E. RINGERMACHER: Plain, plain old me.

CARGAS: You have the education of experience, though.

E. RINGERMACHER: That’s right, experience, yeah.

CARGAS: So may I begin by asking you what has it meant to you in your life to be a survivor?

E. RINGERMACHER: What it meant, I really cannot explain. It just for the Jewish people a survivor to tell the story of what happened, how it happened, and what happened in the time, in my generation.

CARGAS: So you tell the story—

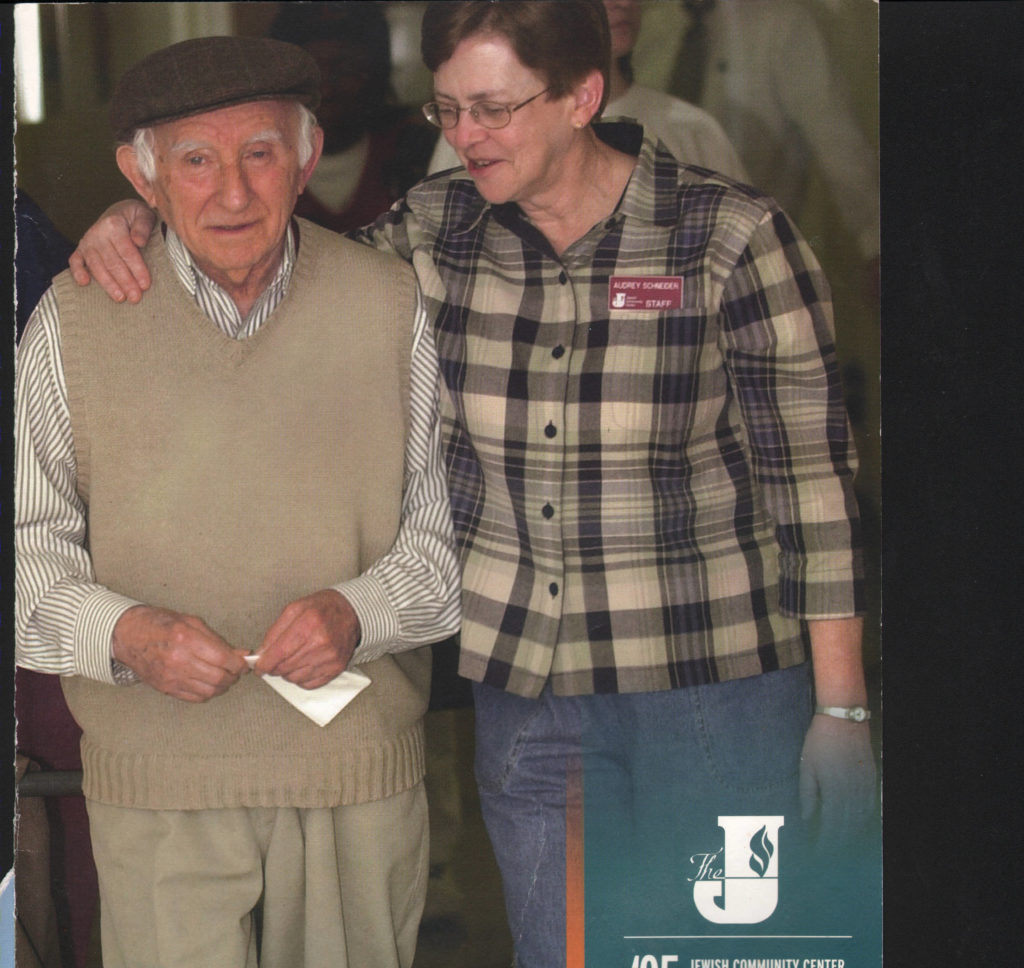

E. RINGERMACHER: I do tell my kids, my family and wherever I can. We just had in the JCCA—what was it—the Holocaust Memorial.

CARGAS: With Yaffa Eliach.

E. RINGERMACHER: With Yaffa Eliach. She was there. And my husband was the one what he lighted a candle.

CARGAS: Yes, yes, the six candles. For the six million–

E. RINGERMACHER: He lighted the candle for Buchenwald.

CARGAS: I see, yes. Most of the people who lit candles were from Poland.

E. RINGERMACHER: That’s right.

CARGAS: Yes, yes, I noticed that. And you see, that’s really why I am interested in the Holocaust. It is my people who did this. And I want to know, if I can, what that means to us also.

E. RINGERMACHER: That’s right. They was in cooperation with the German people a lot.

M. RINGERMACHER: They helped. They didn’t discourage. They encouraged it.

CARGAS: Mr. Ringermacher, then you also are a survivor.

