LEVY: There was, before the Nazis there was a definite relationship between Christians and Jews. Sunday nights the neighbors would sit out – this was a small town – the neighbors would sit outside, take their chairs, and share the news of the week of the town. My parents would always be sitting with them, in the middle of them; we children would play in the street in the meantime.

On winter nights – my mother was an expert knitter. Some neighbors would get stuck with their knitting. They would come over and mother would help them out, what needed to be done to correct whatever they had done. It’s not unusual. A lot of times they would come over just to talk. Maybe somebody had a baby in town, or whatever. Christian people would come over. It was not a strict separation. Like I said, they know – they knew we were Jewish but it didn’t bother them. It didn’t bother them.

PRINCE: Yeah, they were comfortable in your home. Did you go to their homes? Would your mother have gone over there?

LEVY: Once in a great while, not as much, not as much really. Uh, there was a baker across the street. Of course we would go to a business or to the farmer’s to get certain things. Once in a while mother would go of course, but not very much.

PRINCE: But there was that –

LEVY: They came more to our house.

PRINCE: Yes. You were more open and you were hesitant to –

LEVY: Right.

PRINCE: Did your little girlfriends…

LEVY: They came to the house.

PRINCE: They came, and did you ever go to their houses?

LEVY: I went to their houses.

PRINCE: And this was easily – as a child you did –

LEVY: Yeah.

PRINCE: – more easily than the adults.

LEVY: And strangely enough, I usually sought out the people who were kind of poor, kind of the under-dogs. Those children I usually visited more than – and I had other friends too – but somehow I kind of felt sorry for the children who didn’t have a lot of friends or…so I usually was friends with them. And children would come to our house.

PRINCE: The other children, besides the ones that you…?

LEVY: Yeah.

PRINCE: All kinds.

LEVY: Yeah, all kinds. In fact – this was funny – before I started working in Darmstadt to learn sewing, mother thought I have to hold a needle, okay. So there was a seamstress in town and she wanted me to go there to kind of sew little things for myself. And there was one of my former schoolmates was working there too and she asked me to come to her house, and when I came there she proudly showed me the new picture they got of Hitler. She didn’t know that I was not interested in Hitler, (LAUGHTER) didn’t realize that. Now this was in, probably, in ’34. And she was not a dummy. This one was one of the smartest ones in class, but didn’t realize that I really didn’t care about Hitler.

PRINCE: Yeah…you had to act, you had to say the appropriate thing I guess.

LEVY: Well, I, I didn’t say anything. I don’t remember, but…Then this friend who was here a few times, this Christian friend who was my schoolmate in grade school, said that a friend of theirs, they didn’t have a picture of Hitler in the house. So they came and presented them with a picture of Hitler. And the person who brought it, the Nazi who brought it said, “Now where do you want me to put it?” And she said, “I don’t care. You can put it against the wall or hang him up.” So (LAUGHTER) the guy reported her; that was very bad to say something like that, and they did haul her in for a couple of hours because she said, “You can hang him up.” You know, those –

PRINCE: The things like, uh, when you had to write “Sarah” or “Israel” on the letters, was that –

LEVY: That was after me.

PRINCE: Was that after you?

LEVY: That was after Kristallnacht.

PRINCE: Okay, and the star?

LEVY: I didn’t wear it. That was after; that was all after Kristallnacht. And I was not there during Kristallnacht.

PRINCE: How soon do you think things that were happening in large cities got to you all? I mean, I wonder if it was an immediate thing that after Kristallnacht people wore stars and after –

LEVY: We didn’t know that until after, after, you know, after the war. We didn’t…

PRINCE: No, no, I didn’t mean you all, I meant if you lived in a small town when these things were going on, if you had been there, how quickly did it come from big cities into the more rural areas. I wonder, just…as quick as –

LEVY: Only on person to person. I mean, otherwise you didn’t know. It wasn’t in the papers, it wasn’t – it was called gruelmaerchen – you were spreading, uh, lies, anything that if you were truthful about what was going on, it was gruelmaerchen, you know. The Nazis found out that in America they knew some of the stuff that was going on and it was just all lies. It was not true. It just didn’t happen, just the terrible Jews spreading this news.

PRINCE: So I still want to know how you lost your friends and how they treated you when things were –

LEVY: The same way like everybody else.

PRINCE: They just stopped –

LEVY: They wouldn’t talk – they wouldn’t dare talk to me anymore. People who were good friends would pass by me, and maybe on the way by so nobody would see it, they would say hello.

PRINCE: Did your parents ever sit you all down? Or did they need to? Or help you understand why people didn’t like you or didn’t want to be with you anymore?

LEVY: Well I was old enough to know what was going on. I mean, I was in my teens.

PRINCE: Yeah, but, but – you were Jewish and you knew what was happening, but the why of it, the why.

LEVY: Well we all knew that the only reason we were mistreated was because of our religion.

PRINCE: Right, but why did they want to mistreat you?

LEVY: We don’t – nobody knew. Nobody knew why.

PRINCE: Well, I just meant, was there a discussion as far as…

LEVY: No, nobody knew. We just knew, you know, we would talk about different people and we’d say, “Oh, that’s a Nazi, and that’s a Nazi, and this one is not,” discuss different people of town.

PRINCE: Did you cry then when you were young like that, when these things were happening?

LEVY: I cried when, when I was, you know, all of a sudden, wasn’t – was non-existent or worse, sure. And when that glass was on that floor in the store, we all cried like babies.

