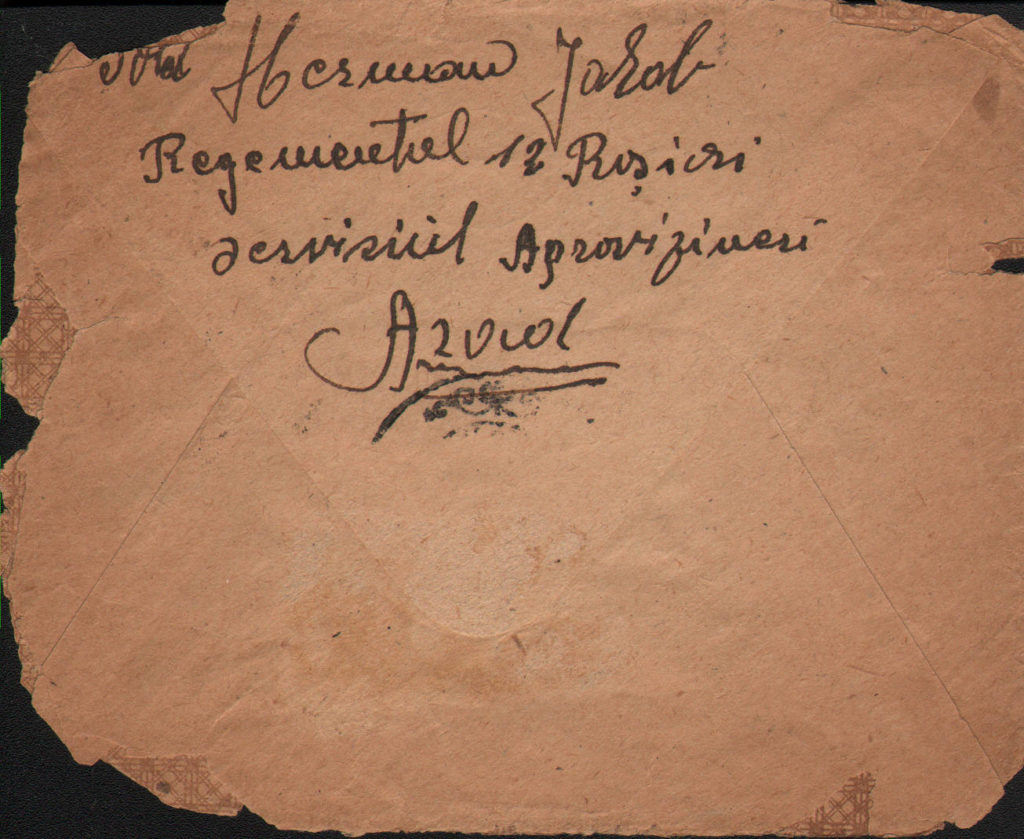

Jakob: I wanted to go back to Romania for one reason, and the main reason, I wanted to see with my own eyes if anybody from my family is still alive. My father was pleading with me…not to go back…because he was afraid…and I was ready to go back because my cousin Irving (Erwin?), he decided he was going to go back. I just could not believe that my mother, and my brother, and my sister was dead. I just…I just…I said, “If I see with my own eyes that they’re no longer there, maybe I’d believe it.” So—and also my grandparents. So, I agreed that I’m not going to go back, my father pleaded with me not to go, but my cousin, he decided he’s going to go on his own, which was very difficult for us because we’re always together. And he…he didn’t want to go without me, and I didn’t want to stay without him. So…but anyway, we agreed that he’s going to go back and see what’s going on there, and then come back to the Germany.

Prince: That was a big risk for the both of you.

Jakob: It was a big risk. And like I said, the only way he could go was hitchhike, and he had to go through Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and then into Romania.

Prince: And when you say hitchhike, do you mean jump on the train?

