, like you talked when you get home, like what are you going to eat and what you’re going to do. I mean, it was just crazy.

PRINCE: You did talk about that?

SABOL: Oh we talked about going home, and one guy was going to eat a pie a day and one guy’s gonna buy the biggest car – I mean, it was crazy, crazy – girls coming in your mind and, naturally, you know, things of this nature.

PRINCE: Sure.

SABOL: Boys talk about those things, you know. And it was just difficult to tell you a lot of things because – well, some of the things I don’t remember.

PRINCE: Could you see some people changing and becoming someone else entirely?

SABOL: Well they were, I would say, they could have been a little bit more irritable. There was a time when they said that some of the wounded would be repatriated and it made us feel kind of sad in a way. We were happy for them and we were not so happy for us because we were staying and they were going. And then we started hearing the things about – I don’t remember exactly when the breakthrough, the German breakthrough came about. When they broke through the lines, the American lines with a certain offensive. What it was called doesn’t come to my mind right now.

PRINCE: You’re not talking about Bastonne?

SABOL: No, no, that was a different thing altogether. This was where the Germans captured thousands and thousands of us, there were Americans, cut them off, surrounded and really – it looked like they were startin’ to win the war again. It was some kind of offensive and when we – when the news came to us, it was very disheartening because our hopes were high. We knew that they were being hit quite a bit because not too close to us, we could hear some of the bombs at night. The English used to come at night and the Americans flew only during the day, only day missions. English would not fly at night. They weren’t –

PRINCE: They didn’t fly in the daytime, you mean?

SABOL: Yes, they only flew at night. They thought they were safer at night. That’s just the way they felt. They – very rarely did they pull a daytime raid. Only the Americans were flying daytime raids. And we knew – and we got information that the Americans were winning and this and that and everything. And then we hear this terrible news of the breakthrough. I’m trying to pinpoint the time and what it was called, the offensive, because it was a very – you would know if I told you. I’m sure you would have heard about it. (SIGH) And then –

PRINCE: You talked about you were moved.

SABOL: We what?

PRINCE: You talked about you were moved.

SABOL: Yeah. Towards some time in January, I don’t know when it was.

PRINCE: This would be January, 1945?

SABOL: Yes. We could hear – there was a lot of air activity and there was a lot of big guns. We could hear rumbling. We knew things were going on. We could hear it. We knew it. And one evening after lockup time – and I can’t tell you how this all came about because I don’t remember everything, they said, “We’re gonna move.” The weather – well, what was it? Below zero, three, four feet of snow on the ground and we’re gonna be moved. And you talk about 10,000 people going on the road. How do you take care of their food, their water, their clothing. You just – it’s difficult. And why this is so – why I have a problem with this is the fact that I always relate, in my own mind, I rarely tell anybody. If you can picture yourself in with cattle. Do you know how they used to move cattle? But you’re the cattle. And this is how – it came to me immediately, “We’re gonna be driven like cattle.” And I knew that – this was really, really hard to imagine what we were gonna be faced with. And as time went on, I said, “Maybe we better start storing some things, got an extra candy bar, an extra can of meat or something. Maybe we better store toilet paper, anything we can start putting away.” Then we started sewing masks for our face and something to carry the little we could leave with. We started preparations little by little, not to let them know what we were doing. But we tried not to let them know. It was just like being hit by lightning. And then as it got closer and closer to us, our feelings – you know, “What are we going to do? How are they gonna handle this? How are they going to take care of this situation?” As things were bearable at camp, although you weren’t getting what you should be getting or what you really needed, we could cope with that. We learned to cope with that. But when we knew that we were going to move, it was something that – it was hard. I can’t tell you. I can’t explain it to you. The first day, morning, whatever, we get out on the road. The first of February and it was just lined with men. They let 2500 of the wounded or at least able to carry on, go on a train to some place. We don’t know. We weren’t interested. So we get out on the road and the German soldiers were Air Force too, by the way. Still our guards were Air Force, and dogs and guns and everything. It’s all they had. We couldn’t see any food preparations, no nothing. And we start walking. The snow on the ground was our water. What few things that I had saved up myself, at the first break my good friends threw everything away ‘cause I couldn’t carry. They said, “You can’t make it and you can’t go. You got to get rid of everything.” I carried a blanket and that’s it. Couldn’t. I can still see the things flying through the air, cause they just couldn’t do it, couldn’t do it. Was exhausted from the very first break and it was cold. It was cold – you don’t know. It was very difficult. And I tell you, I don’t want to tell you too much about that ‘cause it’s – it wouldn’t be interesting to you.

