Inge Erhard was born July 21, 1935 in Nuremberg, Germany. As a Protestant in Germany during World War II, Inge was a young eyewitness to the Holocaust.

Inge Erhard

Mapping Inge's Life

Click on the location markers to learn more about Inge. Use the timeline below the map or the left and right keys on your keyboard to explore chronologically. In some cases the dates below were estimated based on the oral histories.

Read Inge's Oral History Transcripts

Read the transcripts by clicking the red plus signs below.

Tape 1 - Side 1

P: I want Inge to tell me how it was to live in Nazi Germany as a German child to grow up there during World War II. Tell me a little about your early life, your mother your father…

E: Well, I’m honored to tell you a little part of my story growing up in Germany during the war and after. I was born in 1935 in Nuremburg, Germany. And, my family, I was the first of three girls and my mother and father lived in an apartment and of course everything was very common and normal growing up. We just had a very quiet life. I had a girlfriend living next door and we would play outdoors in the sandbox and things like that.

P: Tell me, what did you do as far as religion, what was your background?

E: Well, my parent s were Protestant but uh, my mother, my mother’s parents left the church because they didn’t want, they just didn’t like that the government took our money out of the paychecks of the church and they wanted to be free of that and I don’t know exactly what they early thought about, they just really didn’t like going to church I think and, uh, my father was a state Protestant, he did not leave the church and he paid his dues, or whatever they’re called to the church all his life. But, both of them left us on our own, like whatever we wanted to, if we wanted to go to church we, we were free to do that even if I was like 4 or 5 years old, uh, I had a girlfriend next door and we would go to the children’s service on Sunday morning all by ourselves. There were only children at that hour and, uh, it was interesting to me) and we just liked going. But then later on I guess we stopped doing that, and there was something called, uh, a free religious organization and they had their own, uh, agenda and I went there sometimes but not very much. And, uh, I believe, uh, that’s all about you know…

P: Yeah, thank you. Um, tell me about your education, what kind of school did you go to and

E: Well, I went to public school and uh, most people, I went only to 8th grade and then I had to go to uh…when you learn a trade? Trade school…I was 14 when I started, when school started and then I went to trade school for three years to become a sales person and that is how they do things in Germany, ____? Our education continues in that, I knew that I was going to do that and then you still had to learn just like your high school you still learn all the, uh the different things that you needed.

P: How many years?

E: Three years.

P: Three years to be a sales person.

E: Yes.

P: You must have been a really good one.

E: Yeah I was (laughter). Uh, and that was in a, I actually had already plans to be in this chain store, it was this chain store for groceries and it was probably one of the first chain stores in Germany and they had their main headquarters in Hamburg. And I lived in Nuremburg and they would get out at, um, things delivered on trucks from Hamburg, and we had, I mean, we had to, uh, while I was going to school, I mean I was working already, and I wasn’t out on the floor, I had to do all the back things like what they do behind scenes, for instance, packaging up all the groceries, the flour, the sugar, and everything that came in stacks, was delivered in back and we had to, we had a little scale back there and we had to weigh every pack, every little bag

P: What years were you there?

E: Now this is uh, in um, well, let’s see, I graduated around, uh ____? I was 14 so um, let’s see, I think it was ’48 or ‘49

P: Let’s go back to when you were a little girl and you were going to school

E: Mhm

P: And you were telling me about, uh, what it was like in the classroom, when the teachers came in what would you do?

E: OK, well, we start school in first grade at six years old, we don’t have kindergarten or anything like that before, so um, my first teacher uh was her name was Frauline Kitler? Not ___? Kitler. And we would have to come in when she came in the room we would have to, uh, greet her by lifting our arms and saying “Heil Hitler” and we would say “Frauline Kitler” and it was always very funny, because we would all laugh because it you know behind ___? We didn’t laugh out loud. She didn’t know that you know, that we thought it was funny that we would say “Heil Hitler, Frauline Kitler” you know (laughter). Anyway, um,

P: Well what did they used to say before? What would the children used to say?

E: They said, well they did say

P: Before Heil Hitler, in the classroom, was it about God?

E: No, I don’t remember that.

P: ___?

E: No, I don’t remember what they would have said before that.

P:___?

E: Oh, children before that, I don’t know what they had to do, I wasn’t there so I don’t know.

P:

E: Well, that we say, we say that even now people say ___? That was the general greeting we didn’t have to say that just started and it became so popular that people said that automatically even if you didn’t believe in God. You would say ___? (laughter) ___? Greet God. It’s a, ___?, it means greet God, greet God. And that’s so popular that nobody really ___? or anything.

P: People on the street?

E: Yes, people say that today to each other, I believe. Maybe not as much, maybe they say hello now, and not hello but “Hallo (?)” You know German?

P: Yeah.

E: But, uh, yeah, that’s how it was.

P: Did you do anything special in birthdays? Or Christmas? Or uh

E: Yes, yes Christmas, big Christmas celebrations, we had our Christmas tree. My parents made a big, uh, big deal about it because that was a special holiday. And, and they would, we didn’t get very many presents during the year and uh, for Christmas my mother would make new doll clothes and my father made a doll bed and, um, we made all kinds of things handmade because they didn’t have any money to buy presents. We were kind of on the poor side. We didn’t know that we were poor. But we thought, now that I think about it we were poor but in ___? We had a very loving family, and like I said they did everything they could for us.

P: ___?

E: My sister was born when I was 4. Her name was ___ (name)?

P: ___(name)?

E: ___ (name)? Yes. And, uh, she had problems, she was a little early and so in Germany at that time people would have ___? come to their house and my sister was very, uh, she had problems, I believe, at that time and they had to take her, my father had to, I don’t know how, but, I guess they had to take her to the hospital. And, uh, because she had problems being born early. And I remember taking, I think I was, I couldn’t have been that old, but maybe it was with my third sister she was in the hospital and, um, she had problems and I had to take sometimes the bottles of mother’s milk to the hospital for my mother. But I was only 8 or 9, 8 years old. And he let me go on the trolley car by myself.

P: Was everything in walking distance?

E: No, no, we had to take the trolley car. We had no car. The trolley car went everywhere.

