PRINCE: My name is “Sister” Prince and I am interviewing Mendel Rosenberg for the Oral History Project of the St. Louis Center for Holocaust Studies. Today is June 11, 1985. Mendel before, the first thing I would like to ask you is when were you born?

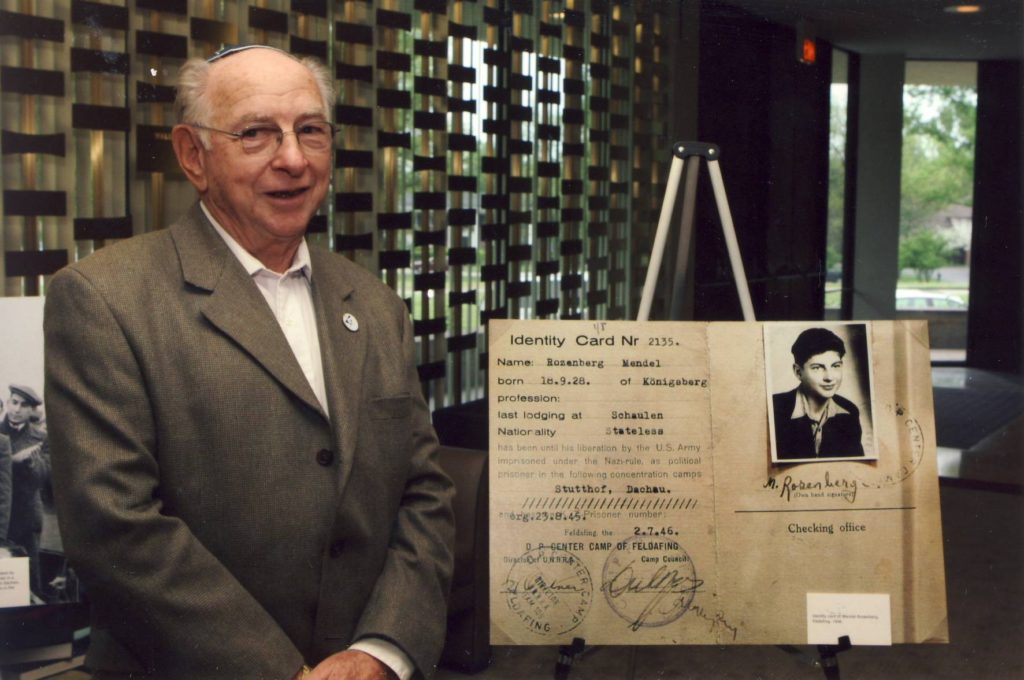

ROSENBERG: I was born on September 18, 1928.

PRINCE: And where?

ROSENBERG: I was born in Germany.

PRINCE: All right, and where in Germany?

ROSENBERG: Koenigsburg.

PRINCE: Okay, and can you continue on and tell me what…I believe you moved.

ROSENBERG: Yes, we moved out of Germany. I don’t remember exactly the year when. We moved to Lithuania to Shailiai. And I grew up in Shailiai, Lithuania which is the second largest city in Lithuania. We lived a rather comfortable life in a very Jewish, uh, how shall I say, environment. Mostly in Lithuania, we had a very liberal, in other words, the Jews lived a very nice life where we were not persecuted because we were Jews. On Saturdays and holidays, most of all the Jewish businesses were closed. As a matter of fact there used to be a market day and when it fell on Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur, uh, the markets were closed because there was no use coming in because all the Jewish businesses which were mostly in Shailiai were all closed. I remember mostly going back to about 1937, because that sticks in my mind, because we used to go every year to summer vacation to the seashore. That particular year we went to Latvia to the seashore and which is the neighboring country of Lithuania and that’s why this year sticks so vividly in my mind. We lived a rather comfortable life. My father was in the clothing business. We were manufacturing and selling in a store, a retail clothing, and…

PRINCE: Did you have brothers and sisters?

ROSENBERG: I had one brother, an older brother, a year and a half older, was killed in the concentration camp in Dachau in 1945, as a matter of fact, in January of 1945 and we were liberated in May in 1945.

PRINCE: What was his name?

ROSENBERG: His name was Samuel.

PRINCE: What was your father’s name?

ROSENBERG: Simon…Shimon. Needless to say that we were not called by American names. We were called all by Jewish names.

PRINCE: What was your Jewish name?

ROSENBERG: Mendel…Menachin, Mendel.

PRINCE: What was your mother’s name?

ROSENBERG: Recha.

PRINCE: Recha.