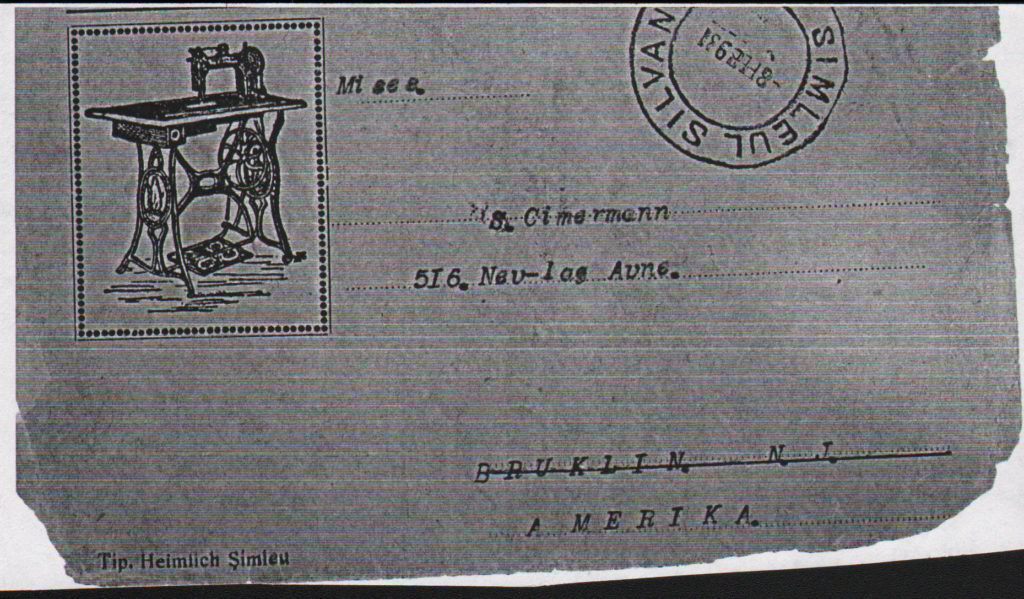

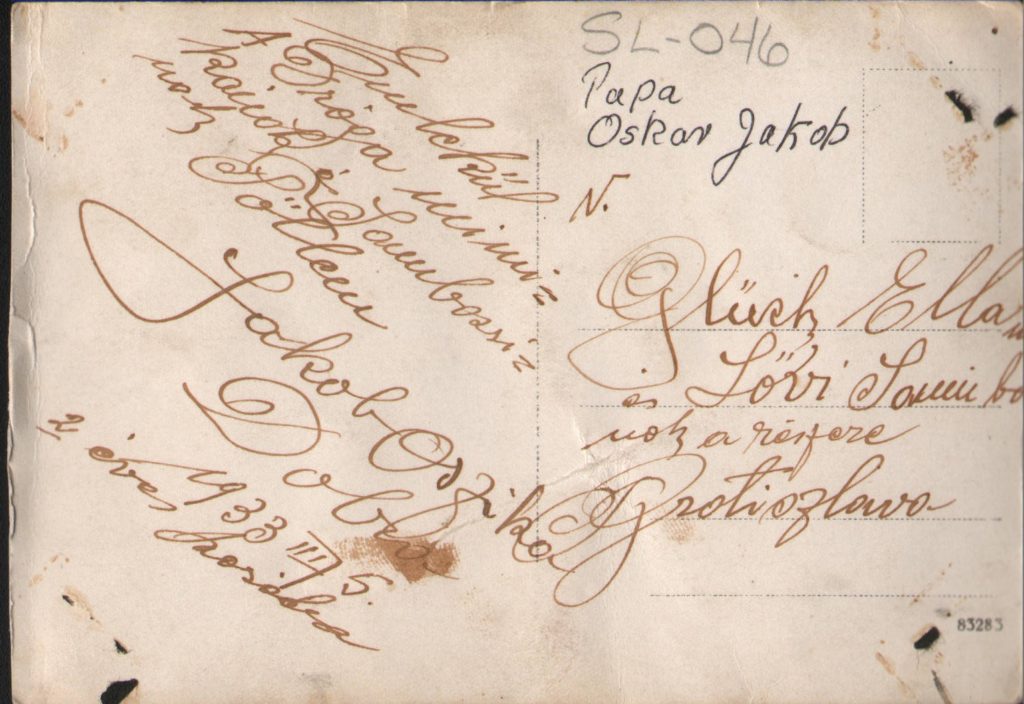

Jakob: Jump on the train, and sometimes horse and buggy. And sometimes, oxen and wagon…with trucks, with any way that you could go to certain direction. And he was gone for about four month. And he did manage to get back to Romania. Its’ funny, that when I was in New York just last week, we talked about this…we just talked about this. And he…but before he left from Germany, I told him, I said, “Look, there is a box there I want you to bring back from Romania.” And this box was when the Hungarian Nazis came and gave us two hours to pack to leave, my father gave me this little sewing box—it was Singer sewing machine box, a metal box—and he said to me, see if you can hide it somewhere, right under the nose of the Nazis. And, you know, at that time, I was a year younger, I was only thirteen years old, so…I put it in a bucket, and I was telling the Nazis, “Is it ok if I go and feed the horses and the cows one more time?” They said, “Ok, go ahead.” And it was pitch dark, you know we had no electricity, so…but I knew my way around because I’d been there everyday. So, I took a shovel in the barn, and I knew that I had to do this quick, and I didn’t feed the animals, but I made a hole, maybe I was able to dig down about eight inches, maybe ten inches deep where one of the horses were standing. And one-two-three—I took this box and I buried it in there. And nobody knew where this box was. If God forbid something should have happened to me, that box would still be there…because nobody knew about it. So, but I explained it to my cousin Irving (Erwin?), when he goes there, where this box is…and described him exactly so we…when he went back, he talked to the guy who was living in our house, you know, lived there for free…he said, “Why don’t you give me a shovel, I’m looking for something.” So, he didn’t say anything because he was afraid…I mean, after all this was after the war and he had to agree to it. But he went with him, and he watched him how he was digging this