M: This Marge Bilinsky interviewing Rudy Oppenheim on the 20th of February, 2004 on the Chevra Kadisha Ohave Sholom of St. Louis.

M: Rudy, first of all, tell us your name and spell it for us.

R: My name is Rudolf Oppenheim, also known as Rudy Oppenheim, R U D Y.

M: Rudy, what is your title with the Chevra?

R: I am the President of the Chevra Kadisha Ohave Sholom.

M: What does that mean?

R: Organization of Brotherly Love.

M: How long have you been it’s president?

R: Since 1969, 35 years.

M: And tell us how the Chevra was formed.

R: The Chevra was started in 1937 when the German Jews started to come to St. Louis

when a group of German-Jewish refugees, fleeing from the Nazi persecution, decided to form a congregation in St. Louis. Their aim was to share a commonality of being uprooted by the Germans in Germany and having to start over in a new land.

M: Do you know who their first officers were?

R: Yes, I do have those. The first officers were Sigmund Falk, one of the founders, Max Gottschalk, Philip Philipsborn, Ludwig Oppenheimer, Ernest Goldschmidt.

M: Why were they formed and what did they do? What was their purpose?

R: The Chevra started out as a Self-Aid to help those who were coming over. As more and more refugees began to arrive in St. Louis in 1938 and 1939, the organization functioned as a Self Aid by helping new arrivals to find places to live and to obtain jobs. Cultural evenings were held in the old YMHA (later the JCCA building) on Union Boulevard, consisting of lectures on Americanization and other adaptive techniques for settling in a new country. Since many of the new arrivals did not speak English, most of these events were held in German. The organization also sponsored classes for learning English.

M: That was Night School, right?

R: Yes, Night School right.

M: We used to call it Night School. How many people were in the Chevra in the beginning?

R: In the beginning, there were close to a thousand if not more of membership.

M: What year would you say that was?

R: 1940.

M: And how many are in the Chevra today?

R: Today, the Chevra, of course, is a dying organization. There are about 80 to 90 members

M: Was it for socialization, kind of a way of getting to know each other, too?

R: Getting to know each other. An important issue here, was that this group was that of a religious involvement in the community. The St. Louis Jewish community at that time did not really attune itself to the problems of the arriving German Jews. Even though, the early founders of the St. Louis Jewish community were of German heritage, the later influx of Russian and Polish Jews at the turn of the century, created a dichotomy in religious commonality in St. Louis.

As a direct result of this, the German Jewish refugees decided that it would serve them better in their adjustment to life in America, if they would hold their own religious services, at least for the High Holidays. Consequently, they began to hold the Rosh Hashana (New Year holiday) and the Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) services at the Berger Memorial Funeral Home. The late Henry Berger, through his generosity, made his facilities available at no charge for the three days. Further, he established a special reduced pricing of funeral services for the refugees.

M: Are there written records for the Chevra and where are they located?

R: I have all the records for them.

M: You have that. Did the Chevra ever split? Or did they always get along together

And do everything together?

R: It’s an interesting question you pose here: of whether it split? It didn’t really split. It is a story that goes back to 1942-43. A that time when the Chevra decided that perhaps they would form their own congregation and build their own synagogue, some of the members felt that we shouldn’t be split away from the American Jews and Russian Jews. As a result of that the synagogue was never built And all the younger members of the congregation who had children joined other congregations where they would have Sunday School and Hebrew School.

M: When was the last service at Berger held:?

R: 1964

M: Who conducted the services?

R: It was conducted actually by a Hazzan, not a Rabbi but a Hazzan, Manfred Isenberg

And Mr. Isenberg was a professional cantor and he was also trained in rabbinic knowledge, so he delivered the sermons in German. The congreegation met there. I wish I had recordings of those services. It could have been easily done and then you would have had all different types of melodies or nygun from all over Germany harmonizing. They were beautiful. The service, by the way, leant more towards the Orthodox than to the Conservatives than the Reform. So that many older members wore their white kittels to the service.

M: I bet it was a sight. Did the children participate in any way at that time?

R: The young people, at that time, would come to services, but many of their friends were in other congregations (garbled).

