SCHWARTZ: And this time I was there in this room, was no air comin’ in, only a little bitty window, I would say one foot by a foot and a half. In the morning when they opened the door to let you out to the bathroom, you was, you was fallin’ down in the hallway, you was getting dizzy, the dizzy spells from lack of air, see.

PERRY: Sure.

SCHWARTZ: The food consisted of a piece of bread; I believe 12 to a loaf, 12 slices to a loaf. Each one had a little slice and a little watery soup. And how the soup was given to you is worth it to mention. The door opened up, a guard came in and he ask, “How many?” And you say, “32,” or 30. This was the door over here and you had to stay right over there, facin’ the door, like in a half a moon.

PERRY: A semicircle.

SCHWARTZ: Yeah. He put in one…

PERRY: Ladle?

SCHWARTZ: Ladle, and hand over the man, the first one to his right. This man had to take it out of there, a drink from the soup and hand over the bowl to another one; it goes around. In another hand he put in another soup, another bowl – 32 bowls all the way around had to go, ’til the bowls was empty. The bowls was empty when he was through, see. And if you didn’t had enough, if you didn’t took what you want, you was out of luck. You didn’t eat no more, see. This was a device in the German culture – modern German culture, I would say. That’s what he used to call us in these rooms, see, the modern German culture. You eat on the run, that’s what you call it, see.

So, after bein’, after there, in Poznan, the room was so dirty. There were cockroaches was eatin’ us up. Your skin was just like a – your skin like a file, you know, ______. The lice was eatin’ you up; they sucked your blood out.

After this, one morning, after five weeks or six weeks or somethin’ like that, I don’t remember exactly how long I was there, they took us – on each floor was a big cage with iron bars. And they called out the name and you had to run, taking your belongings what you had over there – a coat or something. You runnin’ to the cage, ’til they got about a hundred people or a 150 people, took you downstairs, they give you a shower, put you back on trucks, took you down to a siding and they packed you in railroad cars. This time they put you in, like in a passenger car, but the seats – you took out everything – there was nothing but bare walls and wooden benches was there. And, we know that we goin’ now all the way to Auschwitz. Auschwitz – in Polish they call it Oswiecim. So, this was about six in the morning we starts off and we went in this car, and everybody was sittin’. We has one guard by this door, one guard by this door, already with a machine gun. They had a car with women too. The door, this car had a toilet – the door was taken off, see. The guards could see you. The windows was with barbed wire – lace with barbed wire, and it was all kinda…

Well, finally, it got about eight o’clock in the night, was dark already in August, I know it was August. I didn’t know when. Later, I found out it was the 19th, they land us in the paradise of Auschwitz. Well, they starts to holler, “Everybody raus,” everybody has to get out and they had, like ah, like, you have to run through a row of SS mens and this side, everyone of them with the rifle butts was hittin’ you doggone where he can ’til they got everybody out. Lined ’em up, was 150 of us, about 145, I believe, and they took us, “Forward march,” everybody has to march. We knew we goin’ to the camp. But, outside the station was waitin’ for us over there a surprise – SS men with the dogs. Oh, they joined up, see. We got through. We got down the street. The streets was deserted. You didn’t see nobody on the street, no light, it was dark and the dogs was jumpin’ on you. They put them the dogs on long leash. They was walkin’ the sidewalk and the dog was jumpin’, the dog was – he musta been trained to rippen your clothes off only. You see, he didn’t bother your flesh, only the clothes, they rippen off you. I had a shirt, I remember, a blue shirt and a pair of dark slacks and when I – you know, a half an hour later, was nothing there, (LAUGHTER) honestly but the boots. I was almost naked, see. When the dog got a hold of you and he couldn’t rip you loose the clothes, he dragged you on the sidewalk and right away a burst from the machine gun, rat-ta-ta-ta-ta. That’s where you went. That’s all there was to it. If the dog drag you on the sidewalk, it mean you are tryin’ to escape, see. “Ta-ta-ta-ta-ta” this was all for you. I was there and I remember. About, I believe approximately what I saw was five, six of them was laiden out. The dogs was draggin’ them. You know, there to the camp, see. You had to have the number, see. You know the German Punktlichkeit.

