PRINCE: My name is “Sister” Prince and I’m interviewing Jerry Koenig on Tuesday, November 5, 1985 for the Oral History Project of the St. Louis Center for Holocaust Studies. Jerry, we talked about your name and you said that it wasn’t really Jerry, and tell me about that please.

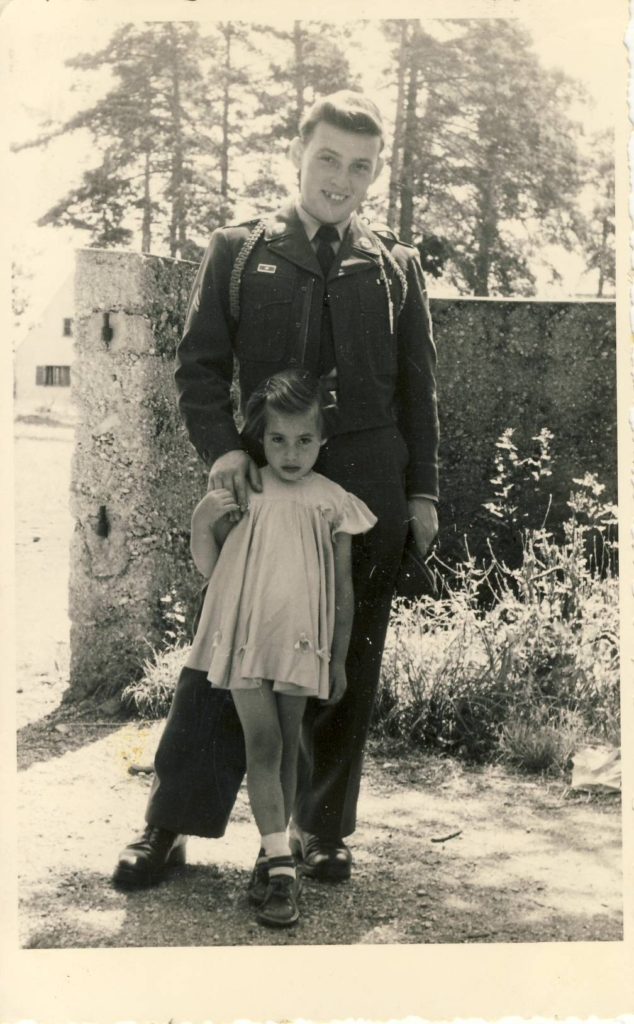

KOENIG: Well, my name in Poland was spelled J E R Z Y, and pronounced Yezy, which, uh, you probably heard not too long ago because Jerzy ______ was the Polish priest that got into trouble with the Polish government not too long ago. And that’s the way to spell it, and that’s the way it’s pronounced. But, when we came to the United States, one of the clerks decided that my name was misspelled and somebody stuck a “z” in place of an “r” and changed it. So when I landed I became Jerry. And then friends of ours in Davenport, Iowa, which was the community in Davenport, Iowa sponsored us, and that’s how we came to the United States. One of the families, they took us in, advised me to leave it alone, changing it, because we felt that that way it would be easier to prounounce it and easier to spell it for people. And we just left it that way.

PRINCE: And it was okay with you?

KOENIG: It was fine with me.

PRINCE: All right. (TAPE STOPS) Jerry, let’s go back to Poland. You were born in…

KOENIG: I was born in Pruszkow, which is a small town, a suburb of Warsaw. I was born January 1, 1930, and (PAUSE) the first nine years were fine. I had a very normal childhood. My parents were very well-off, for Polish standards, and we didn’t lack for anything. Dad was a businessman and we were doing very well; life was good. And of course, in 1939, September 1, 1939, things changed very quickly, very rapidly. And –

PRINCE: By that you mean Germany invaded Poland.

KOENIG: That is right. This is when the war broke out, and things took a turn for the worse.

PRINCE: When you say the war broke out, how did that – how did that at first affect you? What did you – your life was the same up until then?