PRINCE: Did you cry together? You didn’t – you all knew…

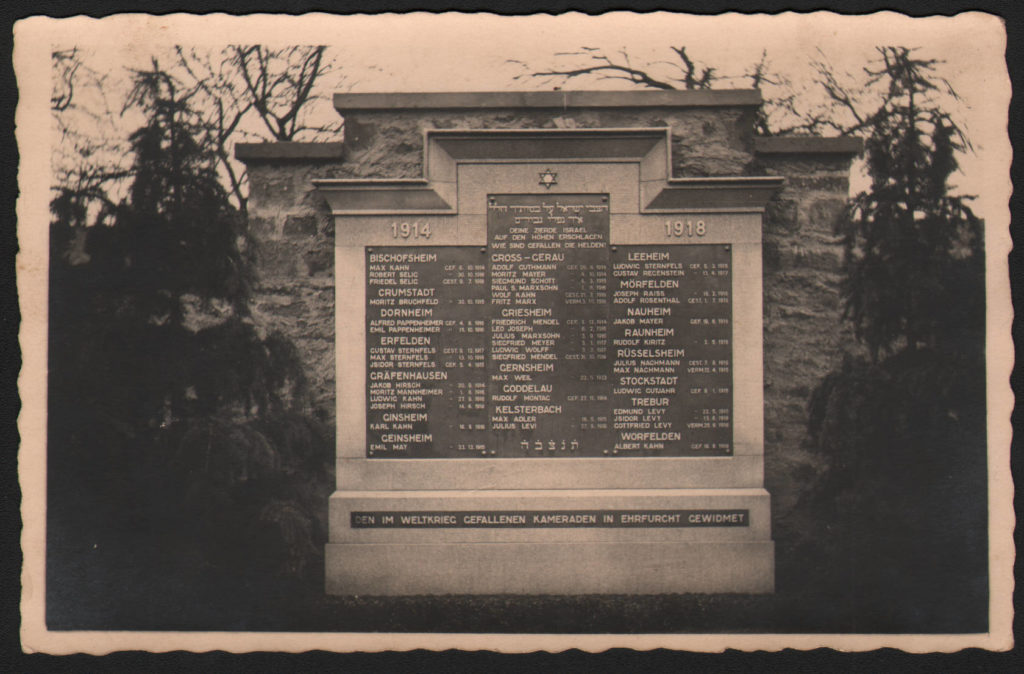

LEVY: Oh yes, because we saw, “My gosh, this is evil worse than we thought.” I remember my father saying, “They’ve already,” you know maybe in ’35, ’36, my father said, “What else can they do to us? They already have taken our dignity. They have taken our business. What else can they do to us, kill us?” Little did he know that was exactly the plan. Who would know? And being in the war and suffering through four years of the war in the front, children would…would say terrible things to him when he came through town on the bike and he couldn’t handle it. He just couldn’t handle it. He would talk back. And then mother was always afraid that he would be picked up and arrested.

PRINCE: Yeah, well and, given your life, trying to be, to be…a soldier in the First War, and then to be treated like – it’s like, it’s like, what’s your life about?

LEVY: It just faded away all of a sudden. (OVERTALK)

PRINCE: Yeah, right. So I would think that a man in that – it has to really be –

LEVY: And you have pride.

PRINCE: Yes, and he can’t protect you.

LEVY: You can’t say anything. You can’t – there’s nobody to go to.

PRINCE: No, no.

LEVY: There’s nobody to go to. You only get more hurt and more insults. It’s – you know – my daughter does not understand it, that I just don’t hate Germany, all of it; that my friend comes here. My daughter can’t stand the fact that I have a German friend.

PRINCE: Is this a friend from (UNCLEAR)

LEVY: Yeah, from grade school, and they were very much anti-Nazis.

PRINCE: And how did you know that?

LEVY: I knew them from child on. I knew –

PRINCE: But did you know that when all this was going on?