PERRY: Yeah, it has to be exact.

SCHWARTZ: You know, exactly by the number. Even a dead person has to be counted, see. So, those dogs were draggin’ those dead bodies. And I got, turning, turn around the pants after half an hour walking through a lane and I remember a street – grown with trees, a beautiful street. It must have been a nice little town, Auschwitz, before the war, just like a lane. On both sides the street mit trees, and we were around comin’ around the bend and finally we see this doggone camp, boy. Auschwitz is there already here. This is home sweet home, see.

PERRY: Had you heard about it before?

SCHWARTZ: I heard, in Djaldovo, in Soldau, and they leak this out.

PERRY: So, information has leaked back to you.

SCHWARTZ: That’s right. The information in Soldau they told us that _______ in the Reichs marshall, or something, the Reichsfuhrer, Himmler, that’s I was already know to reporten to, to the KL, they used to call the konzentrationslager Auschwitz, year 1942, you know…

PERRY: But did you, as a Jewish person, know what the inside of a camp like that was like before?

SCHWARTZ: We heard something but we didn’t know it’s here.

PERRY: You couldn’t understand then.

SCHWARTZ: Well, let me tell you before the war when I was in the Betar and Hitler marched in to Austria again, they took the Jews too and put them in a little Mauthausen; it was just the beginning, the beginning Dachau, the beginning. They say they took them into concentration camp. They was doin’ some kinda little work, you know in this, but mostly of them, they was asking for the money. Mostlythey was askin’ for money, somebody has the money they can go buy themselves out – they let him out, they shipped him out, you know, someplace. That’s what we thought was a concentration camp.

But, when I arrived at Auschwitz, Auschwitz was no more a concentration, it was a death camp. Before me was already about seven, eight, or 10 transports of Jews comin’ in from Holland, Belgium and Paris. And in France came in already; they all got liquidated.

PERRY: You only found out about that afterwards.

SCHWARTZ: Afterwards, that’s right. I didn’t know it, see.

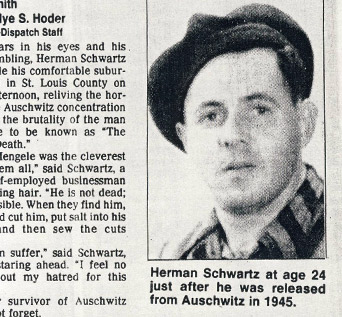

So, we stand before the gate and I read on the top: Arbeit Macht Frei – freedom through work, and I looked in and I saw these beautiful buildings. And the windows was open, was still light on in the buildings and I see they got white linen, there you sleep on white linen. I says to my mine, mine, ________, I say, “Get a look over here, we arrived over here in a paradise,” (LAUGHTER) I said. He says, “Boy, we find out right away what kinda paradise is, (LAUGHTER) doggone thing is, you know. I said, “Well,” I says, and all of a sudden – all of a sudden a car pulls in, a convertible, see. I see this, a convertible, see. Jumps out an officer, I didn’t know it, and he comin’ over and says, “Who’s over 55 years of age? Step out.” Steps out about 15-20 of them stepped out, mostly Polish, a few Jews too was there, I believe. And, he tell them to marchin’ over there, to stand up over there on the side and a few minutes later they was talkin’ over there, with the guy in this little shack by the gate. And all of a sudden he says, “Well everybody falls in, eintreten,” and they march us in – in the camp to the bathhouse. This was nine o’clock in the night, already, see. I didn’t know that this was Mengele. Later I find out.

PERRY: So, that was Mengele then?

SCHWARTZ: A little introduction. “Over 55,” he says, “I refuse you to go in the camp,” he says. He’s goin’ fix ’em right now. He’s a Nazi, that’s all.