KOENIG: Uh, yes. Life was the same until then; however, I remember as a youngster – I was just nine years old – I recall that there was an awful lot of talk about the possibility of war. Everybody was preparing; the population of Poland was very busy digging ditches to protect themselves from air raids. And one of the things that many people were doing was pasting up the windows. You would mix flour and water and make a paste and cut newspapers into strips and paste it across the windows in the shape of an “x” to prevent the glass from breaking in the case of an air raid. And I remember very distinctly that a neighbor girl and myself were very busy doing just that. And this is when the first bombs fell on our small town of Pruszkow, which was a suburb of Warsaw. At that time I couldn’t quite understand why they wanted to bomb our little town because after all it was probably a mistake, they meant to drop the bombs on Warsaw, but it wasn’t so because Pruszkow had a – a considerable amount of industry. And there was a plant that produced parts, I believe, for airplanes or something – had something to do with…the war effort. So apparently they were pretty well advised as to what their targets should be.

PRINCE: Did you notice any of your work, uh, any work did it…

KOENIG: It worked.

PRINCE: It did work. (LAUGHTER)

KOENIG: It worked. That’s right. (LAUGHTER BY BOTH)

PRINCE: …I’m surprised. What business was your father in?

KOENIG: (PAUSE) Well, dad managed a lot of property that his dad, at one time owned, and then as grandpa got older, he said, let’s turn it over to my dad to manage for him. And there were apartment buildings, and one of the major sources of income was a slaughterhouse which I guess here you would call a packinghouse. And, in Poland that was a very profitable type of business to be in because it was government controlled and it was illegal for anybody, for anybody to slaughter cattle on their own. They had to bring it to a packinghouse, which of course dad had to provide the facilities for these people and in turn, of course, they paid a fee for the use of these facilities. So, dad kept pretty busy just managing those few pieces of property. And of course I shouldn’t –

PRINCE: What, was, go ahead.