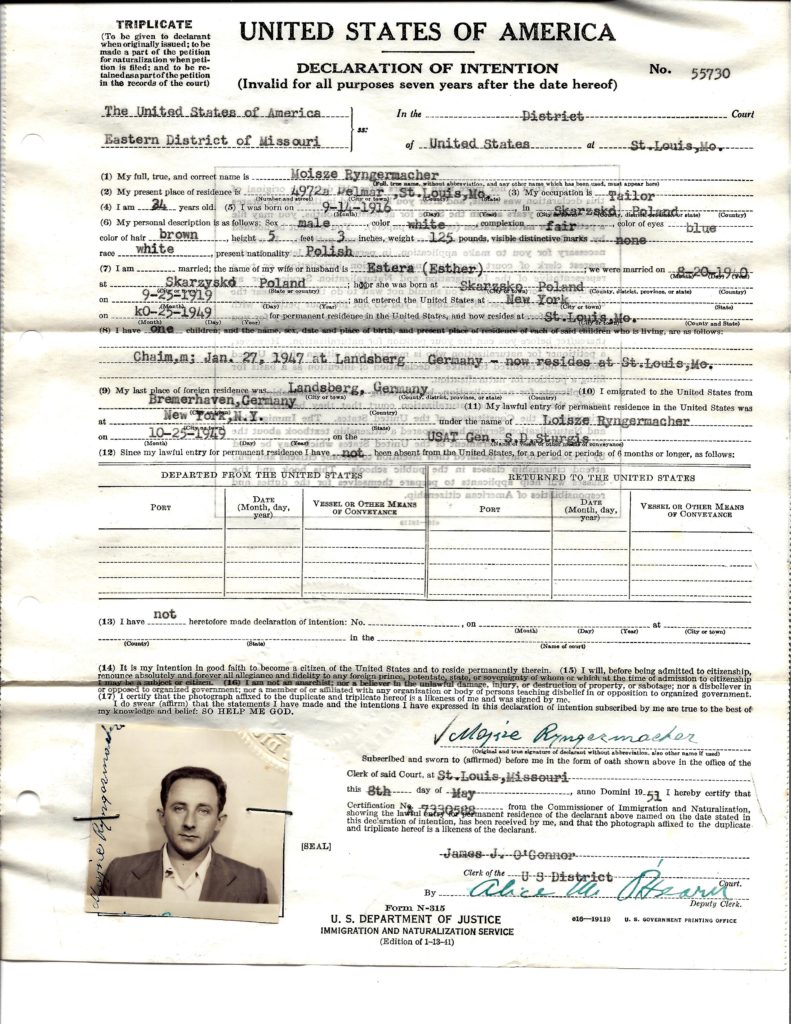

M. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, that’s right.

CARGAS: What has it meant to you to be a survivor?

M. RINGERMACHER: Well, it’s the same thing here. I would like—we are happy and glad that we survived but, in the opposite, we are very—

E. RINGERMACHER: Very sad.

M. RINGERMACHER: Very sad what’s happened to our generation at that time, and to our families and to all of them, what they got lost during that Holocaust thing in the late ‘30s and in the ‘40s.

CARGAS: Do you have fears that this could happen again?

E. RINGERMACHER: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. Yeah, constantly fears that especially in the European nations. About this country, I got doubts because I believe in this country better than in all the European countries. But still, it involves a lot of work and a lot from all kind people.

CARGAS: Do you feel that other people, other than Jews, are working?

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, of course.

M. RINGERMACHER: And another thing, United States is not—it is a state of nations. It’s not one nation. It’s a nation of nations from everywhere. So it’s a different thing here from the European countries. It’s more unlikely it shall happen here because of this.

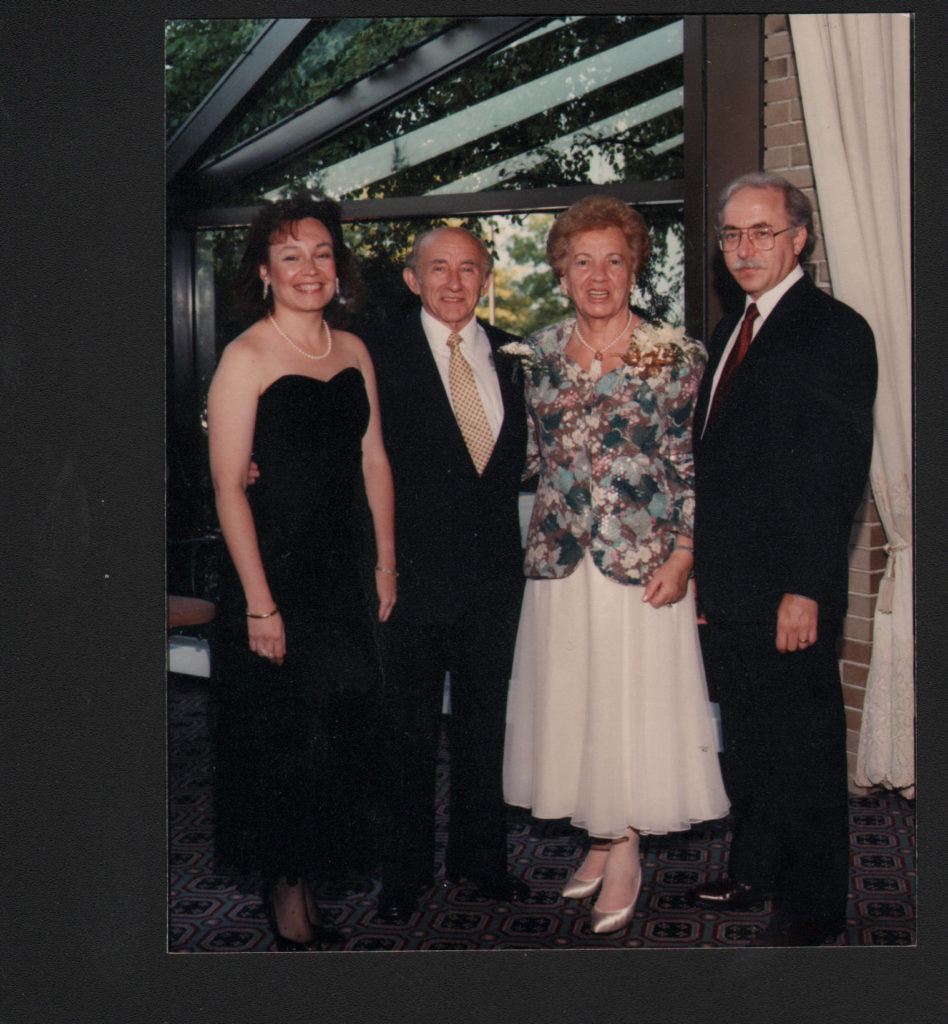

CARGAS: And do you have family, children, and grandchildren, and so on?