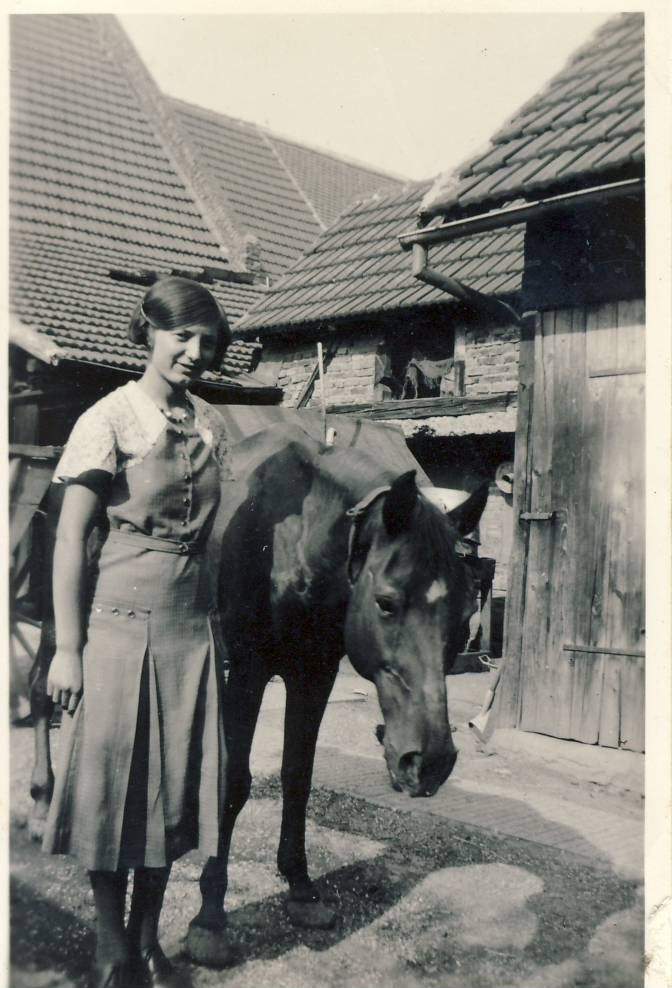

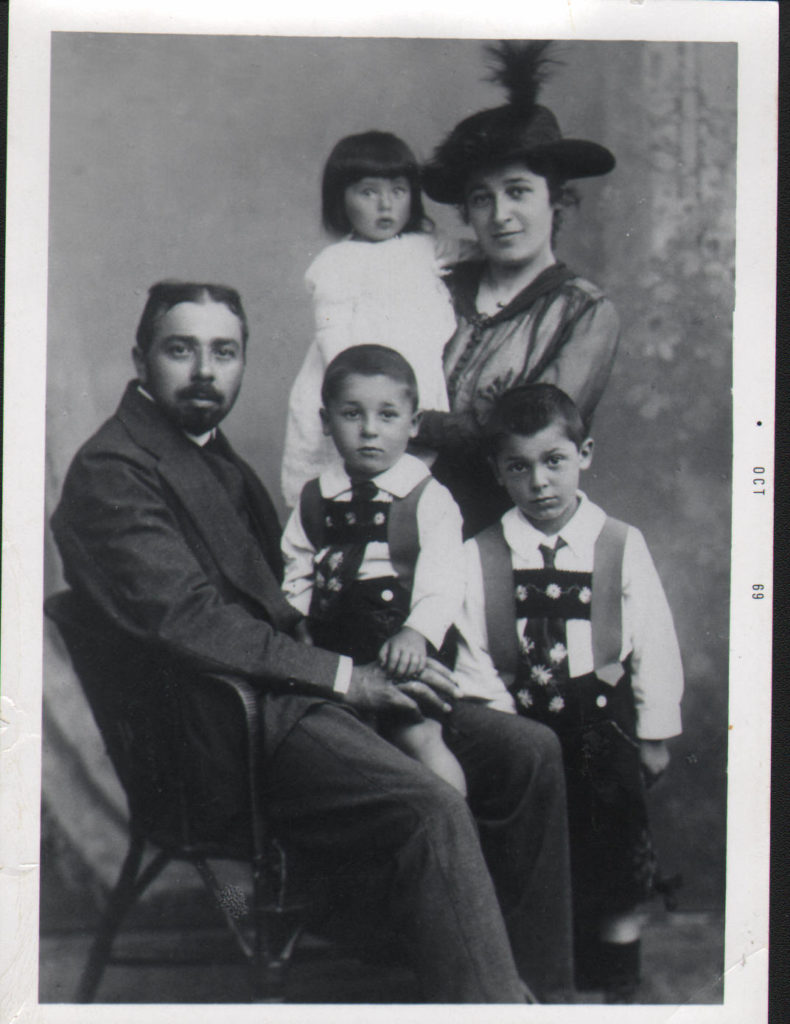

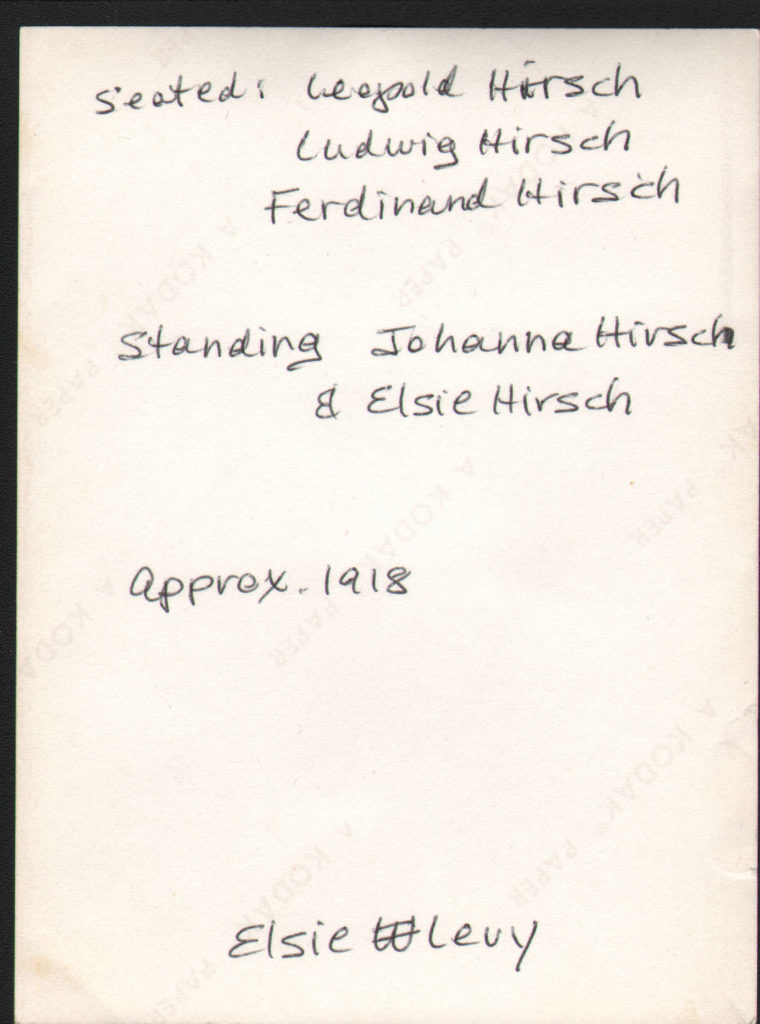

LEVY: Well when all this was going on they were afraid like everybody else. They were fearful. There was something else that happened in my house. I was probably 17, which would make it 1934, okay. There was a sign that said “Leopold Hirsch Hardware Store.” One day the doorbell – the store – somebody comes in the store and mother was busy so I go in to wait on the customer. And in come two SS men. So when I saw them of course I started shaking. They wanted to sell Der Stuermer, that’s Nazi antisemitic paper.

PRINCE: Is this 1934? Did you say?

LEVY: I think ’34. It must have been ’34 or ’35.

PRINCE: SA men maybe, SA – instead of SS.

LEVY: ’34 or ’35, I’m not sure of the year. But I was old enough to wait on customers. So these SS men offered Der Stuermer, they wanted to sell Der Stuermer. So I told them we’re Jewish, we’re not interested in Der Stuermer. But I had a long conversation with them. I was pretty quick with the answers at the time, and they left.

After they left there was something on the counter. This was called a totschlaeger. It was a metal, metal handle, and out of it came a metal spring. Totschlaeger is a killer. It was left on the counter. Now, what to do with this thing? Is this something they planted there for the Jews so they can say the Jews had this weapon? Or will they come back to pick it up? We didn’t know what to do; we were so frightened. We didn’t know what to do with it. So after a week or two we buried it in the backyard. So we felt sure they would not come back for it. But all these little scares, these ways of living – left this darn thing on the counter. I can still see it. I can still see it. It was like a handle – like this. And out of it came a metal spring, and that’s what they used to – it was a weapon.

PRINCE: It was a weapon.

LEVY: It was a weapon.

PRINCE: And you couldn’t, you know, go after them and say, “Here, you left this,” because then…

LEVY: Well, they were gone, you know, they were gone. (OVERTALK) Just little incidents that happened, (LAUGHTER) sometimes you wonder how you lived through it all. And, and of course it got so much worse after I left.

PRINCE: Well I think that’s – it’s very interesting about your daughter –

LEVY: She can’t accept it.

PRINCE: No, that, that the two of you have this parental dilemma.

LEVY: When I say, “You don’t understand.” She says, “No mom, you don’t understand.” I said, “I’ve lived it.” And she just can’t accept – she won’t even let me explain because it’s so much easier, like people who hate Blacks. It’s so much easier to take people in a group.

PRINCE: You have, you have chosen that this is the way you can live with your life, is to live this – feel this way.

LEVY: I know that there were good people. Next door to us, the people also sold – is it still on?

PRINCE: No, we’re fine. I just have to keep looking at the tape to be sure that it hasn’t stopped and you’re not…

LEVY: Okay. Next door to us, we were not the best of friends because they were kind of competition. They also sold stoves and sewing machines. During the Nazi time, people would – and our window was into their yard, okay. People would come in their yard, they would let them come in their yard, knock on our window, and tell us they want nails or whatever they need. And we’d sell ’em through the window. They weren’t Nazis. Even though, like I say, we were not the best of friends because of the competition, neighbors were not – a lot of them were not for this. First of all, there was the Depression in Germany. People were out of work for years. Hitler came and promised them everything – promised them work – and they did get work because he prepared for the war. He did all this work, that he could really get people working. But little did they know what it was all about.

PRINCE: Uh, do you find that there are other people, like yourself, who share your feelings about the Germans?