P: Did you sit with your friend when you went to church, when you were five, on the trolley car?

E: No, no, the church was walking distance. Yeah.

P: So where would you like to go from here? Would you like to talk anymore about your early life or…

E: No, um.

P: What was your father’s name and your mother’s name?

E: My mother’s name was Marianne (sp?), Marianne; my father’s name was Konrad (sp?). And, uh, we only had very few relatives, my, my father had one sister, and my mother’s sisters and brothers had immigrated to the United States, they were living in the United States, uh, three brother, three brothers and one sister. And that was a lucky thing because after the war they would send us care packages.

P: Oh, wow.

E: Yeah, so uh, we were very lucky that way. And that, now I’m going ahead of myself, but uh, that was the reason that I immigrated here after the war.

P: I’m really glad you got to talk about it. And your father was still a good book keeper?

E: Yes, and uh, he was actually, the war started, and uh, I mean the bombings started, in about, uh, I think it was already happening around ’40 or so I don’t know, ’42, I’m not sure exactly when it started, but it was maybe not until ’42 or ’43. My, my second sister was born in ’43 and I remember my mother helped and my father was drafted by that time, so my mother had to get three children down into the basement. This is in an apartment house where about 6 or 8 families lived in that and we had, uh, we had in every basement we had, uh, we made a room where you had pillows, a place for us to sit…

P: A bomb shelter

E: It’s like a bomb shelter, yes. It was supported and there was wooden beams and it was very small and we just all barely fit in there and, uh, the men would, uh, one of the men would check sometimes when you heard the bombing going on they would eventually go upstairs and check whether there were any, because the ___? bombs wouldn’t make any noise, so, they had to check once in a while, go up and see if there was a fire in the building and on each floor of the apartment building there was a bucket of sand, a bucket of water, and then a ___? thing that you could put a fire out with, like a, not a broom but you know there was a flat thing and a ___? thing to hit the fire and put it out. But it was ___ luckily in our building; I don’t think any fire ever started. But there were many fires around us, and one day there was not too far from our house, we could see the building, in the day time of course, there was a factory and those were the things that they started bombing at the, in the very beginning and they knew about where the factories were and the big buildings and they would, so they would bomb those factories and it was the hugest, I mean the biggest fire that I’ve ever seen in my life and they acted the alarm and all, and we all went outside because it was like daylight from that fire where we were standing and the cinders from that fire were flying through the air like snow, they were coming down like cinders. That’s how close that fire was.

P: How did you feel?

E: Well, it was very scary. But of course my mother was there and I think that was when my father was still at home when that happened. And, uh, we lived through it; it was just, as a child…

P: What did they tell you?

E: Well, I remember there was war and I knew that they were bombing us, even as a child. But, we didn’t quite understand why or, you know, and, we, as long as nothing physically was happening to us, it was scary, but we just accepted that it was happening, and as a child you accept everything that comes to you, you know. You learn things and you learn that too.

P: Mhm

E: And they really don’t tell you anything about it. And you have your mother there to comfort you and you just live through it the best you know how. But it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t leave scars, and for instance: the alarms from the fire – from whenever the alarm would go on and later, you know, when they knew that no more bomb – they knew that no more airplanes were around, so they would give us the ___? What do you call that in English, uh, you know when the alarm is over. They had a different sound than the sirens. And that was the when you knew to come out of the basement. Normally, we didn’t go outside. But that day we all went outside to see that fire. And then, well, I guess we went inside and went back to sleep. But, it was really an ordeal for my moth- then when my father was summoned in the war. Then it was a big ordeal for my mother to get all of us ready, uh, to, you know she had two babies by the time in ’43. She had my sister, who was four, and I, by that time, I was about eight. And…

P: Your little sister, what was her name?

E: ___ (name)?

P: ___ (name)?

E: Yeah, and uh, there were three ___? myself. And, and my mother had to get the three of us ready. I had to, in the evening, I had to lay my clothes down exactly how I’m gonna pick them up and put them on in the morning – in the night, because, you wanted to…

P: In case…

E: In case of the alarm. So, so I need, I had to dress by myself. And so, she knew, I knew exactly what to put on, you know. And then she had to dress the four year old, and then pick up the baby and go down the basement.

P: It sounds as though your mother did a very…

E: Oh yeah…

P: …fine job

E: Sometimes, we were the first, we were earlier down in the basement and some of the older people who lived upstairs, you know there wasn’t any other children in that building. I believe it was mostly older people. And sometimes they got down their later than we did.

P: Were you frightened when you went to bed thinking that that was going to happen or…?

E: Well, my mother tried to, uh, no, I mean there was frightening moments but, you know, we took that in stride. We knew already that we’ve been down there before and it was like, almost like, normal by that time, you know?

P: Mhm

E: And, and you just did what you had to do. And I, I usually, I just got dressed really fast and down we went.

P: So the next day and you went to school?

E: Yes, and uh…

P: Did everybody talk about it at school?

E: We walked to school…

P: Did people talk about the children at school?

E: Ah yes, and then, in some cases, I think some people, oh yeah they talked about the bombings around us. And in Nuremburg, the inner city got bombed, I remember my mother talking to other people and they were telling her how bad it was. They didn’t have too much news, you know? They didn’t tell us details. You had to really find it out yourself. I mean, they might mention it on the news, but not in detail. And I remember only once, my mother took me to the city and I remember seeing a bombed out building, and the building was still standing, but the wall was gone and the furniture is still standing in those rooms and it’s like, it’s like a fairy tale. You don’t, you can’t believe it.

P: Well how would you find out then?

E: Well we did find out. I mean, we heard, you knew what was happening when you’re in it. When you’re feeling the bombs, you know? So you know that it’s happening and you, like most, I guess, people were still going through the city and saw all of that, you know. But, since my mom had three children, she couldn’t really take us. But, I do remember that one time going on the trolley car and seeing that stuff. I remember we didn’t go to the city very much or look at that stuff.

P: Were people nice to each other?