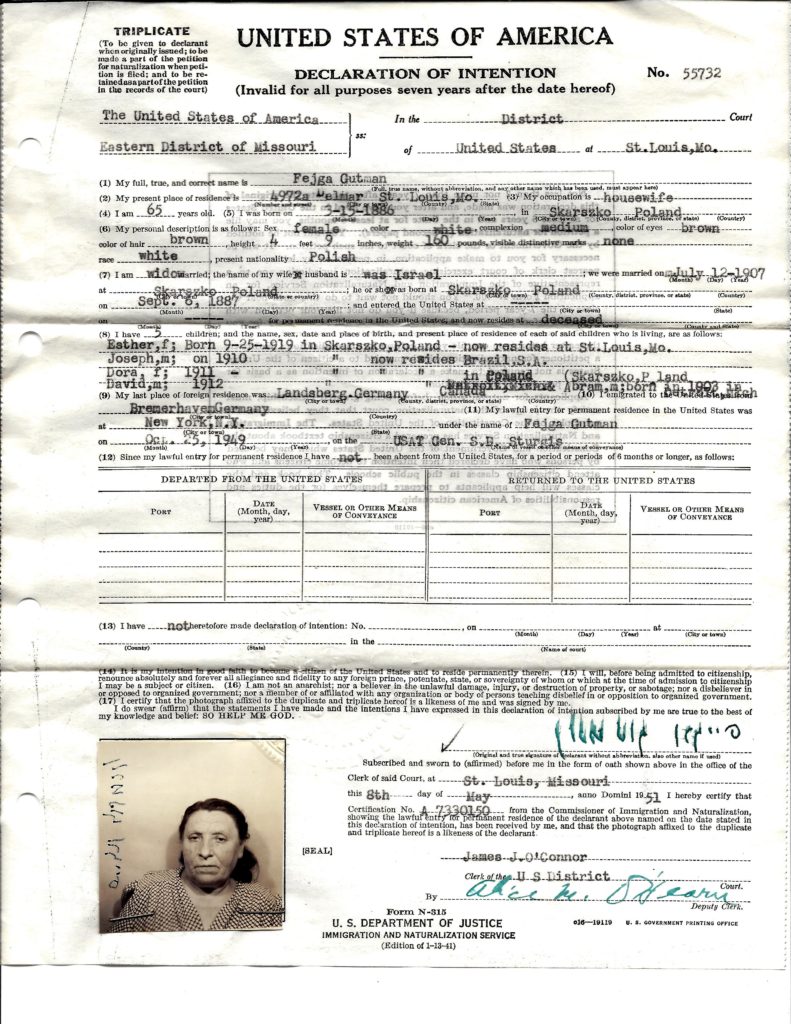

E. RINGERMACHER: I have a son and daughter and a grandchild. I have a sister and brother.

CARGAS: And they were all born here?

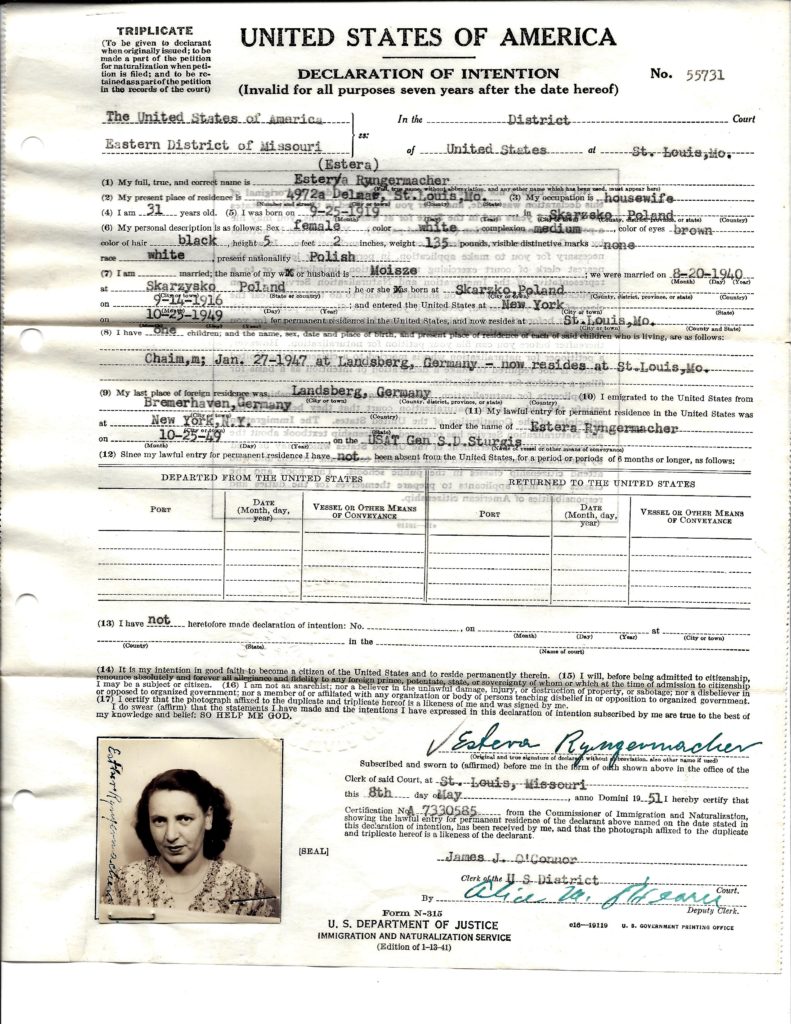

E. RINGERMACHER: No, no. They all born in Poland. No, my children—my son was born in Germany, and my daughter was born here.

CARGAS: But they all here now?

E. RINGERMACHER: Now they are all in St. Louis.

CARGAS: They are all in St. Louis. Good for you.

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah.

CARGAS: Have you felt, either of you, that there is some reason why YOU have survived?

E. RINGERMACHER: Well, it’s no reason that I have survived. That’s not that I was better than anybody else. It was some better people than me what went to the ovens, more religious and more better people than me, I imagine.

M. RINGERMACHER: It’s nothing against other people, but brains.

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, but I don’t mean that because—it was just pure luck.

M. RINGERMACHER: It’s luck and destiny.

E. RINGERMACHER: I don’t know. Destiny, I don’t know.

CARGAS: What do you mean by destiny?

M. RINGERMACHER: I compare this with luck, and that’s the way it’s supposed to happen and God decides. It’s from upstairs. It’s a God’s thing, that’s all.

E. RINGERMACHER: I don’t even know if it’s God’s thing. If that had been choosen, he would choose better people than me, really. But I just think it’s plain luck. It just happened like this, and it came out like this, just for no reason, for no reason. Just in time when we had to be killed, then it was the end of it, and we survived.

CARGAS: The end of the war?

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, the end of the war, and we survived.

CARGAS: And that’s how you survived, not through escape or—

E. RINGERMACHER: No, no, no, not through escape, nothing.

CARGAS: Some people were thought dead, and they were still alive?

E. RINGERMACHER: No, not through escape, nothing. We just—by the end, when the Russians from one side and the Americans from the other side, they pushed in, you know, to Germany, and they didn’t have where to take us. All the places where there used to be the big concentration camp was already taken, was liberated, and I wasn’t in a bad camp. I was in a arbeitskamp.