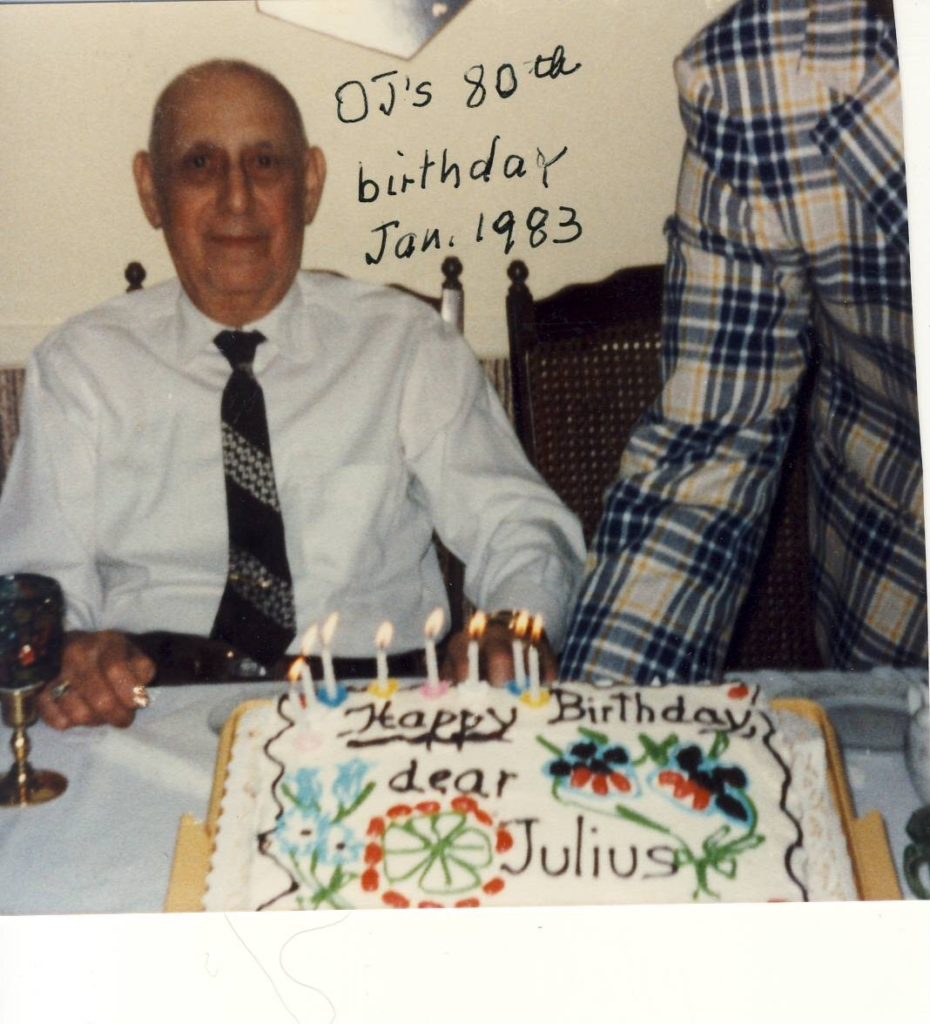

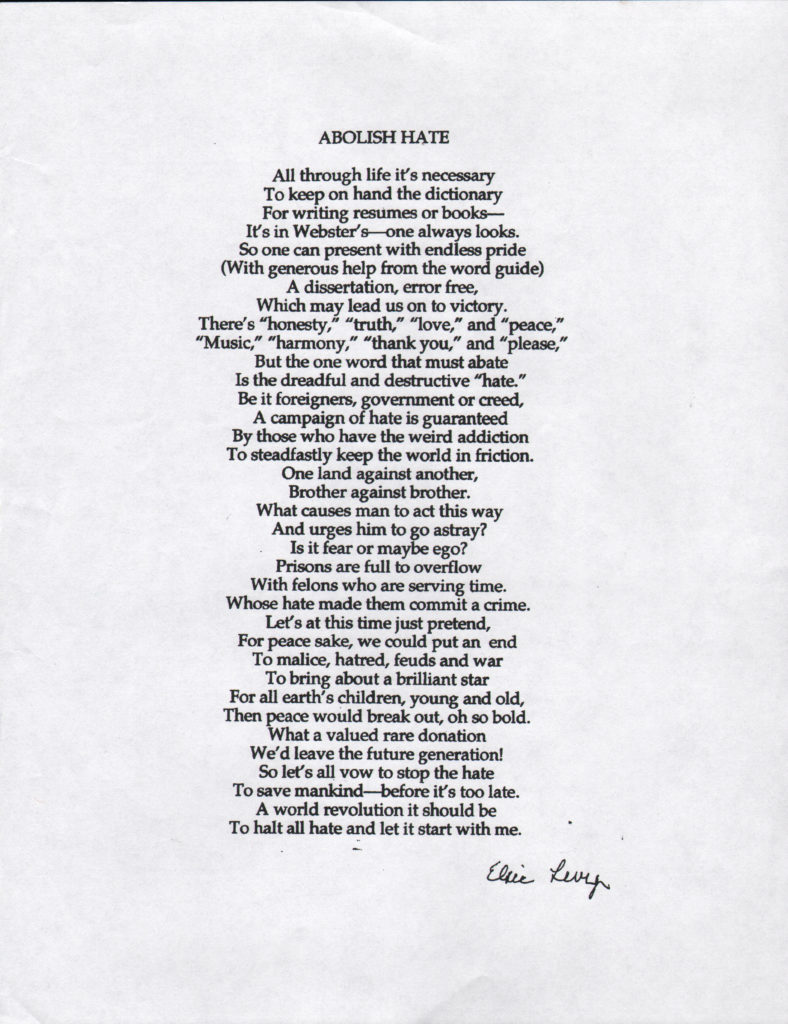

LEVY: There are, but I think not a lot, because for most people it is much easier to just hate everybody. And that’s when I wrote a poem about this because that makes me crazy. It’s – I don’t know if you want to (SHOWS POEM)

PRINCE: All right, well maybe we’ll have you read this at some point. Uh, let’s see, I had another…(TAPE STOPS)