E: Oh yes. I think so. And you know once, once they were bombed out they had to find somewhere to live and, uh, then there was already, refugees were coming from other countries. So, Nuremburg was getting really crowded with refugees. Even in school we had all these people from other, um, they were coming from Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, and all those places that they were fleeing from where they were. The Russians were coming or whatever. I don’t know. You know what I’m saying? And I remember those people that had to live in big buildings that had been set up, um, quarters for them to sleep. They only had curtains around them. And then the family had to live just behind the curtain and they had only a couple beds for themselves. That’s about it and maybe bunk beds. They didn’t even have, you know, no more room for things like bunk beds. And, I remember only seeing that once when I went with one of the girls in my class, when, she took me to her- where she lived. You know? And it was amazing because people had to get along like that you know? In living quarters like that. And so, that was happening. And then we couldn’t have school anymore because the bombing was started at, in the daytime. So they decided to evacuate all the school children to the country and to farmers in little villages. Any family who had any room in their house, they had to take in a child. So, I had to go too. And that was by, that was when, towards the end around ’44.

P: So your father was gone?

E: My father was gone. And my mother had to stay for a while in Nuremburg in her apartment. But, while I was gone, for maybe, I forget how long, but 6 months. She also had to leave Nuremburg. By that time, the bombing was so bad that they evacuated any woman with children that they possibly could. They evacuated them to the country. She was sent somewhere else. She couldn’t come where I was.

P: Did she take her two other children with?

E: Yes, yes, yes.

P: Where were you? Can you remember?

E: Well I was in Ezelheim by Suttenheim. A really small village, uh, I can’t, uh, it’s not too far from Wiirzburg. In other words it isn’t that far away from Nuremburg, but my mother could never come and visit because now they were bombing in the day time and they were bombing trains, so she could not unless she came on a train. And with two babies she’s not going to go on a train. So, my aunt, my mother’s only other sister left in Germany, who would not marry ever, she came and visited me once in that place just to see how I was. And I was doing fine. I got to a family that had one child. And actually they were a grandmother and a grandfather living there and then the parents of, and they were the child-, I mean, the children of them which was their son and daughter in law and they had one child – 5 years old who I was able to play with and actually I took care of her. I’m eight and a half, you know, about nine. Yeah, pretty much nine.

P: Now, let me ask you a few questions about the planning of it. Where you were. You were…

E: I was ___?

P: As you were talking about yourself and your lives and then the bombing got worse. And in the day time you couldn’t go to school.

E: Yes.

P: And so how was it presented to you? Your dad, your father was gone I think.

E: Yes.

P: So, how did your mother…

E: The government, I don’t know exactly how my mother heard about it but she had, from the schools I guess.

P: How did she present it to you?

E: Well, I had, you know, she just told me I had to go to this place in the country. And I had ___? because of the bombing going on in the daytime. And I mean, I didn’t want to go because I had one time before been on a, from the school, any children who were a little undernourished, which I was. They’d send doctors to the school and they examined the children in the school and they told them if they needed more food or more, a little perking up ___? Summer vacation, the year before, they actually sent me for six weeks to the country, to a farm. And I did not like it. It was so lonesome! I was the only child with that family. They had no other children, only grown up sons. And it was so lonely. And they wouldn’t let me go play with the other children because they had to watch over me. They didn’t want anything to happen to me. So, that was understandable, but it was really lonely. And I did not like it. I mean the people were nice to me.

P: So you were like six or something.

E: Yeah, six or seven, maybe seven. I was probably seven or eight. Because by the time that I went to the other place I was nine. So, I really cried. When my mother had to leave me on that train I really cried. I did not want to go. But you had to go and my mother had to do it because she couldn’t, she…The school children had to go because they wanted them to go to school. You couldn’t…you know? So she let me go. And we had a one room school house and one teacher.

P: She let you go or she…

E: She had to let me go.

P: OK

E: Yeah, and I had to do it. So, by the time…

P: Now, what kind of woman was she? Was she crying too?

E: Oh yeah. She was crying I’m sure, yeah. Oh yeah, my mother was very loving and very kind. And I mean, what can you do? It would be hard for the Americans here when something would happen like that, I always wonder what they would do because I can’t see all the children going to a country place and to a farm, you know, I can’t see it.

P: When did you wonder about that? About when?

E: Uh, yeah, only sometimes, yeah. And grown up, you know. That thought just came to me sometimes.

P: Yeah, well certainly thank you for that thought…

E: Yeah.

P: For thinking of somebody else.

E: Anyway, so then I’m in that country place and, um, just being integrated in their home and they would, they’re farmers of course. The women had to go; even Grandma and Grandpa had to go to the fields during the summertime. We two children would be left at home sometimes, all by ourselves. We were nine and five. And then especially in the summer when there was no school. Those six weeks.

P: And in the school out there was it still “Heil Hitler”? In the classroom?

E: I don’t remember. I don’t remember doing that. But, it probably, uh, I don’t know. But I suppose it was. Uh, but that’s a good question. I’ve never thought about that. Uh, but there was no ___? Uh [pause] I don’t remember any emphasis put on that, but we had to do anything special for that, you know, except maybe saying “hello”; “Heil Hitler”. And, that wouldn’t really bother us, you know. And uh, but [pause] yeah we were…

P: Well, you were used to it.

E: Yeah, so we, I mean, I wrote letters to my father and mother and they wrote to me. That was the only communication that we had, you know. It was interesting.

P: Did you have your own room? Did you share a room?

E: You know, at first I had a room upstairs. And it was, again, I think I was so lonely and scared alone up there that I told them about it. And they were actually nice enough and made a bed in the living room for me.

P: Wow.

E: Yeah. And in the living room in the little corner there was my bed. And there were other…the young couple and the little girl slept on the, in another little alcove off the living room with a curtain. In other words, there wasn’t really enough room for all of them to…Apparently they didn’t want to be upstairs either [laughter] because they slept in the little alcove and then Grandma and Grandpa had their own room across the floor. And then there was the kitchen. And, uh, that was it. I mean it was a fairly large house. But, they had about two or three bedrooms upstairs, but they didn’t use them.

P: It sounds like it was as good as it could be.