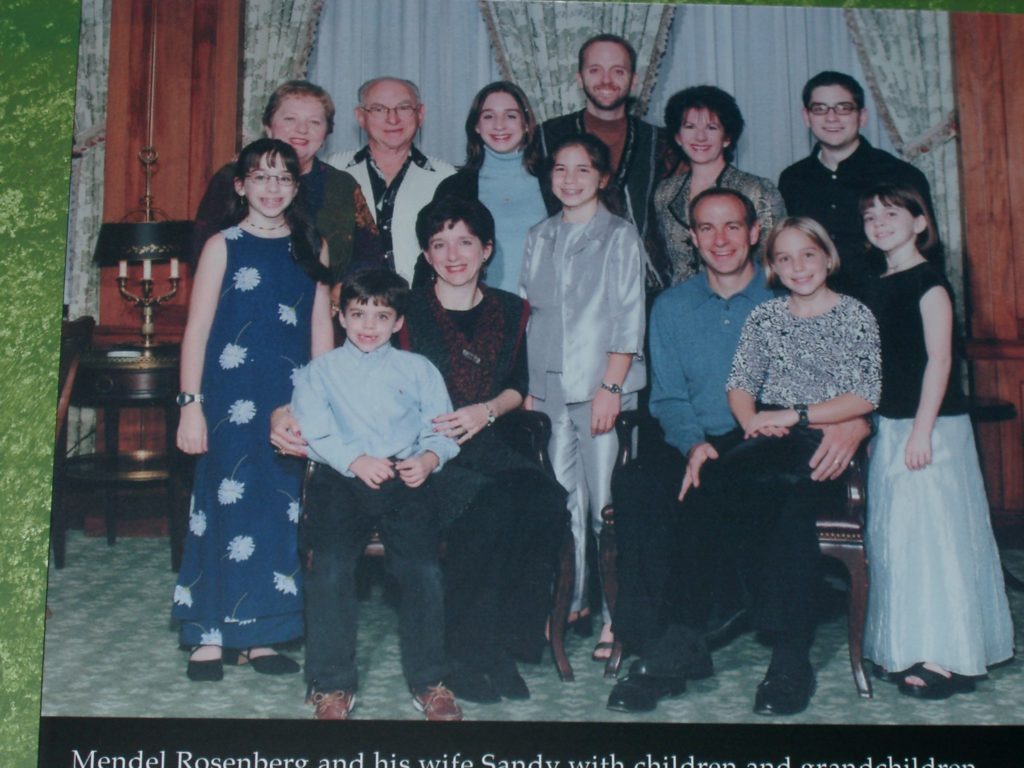

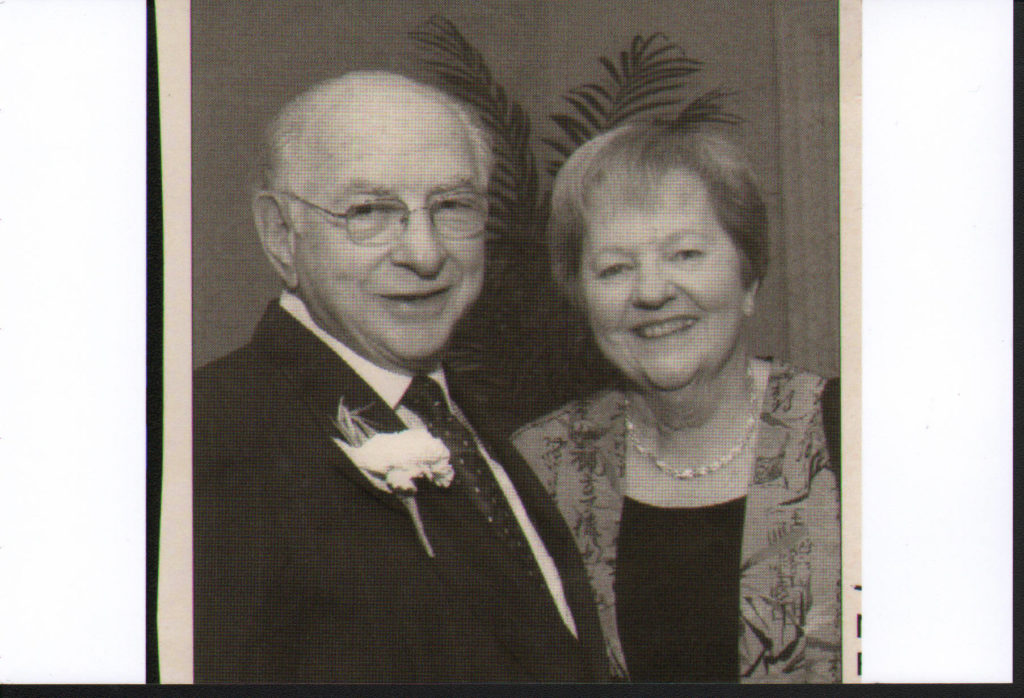

ROSENBERG: Recha. She also survived the concentration camp. She was in Stutthof and she survived. She was liberated by the Russians in 1945. She stayed on there until she found out that I was alive and I was in Munich and she told some messengers and she told me to stay in Munich that she’s coming back, to Munich.