So, they got us into the bathhouse and we was waitin’ right there. I forgot the number from the building. And, next morning, next morning about seven o’clock, came in after the appel, the sorta appel what goes on in the camp. The bell was ringing, and everybody was linin’ up. They count ’em in the morning, they count ’em in the evenin’. And, later the guys came in that was workin’ in this bathhouse, they all came in, the guys. Say, “Okay, fellas, we going start off to processing you. Take off your clothes, put ’em all in, hang ’em up on a little doggone thing, put ’em in in a paper bag, and go over there to this table and we will give you a ticket and you will slap on this and you clothes right there. You got to have – you got the clothes to stack yourself, see. Later, down the way, nobody’s somethin’ is missin’. Missin’ from your stuff.” They told me it’s a political prison. In other words, it’s a _______, it’s only the political prisoners that has this honor…

PERRY: The privilege of stealing their own…

SCHWARTZ: And he says, “And now we goin’ shavin’ you and this and this.” And he says to me, “Everybody has to dip in in this bathtub over here.” I looked in this bathtub, I didn’t know what the heck is there, in this bathtub. So, I got in and he push me down over the head. That was raw lysol. My skin was so chapped up from these prisons’ whole thing.

PERRY: Caustic.

SCHWARTZ: And this lysol, boy, almost drove me crazy.

PERRY: Sure.

SCHWARTZ: I almost run in with my head to the wall, see. It burns. And the other guys, the same way. Boy, you heard about it was bitin’ the fingers. And some of them was lying down, raw lysol, something. Lucky, one little tap was drippin’. The shower, the showerhead was ______, hangin’ down and pipes and this one was drippin’ a little bit. Everybody was tryin’ to get under this water. They kill each other almost right away, see. Finally, he turn down the water.

PERRY: He turned down the water?

SCHWARTZ: Yah, he turned down the water and he start the doggone… Boy, I remember this doggone, what you call it, this bathtub. I don’t wish nobody if you went lookin’ for pain, was pouring in the open wounds and you walk in in a bathtub of raw lysol.

PERRY: Yeah, it’s caustic.

SCHWARTZ: And this almost drove a man crazy, see. I don’t know how we got out alive from this thing.

So, after they got us already rinsed down this thing and they started to process – to give us – the shirt, pair of pants.

PERRY: Prison clothes.

SCHWARTZ: Prison clothes, stripes, with a little cup. And all of a sudden he hands me two, two wooden shoes, like in Holland, the wooden shoes. And I said to myself, I says, “Oh brother, I’m not goin’ wearin’ this,” I says. “Man, man, man,” I says, “you can get killed” – (LAUGHTER) you couldn’t even walk with this. So you got to have this, a newcomer you got to wear this, see. So, I don’t have no choice. They took away my other shoes and they put it in the bags, see.

PERRY: Sure, you sealed it yourself.

SCHWARTZ: Yah. I put ’em on and all of a sudden they start to rub my feet.

We standin’ outside. Three tables they put up to register us. All of a sudden comes down one SS man. Later we find out who this is. He’s givin’ us a speech.

PERRY: Mengele?

SCHWARTZ: No, this was that Pallisch, they killed him – his name was Pallisch. Pallisch – Gerhardt Pallisch was his name. He played a big role. He killed thousands of them over there, man, man, man, this murderer. So, he stood right over there on the third step of the building where the bathhouse was and he says, “Okay, you dogs, you arrived,” – and well, I’m tryin’ to tell this in English.

PERRY: Sure.

SCHWARTZ: “You arrived over here in KL Auschwitz…”

PERRY: KL?