E: Yes. And the upstairs I know they had full of furniture that was…they put that in from their other son who lived in another city. And, they didn’t want to lose everything so they brought that here for them to save it. So it wouldn’t be bombed out. And they also had another daughter-in-law who came after a while, after I was there already a while when she had to come from another city with a baby. And because her husband was in the war too. And so, I remember, um, so we lived there for that time. And we, we would see, sometimes we would hear the bombing from Baumberg, we could hear the bombings.

P: From where?

E: I think it was Baumberg.

P: Baumberg?

E: Yeah, Baumberg. And the sky would be all lit up. I remember seeing it from the bombings. So, it wasn’t that far away, but uh.

P: So you couldn’t really get away from it completely.

E: No, but we didn’t really have any fear that we would be bombed because they didn’t bomb the little villages, you know.

P: So, how did you know that you could go home again?

E: So the first, um, well first came…the war was coming to an end and, um, we knew that the occupation was taking place. And that it was, that they were coming from village to village and town to town.

P: The Russians.

E: Not the Russians, the Americans. And I was definitely in the American area. We knew that. And so, so one…the farmers had prepared for all, for this day to take place. In other words that had arranged for places outside the village where we could go in case there would be some fighting going on in the villages. Because in some villages there were still German soldiers that would be coming, uh, defending the town. In our village we didn’t know, because they, we didn’t know if there would be any showing up. There were none there, but we never knew if they would all of a sudden show up and defend this town. So, what happened was, we knew that soon the occupation would take place and we had heard in other villages there was fighting going on and bad things happening. Not that they let me know that right away, I had no idea ahead of time. But, I found this out afterwards, you know. So here we were, that day, awaiting for this occupation to take place. But, we decided that on this morning there would be, the ___? planes were flying over already, occasionally, and um, so we decided to leave our house because we…

Tape 1 - Side 2

E: So we had heard about the occupation taking place very soon by a messenger coming on bicycle letting us know what was going on in other towns near us. So, we figured out that it would be taking place in the next three hours. It was an early spring morning in April. And we all decided…they had already arranged…All I know is that the Grandpa was in charge of me because we couldn’t walk anymore than two or three people because we didn’t want groups of people going somewhere because they would be afraid that they would shoot us or do something to us. And so, we only walked Grandpa and myself, and he had the baby in the baby carriage. The daughter-in-law that had come from the other town with her baby, well he was in charge of the baby carriage with the baby in it. And we walked through the country side, just for a short distance, and then we had to get out, into the, it was between the fields, you know. And the end of the village there we walked ___? And it had rained a lot, you know, springtime. So the road was muddy and all of a sudden we came to a, I don’t really know where we were going, but, they didn’t tell me I just followed, and uh, so um, then we came to a place where it was really muddy and he couldn’t get the baby carriage through the mud. So, he had to leave the baby carriage there, picked up the baby, and we’re walking a little further trying to find the place where we were going, which I soon will describe. But, on the way, one of these low flying reconnaissance planes came. We could practically see them sitting in the plane, that’s how low he was. And he saw us of course. And guess what? About – how many feet from here to the chair? – Uh, I don’t know three yards from us. He shot down, he was shooting down, and I’m going to make the noise [makes machine gun noise] [laughter] so, he’s shooting down. And it looks like they’re shooting at us, I mean, we don’t know, we’re just scared to death. And we jump down in the side of the road…

P: A trench?

E: In a trench, yeah, but he had already gone by and then he flew away. And he came by one more time, but he didn’t shoot the second time.

P: He probably saw who you were…

E: He probably was just scaring us, you know? Because he could have shot us.

P: Sure

E: I mean ___?

P: And these were Americans?

E: Yes, Americans. So, anyway, he was probably saying, “what the heck are you walking out there for?” [laughter]

P: What were you thinking?

E: Well, oh we were scared to death! Yeah, the Grandpa and me both were just scared to death.

P: Let me interrupt you for a minute. When you were told to do this and to do that, who was that? The police?

E: No, no, no police. It was…

P: Or soldiers?

E: No, no soldiers in our village, nothing. The people getting the message from themselves. I think they were doing whatever…

P: No, no, no I mean like: don’t walk over here, do this…You were sort of getting instructions…

E: We knew where we were going, but I didn’t know because I’m a child, nine years old. So, here, I’ll go nine and a half, here we were, we didn’t, they must have had communication between the leaders of the towns, you know?

P: So people helping people.

E: Yes, and the soldiers I’m sure didn’t…maybe the government, maybe somebody had told us that we had to make a place outside of the village so we could go there in case there was something going on. I’m sure the government agreed that we should go to a safe place, you know? [Pause] So, we get there, it’s like a hallway; in other words, when you walk down a little bit into the ground almost, and on one side, both sides actually. But, on one side there was a higher, the ground was high and the road went down and they had actually prepared this, uh, the high side of this wall, they had dug out so we could actually stand inside but it was open to the air, you know. But, just so you couldn’t see us from the air practically. So, we stood under there, in that little walk way. And we were just waiting because the planes were flying over and we knew the occupation was supposed to take place but we didn’t know which side of the village they would be coming in from. But it was actually, we were at the, uh, whatever side of the village, and there was a road going straight across and we could see it from where we were now in this hole. We were not far away. And there was, all of a sudden we heard the tanks coming, and they were actually rolling, and so the people in our little place, there were more than us, you know, we were about maybe 15 people or so in this little area. And, they would go out with a white flag and they waved the white flag, I mean a white towel or whatever. And, um, to let them know that we were giving up, you know. And uh, we were not fighting. So, then of course we stood there for a long time because these things were rolling into the village. And we were listening whether there was any fighting, but we couldn’t hear anything. And after about, I don’t know, three hours, somebody came from the village and let us know that we could come back in. And, um, I guess this, they had people arranged that were going to be there ahead of time. But, I mean it was amazing how they did all that. And then when we walked into the village, you know it’s only a little dirt road, and our house was actually the first house on this side, on the right side, and uh there was first the cemetery and then our house, and our barn and then, uh well, the tanks took up the whole, width up the road. And we could barely get into our gate to our house. And so, we planned in there and uh the other…

P: Were you afraid of the tanks? Were they scary?