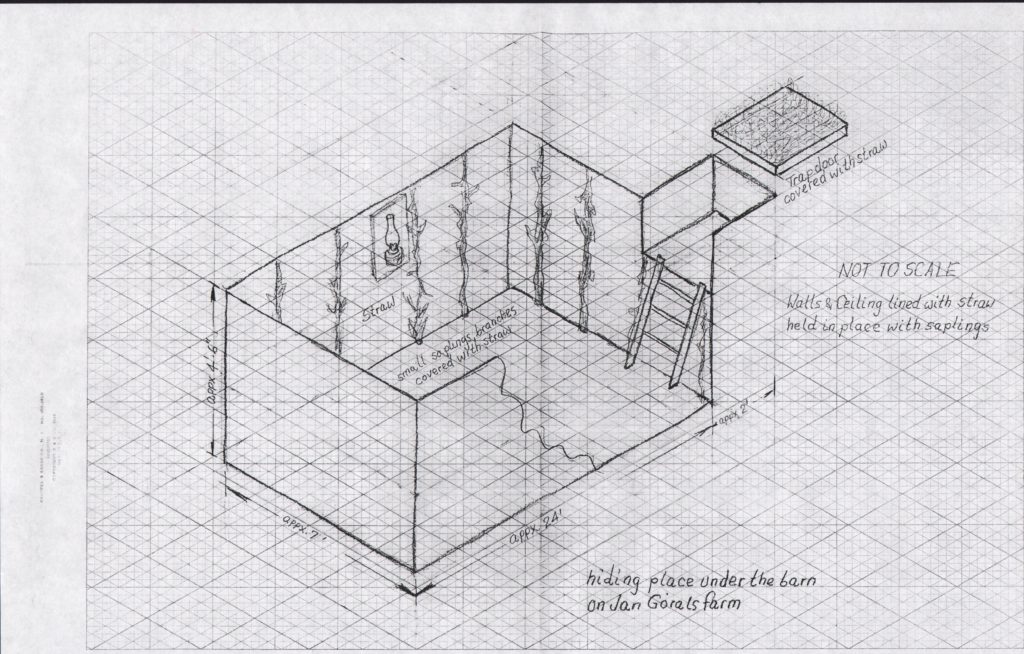

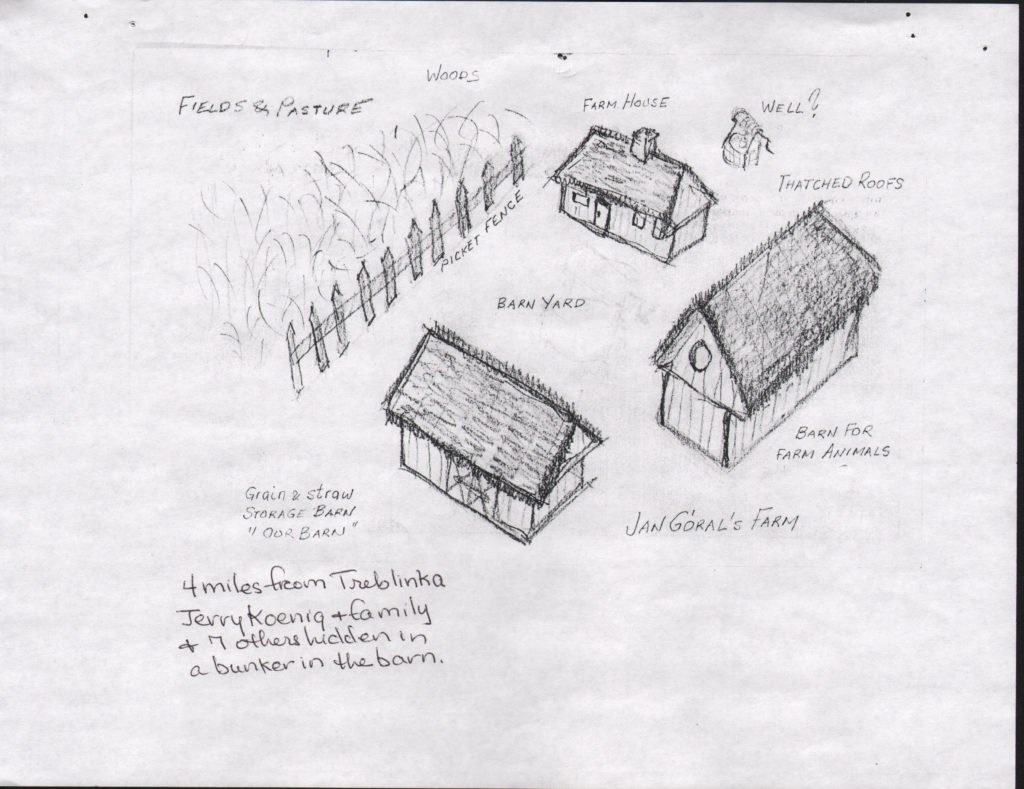

KOENIG: I shouldn’t forget to mention that one of the, probably most important pieces of property that he had, which really wasn’t very profitable, but in the long run became very important because it saved our lives, was I guess, about a 60 or 70 acre farm that dad had in eastern Poland, which we primarily used as a summer vacation. During the year he had a manager for it that was responsible for…managing the farm. And for us it was just a place to go in the summertime, to spend a nice vacation. But later on it turned out to be a very valuable piece of property.

PRINCE: Shall we hold it for a minute, and stay where we are?

KOENIG: Right.

PRINCE: Okay, the packinghouse, was it kosher?

KOENIG: No.

PRINCE: No…

KOENIG: There was a kosher section. In other words, yes, there were facilities provided for kosher slaughter, absolutely, which were not used by anybody else. In other words, they were strictly for the, for the rabbi to perform his job.

PRINCE: Tell me about your family.

KOENIG: Okay, my immediate family was my dad, my mother –

PRINCE: What were their names?

KOENIG: His name was Isadore, her name was Mary. I had a brother, or I have a brother –

PRINCE: Excuse me. Excuse me, did they – was it called – was she called Mary, just like Mary, in Poland?

KOENIG: Yes. As a matter of fact they had called her Marysia –

PRINCE: Marysia –

KOENIG: – which is, which is Mary – Marya is the Polish name, Marysia is – how would you say it… a… a gentle way.

PRINCE: Gentle, touching.

KOENIG: Touching way of saying Marya.

PRINCE: A loving way.

KOENIG: Yeah, right, touching…

PRINCE: Right, then you have –

KOENIG: Then I had a brother.

PRINCE: – had a brother. May I ask why you said had?