M: Was there a Rabbi ever?

R: For a short time there was a Rabbi Appel, Rabbi Appel was an older Rabbi, retired rabbi. He was a retired rabbi. He was from Germany and he once in a while he would come by and deliver a sermon. We sometimes had a guest rabbbi. .the late Rabbi Robert Jacobs at one service, one Friday night service or one evening service during the holidays.

M: Can you think of any other memories you have as a small boy going to those services?

R: Oh yes, absolutely. One thing is we walked a mile and a half from 5500 Pershing to Berger Memorial. And that included my Grandmother who died at the age of 94, so she was already in her eighties and ninties and she would walk to services.

M: Did the kids congregate outside and did they ever get in trouble?

R: Well that is normal. You always find that in congregations.

M: What temples and synagogues did they join at that time?

R: They joined Temple Israel, Shaare Emeth. They joined Brith Sholom.

M: Was that because they had other family there?

R: Those who wanted Reform joined Temple Israel or Shaare Emeth. The conservatives joined Brith Sholom.

M: You mentioned you walked from a certain area…was there a certain area that the German Jews lived in in St. Louis?

R: For the most part the German Jews lived in the 5500, 5600 block of Pershing and Waterman and the 5700 block of Kingsbury and Westminister. I know that area well

Because as a youngster in June and July I would ride through those streets selling Jewish New Year’s cards or taking orders for Jewish New Years cards for the Friedman Brothers

In St. Louis.

M: They didn’t live in the Goodfellow or Belt area?

R: A number of them lived in the Goodfellow and Belt area but not too many, but for the most part the German Jews lived in the lower section.

M: What kind of work did most of them do in that time when most of them were immigrants?

R: They did every kind of work imaginable. The Kaufman family were in the bakery business. They baked the Selka chocolate cookies. The Levys were in the shoe finding

Business. Other people found jobs whereeer they could get jobs. They adapted very well.

M: Are there any others that you can think of …people in the German community…what other bussiness they were in?

R: There were people in the garment industry and there were people in kind of day-care, specifically for people who went to work at the company as accountants, as bookkeepers

And there were doctors too.

M: Did the women work?

R: Yes, my mother worked for the dress factory.

M: Did they take an active part in other Jewish life in the city, like the Federation?

R: Not so much in the Federation. The Federation at that time was out of their perview.

M: But other Jewish life? What else did they do?

R: They perticipated in synagogue life. Those who went to temples and to Brith Sholom, later on were very active in those organizations.

M: Was there anyone outstanding in the Chevra who did participate in St. Louis’ politics or social life?

R: Yes, there was Fred Mishow. Fred Mishow was very very active in the Democratic Party and.even ran for Mayor of University City.

M: Was he ever president of the Chevra?

R: Fred was a vice-president of the Chevra and he was the adjudant of the cemetery grounds…

M: We’ll go into the cemetery shortly, but first let’s go back to the war years. Did many of the Germans immigrants serve in the war?

R: Oh, absolutely.

M: Do you have any figures or numbers?

R: On our cemetery we have ten members who served in the army….who were in the service. The Weil family who were in the cheese business and I imagine still are the

owners of the American Swiss Cheese Company. Their boys all served in the service. And so was the father of the Weil boys. There were a number of people who were in the service. Those who were in other congregations, Shaare Emeth…all three congregations also served in the army..

M: Did the community talk much about what was happening in Europe? Were they aware of all the different nuances of what was happening?

R: Surprisingly, very little talk about what was happening in Europe. In fact so much so that the people who later on survived iin the 40s and came here didn’t want to talk about it. And they did n’t want to talk to their children about it. There is really a lost generation of children who really knew nothing of what was going on in Germany. I was teaching Sunday School in the early 40s and 50s. The community said “Don’t teach our children about the Holocaust. It’s a bad thing to know about.” But I did teach them on a

clandestine way. And many of those students today acknowledge the fact that I did tell them about the Holocaust.

M: Were you aware of the concentration camps, the horror that happened there?

R: Not till after the war.

M: And then when people discovered they didn’t have family, if their family was killed, how did they cope with that?