PRINCE: And did she?

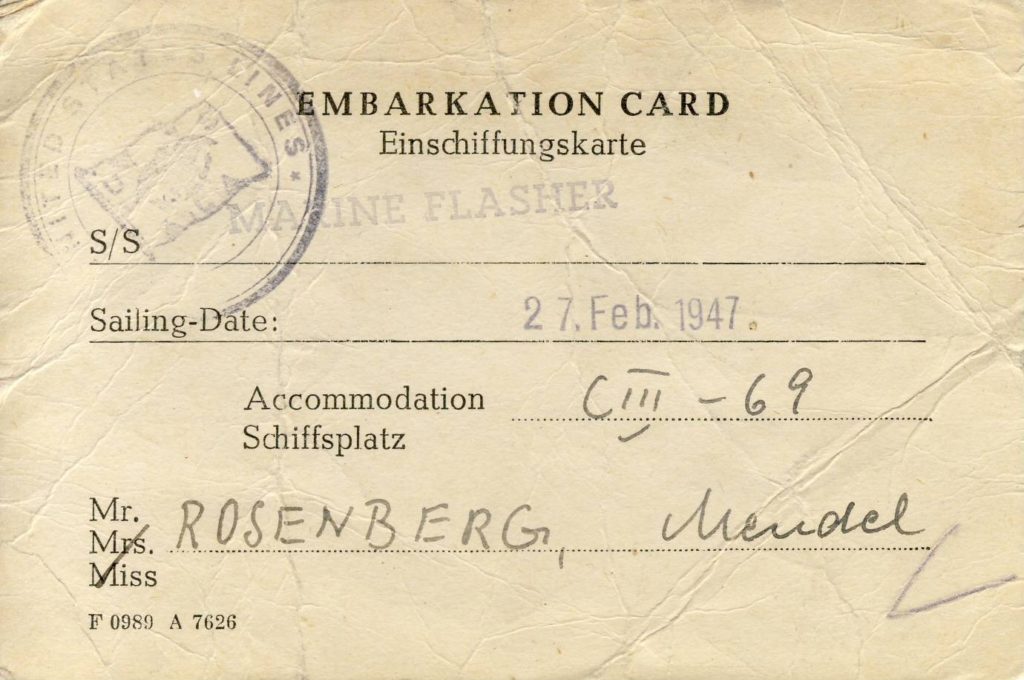

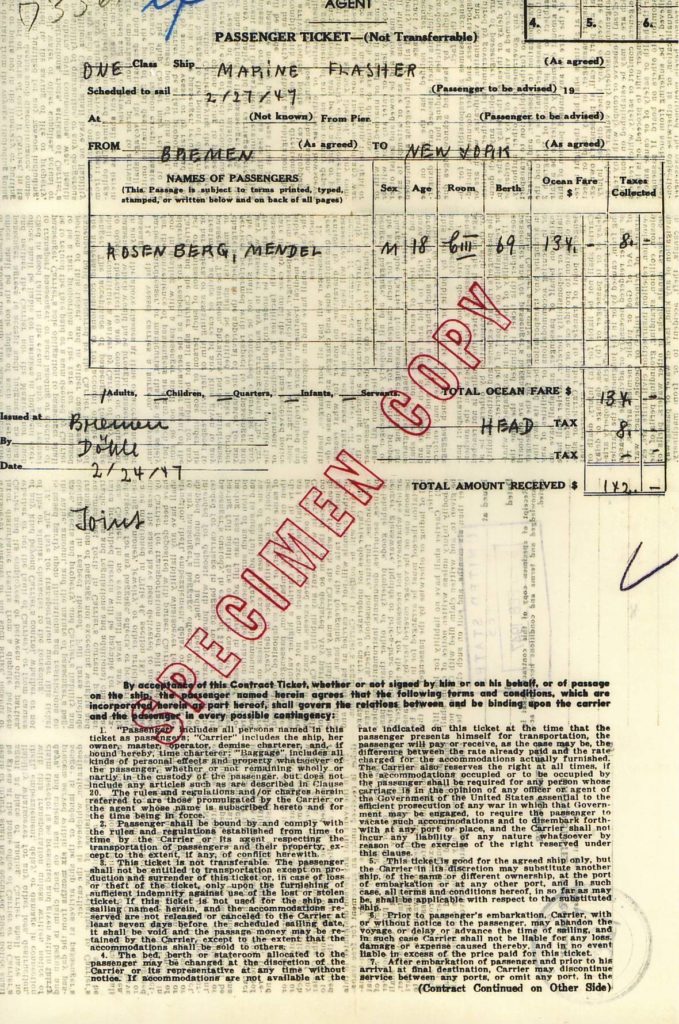

ROSENBERG: She finally came to Munich in 1946. And in 1947 we finally immigrated to the United States.