KOENIG: Why I said I had a brother? I don’t know, (LAUGHTER) it was a mistake. (OVERTALK)

PRINCE: You had one then, and you have one now. (LAUGHTER) Okay, so just two boys.

KOENIG: Two boys, right. Then of course, uh…

PRINCE: And his name?

KOENIG: His name is Michael.

PRINCE: Michael.

KOENIG: In Poland his name was Michael, which is spelled the same, for example, as it is in English. It’s just pronounced different.

PRINCE: Okay.

KOENIG: But, uh, Michael at the present time lives in Israel. He’s lived there for the past 13 years.

PRINCE: And he’s older?

KOENIG: Michael is younger.

PRINCE: Michael is younger.

KOENIG: Almost three years younger.

PRINCE: Okay, all right, what kind of schooling did you have?

KOENIG: Well, actually – (OVERTALK) up to the war, I mean ’til the war started, or in general…

PRINCE: Tell them –

KOENIG: – ’til the war started?

PRINCE: Tell, just give me, just describe your life in any way you’d like.

KOENIG: Well, it was a public school, a normal grade school in Poland. In addition to –

PRINCE: This was with Gentiles, with non-Jews?

KOENIG: Right, right. Of course, that wasn’t the easiest thing to do, to go to school with non-Jewish kids because in Poland there was an awful lot of, what is, anti-Semitism was just rampant. It’s almost unbelievable how ingrained anti-Semitism is, or at least was at that time, I can’t say how it is now. From what I hear, and from what I read, I believe that really the situation today isn’t any better than it was then. But, at that time at least, it was very rampant, and very much felt by the Jewish kids who went to the public schools. So, anyway, I attended the public school, and in addition to it we had a, I guess you could call it cheder, or a rabbi tried to teach us a little bit of Hebrew…

PRINCE: Tried?

KOENIG: …Jewish history, and…everything was fine and we went along with it because grandpa, who lived with us, his father, seemed like the older he got, the more religious he got and insisted that certain things be done a certain way. And I guess in order to pacify grandpa, they had felt it was a good thing for me to be going to this cheder.

PRINCE: What did you call grandpa then, in Poland? What did you call your own grandpa in Poland?

KOENIG: Dziadek.

PRINCE: (PAUSE) And your grandmother was no longer living?

KOENIG: No. Grandmother died when I was, like, three years old, she died.

PRINCE: Back to the non-Jewish school, the public school. How did you – what did they do? How did you feel uncomfortable?

KOENIG: Well, first of all, and… (TAPE STOPS)

PRINCE: Did you feel the anti-Semitism from the teachers as well as from the children?

KOENIG: Basically yes.

PRINCE: Okay, so your friends were, your childhood friends that you played with were Jewish.

KOENIG: Not only, no. We had some – we had some very good friends. Dad had a few Gentile friends who I was very friendly with their children. And, a matter of fact, there was a traditional thing for us to be invited to their homes during Christmas season. It was always one evening we always looked forward to because the Christmas tree and all the celebrities that went on – celebrations, pardon me, that went on were very intriguing to us. We enjoyed it.

PRINCE: Did they have an equivalent of a Santa Claus or something?

KOENIG: Oh yes.

PRINCE: What – did it have a name?

KOENIG: Swiety Mikolaj.

PRINCE: Okay.

KOENIG: This is translated to Santa Claus.

PRINCE: Um, what kind of games did you play when you were young? You know, we play baseball, we play football…

KOENIG: No, no. We don’t play baseball in Poland –

PRINCE: I know, I know.

KOENIG: We don’t play baseball in Poland. Well, soccer was very, very popular. And…

PRINCE: Did you play soccer?