R: The community at large really didn’t cope with that. I remember in ‘45 or ’46 when the films were being shown here at the Kiel Auditorium of the actual footage of the opening of the camps and the massive piles of victims. And people looked at that and said it is unbelievable. They didn’t know..

M: You went to that? How many people, how big an audience did they have for that?

R: Oh yes, oh they had huge audiences for that. They had not only film exhibition but they had large photographs, large photographs (5 by7 feet photographs).

M: And after the war did the Germans apply for reparations?

R: That came about ’49, ’50 that reparations were being made. You had to apply for that.

M: There were people within the community that helped other people get their reparations or how did they do that? .

R: There were a few people. There was Dr. Mansbacher’s wife, Ilse Mansbacher. Let’s see—there were a number of people who were helpful in doing it.. I do it now today. Because I think I am the only one left to do it. (?) In terms of reparations there are many people who are getting their pensions from Germany and when they died their wives were eligible. Also then there was another one that came along in the ‘50s: That was child bearing. If a women was below the age of 51 and had a child in Germany, she was

Entitled to education help. It’s not much, but its about $32 a month. But it goes all the way back to 1957.

M: Let’s talk about the cemetery, which was another purpose of the Chevra. Tell us about the cemetery. Who is in charge today?

R: I am the president of the cemetery. The cemetery is the smallest Jewish cemeter—organized cemetery– west of the Mississippi.. It is 88 by 91 feet. It is beautifully kept, surrounded by a large hedge and each grave is attended maticulously with ivy growing

in mounds on top.

M: How many graves did you say there are?

R: There is a total of 278 graves available. We still have about 96 spaces for people. They are all spoken for, but the people are still alive.

M:: You didn’t mention the exact address of the cemetery.

R: It’s 7400 Olive Street Road.

M: Tell me a little about the land and how you got the cemetery property.

R: The cemetery ground initially was purchased in 1932 by Brith Sholom Congregation. They wanted to start a cemetery. In 1932 out there it was pretty much bare. And the cemetery plot had belonged to the Weslyn church group. They had intended it as a cemetery, but never buried anyone on the cemetery. Next to it was a chinese cemetery

shere now Pete’s Supermarket stands. Brith Shalom bought the piece of property, 640 feet by 325 feet. I’m not exactly sure of that. And they bought this property and they wanted to have a cemetery in 1932. They put up a large entranceway to it “Brith Sholom Cemetery” However, nobody wanted to be the first in an overgrown wheatfield. So in 1934-35 they went to New York where a family’s father was dying. They said we will bury their father for nothing if they allow us to bring him to St. Louis It was the

depression years. So they brought the father here and buried him on the plot. In 1936, somewhere between ’36 and ’37, the family came out here to look for the father’s grave and they could not find the grave in the wheat and everything else. So they finally located it and dug him out and took him back to New York. At that time the German Jews began to arrive and showed an interest in starting a cemetery because they wanted to be together. They had lived in Germany together. They came over here and started a new life and wanted a cemetery. So Brith Sholom offcered them the opportunity at 40 cents a grave. And you could take as much room as they wanted and wherever you wanted and we will come out and join you later when we started. For some reason, the German Jews chose to put their graves smack in the middle of this property. And the cemetery is still registered under Brith Sholom still to this day . It is marked on University City plats to this day as the Brith Sholom Cemetery. So the German Jews figured this way that if the other congregations would never come out, they would build a synagogue in the front portion of it facing ours and they would have a cemetery in the back. And as it turns out

of course ….Brith Sholom never came out.

M: What did come on the property?

R: The property intrestingly enough that small plot remained in beautiful condition but the rest of it remained as an overgrown wheatfield. This went on till about 1956 . In 1956 Brith Sholom had the opportunity to sell the property (the whole property) to the Jewish community. They wanted to build the Yalem Branch. However, they wanted the

cemetery removed. This, of course, was a no no, you don’t move a Jewish cemetery. The initial property could have been bought in 1938 for $3500. It was now worth $250,000.