CARGAS: Arbeits?

E. RINGERMACHER: Arbeitskamp. Do you know what this means?

CARGAS: No.

E. RINGERMACHER: A working camp.

CARGAS: A working camp.

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, that’s German, arbeitskamp.

CARGAS: All right. Did it have a name, a special name?

E. RINGERMACHER: It was Leipzig in Germany. Leipzig, Lichtenfeld.

CARGAS: Lichtenfeld?

E. RINGERMACHER: Lichtenfeld, yeah. It was a –it’s outside of Leipzig—ammunitions, ammunition fabric.

M. RINGERMACHER: Ammunition factory.

E. RINGERMACHER: factory, yeah. So by the end of the war when America went in on one side and then the Russians came from the other side, they didn’t have where to take us. So they was packing us on the Elbe. Did you heard of the Elbe?

CARGAS: Yes.

E. RINGERMACHER: They was packing us on the Elbe by ship. So we thought any minute, they gonna sink us (LAUGHING), but they was afraid already—the Russian was on the side of the shore.

M. RINGERMACHER: They were afraid for themselves.

CARGAS: Oh, the Germans put you on the ship.

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah. They took us out from camp. They want us to take to another camp, to another camp on the other side on the Elbe River, but it was too late because the planes and the soldiers already was surrounding, and the bombarding and everything, and they couldn’t do nothing with us. So they left us on the side by the river, and THEY escaped. And they left us just on the side by the river.

CARGAS: And were you at the same camp, Mr. Ringermacher?

M. RINGERMACHER: No, I was in Buchenwald, and then they sent us to a place by the name Schlieben.

CARGAS: Schlieben?

M. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, and this was a camp, the same thing. This was also a concentration camp, but it was a working camp. It was a place where they worked the Panzerpalz, they called them, “Panzerpalx”, [which means] against the tanks.

CARGAS: Yes, against the tanks.

M. RINGERMACHER: Yeah. And from over there they took us to Theresienstadt.

CARGAS: Oh, yes.

M. RINGERMACHER: And from over there, this was in—we were over there about six weeks. And then we got liberated a day later. It was on the 9th of May. We took them out and more because they got surrounded, the SS got surrounded, but then they hide themselves in the mountains around Theresienstadt, and they couldn’t get them. It took them a day more to get rid of them, and then we got liberated.

CARGAS: May I ask you where are you from exactly in Poland?

E. RINGERMACHER: Skarzysko. Skarzysko, Poland. Let’s say how you spell it.

CARGAS: I’ll find it, I’ll find it.

E. RINGERMACHER: No, I can spell it for you. S-K-A-R-Z-Y-S-K-O, Kamiena. This is on the river, Kamiena.

M. RINGERMACHER: This is 150 kilometers from Warsaw.

CARGAS: Okay. Good.

M. RINGERMACHER: The state is Kamiena.

CARGAS: And where are you from?