E: No, not really afraid, but it was scary yes, because you know I guess the soldiers were walking around and we were scared of them. We couldn’t talk to them, they couldn’t talk to us. So it was very, yeah it was very scary. But we went to our house, and everybody else went to other places. They split up those families to go to different places so that if one family got bombed or shot – all the family would be dead or something.

P: Or hurt.

E: Yes, that’s why we were in this place and our ___? family, I don’t even know where they were. I never found that out.

P: That’s interesting.

E: Yeah, And then, so then we were in the house. So the soldiers let us go into the living room on the first floor. And um, they by sign language ___? the wall I guess, you know. We were sitting in the room, all of us. And they told us by sign language, because we wanted to lock the door. And they said “no, no, no, no” we couldn’t lock the door. But, they showed us why. And that is how they demonstrated by one soldier walking up in front of the house; he walked back and forth with his gun. In other words he was going to guard, they were guarding the house and, uh, we didn’t have to lock the door. And so, they showed us by leaning their head over into their hands that we should go to sleep. And uh, so it was night time and we uh, I don’t know if we ate anything, I cannot remember that. But we must have eaten something. And then uh…

P: There must have been some of a relief that they were showing you to go to sleep…

E: Yeah, that’s true. That is beautiful, but wait till you hear what comes after. [laughter]

P: Oh my, you’re a very good story teller. I thank you for that.

E: You’re welcome. Well anyway, so here we are. We didn’t go to sleep. Only the five year old went to sleep. She fell asleep. But, I was sitting up with all the grownups. I had, I all dressed in my clothes. None of us got undressed to go to sleep. But we turned the lights off and we were in the dark, so they should think we were asleep, and we were watching everything out the window and then, uh, I had three little satchels in my hand that I was supposed to take if anything happened we had to go somewhere, we had our most important clothes or something, I had three little satchels. That’s all I remember. And, um, so now we’re sitting there waiting and not knowing what to do. And, uh, all of a sudden we heard, I don’t know how long that took, before we heard some noises outside and people walking. So, we opened the window and asked them what’s the matter and why are they walking. And then they told us. They said that in their house things were not so good, that they were all getting drunk, the American soldiers were drinking and it was terrible. They couldn’t stay there because they were trying to, uh, take the young girls away and you know, do what with them. And so they left the house and they were going to another place where they knew we could go if there was anything wrong and that was the wine cellar or beer cellar, whatever you want to call it, from the restaurant. In other words it was underground and that’s where they were going. They were scaring us so badly that we left our safe house that we could have slept in if we wanted to and went and followed those people to go to that wine cellar. And when we got there, uh, everything, well we stood, we were stand, it’s not very big so there was just room enough for us to stand in there in the dark, it was very dark, the only thing they had as a light was a hand held lantern. And Grandma, oh yeah by this time Grandma was in charge of me, and uh, of course the young lady had her baby and the other woman with – had her five year old. But the men didn’t go with us to the wine cellar. They went somewhere else. And I only know that we found out later, well, I don’t, no they did go there with us, but wait a minute I’m getting ahead of myself. They did go there with us, but, so now we are in this wine cellar, and uh, it’s really dark in there and all of a sudden the young woman with the baby must have been a little further in the back and she called to Grandma to come and get her baby. And the reason was, oh well it must have been, oh I know what happened first. So now there is some commotion and, and we want to get back out of some ___? and they don’t let us out. So things, the guy that’s holding the lantern, uh, some guy is holding the lantern and another guy is doing something to the lantern. The lantern goes out. And then he shot his gun in the air, into that ceiling of that basement, of that cellar which is stone. And so the stone ___? were flying. And well, first of all, Grandma left me standing there, said “I’ll be right back” because the girl had called her to her to get her baby. And I’m standing alone by the door and she gave me her purse too because she knew she was going to get the baby and she says, “I’ll be right back”. Well, uh, in the mean time the lantern goes out and the guy shoots in the air, and so I’m standing at the bottom of those stairs and the woman next to me is crying because something hit her, I guess those shrapnels or whatever from the ceiling hit her. So now they’re all trying, because we’re just panicking, everybody’s screaming, and so they want to get out but they won’t let us out right away. And finally, I found that out later, the school teacher actually, got himself through the barricade up there to let everybody out. But they hit him, they hit him with a gun, they didn’t shoot him, but they hit him with a gun so hard that his leg broke and then they took him away in a jeep, well they took him away to the doctor, to a whatever, I don’t know where. And uh, then we learned all that the next day. And in the mean time I’m still standing there, now the people are going up the stairs, and now I don’t know what to do in the dark because I can’t see Grandma. She told me to stay there, but I didn’t, I started walking up the stairs with the rest of the people. So now I feel, in the dark, on the stairs I feel a fur coat in front of me and nobody in that village had a fur coat except for the young lady that had the baby. ___? from my house. So I grabbed onto her fur coat because I knew who she was because I didn’t know all of these other people. And I followed them up the stairs, but until I got up there I realized that two soldiers were dragging her up there. And so I let go of her fur coat, I didn’t go with her, because they dragged her over into the, underneath the trees, and I couldn’t, I know they laid her down or something, I’m only nine years old. I don’t know what they were doing to her.

P: Was she making any noise?

E: I don’t know, I don’t know if she’s making noise or not. But can she do noises who’s going to help her? I don’t think she was making noise.

P: But I mean was she crying?