But the J did not want the cemetery. Brith Sholom made various offers to the German Jewish community and said we will do this.. move your graves and give you decent stones, but we had decent stones and we wouldn’t move it. And without going into much detail, they tried to take us to court over that (?). So as a result of that the cemetery is there. The Jewish community did build the Yalem branch in back of it. Later on the community center was sold to the Yeshiva association. And later it was sold to the

Agape.

M: How do you spell Agape?

R: A-g-a-p-e, Agape, which is a Greek word standing for love. It’s interesting that Ohav Sholom means “loving peace” “ohav” meaning love. So the two organizations dovetail very nicely together.

M: And they are cooperative in providing you with water?

R: Prior to the sale to the Agape, there were many city hall meetings which I attended where for seven years the owner of that property, after the school moved out, had tried to do other things with it. For instance, they wanted to build a hamburger joint in front of it. And each time it happened, University City asked “Is this agreable to you” and I said “No way” And then they wanted to build a shopping center, a shopping mall, around it.

I said “No way.” Each time I would be called in And then there was a plan which was the St. Louis Building Association, they wanted 8 low-income housing around the cemetery. I said, “Where would the children play? Not in the cemetery” and they said “No” They always respected us. I give great credit to the Council of University City that they would call me in on this. And so when the Agape came out they did the right thing. They have been very nice neighbors. They allow us to use the water. For some reason,

Our cemetery is landlocked without water. We use their water and made a donation to the Agape.

M: Were there ever any anti-Semetic incidents?

R: Only one anti-Semetic incident happened where a swastika was drawn on the wall facing the cemetery on the inside . Otherwise. Very few people knew the cemetery existed because the high hedge –the hedge is about 15 feet tall—they don’t even realize.

M: The oldest grave was when?

R: 1942. There was a young man named Julius Lorig. Julius had worked for the Defense Department on Goodfellow and there was a small accident in the plant and he was killed

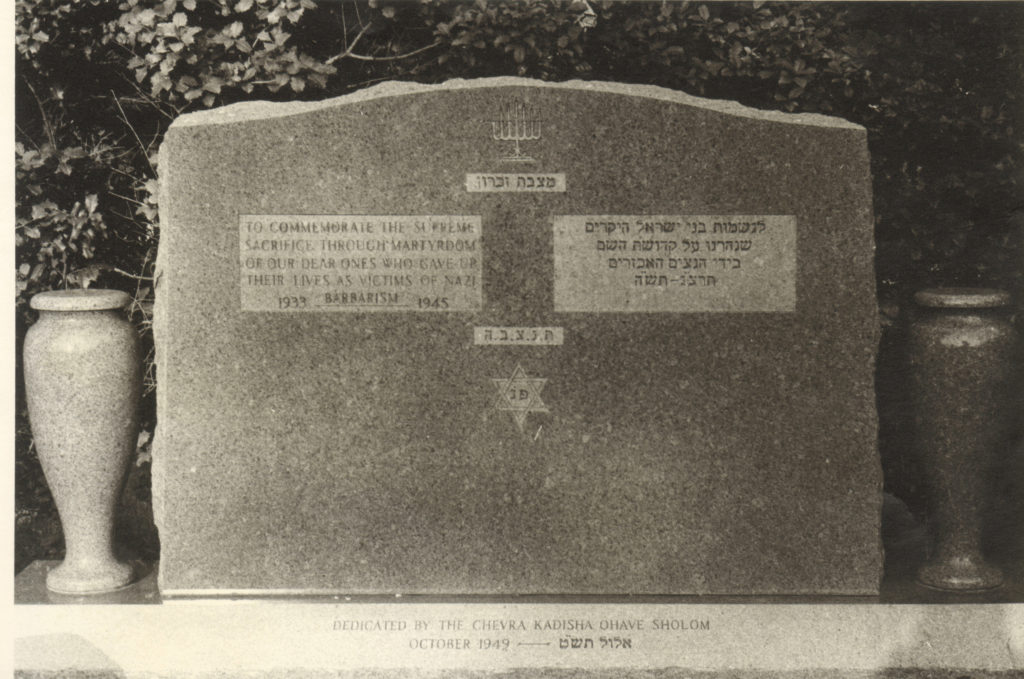

M: There is a memorial stone there?