E. RINGERMACHER: The same town.

CARGAS: The same town. Did you know each other before the—

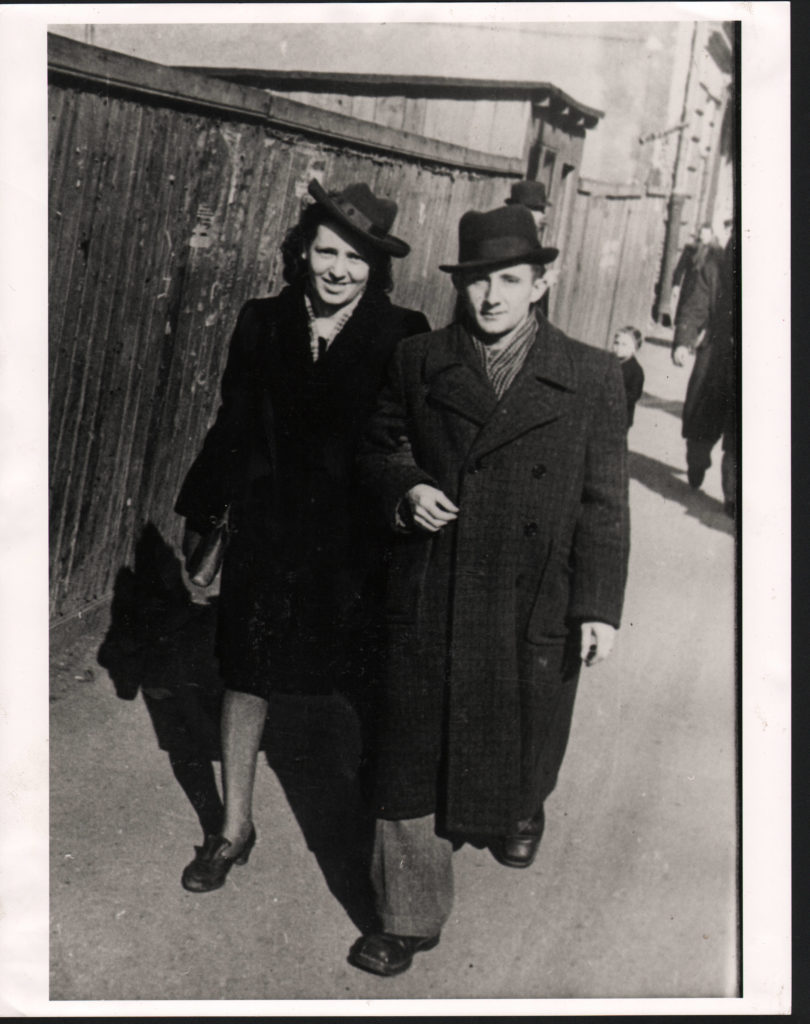

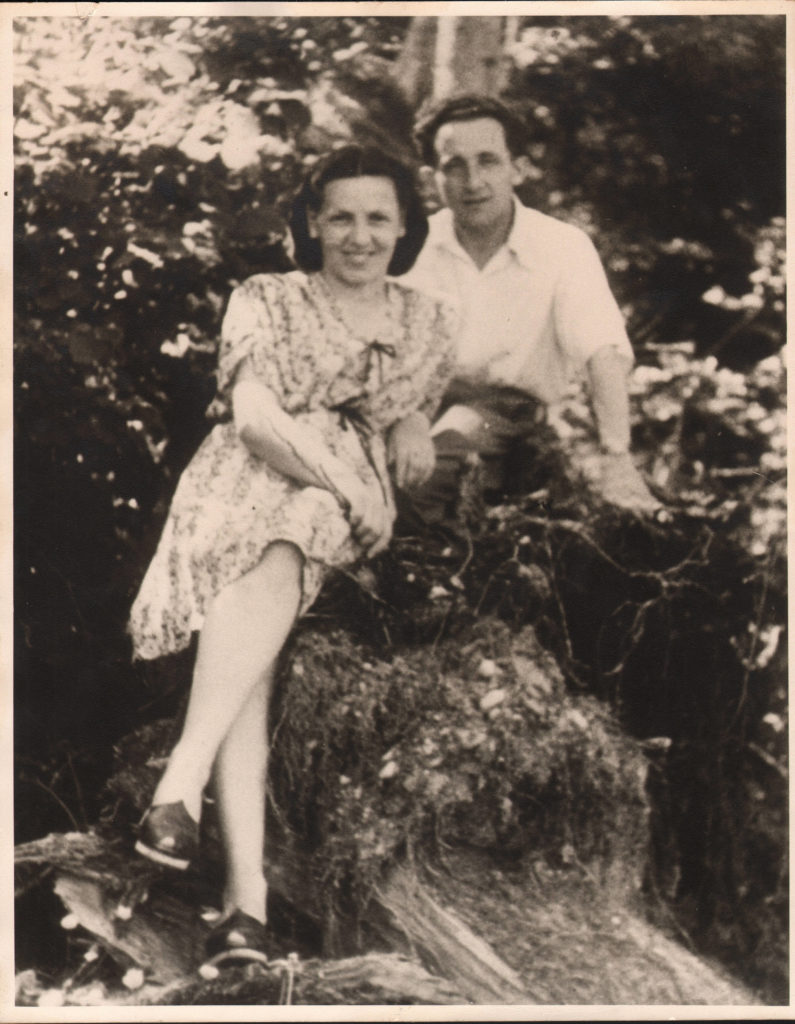

E. RINGERMACHER: We was married in 1940.

CARGAS: So you were separated in—

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah. We was married in the ghetto.

M. RINGERMACHER: We was taken together but separated in—

E. RINGERMACHER: In 1942—

M. RINGERMACHER: In 1944, by the end of 1944, they took you, and you were in concentration camp in Skarzysko ‘til 1944, and by the end of 1944, they took us out from Poland, form Skarzysko, to Germany. They took her to Leipzig, and me they took to Buchenwald.

CARGAS: How did you meet again?

E. RINGERMACHER: After the war in 1945. He was liberated in May. I was liberated on the 25th of April by the Elbe in Wurzen. And then we didn’t know where to go. So we told, where can we go? Our homeland. We go home, like everybody thinks, “Well, we’ll go home, back to Poland.” And we thought, you know, the whole town, you know, all the neighbors, all the people over there, they’ll take us with open hands. You know, we survived after the war. So I was together with my sister and my mother. My mother was in camp with me, and my sister was in camp with me. And when we was liberated, we saw a big train going from Germany. So, we didn’t have nothing to lose. We jumped on the train because we was harassed from all the sides–from the Russian soldiers, from the, you know—after the war. So, we jumped on a train–on a open train, on a open train.

M. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, is a freight—

E. RINGERMACHER: A freight train, yeah.

CARGAS: A freight train.

E. RINGERMACHER: And we was sitting on the train, and no matter where he go. Everything was broken, you know, so he went one kilometer ahead and three kilometers back (LAUGHING).

M. RINGERMACHER: The rails were broken.

E. RINGERMACHER: He went back and forth, but we didn’t care. We was safe at least on the train. A bunch, you know, we got together, whoever we met. We got together and jumped on the train. So we was on the train going back to Poland to find out that the train gonna go back to Poland. So we went back, and we finally, after a few days, we came to Poland, and we came to our town, to our hometown. So we came to our hometown, dirty—and you know how we looked from concentration camp. Well, we found some clothes on there, and we changed the clothes because in camp we had those special outfits, yeah. So we changed for private clothes, and we came to Poland and into our town. And then we asked—we came to the edge of the town. We asked over there, Polish people, “Is there any Jews in here back?”

And they said, “Yes, it’s a few back.” But the minute they saw us, “Why did you came back?” This was the first thing. “We thought that you were not living. Why did you came back?”

So we saw that we got nothing to talk with them, but anyway, they told us there’s a few Jewish people around, and they told us where. And we went over there to those few Jewish people and—the city hall from our town gave those Jewish people a few apartments where to live in, and like concentrated in a few places. Here there are a couple Jewish families in one room, over there on another street was a couple Jewish families—not a couple, was a room with ten Jews in one room because they was afraid to go out. And when WE came, when WE came, we found over there those families, and one lady said to us, “Come and live with me. I got two rooms, and I’ll give you one room, and we’ll have one room.”

CARGAS: A Jewish lady.

E. RINGERMACHER: A Jewish lady, yeah. And we went in, and we was lucky that we got that apartment with a Jewish lady because this was like in a—how you say?

M. RINGERMACHER: A square block. You know, it’s not like here.

E. RINGERMACHER: It was like a garden apartment.

CARGAS: Uh-huh, I understand.

E. RINGERMACHER: You know, garden inside like a garden, three apartments like this. In front was the Russian military station.

CARGAS: Oh, yes, headquarters.

M. RINGERMACHER: Headquarters.

E. RINGERMACHER: Headquarters—

M. RINGERMACHER: There was like they call KGB. What they call?

CARGAS: They call NKVD.

E. RINGERMACHER: NKVD, yeah, that’s right. This was in front of this—our apartment.

M. RINGERMACHER: The guards, they took guards over there all the time.

E. RINGERMACHER: And we was living behind. So we was lucky that time because we was living there how long? Since—

M. RINGERMACHER: We came there in—you came ’45.

E. RINGERMACHER: We came May, ’45.

M. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, ‘til the end of ’45.

E. RINGERMACHER: ‘Til September, I guess.

CARGAS: And that’s where you met?