PRINCE: I don’t want you to do anything that you –

SABOL: No, you wouldn’t, you wouldn’t.

PRINCE: I don’t want you to do anything that –

SABOL: You wouldn’t want to – I mean, it’s not helpful in any way and I might highlight a few things for you on it, but then I’m not gonna talk about it.

PRINCE: Uh-huh. That’s enough. I don’t want you to –

SABOL: I don’t talk about it unless you were with me, you know?

PRINCE: Right. Allen, I appreciate your doing this. I appreciate your wanting to. Is there any way that you would like to end this up?

SABOL: Well I think we’d have to maybe go into another session because I think it’s time I –

PRINCE: Okay.

SABOL: I don’t know how interesting they’ll be to you, but I thought, “I’ll just bring them.”

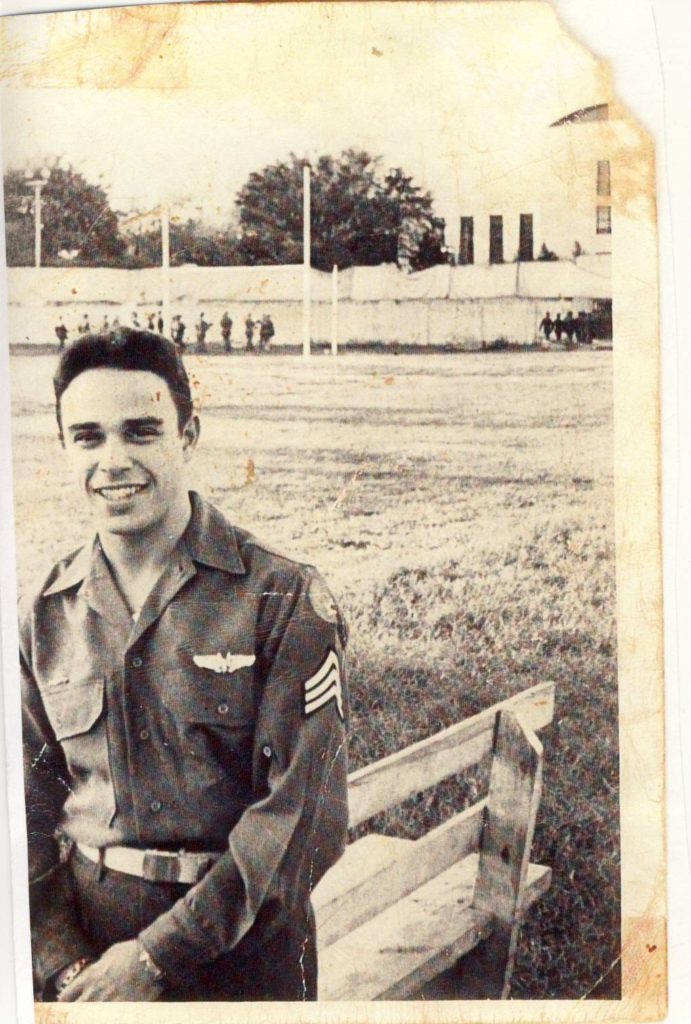

PRINCE: This is our second session and it is July 26 and I’m talking to Allen Sabol. Okay. He’s showing me pictures.

SABOL: This is a picture of four people, as you can see. And this particular one was one of our guards on the road. That picture was taken up at the Russian front and he gave me it.

PRINCE: Well who is who?