E: Yeah crying, she could have been crying. But by that time I had let go of her, but she was cry – I only looked where they went and then I didn’t follow. So then I’m looking for Grandma or somebody that I could find, well I hear a baby crying and not the baby but the five year olds voice I recognize. So, then I saw them – her mother and her – so I latched onto her and went with them. And she was being told by another lady that in her house there were no soldiers; that they had left a note that they were coming back later but there was no soldiers directly in the house at the moment. So she decided – we decided to go with her instead of going to our own house again which would have probably, not probably, but we would have been very safe. Well we go with her to this house, and uh, we were safe there. Except all night we sat in the dark on a bed next to each other in a dark room because we were afraid of, you know soldiers would come in or whatever. And so that lady told, I mean even at nine years old I heard everything that they said, but these people could not help but telling these things even so, you know, that I should not hear it. But anyway, that their daughter, they hid their, they hid their daughter underneath the drop of the animals in there, in the barn because you know she was a younger women and that’s who things were happening to, you know. And so anyway that was that. And then all night we sat there and all of a sudden I, there was sometimes we could see a soldier with a flashlight walking by, we did have a window to look out to, anyway and then I all of a sudden realized I wanted to – that I was shaking – and I wanted to stop shaking and my body was just trembling like this and I couldn’t stop shaking. I thought it must have just started when I realized that I was shaking and then I couldn’t stop shaking; I was in shock. And of course as a child I don’t know what’s happening to me, but I didn’t cry I just sat there with the woman – with the women – and shaking away and then it, and I never slept one wink [pause] all night. And then the dawn was coming and we decided that maybe we should, nothing happened, you know no shooting or nothing, and we decided that maybe we should go to our house now, you know. So we started walking and nothing happened to us, It was sort of dark yet but we saw some soldiers but they let us walk and we didn’t have far to go to our house. We got there, Grandma and Grandpa, Grandma was there and Grandpa. They had been in a, Grandpa and the son had been hiding all night because they were afraid, ‘cause they were – the soldiers were afraid of the men and the men were afraid of the soldiers more than the women, you know. You know what I mean? So, anyway, they had hid in a vacant bee hive outside of that thing. So they, uh, anyway they were there and the young women was there with her baby and Grandma. Grandma walked right from that thing with the baby to her house…

P: Oh.

E: In the middle of the night and the girl…

P: She forgot about you?

E: No, she had to, I wasn’t there anymore standing, what can she do?

P: Was she surprised to see you?

E: But yeah, I’m sure, but I can’t remember we didn’t talk about that much. We just were glad we were all there again. And then, but then I heard the story what happened to the young women you know. She got, she was raped and then she got away and um, she ran away and they shot after her but they didn’t hit her. She got into the back of our house because our house was the first house from where that cellar was, too. And, uh, and she ran into the barn and she climbed up in the barn and hid up in the hay. And, uh, they ran after her but they couldn’t hear or find her, and then they left. And, uh, so then she, after awhile she slowly went back down and got out the front, which, which was – she got in the back and then she went out the front which is where the house was. She had access to the house and that’s how she reunited with her baby and Grandma.

P: Wow

E: Yeah

P: That was quite a story and you must – you were really brave.

E: Yeah, we learned to be brave I guess. In the real life, you know, what, uh, all you can do you don’t know. I had, uh, I had done a lot of things during that time I was in that village. Which, I mean I took care of that little girl. I set the animals sometimes in the summertime, like I told you earlier. Anyway, um, I don’t want to go backwards, so…

P: Does it seem like a dream?

E: It does sometimes, yeah. And I realized only years later that I had post traumatic syndrome, you know; um, especially when I would hear a siren. If I heard a siren, even now it upsets me, but because I told this story it got better each time. Each time I would tell – now I’m not, I’m not as excited – I’m excited telling the story but I don’t get the real, um…

P: Complications?

E: Yes, uh, like the excitement that I would be really upset, you know. Because one time I realized, the time I realized that I had post, uh, post, whatever, syndrome was when I went into a wine cellar here and I actually got that same feeling like I, you know. That’s the reas – and you know in those days they didn’t know what post traumatic syndrome was, so I learned it quite a lot later. Yeah.

P: So, you were reunited with…

E: With the whole family yeah.

P: With the whole family?

E: And everything from then on, it was not too long later; I forget how long I was there, probably still. They had a date, there was a date set when you had to be back in Nuremberg because they had so many refugees and so many people that needed to, you know like people that didn’t have homes anymore. So, they set a date and after that date you could not go into Nuremberg anymore, so… You had to be in there at a certain date. So, my mother had to be back there and I. So my aunt came to pick me up, and uh, took me home. And this aunt that was single, she lived in the house in the, in the garden stop – Garden City – where her parents and my, well where her parents had lived. This Garden City was quite remarkable. It was all one family homes that had been built after the First World War for the working class people. And it was at a reduced rent, you know. And they all had one family homes with a garden in the front and a garden in back. And now, now everybody had to take in strangers. If you had any room in your house you had to take in somebody…if you still had your home because there were so many homeless people. And so, but I don’t think anybody slept ever on the, in the outside. They all either got into homes or big buildings like, like, uh, any kind of rail road station or any kind of place, they set up places for people – refugees that had to have a place to live.

P: So where are we now? As far as 1940…

E: five.

P: So…

E: So my mother and, and, got back into the apartment. But, so now, it took a little bit, it must have been a little few months later, when they decided instead of having us take in another, my father by the way came home not long after that. He had been a prisoner of war in Italy in the American sector. And so, when he came back we were still in that apartment, and then after a while we decided instead of taking in a stranger or strangers my aunt again, in that garden, in that other house, she had already taken in a family of four. And, um, so, we decided that we would give up our apartment to this family of four and we would move in with my aunt. So she didn’t have a stranger and then they didn’t have to live with strangers and they had their own apartment. They of course liked that, you know.

P: How was your father?

E: My father was fine. He got shot in his eye. But he didn’t lose his eye, I don’t know, during the war. But that’s all that happened to him, he was fine.

P: Being a prisoner of war ___?

E: Yeah, he got along very well in the prisoner of war camp because he spoke English ___? You know, he had gone to higher school and had learned English when he went to school. And uh, so he, so the American soldiers treated him very well. He got cigarettes from them and um food sometimes I guess extra and they took…yeah they were very nice.

P: So what did the Germans losing the war mean to you?

E: Uh

P: And your family?

E: I don’t know. It’s like as a child of course I only later would have had an opinion about that. Now, my father and mother, they just were, uh, they accepted everything the way it was because that’s all you could do. You had no choice.

P: Must have been glad it was over.

E: Yes, they were just glad that we were still alive and that we didn’t get bombed out and hurt. And my father came back from the war; in other words we were lucky, we were a lot luckier than a lot of other people. And on top of that after the war we were really lucky because we had three relatives in the United States who sent us all kinds of care packages.