E. RINGERMACHER: No, no, no, no, no—one month later my husband came to the same place.

M. RINGERMACHER: I thought the same thing.

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, he thought the same thing, “Let’s go home. We’ll meet the family over there.”

M. RINGERMACHER: “Maybe my brother is back”, because I had two brothers, and one got–

E. RINGERMACHER: One didn’t survive.

M. RINGERMACHER: One did not survive. They took him from—and he was in Buchenwald, too, but I heard in March, 1945, they took him from Buchenwald to Mauthausen, and he did not survive that trip. They killed him. Not just him, but the whole transport.

E. RINGERMACHER: The whole transport.

M. RINGERMACHER: Now, though he did not survive, and one brother who was in Russia, he came back, and he is here. But I lost a brother and my mother got killed, too, by the Germans. And my sister—

E. RINGERMACHER: The whole family.

M. RINGERMACHER: The whole family. That’s all I have left, one brother at—

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah!

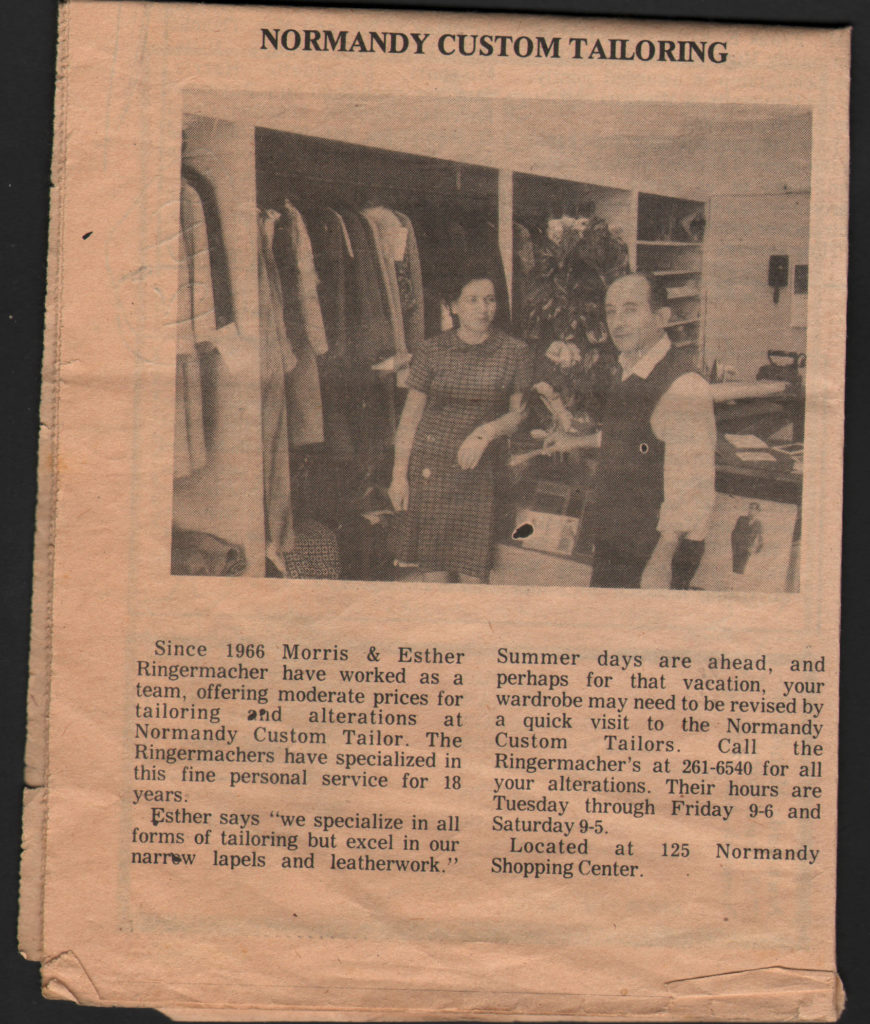

CARGAS: At the garden apartment?

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah. One month later, my husband showed up. So we was lucky then. We was very happy, and we was living over there in that apartment. In fact, we had to make a living. I was a dressmaker from before. I learned how to sew, dressmaking. I learned during the war. I finished school, and then I went to learn something. We had to have, you know, not like here, you think about college. Over there we was thinking about a trade to make a living. So I learned how to sew, and when we came back, a lot of those Polish people knew that I am back, and they came in to me. They brought something, you know, to work for them. Okay. One morning a lady runs into us, “My God, my God, you alive. I am so happy you alive!”

I said, “What’s happened?” And she was all shook up. I said, “”What’s happened?”

And she said to us, “Go away from here because they killed ten people. They killed ten people in the next apartment!”

M. RINGERMACHER: And they were survivors.

E. RINGERMACHER: Ten survivors.

M. RINGERMACHER: They survived Hitler, survived—

E. RINGERMACHER: They survived all the concentration camps, Treblinka—

CARGAS: The Polish people?

E. RINGERMACHER: The Polish people. One man was—he jumped out from the wagon, from Treblinka when they took him to Treblinka. He jumped out, and he came back alive. The other ones all over. So they get there it was ten people in one house. A few Polish people got at night into them, killed them one by one.

M. RINGERMACHER: With a machine gun.

E. RINGERMACHER: With a machine gun—with a machine gun was it?

M. RINGERMACHER: With a machine gun and with the pistols. One was from the militia—he got a machine gun.

E. RINGERMACHER: It was like, it was like—

M. RINGERMACHER: One from the Polish, Polish militia.

E. RINGERMACHER: Eight men and one woman was between them. They all got killed. So when this woman come to my apartment, we was lucky because the militia, the Russian militia was in front of us. So we got somebody.

CARGAS: But the woman who warned you. Was she Jewish?

E. RINGERMACHER: No. She didn’t, she didn’t—it was in the morning, it was next day. She just came up to tell us what’s happened, yeah. We didn’t run away, but we wanted to find out. We didn’t run away. What’s happened, we find out what’s happened, and we even made a funeral for them. And we was attending the funeral. All the rest of us who survived, we went to the cemetery with the Russian militia watching us with pistols. This was after the war in mine home town! With militia watching us, we was afraid to go alone to the cemetery.