SABOL: They’re all German soldiers.

PRINCE: Oh, I was going to say it’s not you –

SABOL: No, they’re all German soldiers. He had that picture taken and gave it to me –

PRINCE: Where did he get it?

SABOL: Where did he get it?

PRINCE: Because they’re happy with guns.

SABOL: Well (LAUGHTER) they might have been winning that day. That might have been a day they were winning, and there was times when I thought I would try to contact him and everything, and –

PRINCE: Well he got this – he got this off of a German.

SABOL: Yes.

PRINCE: A dead German, probably.

SABOL: Oh no, no, no, no, no, no – no, no. The picture is of him.

PRINCE: Where is he?

SABOL: This person right here.

PRINCE: That’s him?

SABOL: That’s one of our guards that we had on the road. He had that picture taken when he was up on the German front, transferred to another area at different times and finally wound up being one of the guards that guarded us as we left our camp.

PRINCE: Now is this a German?

SABOL: Oh yes. Oh yes, yes, yes.

PRINCE: Does it look like he has a gun?

SABOL: (LAUGHTER) Well – believe me, they’re Germans, Nazis, Germans, whatever you wish to – there was one or two that we sort of communicated with a little bit.

PRINCE: In what way?

SABOL: Well we were able to talk to them. Most of them we didn’t. We really weren’t supposed to fraternize, there was no question about that. Fraternization was not the thing to do. First of all, if your own men saw that you were getting too friendly and maybe getting some extra food or something or telling them something, you know, it didn’t look good. It wasn’t proper. But there was one or two that we did talk with and he gave me that picture while we were on the road.

PRINCE: Oh, this was on the march?

SABOL: No, no. That picture was taken on the Russian front while he and those others were –

PRINCE: Was he still fighting?

SABOL: Oh they were fighting, oh yeah. I mean, that was just a lull in the battle or whatever, you know. (LAUGHTER)

PRINCE: I don’t get it.

SABOL: That was the battlefield, I suspect. That’s what a battlefield would look like.

PRINCE: I’m just trying to piece it together and I see them being friendly, so –

SABOL: Well there were a couple of them that, you know, that you could talk with. Nevertheless, they knew who they were and we knew who we were.

PRINCE: It’s like they’re looking at something.

SABOL: Could be, could be. That’s possible, possible. Just perhaps a lull in the battle and I’ve kept it all these years. He wrote his name on the back of it, I think where he came from and I made some halfway attempts to maybe reach him or something, but I suspect that would be next to impossible at this time to even come close to finding him. And I don’t know that I want to anyway, anyway. This was our identification card and this gives you your army serial number, you name and your rank and the group that you were with. I thought I might have had our prisoner of war number on there, but it may have it on the other side. I’m not sure.

PRINCE: “Issued at Allied Prisoner of War Camp.”

SABOL: Uh-huh.

Tape 2 - Side 2

You know, I really can’t tell you because my –

PRINCE: (READING) “This is an Identity Card for Ex Prisoner of War, Prisoner of War Camp. Paymaster: This Identity Card must be retained until collected at the reception center in the United Kingdom.” Were you shipped to –

SABOL: No, the British were the ones that liberated us and during the process of getting to different places, and one thing after another, it’s possible they gave us that. I think they gave us some money.

PRINCE: It says, “Issued at Allied Prisoner of War Camp, May 3, 1945.”

SABOL: Really. I just kept it and never really read too much about it. This is our crew, with the exception of the officers. There are six enlisted men and four officers.

PRINCE: Oh my, is this you? Is that you?

SABOL: Believe it or not. (LAUGHTER)

PRINCE: Really – cute!

SABOL: Well, you know, one does turn gray after a while. (LAUGHTER)

PRINCE: Ohhh.

SABOL: (LAUGHTER) Yeah, uh-huh. And that’s our group, that’s our group.

PRINCE: There’s always a tall – he must be from Texas?

SABOL: Let’s see. That’s John Harper and he’s from West Point, West Virginia, if I’m not mistaken . I should know his address ‘cause he’s one of them that I do communicate with. Should know his name. I think three to four of them have passed away.