PRINCE: Now we have to go way back and start…

ROSENBERG: Now we go back…

PRINCE: We go back to when you were nine and you went to Latvia…

ROSENBERG: And we went to Latvia, that’s why it sticks out in my mind so much.

PRINCE: Was it happy?

ROSENBERG: It was very good. We had a very good childhood, my brother and I. And like I said, my father had a business and every year as soon as school was out in June, we used to go to the seashore, they called it a dacha and we used to go to Palangen most of the time and we used to stay there all during the summertime and then September used to come again and we used to go back to school.

PRINCE: What kind of school?

ROSENBERG: We went to a private, Hebrew high school. That’s where I learned most of my Hebrew because all the subjects were all taught in Hebrew. When you graduated from there, you probably could go to any state university. One of the main reasons that we went too, is number one, it was a Jewish school, everything was taught in Hebrew and number two was that my parents planned, that when we grew up then we’ll go and finish high school, then we would go to Israel and we would go to college over there.

PRINCE: Oh, they did.

ROSENBERG: So primarily that’s why we were all learning everything in Hebrew. Uh, we were in Shailiai, uh, till 1941. In 1941…in 1939 – I gotta go back – in 1939 when the war broke out with Poland, uh, Germany and Russia made an agreement where the Germans went into Poland and the Russians came into Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. When the Russians came in, they forced – we were considered bourgeois, and we were considered rich people so they confiscated the business and the house and the buildings and everything that we owned. And my father was out of a job and we were still going to school but instead of going to private school, we ended up to going in a regular school…public school.

PRINCE: And with non-Jewish children?

ROSENBERG: No, all were Jewish children, but in a public school. In other words, we had two different types of schools at that time. We had private schools where everything was taught in Hebrew. We had public schools that, well, maybe we shouldn’t be calling them public schools, we had schools where a lot of the subjects were taught in Jewish, and then we had schools that all the subjects were taught in Lithuanish. We went to a school that all the subjects were taught in Jewish.

PRINCE: The ones that were taught in Lithuanian were non-Jewish?

ROSENBERG: Non-Jewish.

PRINCE: Were they ever mixed? I mean, did ever Jewish children go to the non…

ROSENBERG: Yes, some, but very few, very few. Most all the Jewish kids went in Jewish…whether it was in Hebrew or whether it was in Jewish.

PRINCE: So Mendel, did you have any associations with non-Jewish people?

ROSENBERG: I, personally, as a kid only had the association with non-Jewish – with the neighbors, the kids that we ran around in the neighborhoods where we lived.

PRINCE: And were they friendly?

ROSENBERG: Yes, they were friendly.

PRINCE: So there was…was there any anti-Semitism…?

ROSENBERG: As a kid…

PRINCE: As a child?

ROSENBERG: …I did not feel any anti-Semitism at all in Lithuania. I understand that during the war and when the Germans came in, some Lithuanians were helping the Germans greatly. Some…some, not many, but some also helped the Jews. I know some relatives of mine where the kids were hidden with the Lithuanians all during the war. That’s what my mother told me and that after the war, the kids didn’t want to come back. The kids were raised with them on the farm and the kids stayed there and they grew up and when my mother last saw them, they were Lithuanians.

PRINCE: What’s the first memory you have?

ROSENBERG: Going back?

PRINCE: Uh mmm…

ROSENBERG: I don’t know, I couldn’t even tell you the year.

PRINCE: Well it doesn’t have to be the year, just the…

ROSENBERG: But greatly the memory I had is going back to around 1935 or 1936. I remember because as a kid, going to the store and there were some calendars and I remember looking through the calendars, that’s when I remember those years.

PRINCE: Did you go to the store for your mother?

ROSENBERG: No. We used to go in the store after school, we used to come to the store because my father and mother used to work. And both of them were in the business, yeah.

PRINCE: Did you ever help?

ROSENBERG: I was too little for that. They were very happy that we stayed out of the way, but in later years, I can remember the store very vividly… ’37, ’38.

PRINCE: Can you describe it to me?

ROSENBERG: Yeah it was about two blocks away from where we lived. It was on Vilnaus Gatve – that’s the name of the street in Lithuanish and we had two people helping my father and my mother in the store. And there was two…a lot of rolls of clothing hanging, ready made clothing and we also had, uh, cloth and what people used to come out and pick out from the cloth and we used to make them the garments for them.

PRINCE: Was it a wooden…or brick?

ROSENBERG: Brick buildings.

PRINCE: Brick building.

ROSENBERG: Mostly all the buildings were brick, mostly all the buildings where we lived were downtown. In Europe they used to be most of it where the businesses were on the ground floor and people used to live on second, third or fourth floor. The house what we owned was also businesses on the ground floor, while our store was not in our own building, uh, the businesses were on the ground floor and we lived on the second story, and we had the first, second, third and fourth story.