M. RINGERMACHER: The Russian militia was supposed to watch us.

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah. And we buried them.

M. RINGERMACHER: That nothing shall happen in this same Polish town.

E. RINGERMACHER: To us, yeah. So a few months later—a couple—I don’t think too long–

M. RINGERMACHER: A few weeks later—

E. RINGERMACHER: A few weeks later we left our home town. We moved out to a big town, to Lodz. That’s the second big town in Poland—Warsaw and Lodz. And then we stayed in Lodz ‘til we went away altogether from Poland. They find out who killed those people. They found was a woman involved of it.

M. RINGERMACHER: And the Russian, maybe some of the Polish government—they caught them.

E. RINGERMACHER: They caught them, yeah, the whole bunch.

M. RINGERMACHER: A few they caught. One was executed, and I think that the lady was executed.

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah.

M. RINGERMACHER: The lady was executed, and the two other people, they got prison, three or four years, I don’t know, but they caught them.

E. RINGERMACHER: They caught the whole bunch of them. And then in the big city we was so afraid since then, we kept the door locked even in the big city. We was so afraid that we lived each day. We was very frightened, and then we—

M. RINGERMACHER: And except this—not just—on the whole we were afraid that still it is left from before the war, you know, the hate, the hatred for Jews.

E. RINGERMACHER: The anti-Semitism.

M. RINGERMACHER: The hatred on Jews. It still was the same thing what it was before the war and after the war. You can’t change those things overnight.

CARGAS: And yet they knew what happened to the Jews.

M. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, and we—

E. RINGERMACHER: They helped them.

M. RINGERMACHER: They knew and we knew that this will go on and on, and the same thing. It’s no use to be over there, so we decided to leave Poland.

E. RINGERMACHER: To Germany—

M. RINGERMACHER: –and to see where we will go from over there.

CARGAS: That’s interesting. You went from Poland to the home of the Nazis.

E. RINGERMACHER: To West Germany, to West Germany.

CARGAS: I realize that.

M. RINGERMACHER: At that time, Russia was over there, you know. This was not Germany at that time. It was like a liberated country.

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, and they had like the peace, you know, special concentration camps—not concentration camps—

M. RINGERMACHER: No, camps.

E. RINGERMACHER: For the—

M. RINGERMACHER: For the leftover—

CARGAS: Displaced persons.

E. RINGERMACHER: For the displaced persons.

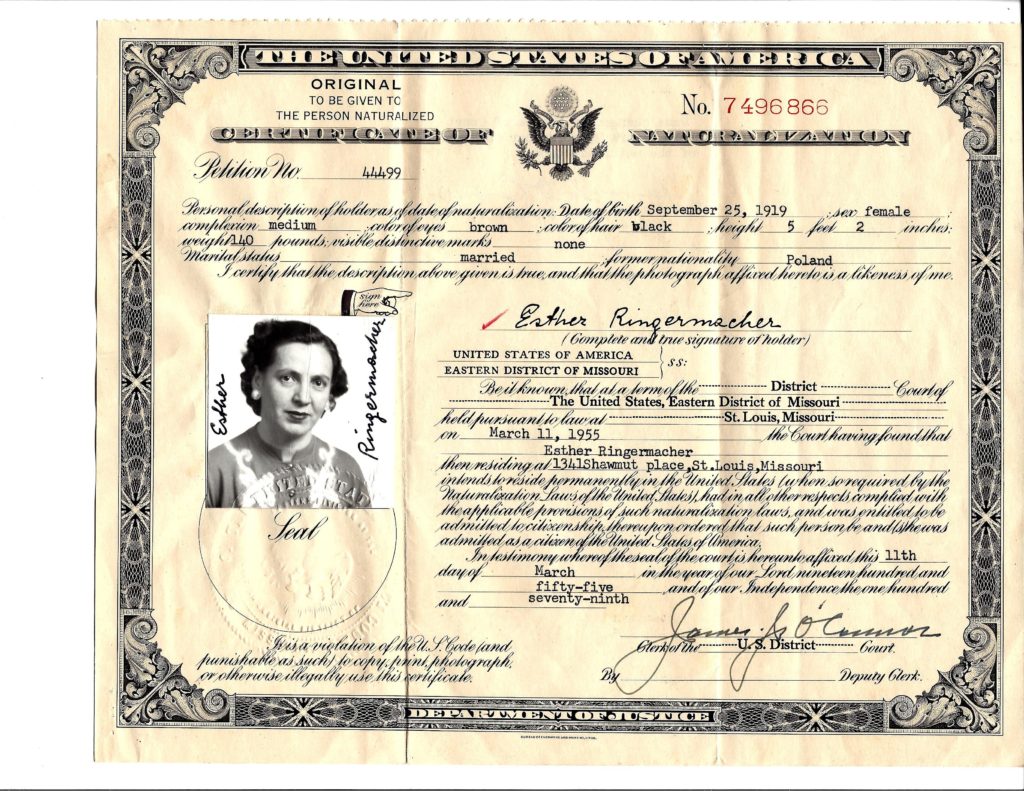

CARGAS: And then you came from Germany here?

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah.

M. RINGERMACHER: From over there, yes.

CARGAS: Right to St. Louis?