SCHWARTZ: Yeah, KL, konzentrat –

PERRY: Oh, oh, oh, KL (OVERTALK)

SCHWARTZ: Yeah, KL Auschwitz. And he says, “Here if you behave yourselves and you work good, you livin’ from two days to a week. (PAUSE) Any rabbis over here between you, rabbinas or priests? You livin’ only 24 hours,” he says. “And the rest of you dogs, one month – six weeks, the most. Nobody escapes from over here, only you goin’ through with this big chimney you see over there.” There was an old crematorium sittin’ right there by Auschwitz where they was burnin’, burnin’ the old bodies from the hospitals, from the dead ones. He says, “Through this chimney is the only way out.” So I was standin’ over there and I raise mine eyes to the, to the Almighty and I says, “If that’s is mine end already here,” I says, “there is nothing I can say, dear God,” I says. (PAUSE) And he went away. He had a whip in his hand, I remember, he was hackin’ against his boots. He walked away and all of a sudden I see a man walkin’ – a big man walkin’ from over there, from the street, from the camp, walkin’ to our group, you know, between – by the bathhouse and he says, “Anyone here from Warsaw?” I says, “I’m from Warsaw.” And to mine dismay, I look around and I see a big man and I look on him and he looks on me. He says, “Chamek?” I says, “Vladek.” He calls my name and I was callin’ his name, see. Vladek.

PERRY: Vladek is his name?

SCHWARTZ: Vladek was his name.

PERRY: And your name was?

SCHWARTZ: He called me Chamek – Chaim.

PERRY: Oh yeah, okay – Chamek. I understand.

SCHWARTZ: He was workin’ for my uncle – he was a deliveryman. He was a delivery man and I helped him in makin’ his contraption – this, this little cart, and hookin’ up to the bicycle. He was deliverin’ in my uncle’s – to the stores.

PERRY: Sure.

SCHWARTZ: He says, “What the hell you doin’ over here?” I says, “How long you been here?” I ask him. He says, “Don’t worry about nothing,” he says, “I’m here.”

PERRY: He was a…

SCHWARTZ: He was here a long time. He was from the Polish officers who came over here. He was not an officer. He found a uniform from a killed major, he put on, see. He was only a corporal, see. And he thought, like in the First World War, that officers the Germans don’t kill…

PERRY: Sure, they’ll treat them well.

SCHWARTZ: He didn’t know it, but this war was the opposite way around, see. They killed all high-ranking officers. So they kept, you know, to a corporal this…they let him through, you see. So, he got, he got (LAUGHTER) caught…

PERRY: Caught in his own plan.

SCHWARTZ: In his own web. And he’s tellin’ me the story, he says, “Don’t worry about a thing,” and he looks at me and he says, “Chamek,” he says, “boy, you lookin’ like a man done gone out to the grave already.” I went down from 160 pounds…when I weighed, I was almost about 87 pounds.

PERRY: By that time you were 87 pounds? Wow.

SCHWARTZ: I was nothin’ but a skeleton. He says, “You know what, the first thing what I’m goin’ do, I’m have to feed you a little bit,” you know.

PERRY: But, how did he get food?

SCHWARTZ: Well, you see, there so many people got killed in this camp, so much soup left over…

PERRY: Oh, they didn’t know who was…

SCHWARTZ: So much bread was left over – people everyday got killed. You know, it was laden, in the buildings was laden so much soup, you see. He says, “Well,” he says, “get through first over here, this registration.” And he was tellin’ me, he says, “You speakin’ the German, why you don’t tell ’em that you (LAUGHTER) you are a German?” I says, “Are you kidding, man? Do you want me to get killed? They goin’ catch me, a Jew, telling he’s a German – do you know what goin’ to happen to me?” I says, “They goin’ to hang me right over here in this building.” He says, “Well, okay, but you can say you Polish.” I says, “What, with my name, Schwartzwald?” He says I can say Polish. “Well, you must be sick in the head,” I’m tellin’ him. He says, “Well, you can do no better,” says, “Say you’re Jewish, that’s all.” He says, “I’m here, don’t worry about anything,” he says. I says, “What you mean, you here?” “I’m goin’ bring you some food and goin’ fill you up a little bit.”

You know, in two, three weeks, doggone, I gained about 15-20 pounds. I believe I was the only Jew in the history of Auschwitz what was gainin’ weight in Auschwitz. (LAUGHTER)

PERRY: How come he had the food available? Why didn’t the other people have the food?