box out, and immediately he found it, he didn’t have to look too far because I told him exactly where it was…it wasn’t a big stable. So he was able to find it. He dug that, and he took it out there, and this guy was polite in his faith that he had been living in our house, using our stable and our animals and everything, and he didn’t know about this. So, he took it out and he brought it back to Germany. So, what was in the box? The box was my grandfather from my mother’s side, he was a well-to-do guy, he always did well, and he was a very capable person, and he brought all his three son-in-laws when they got married, he bought a pocket watch with a gold chain on it. And my mother had some diamond earrings, and a diamond ring, and some wedding bands, and she had a little gold watch, and there may have been something else in there, I don’t remember exactly. But this, what I just said, it was in there.

Prince: It was still there.

Jakob: Yes. So, he brought it back, and he gave it to my father. And my father was…he couldn’t believe himself that this made it after all this because all these months and weeks we were always hounded by the Germans, by the Hungarians to give up the gold and the money, and they would just not leave, on a daily basis. You know, they would tell you, “Where is your money? Where did you hide this? Where is your gold?” And here it is, they didn’t get it.

Prince: Do you still have it?

Jakob: The watch, my father when he passed away—should he rest in peace—he gave it to my sister’s husband in New York, and he’s still got it.

Prince: He gave it to who?

Jakob: I have a half-sister…

Prince: Oh ok.

Jakob: …who after my father got married, and her husband who is a rabbi, he’s got it. So it doesn’t matter, as long as it came back. I would have liked to have had it because it was for me…it was a sentimental because it came from my grandfather, and I thought it would have been more proper if I would have had it, but that’s ok, let them have it, it’s fine as long as the Germans didn’t get it, the Hungarians didn’t get it.