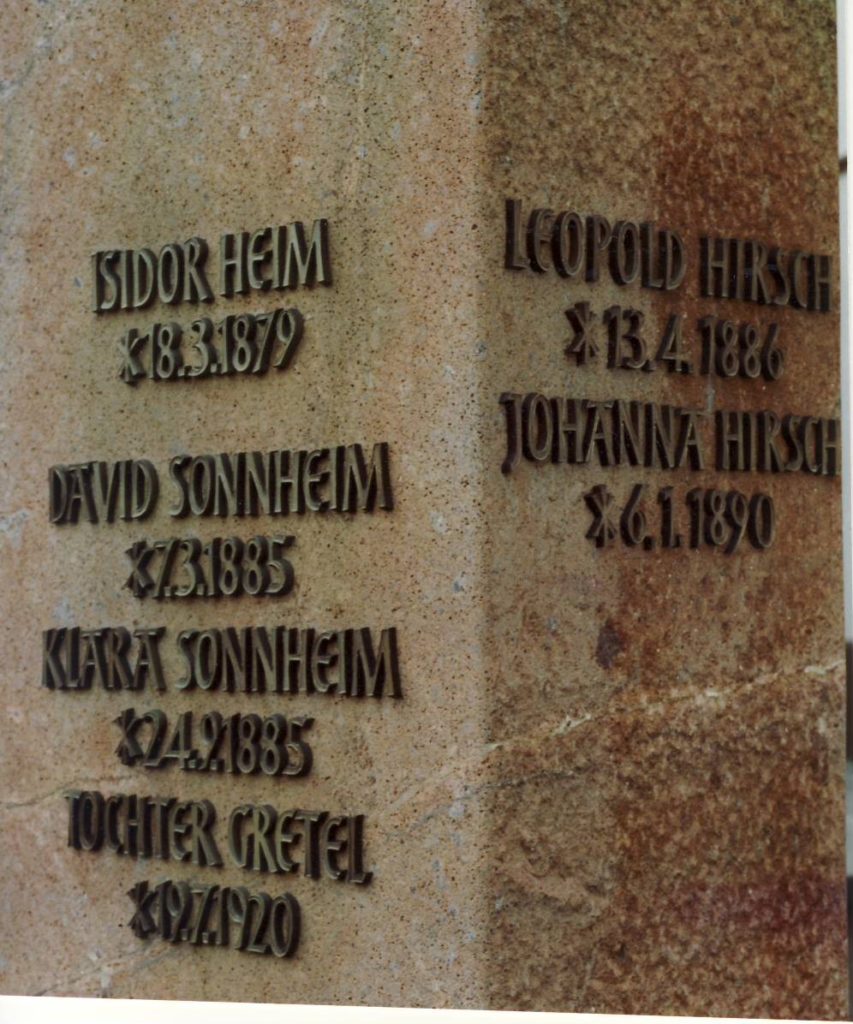

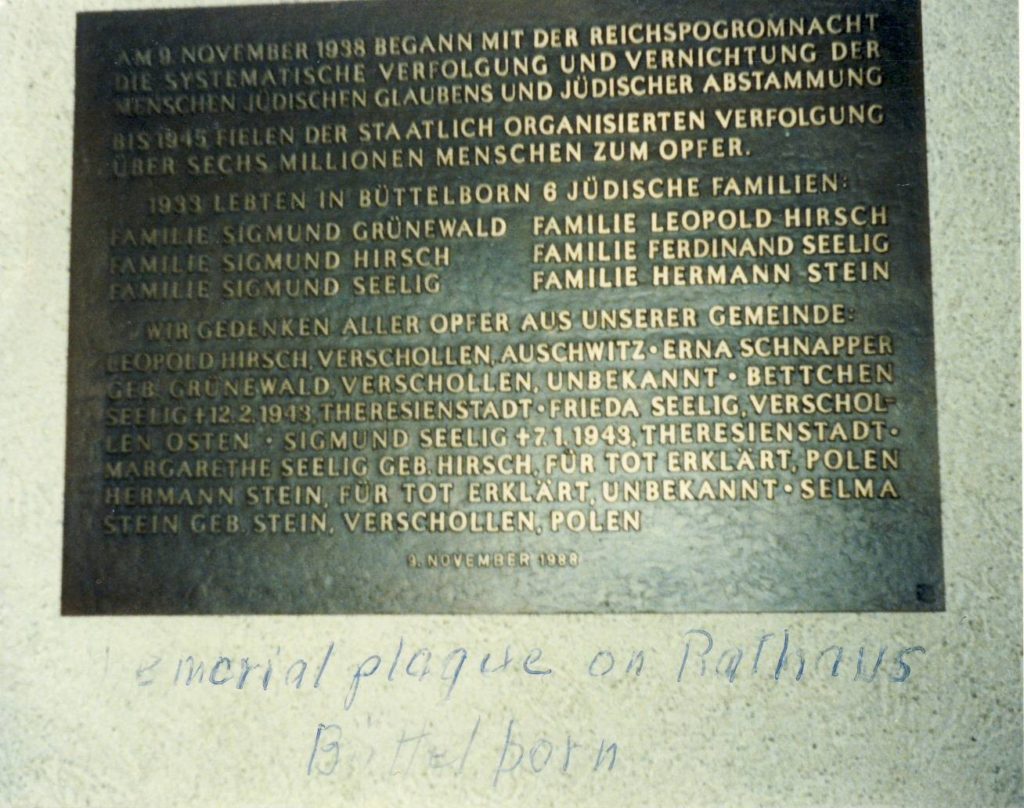

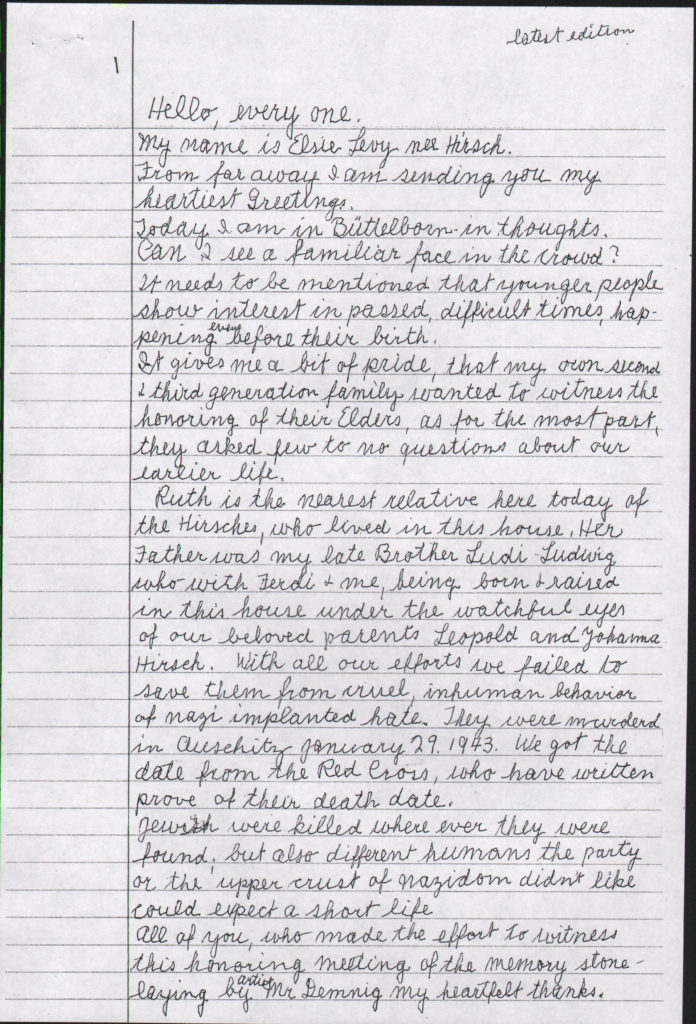

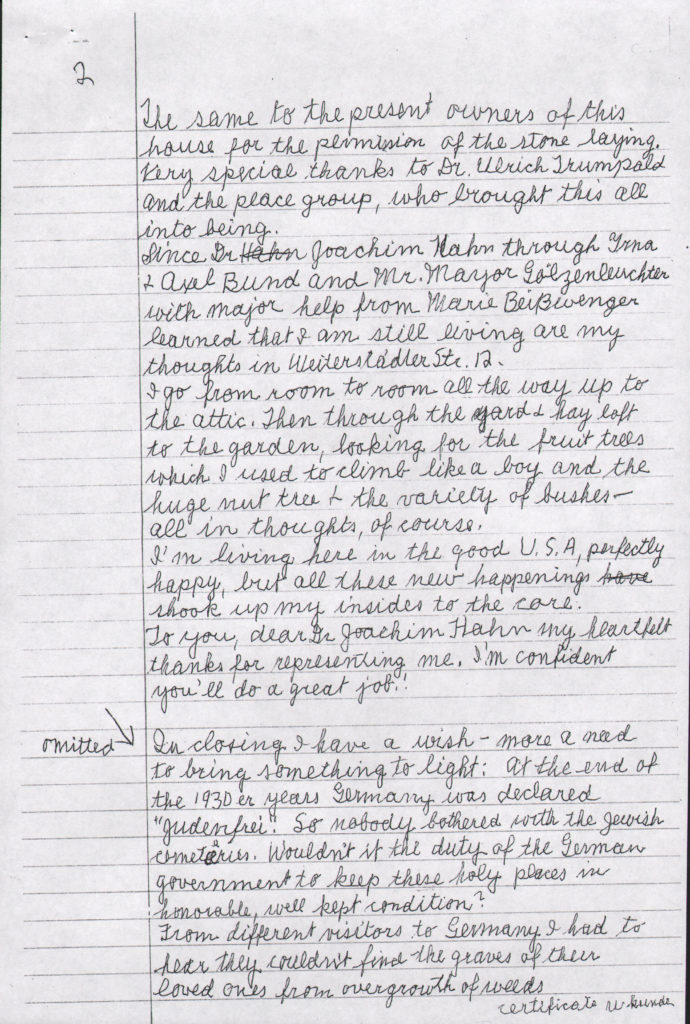

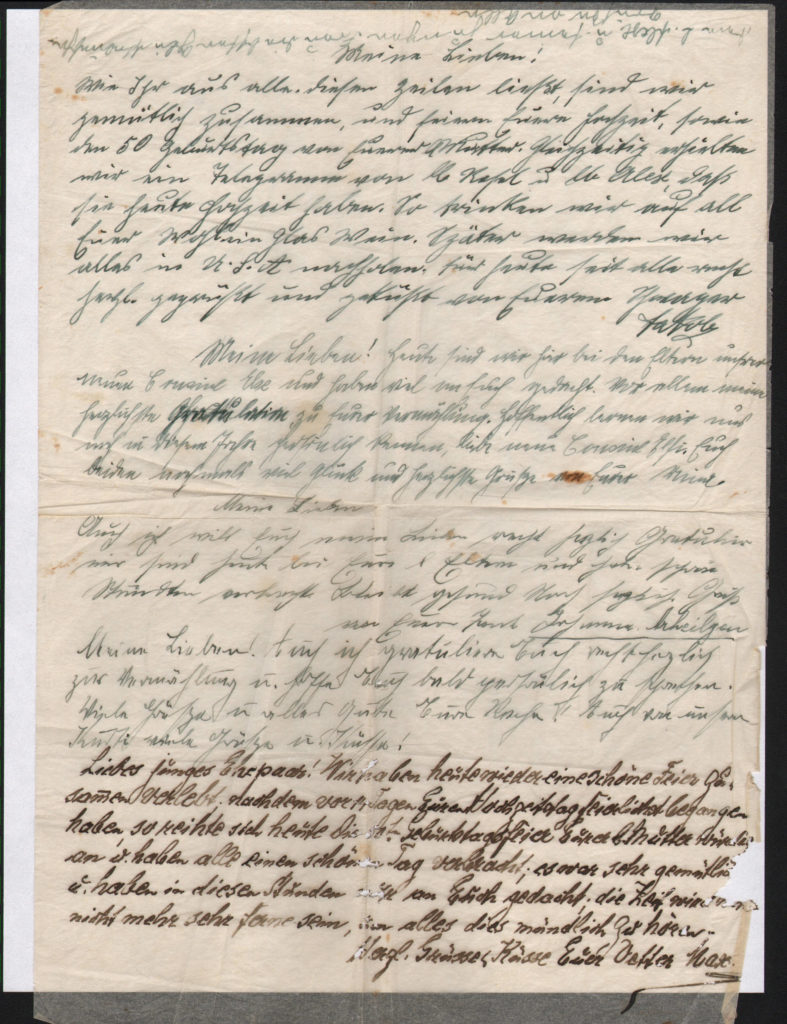

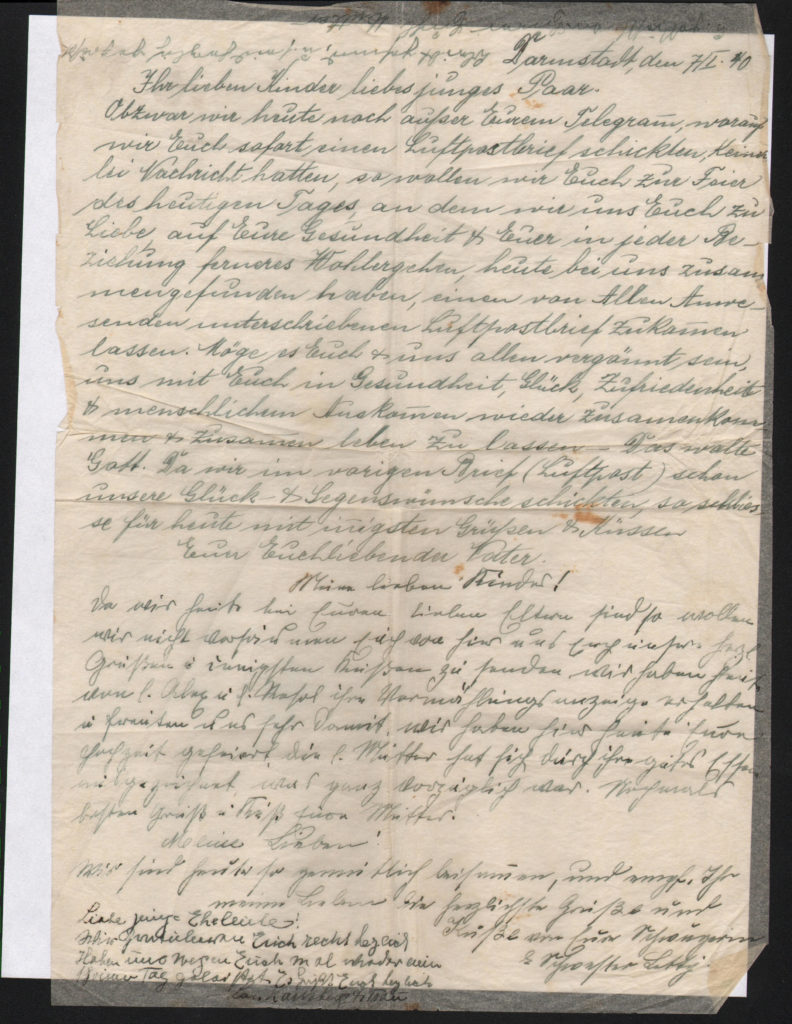

LEVY: In 1988 my husband and I were invited to go back to Germany for the 50th memorial of the Kristallnacht. And I always – I always swore high and low, “I’ll never go back to Germany,” because I was there once in ’64 and I was very uncomfortable. But my husband wanted to go and he wouldn’t go by himself so okay, reluctantly I – we went – I went. We got such a reception. I mean, we felt like some personality; they treated us so well.