R: Yes, it is the only cemetery in St. Louis that has a seventeen thousand pound monument, a wide monument, dedicated to the memory of those who lost their lives in the Holocaust.

M: There must have been a big dedication ceremony?

R: There was a dedication. It was dedicated by Rabbi Mazur, Jacob Mazur of Brith Sholom.

M: Does the Chevra get together at the cemetery?

R: Yes they do. The week before the High Holidays, the morning after Slichos, they gather there for a small memorial service for the victims of the Holocaust, for those who have died and in general, it is a practice in Judaism that people go to the cemetery the week before the holidays. So they come there and those people who have no graves to say kaddish can go to this memorial because there is a large grave-like plot in front of it and they can say their kaddish there.

M: Do they light candles?

R: We don’t light candles out there. No

M: What do you see as the future for the Chevra? First of all, let’s go back. They do meet. How often?

R:Once a year we have the Kaffee Klatch, which is really a business meeting with socializing afterwards. At that all we do is give the state of affairs, financial affairs and anything that is pertinent. And that meeting lasts from 20 minutes to a half an hour …and then we have a social hour. Those social hours used to be quite lively with music and entertainment with coffee and cake. And most of all, which is most interesting, not many organizations, they would go to members of the congregation who had businesses,

like Mishow and Kahn and people who worked in other industries because they were German but they had access, and would give gifts. It could have been anything like jewelry that could have been out of style, custom jewelry to nightgowns,what ever, and they would wrap it in funny paper, actual comic paper from the comics. And we would put a number on it and people who would come to the meeting would get a number and afterwards they would be called up. Everyone would get a gift. Even to this very date,

not that you didn’t know what to do with them, some of the beads I don’t think anyone would wear. Anyway, they still insist on having this to this day.

M: What do you see for the future of the Chevra?

R: It’s an interesting question…I’m 75. Some of the young people, a few who are younger than I am, what should we do with the cemetery. Funding—it is well-funded

But who is going to take care of the cemetery is the question. Who is going to take care of it as we would. I was too young when the cemetery was founded in 1937. I think it was a mistake. I think we should have gone to a larger cemetery and taken a area in that cemetery and reserved those spots. This cemetery eventually the funds for the cemetery will be turned over to another cemetery probably the Chevra Kadisha cemetery on Page. I use one of their gardeners to dig our graves and maintain them.

M: Are there any young people who have shown an interest?

R: The youngest people in the Chevra today are in their sixties. I sometimes worry about it but there is nothing I can do.

M: Rudy, I’d like to ask you just a few questions about yourself. I know you have a video interview that we did for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation but just for this tape. When did you come to St. Louis?

R: I came to this country in 1940. We escaped from Germany to Shanghai China. We were lucky that in less than two years we were able to get out of Shanghai and came here.

So my primary education really was here in St. Louis.

M: Where did you go to University?

R: First of all, when we came here we went to Granite City, Illinois because the company that sponsored us –we had done business with them through my father’s

Business.

M: What was your father’s business?

R: Leather degreasing for oils and fats. Some of the by-products were shipped to Granite City.. Actually, the company, Smith-Roland Company had seven plants in the United States. They sponsored us. They took my father to all the plants to choose which plant he would like to work at. After three years we moved to St. Louis in 1943. In Granite City I attended the junior high school and in St. Louis I went to Blewett High School which later on merged with Soldan and became Blewett-Soldan. Then after Blewett, I went to Harris Teachers College for two years and then to Washington U. to finish up my undergraduate degree and then I went into the army, served in Tokyo, Japan and then came back to finish my graduate work as a chemist but I also have a degree in clinical psychology.

M: I think with that, I think we have a very good spokesman and wonderful caregiver for the Chevra. Thank you so much for your interview. Can you think of anything I might have left out? Any items that you might want to talk about before we close this.

R: Not really. I just think that the history of an organization is so important that it should be noted by various organizations and the history of the people coming to

a country…It was so much different when the Russian Jews came over here.in the 50s , 60s and 70s, there was an acceptance of the refugees. But when the German Jews came here, there was no acceptance. The German Jew had to fend for himself.