E. RINGERMACHER: Yeah, and so we stay in St. Louis.

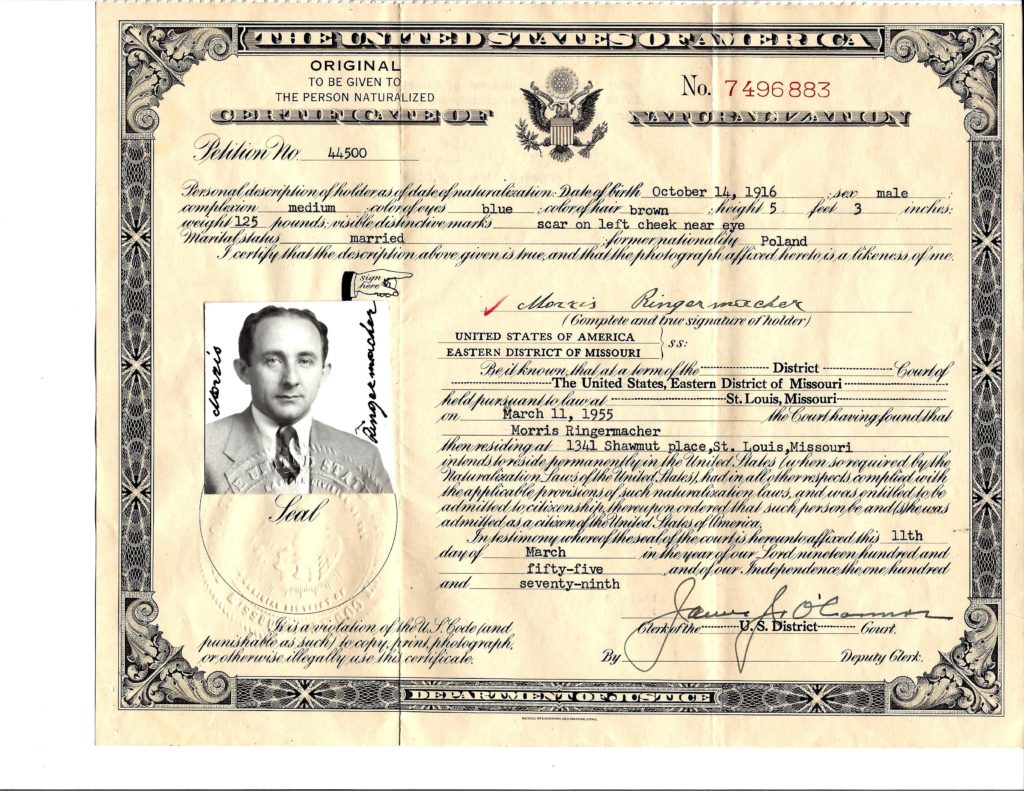

M. RINGERMACHER: We got sponsorships from here.

CARGAS: I really want to ask you because of the purpose of this book and the direction I think we must speak about is what do you think about Christianity?

E. RINGERMACHER: I told you now one fact. I told you this one fact what will live over after the war, after all the concentration camp, and this was all Catholic people, Christian people. Poland—I think Poland with the whole religion in Poland mostly was Catholic—Christians, Catholics.

M. RINGERMACHER: Ninety-five percent.

E. RINGERMACHER: And I think that this—I don’t know, maybe your ancestors was from Poland, but you’re writing a book. I wouldn’t say this to any other person, Polish person. You know, I don’t hate the Polish people what are in here. They are changed; they are different; they changed, but I can tell you that I would never go back to Poland, see Poland. Poland for me is blood because the Polish people, for me, they helped the Nazis more than any other country. They helped. This was—they didn’t build the concentration camps. They didn’t build the gas chambers.

M. RINGERMACHER: The gas chambers they built in Germany.

E. RINGERMACHER: They didn’t build in France; they didn’t build in Holland; they didn’t build in Czechoslovakia. They built all the gas chambers in Poland. Most of the gas chambers was built in Poland: Auschwitz, Treblinka. Everything was in Poland.

CARGAS: Why?

E. RINGERMACHER: Because it was in cooperation with the Polish people. I don’t say maybe it was one percent good.

CARGAS: Not all of them–

E. RINGERMACHER: Maybe one percent. A few people.

M. RINGERMACHER: There were a percent, I can say I don’t know if more, but there were people who helped and who hide a few Jews over there.

E. RINGERMACHER: Us for a few weeks or so. Maybe one percent. I can even think one percent, but most of them.

M. RINGERMACHER: This one percent is lost between those others.

E. RINGERMACHER: They was afraid. They were afraid. It wasn’t like now. Now people all over the world speak out for humanity. They speak out for a free world. At that time, everybody was afraid. That what’s happened. Even–I say that’s why it’s happened to us, too. If we wouldn’t be afraid, wouldn’t be the Treblinka and ashes. They would stood up like the Warsaw ghetto did. But the Warsaw ghetto was the last. They saw that’s happened all over, but we didn’t know what’s happened. We was afraid for any little thing. We had the Germans. We had the Poles. We had like—I’ll tell you one thing—

M. RINGERMACHER: What’s the difference? I wouldn’t go, I mean, in the concentration camp not to get up and do something about it. If I would know that behind me I have the Polish people who will—if I will go in the forest or hide or make like—

E. RINGERMACHER: They would help me.

M. RINGERMACHER: Groups to fight back.

CARGAS: Resistance groups.

M. RINGERMACHER: That’s right. I would take a gun or something, and get in groups and go into the forest and fight against them if I would know if I have behind me my people. Means the Polish people, if they should not say, “Oh, here, here they are. Here they are.”

E. RINGERMACHER: You know, in ghetto, we had one street to walk. You know, maybe ghetto, one street to walk if—

M. RINGERMACHER: The Germans did that.

E. RINGERMACHER: One girl and a boy went for a walk, so I don’t know, maybe they had somewhere to go. They went out of the ghetto a block or two blocks behind the ghetto. So one Polish guy saw them, and he knew them. That was a Jewish girl and a boy. They called right away a German. “Those are Jews!” And you know what they did? They took them away. And the next day, in the morning, they made that boy run through the whole street, and they took a German shepherd run after that boy and tear out pieces from him—tear off his clothes and tear out pieces. Can you imagine this? (LONG PAUSE) That’s what I remember. Our—the “middle” Poland was bad. Congress Poland was very bad. Maybe somewhere in other–in other states– because it was a few partisans what they survived in the–

M. RINGERMACHER: In the forest—

E. RINGERMACHER: In the forest. What maybe they ran out, and they gave them some food, but not in our—in the center of Poland. This was the worst what I remember. I cannot tell you anything good.

CARGAS: And do you still—I want to be careful with these questions—

E. RINGERMACHER: No, no, I am the same.

CARGAS: For example, towards Christianity in this country—

E. RINGERMACHER: It’s nothing; it’s different.

M. RINGERMACHER: Here you don’t have that hatred. See, over there, the hatred they gave in to their generations, their kids, the hate right from the beginning, from the start. They raised them like this.

E. RINGERMACHER: The churches, the churches, and all the schools, and all the churches. They was teaching religion in the schools.

M. RINGERMACHER: They raised them that way.

E. RINGERMACHER: In all the schools they was teaching the Catholics that the Jews killed Christ.