PRINCE: Were you in a group?

LEVY: Just my husband and I. They had invited a bunch of people but because it was like 10 days before, two weeks before, that they, you know, that they invited us, there was so little time between; nobody else came. We were the only ones who came.

PRINCE: And this was Darmstadt? Or…

LEVY: This was in Grossguera, which is the town seat of Buettelborn, okay, _______. And they treated us beautifully. There was a welcoming evening in Buettelborn in the town hall and there were a lot of Christians. And I was more than glad there was a group of maybe 45 – 40 people, 40, 45 people there to greet us and to ask questions. Mostly younger people and they didn’t know – they knew something happened to the Jews, but they didn’t know exactly what it was. And that’s when I thought, “Good, I’m glad I came,” and I could tell them what happened to us. And they would ask questions like, “How could you live like that? How could you live like that?” Well, we lived like that because we had to. Good people would come and help us out, through the backyard, whatever they could for us. So, uh – I mean, it was cost free. They paid for everything, bouquets of flowers, and money, and what all.

Then the hometown of my mother’s invited us to be sure and come. Well, we were only there 10 days; it was so short, okay, so we went there. And again there was, in a private home, a man who is into the Jewish history invited us, invited some more people from the town, and one lady says, “Here is something that belongs to you.” And she puts out a sugar tong that my mother had given her because she brought food to them to Darmstadt.

PRINCE: Wow. A sugar what – a sugar…?

LEVY: Her mother had sent her to my parents.

PRINCE: Yes, but what did your mother give her?

LEVY: A sugar tong, you know.

PRINCE: Oh, a sugar tong.

LEVY: A sugar tong – tong?

PRINCE: Tong, yes, I’m sorry.

LEVY: And I – I have it here.

PRINCE: Oh my.

LEVY: So that was of course very touching. And while we were there, there was also in Darmstadt, they had built a new synagogue. And the, uh, what is he…more than the mayor – anyway, a bigshot from the area.

PRINCE: Governor?

LEVY: Whatever, sent us a chauffeur with a car and drove us to Darmstadt for the dedication of the new synagogue. And of course there were no more tickets for in the synagogue but they had a separate room where they showed it on the screen and he got us in there. And there were a lot of people from different countries they had invited for this day. That was another touching, very touching, occasion. But I was really glad then that we went because these young people did – and we made a lot of friendships then. Different people who we met there became friends and have visited us here too. And then I thought, “Gee, Germany has really changed.” And then after we were back awhile I thought, “What are you talking about? Only the good people came to see us.”

PRINCE: (LAUGHTER)

LEVY: The bad people are still there, you know. They didn’t want to see us.

PRINCE: Right…how did you get – and then we’ll wind it up I guess, unless you have something else. How did you get involved with your schoolmate again?