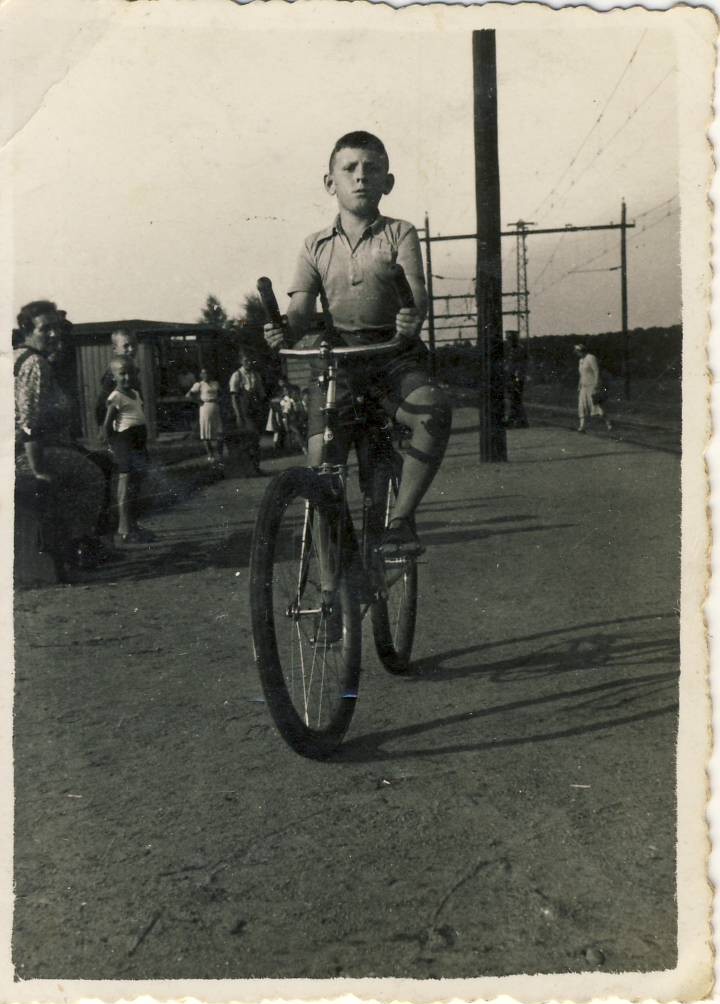

KOENIG: A little bit, not very much. At that time I was not very athletically inclined.

PRINCE: Well what – what did you do in your free time? Did you have free time?

KOENIG: Sure, we had free time. We played with the other kids, we went hiking, and, hide-and-seek. And of course, a lot of our time was spent helping around the house because even though our family was very well off, still when you compare the living standard that we enjoyed with the living standard here in the United States, things were rather primitive. I remember very distinctly when…we wanted to wash our hair which was done once a week. Friday night you took a bath and you washed your hair and it was very important that you had nice, soft water. And my job was to go to a little stream and get this nice, soft water, because the water that you got out of the faucet, if you washed your hair with that water and the regular hand soap that we had, you wouldn’t be able to comb it for two weeks. (LAUGHTER BY BOTH) So we had to get the soft water from the creek. (OVERTALK) It was nice, yeah. The other thing was, I helped my mom a lot with cooking and with cleaning the house. It was a large apartment in this apartment house that they had owned, and it had quite a few rooms and beautiful wooden floors, hardwood floors, which had to be waxed, which had to be buffed. And it was my job. And I remember we had a great big cast-iron buffer, the heavier the better. In fact mom used to put my brother on top of it to make it a little heavier.

PRINCE: Oh. (LAUGHTER)

KOENIG: So we buffed the floors with it. So anyway, a lot of our time was spent simply –

PRINCE: Spent at home.

KOENIG: Right. And things that people don’t do here, was, for example, in fall we got some cabbage and we made sauerkraut, and uh, pickles, we made sour pickles. We got cucumbers and mom had a wonderful recipe for making sour pickles. Anyway, those were the things that you ate through the winter. We had to obtain a supply of potatoes, and coal to keep the place warm. So really, even as a youngster, we really didn’t have that much free time. Plus the fact that the schools were quite strict and there was a lot of homework to be done. So between the homework and between the chores that had to be done, there really wasn’t that much free time.

PRINCE: So your existence was well-taken up with being a part – more a part of what was going on and helping out.

KOENIG: Very much so.

PRINCE: Umhmm. Okay, did your parents…when the weekend would come, or when they would enjoy their friends, did they have people over, do you remember? Did they go out? Did you – did someone stay with you or did you go with them? How was that handled, as a social…

KOENIG: Well, mom had a girl that stayed at our house that was helping her with the daily chores, you know, call her a maid, or whatever.