PRINCE: Did you, uh, attend synagogue, or…?

ROSENBERG: Oh yes. We used to attend synagogue every Saturday and every Friday night and every Saturday morning. For Passover, for instance, we used to get uniforms. We used to wear uniforms to school. As a matter of fact, I’ve got some pictures here…

PRINCE: Oh wonderful.

ROSENBERG: If you would be interested.

PRINCE: Oh of course.

ROSENBERG: I can dig out some of the pictures as little children. Number one, we had some relatives in the United States where we from Europe sent pictures to the United States. Number two is, uh, we didn’t have any kind of pictures of anything left from them so all the pictures and everything we’ve got is what I found when we came to United States of America.

PRINCE: People gave you back?

ROSENBERG: No – that my cousins, yeah, they gave us back those pictures that we had. Uh, those were the pictures when we were kids. So, for Passover we used to get new uniforms…every year.

PRINCE: What did they look like?

ROSENBERG: They were completely black pants, long pants and completely, how shall I say it more, completely black jackets with closed collars.

PRINCE: No lapel?

ROSENBERG: No lapels.

PRINCE: Like the Beatles.

ROSENBERG: No lapels, completely closed, like a narrow jacket.

PRINCE: English.

ROSENBERG: And that what we used to get normally every Passover for a new one.

PRINCE: White shirt?

ROSENBERG: White shirt, but you couldn’t see the shirts underneath.

PRINCE: Oh I see.

ROSENBERG: Uh, needless to say, that school was out for Passover, for the whole eight days. Every Jewish holiday, we used to be out of school. All the holidays was strictly observed, Passover, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and all the holidays were very strictly observed. I would say that we were grown up mostly in a very strict Orthodox sense. The only thing is that we didn’t know any different. We didn’t know, in those days in Europe, about Conservative or about Reform. Because we didn’t grow up in that kind of environment.

PRINCE: But it wasn’t Hassidic.

ROSENBERG: No, it was not Hassidic type of environment.

PRINCE: You’re very emphatic about that.

ROSENBERG: It was strictly a Jewish, Orthodox environment. We used to go and daven every Friday and Saturday morning. We used to walk to shul because everything was very close, we didn’t have to ride no place although we wouldn’t ride anything. Uh, number two, is we understood everything that we were praying because we understood fluently, as a kid, we understood fluently, Hebrew, Jewish, Lithuanish and as years went by, German and Russian. All those languages, I could speak fluently. And we grew up with all that and we went to school with all that and all those languages was physically learned in the schools. When the Russians came in, we learned Russian and German and before that we learned Hebrew, Lithuanish and at home we spoke in Jewish. All the conversation at home, among the parents and ourselves, was strictly in Jewish.

PRINCE: Jewish,…or Yiddish?

ROSENBERG: Yiddish. Yiddish and Jewish are the same.

PRINCE: Same?

ROSENBERG: Yes.

PRINCE: I want to make that…

ROSENBERG: Jewish and Yiddish was the same thing. Still, even today, to some degree, while I added a little bit of English to my vocabulary, uh, I forgot during the 40 years that I’ve left Europe, I forgot almost entirely Lithuanish…very little German and very little Russian. The languages that I still do handle very well is Yiddish or Jewish, Hebrew and English. Hebrew, I never forgot. When I go to Israel, for instance, I speak down there with them and everybody asks me, “Well when were you here and where did you live? When were you in this country?” I say, “This is my visiting, I’ve never been here,” but I can still speak it rather well.

PRINCE: Like a native.

ROSENBERG: I wouldn’t say, “native,” but I speak rather well for a foreigner of Hebrew.

PRINCE: Uh, so you were very comfortable…

ROSENBERG: Yes, very comfortable.

PRINCE: And were always (OVERTALKS)

ROSENBERG: As a matter of fact is, while the Russians came and confiscated everything, we still lived for two years, till 1941, till the Germans came in, without much of a support from any kind of income.

PRINCE: Uh, that is exceptional, that’s exceptional.

ROSENBERG: Yeah. We each very easy to look at hindsight and ask the question of my parents is why didn’t we leave Europe at a time because we could have left Europe. But it is the same thing, “hindsight” is very easy to look up today and say to myself, “Why didn’t my parents leave?” We did buy some land in Israel before the war. We did have plans to go to Israel.

PRINCE: Were you, were you Zionists, would you say, or…

ROSENBERG: Yes, we were Zionists, we can say, as kids we belonged to the Betarim . In those times, it was Jabotinsky’s group and we went to meetings and we participated. We had little uniforms and all that stuff as kids and we were planning, matter of fact, is very strongly, to go to Israel as soon as we finished high school.

PRINCE: Would, uh, right and go to college, you said that. Do you think your parents would they come there?

ROSENBERG: Sure, sure we all wanted to do that. As a matter of fact we bought some, we bought some land in Yachnam way before, 1938, I think.