SCHWARTZ: Well, like they brought in five barrels of soup. Was about a hundred people was sick, they couldn’t eat. And a hundred of them was dead already – couldn’t eat. This soup was there on the belt. All he had to do was dippen in with a bowl and bring it over to me, see. That’s what he did, see. And sometime a piece of bread too, see.

PERRY: Was he in another barracks?

SCHWARTZ: He was in another barracks.

PERRY: I see.

SCHWARTZ: But, well, we goin’ across, I will show you the whole thing what we did, see. So, they registered me over here and the political prisoners they didn’t tattoo right away – only the Jews what came in on the transports, they tattoo. The political prisoners they didn’t put the number on there right away, see. So I was goin’ without a number, see.

PERRY: Then you were considered a political prisoner because of your education?

SCHWARTZ: That’s right, that’s right. I was considered a political prisoner.

PERRY: Even though you were Jewish?

SCHWARTZ: Yah, yah. I got, I got through the Reichsfuhrer, through Himmler, the schuzebefehl, the papers.

PERRY: It says you’re a political prisoner.

SCHWARTZ: I’m a political prisoner.

PERRY: I see.

SCHWARTZ: And I told mine other Polish around me, you know, the guys from the same city, I says, “We got a little help over here, maybe we can…it’s not so black, like it is…Maybe, maybe somehow we – God will have mercy on us. Maybe we can still get out from this. Oh,” I says, “He’s with you all the time. Your spirit is all the time how you see how black it’s getting you all the time. You’re not givin’ up yet.” I says, “No, I will never give up,” I says, “that’s what keeps you alive,” I says. If you given up, you heard what they said, two days and you goin’ be dead. Many of them died in two days. Some of them didn’t make it even two days.

So, after I got dressed, and they give me those wooden shoes, and I got registered and they put me with a piece of some kinda of a pencil, they mark a number on your chest, that you (LAUGHTER) don’t forget. ’Til you gotten in the Block, they give you here a piece of – a number and put you on the pants over here a little number. So they took us first in Block Seven; Auschwitz, the camp was divided and between this was a – a concrete wall, see.

PERRY: In the middle of the camp.

SCHWARTZ: In the middle of the camp, see. And they had to make an entlausen to kill the typhus. So one side was already cleared up, cleared up, and the other side was not yet – still sick. So they put us in Block Seven in the top. I was there one night. Next morning he says, “What’s your call of profession?” He says, “What’s your profession?” “Well,” I says – instead of sayin’ I’m a chemical, I’ll say I’m a carpenter. He told me, he says, “Get away from those convicts,” he says. “Get away from those blokes and get hooked up with a working group.” Then you gotta bigger chance to survive, you see.

So, I raised my hand. I says, “I’m a carpenter,” and I says, “I’m also a mechanic.” And they took us from the block to another camp on the other side in Block 19, see. I got into Block 19, this was not the working block yet, see. Was a – son-of-a-gun – a German, a six footer with such a big muscles and tattoos all over him. And he was making sport with us. After the pill in the morning, he put us down, you know, _______…This is worse, sittin’ like that, to sittin’ in…

PERRY: Oh yeah, oh yeah. After a while you can’t move.

SCHWARTZ: One day, two days, three days. Finally, doggone, I say, all of a sudden I says, you know, comes by one guy, he says, “Look, they need carpenters, you’d better get over there and go in this Block, this building over there, the registrar. They gonna take you out from this Block, put you in this one, you see. You are goin’ out with a kommando, D.A.W.” D.A.W. they call it Deutsche Ausrustungs Werke. What they doin’, the carpenters, painters, you name it, schlossers and they got oh, all kinda what you call it – professionals.

PERRY: All kinds of skills.