P: I was just going to ask you, and you mentioned that before, but I was just going to ask you if you would talk about the food even when it all started you said that…

E: There was rationing, yes. And we really didn’t have much food, except that my, we were lucky too that my mother had a baby, so ___?, and a younger child. The more children and the younger children you had you got more rationing for milk and maybe cereal and things like that. So, we were lucky that way that we had actually a little more access to that kind of food because the grownups didn’t get all that, you know? Uh, when they had no children, I’m sure they got a lot less.

P: And on the farm you probably ___?

E: On the farm I was very lucky because I got, you know, good food yes. And they bake their own bread and they had all these, yes.

P: Did you ever see those people again?

E: You know what, we didn’t go back right away, but after I had already gone to America my cousin lived in ___? not far from there. And one year I was visiting my cousin and he said, “Inge would you like to, what would you, where would you like to go?” And I said, “You know what, I really would like to see that village in ___? and visit those people.” And that wasn’t until a lot later. I mean like, in, I’m sure it was like in the ‘80s or somewhere in there. And I actually now am in contact with that five year old girl, who’s of course not five years old anymore [laughter]. And uh, yes we call each other on our birthdays…

P: Oh, that’s nice.

E: And I have gone over there, visited her two times, but that’s it. I, and now I don’t know how many more times I will go over there to visit. But, when I do go I will see her, yes.

P: Um, back to the food, we got up to it and then I think I changed the subject on you, but what was the, um, what was it for you when you came back from the farm and you were all together again? Grateful for what was happening?

E: Yes, grateful that my, one aunt sent care packages that were left overs from the American army. You know, that you could buy those rations packages. And, we used all of that, let me tell you. Even some of it was not so good tasting as you know how dry egg yolks are, you know, dried eggs. It wasn’t like real eggs, but we used all of it. And my mother used it in baking and we were, yes. But you know, other people had a lot less and I think my mother gave away some of it to our neighbors, and maybe, and my aunt that, you know.

P: You were, two or three times talking about you were lucky, you were luckier than other people.

E: Yes.

P: Was that something that you yourself realized? Or was that something that you heard your mother and father telling you that “we are really luckier than most.”?

E: No, I think that at the time my mother didn’t really mention it because, you know we tried not, to children you don’t mention it that much or whatever, but later on this is my, I came to the conclusion that I realized how lucky we were, yeah. That came to me later.

P: So what do you want to talk about now?

E: Well…

P: Well you were ten years old then, right?

E: Yes.

P: And your father was there and your mother was there

E: Yes.

P: And your sisters and…

E: And, oh I want to mention a little bit about what happened after that, we learned for instance that my, you know, friends didn’t really communicate a whole lot during this bad time because they couldn’t get together anymore, there was no way. And most of them were put out into the country side. And when they all came back we learned for instance that my father’s best friend had been put in a concentration camp and he was not Jewish. He helped Jewish people stay in his apartment and let them sleep a couple of nights or a night; I don’t know exactly what their story was. But, he was turned in by somebody in his apartment house. So he snuck them…

P: Do you know what camp it was?

E: No, I do not…Auschwitz probably, but I’m not sure. But he came back. In other words, apparently they, they, the thing is that I want to mention that people at that time, not even him could tell what he went through in the concentration camp, what he lived through. He never even told my father, his best friend, not his whole life because he was still afraid. Because you see, people couldn’t talk about anything about that. During the war and after the war they never talked about it because they were still afraid that somebody would do something to them.

P: You mentioned, and I don’t think we have a tape on, at that time we were just talking before we started, about the fact that your mother and father and nobody really talked about anything.

E: Yeah, and during. And when I first came here I remember people asked me questions…[

Tape 2 - Side 1

P: Now, we were talking about, um, just in the beginning of the war, your parents and your friends did not speak to each other about what was going on. I’m not talking about the camps, I’m just talking about when Hitler was rising…

E: What he was doing, yes.

P: What he was doing.

E: I mean they, I remember my father listening to the radio of course. And I remember Hitler’s voice on the radio because, you know you had, it’s anybody that lives in any place, they would like to know what’s going on in their, politically in their country, right? So, of course the little bit that they let us hear or see or whatever, you know, my father listened to it. But he was not involved in any political party that I know, I know for sure. But, all I know is that there were many people who I’m sure saw some of the good things that Hitler did and that’s the reason why he was, got in actually, because he promised, like any politician would, all these good things that he was going to do. I mean he promised them a car, he promised them, you know, the Volkswagen, that was the car, and of course he did do a lot of building of the railroads and the autobahn, you know. And so, he gave people a lot of work. I mean, he, there was…

P: the depression.

E: After the depression, yes.

P: But, you indicated that people were afraid to talk politically because they didn’t know who would turn them in.

E: In or not. That’s exactly right. You couldn’t talk about it. You could not talk about it. Yeah. And, um, so I [pause] and I really don’t know how much people knew because I’ve, like so many of us, when we’re young, we forget to ask our parents those questions [laughter] and so, I am very sorry that I don’t know, that I didn’t ask my mother more questions about that.

P: Well, she might not have been able to answer the right way.

E: Yes, that is true.

P: So, so you came to America.

E: Yes, so then it was only about eight years after the war was over. My uncle came to visit us from, one of our uncle, my uncle came to visit us, and I ask him immediately because everybody at that time was immigrating and it took, um, it took two years before you could get your visa. So I ask my uncle, when he came, whether I, and I was about 16 years old, and he said, well he would sponsor me, but not until I was 18 or finished with, you know, my training and all that and my work. So, but since I wanted to come and I knew it was two years it took I put in for my visa at 16.

P: And who helped you make those decisions?

E: I just knew that I wanted to go to a better place than where I was. Everything was kind of uncertain, you couldn’t get a job very easily and housing was very scarce and so, it was just my decision. I know some people can do that and others can’t. Like, I had a girlfriend who asked me, “How can you leave Germany and go to America?” and I said, “I don’t know, I just want to go.”

P: So, OK, you came from Germany and you had a very difficult childhood with your parents doing the best that they could under the circumstances.

E: Yeah.

P: But it was quite the fragmented and difficult…

E: But you know what we didn’t know that, none of us felt like we were poor or anything.

P: No, no, it wasn’t the poorness of it. It was just the separation…

E: Yeah, then what we went through.