PRINCE: Did she live there?

KOENIG: She lived with us, right, right. So there was no problem when mom and dad wanted to go away. We liked her very much and she treated us very nicely and we enjoyed being with her. We could get away with a lot more than when mom was around, so we enjoyed it. And we were so very close to Warsaw that mom and dad frequently made trips to Warsaw. And really, in Pruszkow there was not much opportunity for going out in the evening and for entertainment. And I really think that if they wanted, let’s say go to theatre, anything other than a movie, then they had to go to Warsaw.

PRINCE: Would you classify, if we can use that word, yourself as a Conservative, Orthodox, Reformed…

KOENIG: Myself? Reformed.

PRINCE: Then.

KOENIG: Reformed.

PRINCE: Then also.

KOENIG: Right, which really, the word Reform –

PRINCE: You were assimilated.

KOENIG: – really, no, no, we were not assimilated, no. There was no –

PRINCE: No assimilation.

KOENIG: No assimilation, on our part at least. There were Jews that did assimilate, that did…change their religion, became Catholic. That was not too uncommon.

PRINCE: I meant assimilate as far as not a conversion, but just to…not be an observant Jew.

KOENIG: Okay, uh (PAUSE) the force behind our observance was grandpa –

PRINCE: …was grandpa.

KOENIG: – who lived with us, okay, so we really couldn’t get away with too much. We did keep a kosher house because of him. It wasn’t because mom or dad really wanted a kosher house. We – grandpa went religiously to synagogue. It was my job to carry his little tallis for him so whenever he went to the synagogue I went with him.

PRINCE: Is that because…

KOENIG: That was very common. It was one of the traditions that the youngsters carried grandpa’s tallis when he went to synagogue.

PRINCE: Okay, thank you.

KOENIG: They didn’t really have to stay there with him, but it was just – that was the thing to do, to have your grandson go with you to the synagogue. He goes Friday night and then Saturday morning.

PRINCE: So you observed Shabbat.

KOENIG: Uh, grandpa did. In other words, he didn’t really force me to go with him to the synagogue. But there were – there were times when I – I wasn’t a complete stranger there…

PRINCE: But I mean, did your family observe?

KOENIG: I really don’t recall. Well (OVERTALK) I’d have to say that occasionally dad would go with grandpa to the synagogue, but not very often.

PRINCE: But was Saturday a day of…

KOENIG: A day of rest? Yes.

PRINCE: Where nobody rode in a car or whatever…

KOENIG: That is right.

PRINCE: So you did observe…

KOENIG: You didn’t buy anything and you didn’t carry any money and you didn’t write, and you were on Saturday and this – it was just absolutely necessary.

PRINCE: So living that way you would still call yourself Reformed, in those days.

KOENIG: In those days, yes. In other words, if you asked my grandpa what he felt about my dad, or my mom, or about me or my brother, we were goy.

PRINCE: Even… (LAUGHTER BY BOTH) (OVERTALK)

KOENIG: …no doubt about it. Okay, so, eating what I, covering on your head, and eating things that, he knew that outside the house we were eating things that were not kosher…and so…he wasn’t happy about it, but we compromised.

PRINCE: Where did he think you went when you used to go celebrate your friend’s Christmas? (LAUGHTER)

KOENIG: That’s right, so, uh…

PRINCE: Did he know?

KOENIG: Oh sure.

PRINCE: He had a… (LAUGHTER)

KOENIG: But, well, he was – like I said before, as he was getting older, he, and especially when he retired from the business and turned it over to dad, he just – what else was left for him? So he would spend more time at the synagogue, he would spend more time debating religious subjects with his friends, paid much closer attention as to how my mom was running the household, it was kosher and all…

PRINCE: He had to have some stature.

KOENIG: Sure.

PRINCE: Before we move on, are there things that, in jogging your memory, that you’d like to talk about?

KOENIG: (LONG PAUSE) Well, about the only thing I can say is that really, my memories of my childhood, and pre-war years, are good. It was a good life. And even though it was quite different than kids my age would be experiencing here in the United States, and now that you look back on it and we say, “Well, you had it rough, and things weren’t as easy as they are here.” Of course the United States went through a depression too and not everybody had it very easy here either. But in general I would have to say that the nine years between my birth and 1939 were very good years.