SCHWARTZ: Skills, yah. Well, we got in in this building in the night. And they put us on the top. They call it, the bottom, they call it 18. On the top they call it 18 R – 18 A. All of a sudden we laden down our bones already to sleep and all of a sudden, in the night, “Everybody raus,” you know, eintreten. What the hell is goin’ on, they don’t let you sleep in the night? Day and night is goin’ on this thing. So, eintreten’s on…eintreten. They don’t tell you, but they had about 150 of us, mostly Jews. And they marched us to the gate. They marched us to the gate and they marched us out close to track, and all of a sudden they’re gone. And I find myself between, between packages, valises and this, bags – people from the transports, was comin’ in the Jews, see. So, finally, I got in touch with other prisoners, French Jews mostly and I says, “What’s goin’ on here?” He says, “You don’t know.” I says, “I just got in yesterday and I don’t know,” see. He says, “Here is this place where all the transports arrive.”

PERRY: The transports?

SCHWARTZ: From Paris we just had one transport. It’s comin’ in another one, stays over there in the city of Auschwitz on the siding. We’ve got to clean up this and then comes another one. I says, “What the hell goin’ on over here, what they doin’.” He say, “Don’t you know, that’s a bad camp – Auschwitz – they killin’ them with gas.”

PERRY: They knew.

SCHWARTZ: Yah, they knew. I didn’t know it, you see. He says to me, “You didn’t this, Auschwitz, this is a death camp?” I says, “No, I just got in here,” I says. He says, “That’s what’s is. They got over there a little house and baths, people takin’ off clothes and with machine gun they run them in this building. They turn on the gas and locken up the doors and turning on the gas and later they burnin’ the corpses over there, you know.” Boy, I got so shooken up, I almost got the diarrhea. He says, “Who told you – why, why did you came over here to work?” I said, “They took us out in the back in the night. I didn’t want come; it’s not my own free will…” I met a bunch of French Jews. They came from Poland, the border of Poland and they moved them to, to Paris. And it looked like they brought them back from Paris – all of the Jews were born in Poland, not from France. Some of them came from Turkey, everything…

PERRY: Fled to France.

SCHWARTZ: Yeah. So they tellin’ us, to loaden up those trucks with those packages salamis with bread, white bread.

PERRY: They brought it with them?

SCHWARTZ: Yeah. I says, “They let you eat over here?” He says, “Yah, you can eat all you want. You can drink all you want. When those people get where they goin’, they don’t need it anymore – nothing anymore.”

So, I says to my friends, I says, “Well, what you think we should do.” See, I don’t know what we will do. We’re tryin’ to get out from this if we can, if they let us. One Jew over there says, “You know what they doin’ to this kommando – it’s every three months – they liquidatin’ them, all of them.” Those were the workmen who came in the crematoria. Those were the workmen in the barracks, and those were the workmen over here, see. So, every three months, they liquidatin’ them.

Well, I got back after we got through workin’ about 24 hours. After I got through work, this after this, I got in in the building in my Block, Vladek is lookin’ for me. He says, “I don’t know what happened to you. Tell me what happened to you.” And I keep tellin’ him this is what happened. He says, “Well, don’t worry about it. Tomorrow, tomorrow, you join up with another kommando. _______, you see, they goin’ over there. And if you get in to this kommando then they can take you out ________ from this kommando, to goin’ over there, see.”

PERRY: So you had to get in to the D.A.W.?

SCHWARTZ: Yah, that’s right. “Well,” he says, “I fix this, don’t worry about it.” He went that day to the schreiber in this building, the Block schreiber, and he come back. He says, “Tomorrow, when they call D.A.W., you know, kommando D.A.W., you will be right there mixed up with them, and that’s all there is to it, see.”

PERRY: How did he have so much influence?

SCHWARTZ: He was there already since 1940. ’40, he arrived over there in July of 1940.

PERRY: And he was a political prisoner, so he wasn’t killed?

SCHWARTZ: He was, he was a political prisoner and he went through plenty over there. They killed most of them over there.

PERRY: But, he survived.

SCHWARTZ: He survived, see. He had a good position in the camp. He was in the fire brigade, you see.