PRINCE: Where was this taken?

SABOL: If I’m not mistaken, I think that was taken at Pueblo, Colorado when we were taking our – it had to be, yes. Either there or it could have been Topeka, Kansas, our staging area. But I think that was at Pueblo, Colorado. We were just finishing up from training. This is –

PRINCE: There are six of you.

SABOL: Enlisted men and four officers. There’s ten to the crew in the type of ships that we flew.

PRINCE: And this is war prisoners’ reunion. This is from a newspaper. It was a scene from a skit at a reunion in downtown YMCA, former prisoners of war in Germany. Are these all St. Louis people?

SABOL: Oh yes, yes, oh yeah. We had quite an organization going. We had quite a few people in it. It was rather difficult to keep it going ‘cause, after all, none of us had the experience of this type of thing, but the prime purpose and the only purpose of it was – it wasn’t a social organization, it was meant to be an organization to help the men get the sort of treatment and attention that they had been denied. You’ve got to remember, when all these thousands and thousands and thousands of men come pouring out of these camps from both sides of the ocean, the government was not prepared to handle them and take care of their needs without question. They didn’t know what to do with ex-prisoners of war until Vietnam. And that was a very sad thing. They just didn’t know how to cope with it and consequently a lot of people were denied treatment, were denied compensation, things that they should have been given that were due them, you know. Although we did get a number of things, one thing was we were allowed two weeks of a “call it what you want” – you take your parents, or if you’re married your wife and they send you to a resort for two weeks, all expenses paid for everybody. I mean a complete two weeks. You just go for two weeks and do what you want to do, and the government picks up the bills, which was very good, good therapy. I think what it did, it let the men know that they were free and it showed some sort of compassion, you know. It was helpful. It was very good.

PRINCE: What is it? What did you want?

SABOL: What did we want? Well, first of all, mentally you have to know how to cope with this kind of thing. You have to know how to handle it and –

PRINCE: Now let’s go to where you would like to go, which is to the liberation, when you were liberated. Who liberated you?

SABOL: It was the British.

PRINCE: And can you describe a little bit how it happened?

SABOL: Well, we were told that – actually, we were told we were surrounded and we were to allow – the Germans were going to allow some of our people to try to make contact with the British. I can’t say that this was done or just what was done, but I know – and what time of the day it was, I don’t even remember that anymore. But we hear some noise, and down the road comes British tanks, a number of British and some of their mechanized equipment, and they tell us we’re liberated, and they do have a place for us to get some food but they have no facilities to get us there. We must continue on to go. The Germans disappeared. I can’t tell you what took place with them. I don’t know where – I wasn’t interested. When we heard that there would be food and shelter and things for us, that’s – so we just made a mad rush. “Tell us where to go, how to get there,” you know.

PRINCE: Uh-huh.

SABOL: And somehow another, we found it. I don’t know how we found it, but we did. And it was very exciting, it was very traumatic to know that at last you would get something to eat.

PRINCE: At last.

SABOL: Yes. Something to eat was very important.

PRINCE: Do you have anything that you would like to pass on to people, children or adults that might listen to this?

SABOL: Well I guess it would be the fact that even though you read about it and you hear about it, it’s hard to comprehend what really takes place. The thing I would be happy about is that it never happens here and that they don’t have to – hopefully, they will not have to witness this kind of thing. Fortunately, our country has not been involved in that aspect of the war, but we would not want them to forget and would like and hope that they would understand what did take place and appreciate what other people had gone through and hope that whether that would help them prevent another war or whatever. I’d hope that this in some way, shape or form would be a lesson for them.

PRINCE: Well, I would like to thank you for what you’ve done then, and the fact that you took the time to relate it because I think it is important. But I don’t think, as you’ve said so often, I don’t think anybody who hasn’t been through it can possibly conceive of what it is, and I’m sorry that it happened to you, and thank you for telling us.

SABOL: Thank you.