PRINCE: Well, we are not, what’s important, is that we are right now back in those days and projecting ourselves back there as best we can in trying to recreate what that was. Nothing can quite compare with what goes on today –

KOENIG: No, that’s true.

PRINCE: – in an American home…What was your first memory?

KOENIG: (LONG PAUSE) Hmm, well there are things that I remember very vividly. I remember – I remember our apartment, I remember some of the furniture, I remember the arrangement. One of the things that sticks in my mind is the fact that you couldn’t get from one room to another room without walking through all the other rooms. In other words, if you wanted to get from the kitchen to the bedroom, you walked through all the other rooms. There was no such thing as a hallway where the rooms were on each side of the hallway. And the rooms were very large with very high ceilings. Each room had its own, I guess you would call it a furnace, white tile and you probably know that winters in Poland were very severe, and we slept under the – help me out. What are those…

PRINCE: Downs, comforters, quilts…

KOENIG: Comforters, quilts, great big ones.

PRINCE: Was there a name for them?

KOENIG: Pierzyna, the Polish name was koldra actually. (PAUSE) And it sure was nice if somebody got up earlier and made a fire in one of these big furnaces to keep the room warmed up.

PRINCE: Ummhmm.

KOENIG: And there was no such thing as storm windows. We had some glass windows. And starting somewhere around October or November, there was frost on them all the way through April or May.

PRINCE: How did you make the fire, wood?

KOENIG: It was started with wood and coal.

PRINCE: And who was that somebody?

KOENIG: Well, it all depended. Most of the time it was the maid who would get up earlier and start the fire.

PRINCE: Did you share a room with your brother?

KOENIG: (PAUSE) You know, that’s something I can’t remember. That is something that’s completely wiped out of my memory. I really can’t remember.

PRINCE: In other words it could be so good or so bad… (LAUGHTER)

KOENIG: I can remember parents’ bedroom. Oh no, it wasn’t bad at all. It wasn’t bad at all. It was – okay. There was one, I remember my brother’s bed, and it was in parents’ bedroom, and I know that I never wanted to sleep with him because being three years younger and he would have accidents and wet his bed and he was – he was pretty sloppy in general and all…

PRINCE: (LAUGHTER)

KOENIG: Mom said I never wanted to have much to do with him because he would mess his pants, and they always reminded me that, “You were clean, and Michael was always dirty.” (LAUGHTER) But, so I never wanted to sleep with him, but his bed was there, and I can’t remember where I slept.

PRINCE: Okay, let’s do move on to the fact that you remember that people were talking about, this is 1939 now, and they were talking about something happening, I suppose, getting ready. In other words, you remember conversations. Was it a dinner –

KOENIG: Yes, yes, dinnertime, and, there was an awful lot of talk about the possibility of war. People were making preparations by digging ditches and pasting up the windows, and an awful lot of talk about the possibility of gas warfare, about masks, and we expected – the threats were being made by Germany at that time. The pretext was the Danzig corridor that they wanted, and supposedly Poland was not willing to provide it for them. And also, prior to September of 1939, we had a little experience with some German Jews who were expelled from Germany, I think in 1938, just about a year before the war broke out. Germany simply planted them on the border.

PRINCE: Zbaszyn.

KOENIG: …said, “We don’t want you in our country,” and Poland wasn’t too willing to let them in either, and eventually they did

PRINCE: It was Zbaszyn, or I can’t pronounce it, but that’s where it was. It starts with a “z.”

KOENIG: Uh, I’m not following. What was it?

PRINCE: It was the name of a town.

KOENIG: (PAUSE) Oh, where they were – sat on the border.

PRINCE: Umhmm.

KOENIG: Yeah, I can’t remember that either. I think you’re right. I think you’re right, but I can’t remember that…Of course there were many of them. I don’t know if they were all in one town, or several border towns, but, anyway, yeah, a few families, German Jews, ended up in our small town of Pruszkow and, as a matter of fact, I became very friendly with one of them…