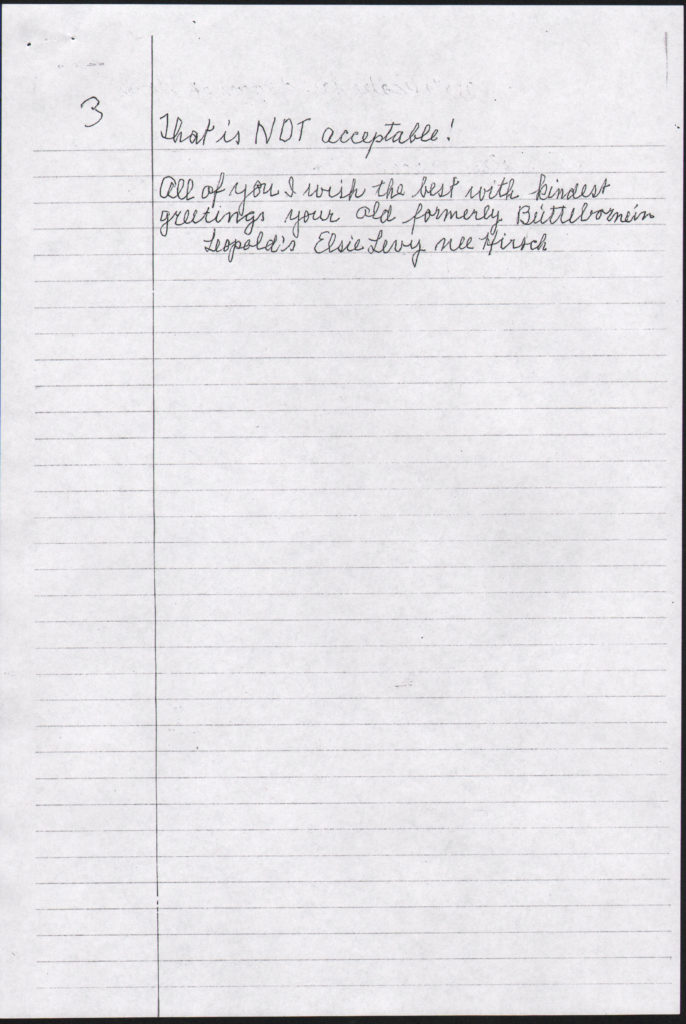

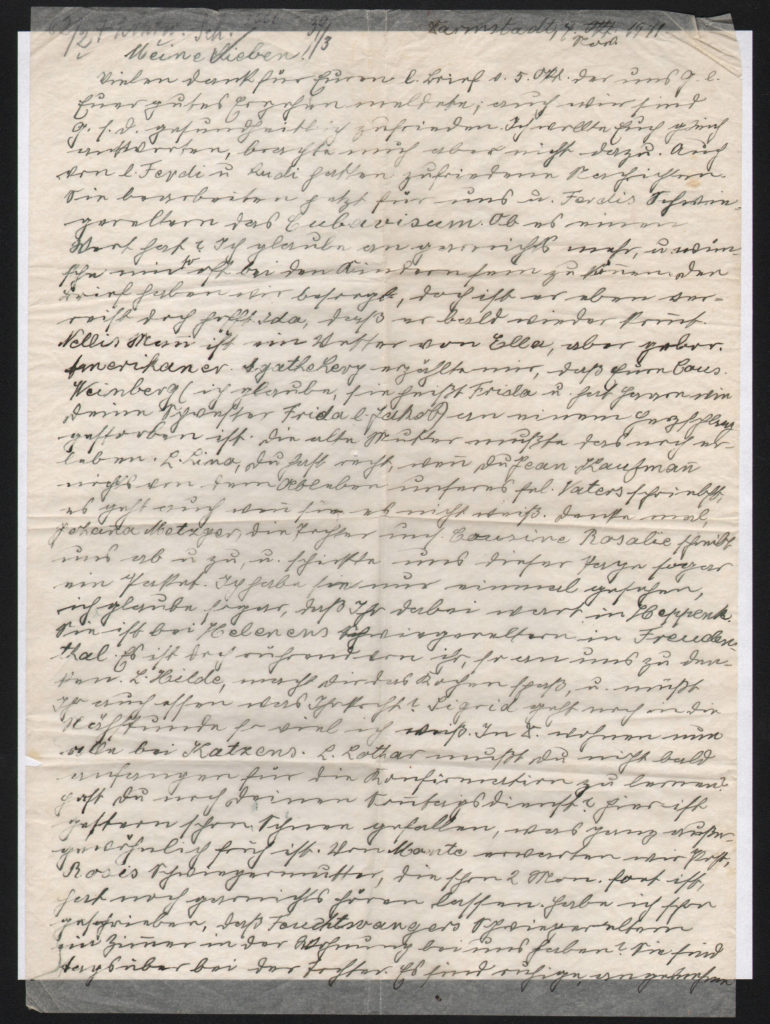

LEVY: Well, after the war she wrote. She wrote me a letter.

PRINCE: She knew where you were?

LEVY: Uh, how did she find my address…oh. You know, I don’t remember. I must have been in touch with her before the war because during the war nobody could write. She wrote to me – oh no, I know why. Another schoolmate of hers and mine who was –

PRINCE: Was this public or private school? Which school was it?

LEVY: No, this was the public school.

PRINCE: The public school.

LEVY: Public school. And he was thrown into jail for distributing anti-Nazi papers during the Nazi time and he was caught at it and he was thrown into jail. And I knew that, and I sent him a package after the war.

PRINCE: Oh.

LEVY: And he got so excited and he was a friend with this friend, Marie, and he was here once.

PRINCE: What was her name?

LEVY: Marie Beissweinger, Marie.

PRINCE: Okay.

LEVY: Okay. In fact, she gave 30 dollars to the Holocaust Museum when she was here last time. But that’s how he got my address, and I don’t remember how I got his. But when he was here he was still excited about the package because it happened to come on his birthday, which I didn’t know it was his birthday. And he said the post office called him at the time and said, “Here is a package from America.” And he said, “I don’t have anybody in America.” Well, it was a package from me because I always felt people who fought that kind of stuff deserved to be rewarded.

PRINCE: Okay. Would you like to read your poem?

LEVY: Okay. (PAUSE WHILE GETTING PAPER READY)

Abolish Hate

All through life it’s necessary,

to keep on hand the dictionary.

For writing resumes, or books,

it’s in Webster’s one always looks.

So one can present with endless pride,

with generous help from the word guide

A dissertation error-free,

which may lead us on to victory.

There’s honesty, truth, love, and peace,

Music, harmony, thank you, and please.

But the one word that must abate

is the dreadful and destructive hate.

Be it foreigners, government, or creed,

a campaign of hate is guaranteed

by those who have a weird addiction

to steadfastly keep the world in friction.

One land against another,

Brother against brother.

What causes man to act this way

And urges him to go astray?

Is it fear or maybe ego?

Prisons are full to overflow, with felons who are serving time

whose hate made them commit a crime.

Let’s at this time just pretend for peace’s sake,

We could put an end to malice, hatred, feuds, and war,

To bring about a brilliant star.

For all earth’s children young and old,

in peace would break out oh so bold.

What a valued, rare donation,

we’d leave the future generation.

So let’s all vow to stop the hate,

to save mankind before it’s too late.

The world revolution it should be,

to halt all hate and let it start with me.

PRINCE: You’re very creative.

LEVY: It’s one thing – I just felt like I had to do something. So that’s the story.

PRINCE: You’ve been very kind today, and very articulate, and very giving, and I appreciate it.

LEVY: And thank you for doing this.

PRINCE: No, thank you. And if you think of something else that you think…I can always come back. I appreciate it.

(End of Interview)

PRINCE: Today is September 4, 2002, and I am back with Elsie Levy for just a few more moments.

Elsie, let’s begin with when you left, were able to leave Germany.

LEVY: Okay. My two brothers came here first. And they sent – I mean, being here shortly they didn’t have a way to send a large affidavit, meaning the, uh, what you’d have to get before you get the visa to enter the United States. So, when the affidavit came, it was not large enough for my parents and me to leave together. So it was decided I would –

PRINCE: Large means the amount of money?

LEVY: The amount of money, yes. And it was decided that I, being young, the parents said, “You go first and we come later.” Well, as it turned out, that was not to be. The parents never came because my mother eventually got her visa, but father did not because he had illness before. So he did not get his visa. So mother, of course, would not leave without him.

Uh, when my father had spent four years in the First World War and came back walking with the cane, and he got his little pension. And then Hitler came in power; that was cut off. He didn’t get the pension anymore. So I came here. My father used to say, “What else can they do to us? They have already taken our dignity. They have taken our business.” By that time there was no more business. “What else can they do to us, kill us?” Little did he know that was exactly what they were planning. Who would believe a cultural country, like Germany was supposed to be, they would have plans like that? Well, they did it very efficiently like they do everything else, as we know – their murder factory. That’s plural – murder factories.

Well, I left Germany in 1938, August 1938. My parents brought me to this train and of course for me, I was 21 years old. It was, you know, it was exciting coming to America. My parents would come right away so that was no big deal leaving. So I went first to Holland, then to England. Then England in Southampton I got on the boat, the Aquitania. Do not write the style line, which is no longer in existence. And then I came here. One of my brothers picked me up here. On the boat, well, it was not – there was a lot to do on the boat, that young people did.

PRINCE: Were there people like you? Was there talk of leaving Germany and why you were leaving Germany?

LEVY: Yes, there were a lot of people who were fleeing from Germany to come to the United States, the lucky ones who could get out. And, uh, so there was a group of us. And we had fun on the – on the boat.

PRINCE: So the atmosphere was one of…what?

LEVY: Well, of course everybody still had some people left behind, but most of the people thought they would come.

PRINCE: Yeah.

LEVY: Nobody realized that they would never see them again, like the kindertransports, same thing. So, when I got here, my brother was here to pick me up in –

PRINCE: Where’d you land?

LEVY: Excuse me?

PRINCE: Where did the ship come in?

LEVY: I was trying – Hoboken. Hoboken, New Jersey.

PRINCE: Oh, Hoboken, New Jersey.

LEVY: Yeah. And so I – my younger brother who was working nights, he took me around for a job. I had to have a job because I was – I came with 20 dollars to my name. That was all I was allowed to take out, and some linens and stuff at that time still let you take out, some dishes that were my parents’ that were supposed to be for my parents when they came.

By the way, when I, okay, before we left Germany there was an organization that was called Zoll Fahnduing. That meant that the customs would come to your house and check everything that you were taking. Anything you took that was new, you had to pay them again. That was, uh, custom duty to them, the same amount that, you had to show –