PRINCE: Mendel, what were they waiting for?

ROSENBERG: What were we waiting for?

PRINCE: I mean besides the war, before the war.

ROSENBERG: I don’t know. They were waiting for us to graduate from high school I guess. And then, after we would have graduated from high school, we were planning to go to Israel, to go to college.

PRINCE: And everybody would have gone, all right…

ROSENBERG: At that time, yes.

PRINCE: Uh, what did you do for fun as a child?

ROSENBERG: As a child what we do for fun? Well, bicycle riding was very great over there. Free time, a lot of free time, we didn’t have. We used to go a lot of ice skating. I remember we could ice skate as soon as we started walking, we could ice skate. As a matter of fact is in school where we went to, one of the subjects of – how shall I say that – of…

PRINCE: Curriculum.

ROSENBERG: Curriculum. One of curriculum was ice skating. We used to go to…have classes in ice skating. As a matter of fact they used to teach us to go ice skating during the school year.

PRINCE: Was it like a gym…gym time?

ROSENBERG: Like a gym time, like a gym time, like a gym classes. Instead of playing basketball or soccer or that kind of stuff, we used to also have classes in the wintertime, ice skating, and we used to take the tennis court, we used to pour water all over the tennis court and go ice skating…

PRINCE: At the school.

ROSENBERG: At the school and we used to go ice skating. We used to all play, not me, as I was too little, but they used to play tennis there. But we used to pour water over it and we used to freeze it and we used to go ice skating.

PRINCE: So ice skating and bicycle riding and…

ROSENBERG: And skiing.

PRINCE: And skiing.

ROSENBERG: Right. As a matter of fact, is after the war, when I was in Germany I went to Garmich Partenkirchen to ski there. I’ll show you some pictures of that too.

PRINCE: (LAUGHTER) Okay, alright, well what am I not asking you about growing up that you might want to tell me?

ROSENBERG: What we use to about growing up?

PRINCE: Tell me about your mother.

ROSENBERG: My parents, I would say, were average.

PRINCE: In what way, average?

ROSENBERG: In what way? We used to have a lot of friends and we used to be called, not that I’m trying to be snobbish about it, but we used to be called the higher level, or the better class of the Jewish people in the city. In other words, we had donated a lot to the temple and we used to donate some money to the Jewish movements and we used to, uh, all those things I found out afterwards, when my mother used to get in a conversation. They were very well educated. My mother went to school in Moscow to the university and she could speak all the same languages, plus French and Latin, not speak Latin…read in Latin. And this is what I was considering a higher level because in Europe, uh, a lot of people were just living with a every day living, with a every day, uh, going on how to make a living. We were lucky that we could afford a lot of those things, a lot of the nicer things in life.

PRINCE: Mendel, where did you – until you gave which lovely…

ROSENBERG: Right.

PRINCE: …You know, that you had it and you gave it. What about your grandparents because were born in Koenigsburg.

ROSENBERG: The grandparents that I remember is my father’s parents, I only saw once in 1937. They lived in Latvia.

PRINCE: Now, who, what I’m trying to find out who’s really from where.

ROSENBERG: …My father’s parents…

PRINCE: Right, were they Latvians…and…?

ROSENBERG: No, I don’t know to tell you the truth exactly where they come, all I know that we lived in Lithuania. I didn’t even know ‘till a lot of time later that we were born in Germany. My mother traveled a lot. Her parents traveled a lot. She went to school in Russia.

PRINCE: Okay. Where were her parents born?

ROSENBERG: I don’t know where her parents were born but I know she was born in Germany also in Tilzit, Germany. But they traveled a lot and she was going to school in Moscow of all places. But then, they settled down, the parents settled down in Lithuania because the things in Germany were not very good in those days so they moved into Lithuania.

PRINCE: Into Prussia.

ROSENBERG: And my grandfather, I don’t remember well, I only remember him from pictures. He died, that’s my mother’s father. My grandmother died in the ghetto. My grandmother, my mother’s mother lived with us in the ghetto.

PRINCE: May I try and pronounce it…is it Shailiai?

ROSENBERG: Shailiai.

PRINCE: Shailiai.

ROSENBERG: Yes.

PRINCE: Shailiai.

ROSENBERG: In Jewish, it’s Shailiai. In Lithuanian it’s Siauli, but in Jewish it’s Shailiai.

PRINCE: Shailiai.

ROSENBERG: My grandmother lived till 1942 in the ghetto in Shailiai.

PRINCE: Let’s…let’s begin now…let’s begin with how things might have changed, till you were living this life that you just described to me and when did you, as a child, not…when did something big happen. But when did you, as a child, sense that there was something different about your life and it was changing?

ROSENBERG: That was in 1940, late 1939 until ’40 when the Russians came in.