P: The lack of food and, and, just the daily, daily things that your parents tried to shield you from…

E: That’s true.

P: But, it was still happening. So, um, I’m sure they did the best that they possibly could. But, it does, I was wondering what affect it had on you and if it had an affect it would, uh…

E: Well it made…

P: For raising your own children.

E: Well, all I can say is that it made me a more frugal person. It shaped me into who I am. I don’t think you ever lose anything when you go through hard times, I think you gain…[pause]

P: And who are you? [pause] Well, you said it shaped you into who you are, who are you?

E: Well, who am I? Well, I hope I’m a good person and, uh, a loving person. And I hope that I lived my life as best as I could or knew how and it just, you got this on?

P: Mhm

E: Oh no. [laughter]

P: Yes, it is on. Yes, this is ok.

E: Yeah, this is alright.

P: I want to ask you. You are all those things. Um, for some reason, uh, you have a friend who asks you to speak in front of schools, but you also, uh, requested this interview for the Holocaust Museum and Learning Center. So, I wanted to know, what did you, what did you want to gain? What did you want to be? And how did you happen to want to do that? We’re very grateful to you.

E: Uh, I wanted people to know that the German people went through a lot of hardship without really asking for it. I mean, they didn’t really, I don’t think that most German people wanted to have that, a war. I mean it’s like anybody. Nobody in this, on this earth would like to have a war like that go on. And, so you know, we really, really don’t know. We live life every day but we don’t really know what’s going to happen. But, we make the best of it. That’s all.

P: You were a child.

E: Yes.

P: So you basically had no idea what was happening.

E: No.

P: To the Jews in Germany. Um, may I ask you, what, how was it for you when you realized what your country had done and what the people had allowed it to happen, and you had nothing, nothing, nor your parents, to do with it.

E: Oh, I think it’s a horrible thing, what happened. And what they did. Uh, I, it’s just like any of those; there are still people on this earth now who are doing the same thing practically.

P: Mhm, but let’s just stick to this.

E: Yes, and I think it was a terrible thing that Hitler and all the people that agreed with him. But I think it’s a mass, um, thing that happens when people are pulled into something that they don’t, that, you know, that mass mentality takes over and nobody realized what happ-what’s going to happen out of it.

P: What was it, how was it for you when you began to see the pictures, know, I mean…how did it happen for you? And I don’t want to put you on the spot but I, it’s…

E: All I know is that I slowly learned what really happened only after I even left Germany. Nobody talked about it over there even after the war in those eight years that I was there. Nobody, ever said a word to me about it. Nobody. Because they all still were in denial and they didn’t really want to know about it. They didn’t really want to say…Nobody actually talked about it. That I cannot…That’s the only thing that I can say. And even when I came here and started hearing people tell me things and I was reading about things; I couldn’t believe that this happened.

P: You came in 1953?

E: Yes.

P: What month?

E: In May. And, so it’s very hard, uh, to fathom that human beings can do things like that.

[pause]

P: OK.

E: I’m sure we all know that.

P: Well alright, let’s see, do you have anything else you feel strongly about that you might want to talk about or tell about?

[pause]

E: Well, um,

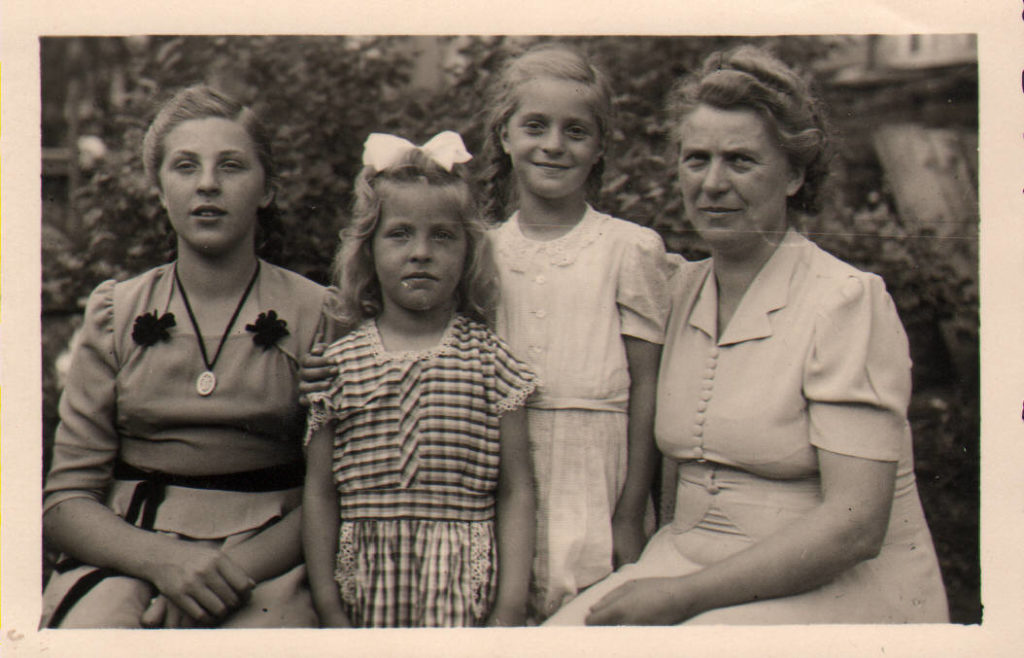

P: If you don’t know, when you get your photograph from your sister…

E: Yeah.

P: We can think of things

E: Yeah, I can add it on.

P: We can add on to it

E: OK.

P: I just want to thank you for suggesting that we do this and I hope I, I think that it got to be hard. I hope you don’t have any concerns or anything about sleeping tonight.

[Laughter]

E: No

P: You said a lot of …

E: I know.

P: Things that…

E: Right.

P: And I, you know, you sit here and I get to know you a little bit and I will go home and think, “What an amazing journey you’ve had and that it’s not easy.” You know?

E: Yeah, well, it, uh, like I said before taught me a lot, it taught me life is ever changing and um, and life is still good.

P: Mhm. Well you’re a lovely woman. Thank you so much. I appreciate your time.

E: You’re welcome.