PRINCE: Did you hear any conversation at home between your parents, around the dinner table at any time that things…

ROSENBERG: Yeah, we knew at that time, that they confiscated everything that we owned…

PRINCE: So it was just one, two, three, they came in and…

ROSENBERG: One, two, three when they came in…

PRINCE: …That was it.

ROSENBERG: It didn’t take very long, no. As soon as they came in…one, two, three, they start confiscating everything.

PRINCE: Did you know they were coming, or did they just…?

ROSENBERG: No, we did not know in advance that they were coming. They just came in and that was it. Probably if we would have known, maybe my father knew but I didn’t know about it…Maybe we should have left at that time. That was the best time to get out, was in 1938…the beginning of 1939 but we didn’t do it. Some people went out as late as 1940 and they left the country. The Russians didn’t let them get out so easily because they took everything away.

PRINCE: So you were…the Russians came…in 1940 you were 12.

ROSENBERG: 1939, they came in late 1939…early 1940.

PRINCE: Okay, so you were 12.

ROSENBERG: At that time, right.

PRINCE: How did your life change?

ROSENBERG: The life didn’t change as for me personally except that we went to a different school and everything was taught at that time in Jewish. Aside of that, much didn’t change.

PRINCE: And your father…had…okay…

ROSENBERG: Father didn’t have any work. Finally he got some work on a construction job but that was about all the change. And my mother didn’t have to go to work anymore. The only thing that changed is the Russians put in soldiers in our home. They took away two of our rooms and they put in Russian families with us. And the biggest fight in those days was the kosher kitchen that we had and the Russians were coming in and they were trying to cook something in our kitchen.

PRINCE: How did that get resolved?

ROSENBERG: How did it get resolved? Uh, we got some electric plates, electric heating plates and we gave it to the Russians. We asked them to cook their meals in their own rooms.

PRINCE: And did they?

ROSENBERG: They did because they were in military personnel and in most of the cases, they tried to get along with the civilian personnel.

PRINCE: Did they differentiate between the Jewish and the non-Jewish population?

ROSENBERG: No, no, not the Russians at that time and not to any degree that I could tell as a child. The only encounter that I ever had with the Russians, as a child, was that we were in a park, as kids running around and I had a camera, a box camera and I was taking pictures and we were running around and all of a sudden the Russians came over and opened up the camera and took the film out because they said that we should not take any pictures of the Russians.

PRINCE: My goodness, already…

ROSENBERG: And not remember the time whether they were…I was taking pictures of Russian soldiers or wasn’t, but as a kid, we didn’t even pay much attention to those things. But I remember that incident happened.

PRINCE: So the Russians are there and then what?

ROSENBERG: And then the Russians, then all of a sudden we find out that the Germans invaded the Russians. That was in 1941 and then the way we found out was strictly that the airplanes of the Germans came in and started bombing. And we spent over a week…

PRINCE: Bombing your city?

ROSENBERG: Bombing our city and over a week, we spent primarily in the basement of the buildings, in the basement of our house. In a week, I think the whole incident was over and the Germans were in.

PRINCE: And the Russians were out.

ROSENBERG: And the Russians were out. Some of the people run with the Russians. I have some personal friends, kids my age, a little older that retreated when the Russians came in. We, as a family, we all stayed together. At that time was my father, my mother, my grandmother, my brother and myself. I had an uncle and an aunt that lived in the same town and two girls; the four of them were evacuated by the Russians right before it started with the Germans. That was in 19…early 1941 and they took them all and shipped them to Siberia. My two cousins presently live in…all the way in Siberia, in Altaiski which is all the way in Siberia – south Siberia.

PRINCE: You know that?

ROSENBERG: Oh sure, they were here for a visit…

PRINCE: Oh my…

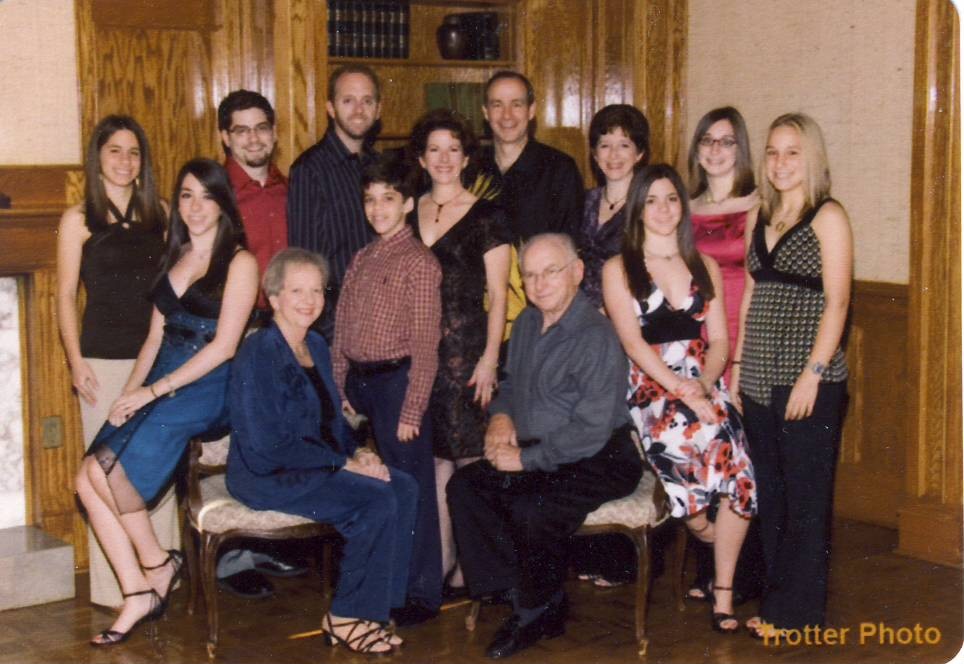

ROSENBERG: Four years ago, they were here for a visit.

PRINCE: And they went back?

ROSENBERG: They went back because they have husbands and children there.

PRINCE: I’m amazed they…

ROSENBERG: The Russians let them out. It was four and a half years ago when there was a little détente, and in those days they let a lot of Jews out of Russia and they were much more liberal in those days. So they let them out and they came here for a visit and they stayed here for a month and then they went back to Russia. Now I’m trying to get their daughters to come here for a visit, wouldn’t let them out. Now we’ve got to wait until a little politics warm up a little bit, and the chill thaws out and we hope we’ll be able to bring the children down here for a visit from Russia.

PRINCE: All right. (SIGHS)

ROSENBERG: So in 1941 right when the Germans came into Lithuania, the first thing they did is they gathered up a lot of male, Jewish people which at that time included my father and my brother. I was too little at that time. The Lithuanians…

PRINCE: Your brother was how old?

ROSENBERG: About a year and a half older than I was.

PRINCE: Yeah, right, but that made him…

ROSENBERG: That made him at the time about 15 years old.

PRINCE: Okay.

ROSENBERG: And at that time is when we felt that some of the Lithuanians – see without the Lithuanians the Germans didn’t know who was Jewish and who wasn’t Jewish. The Lithuanians helped them considerable pinpoint all the Jewish families because they knew who was Jewish and who wasn’t. They pinpointed all the Jewish families to them and they helped them gather up all the Jews and they took a lot of them into the jail, of the city jail. They left me alone, they left my mother and my grandmother alone. Needless to say, that when that happened, we knew some, a lot of non-Jewish people in the city which we tried to get help us get my father and my brother out of jail. As it happened, we managed to get my brother out but was too late for my father. My father was shot in July of 1941. The Russians came in…the Germans, I think, came in, in June of ’41. My father was shot around the fourth of July of 1941. One of the main reasons we know that date is because we were able to get my brother out on a Sunday and we know my father was shot on a Saturday morning because he was dead already when we got my brother out on a Sunday morning.

PRINCE: Your brother knew about this?

ROSENBERG: Yes.

PRINCE: How did you get your brother out?

ROSENBERG: Uh, we bribed some people and we brought him out of the…It was too late, my father was dead already.

PRINCE: Do you think that you could have…?

ROSENBERG: Yes, yes, had they not shot him that Saturday morning, we could have gotten out. See Friday night, they separated them. They separated Friday night my brother from my father.

PRINCE: The circumstances of their taking your father and your brother just because?

ROSENBERG: They just knocked on the door and they came in with their rifles and the Germans and they just took them. It was as simple as that.

PRINCE: Do you have the circumstances of why they killed him?

ROSENBERG: It was no reason, only because he was a Jew. That’s what the circumstances and why they killed him.

PRINCE: Selection process.

ROSENBERG: Selection process. I got a picture that was taken when he was separated. A friend of mine that ran away, that I told you earlier, ran away with the Russians, back to Russia, he happened, during the war, to serve in the Russian army. He came back after the war and went through the files in Lithuania. The Germans had a good knack of taking pictures of everything that went on and kept very meticulous records of everything that happened. He found a picture over there and he send me that picture of that Friday when they separated my father and the rabbi and a group of other people…separated them and shot them Saturday morning and he sent me a picture from when he was in Lithuania, he sent me a picture from there…my friend. That’s how we know when it happened with my father.

PRINCE: The picture was of…

ROSENBERG: The picture was of my father and a group of other, including the rabbis of the city of Shailiai.

PRINCE: That was quite something for you to handle.

ROSENBERG: Yes, that was after, that was, needless to say, that it was some years after the war, yes.

PRINCE: No, but I mean, when that happened. That was…

ROSENBERG: Well, we didn’t know at the time what was happening. See my father was in the jail at the time and we didn’t know what was going on behind over there.

PRINCE: How long was he in jail?

ROSENBERG: I would say a month.