Prince: Right. So, Irving (Erwin?) came back…

Jakob: Irving (Erwin?) came back, and I’ll tell you it was a happy reunion. I was so worried about him that something was going to happen, but while he was there he found…let’s see…four cousins in Romania that they also went back from the camps.

Prince: In that town?

Jakob: Not in that town, but they lived in other towns, two of them lived in ____?____, two of them lived in…

Prince: How did they find each other?

Jakob: He went, he went to each of those places.

Prince: Oh, he went from town to town. Oh my goodness.

Jakob: And he found them, so…then he asked them, “Let’s go back to Germany, maybe we’ll go to other places.” Because none of us wanted to live in these places anymore, in Romania, even though there was Jews who had no place to go, at that time there was no D.P. ____?_____ from the United States that we could get to the United States. The word “Israel” was not mentioned yet, there was a Palestine, and this is where the recruitment came in from the Haganah—they were looking for young Jewish guys to come to Palestine and help create a Jewish home there. And this went…they went to all these camps and tried to find people who were interested in going to Palestine.

Prince: Weren’t most people interested in going to Palestine?

Jakob: There was quite a few interested, including me.

Prince: And more than America?

Jakob: Yes. I had more of a desire to go there than to come to the United States. I had no idea what the United States was all about—absolutely none. So, I…when they mentioned, you know, that Palestine, and they were talking about a Jewish homeland, I said, “It sounds very wonderful, you know, to be a place where they don’t hate us.”

Prince: And people want you.

Jakob: Yes. So, I really wanted to go. And again, [LAUGHS] my father put the brakes on, and I was young enough that he was able to persuade me that I shouldn’t go.

Prince: Well the fact that he had that connection to America.

Jakob: Exactly.

Prince: But, you know, you’d have been a wonder in Palestine.

Jakob: I would have lost it because my heart and soul—even though I live in this country, I have my family here, and I love the United States, don’t misunderstand me, I think this is the most wonderful country on the face of the earth. And in this country the Gentile people are completely different people than Gentile people in other countries, they just don’t have the hatred in their hearts against us. Because you can go to Poland, or Romania, or Hungary today, they still hate Jews; there’s barely any Jews left there, but they still hate you. But in this country, you’re not afraid to say that you’re a Jew. I’m not afraid to—when somebody asked me, I’m not afraid to say, I’m not ashamed to say it—there we were always hiding it. So, but even that…uh, I wanted to go to Palestine.

Prince: And they were very persuasive, weren’t they? Wasn’t the…the Brigade would come in…talk to me about that.

Jakob: They would come in, and they were…actually recruiting people not only just to go, but even how to defend yourself, they already started there, because to go to Palestine it was not an easy thing because the British didn’t want to let us in. So, it was a constant battle. Many times they loaded a ship full of immigrants, the Haganah did, and they were finding out they were heading towards Palestine, and the British stopped them, and they shipped them back to Cyprus. So…we were worried that that’s going to happen to us too. But still in all, I really really wanted to go to Palestine.

Prince: Yes, I can understand that. And how about Irving (Erwin?)?

Jakob: Irving (Erwin?) too. And until today we are strong, strong Zionists—for us, Israel is very, very important. Living as a Jew in a place where nobody wants you, and knowing that any Jew, anywhere on the face of the earth have a place now to go. And I’m certain to say, there are a lot of American Jews who were born and raised in this country do not have the same feeling, and it hurts. But, uh, listen, one thing you cannot change is a person’s feelings. I guess you have to go through the horror what we went through to have the feeling that we have for a Jewish homeland.

Prince: I’m listening to you, we’re sitting in this very pleasant room, carpet on the floor, soft lights, and…talking about Irving (Erwin?) going back, your stress level of everything that you’ve been through, plus maybe losing him, plus trying to go somewhere that you wanted to go, um your father…I mean, the food, the clothes, the health, the…was anybody around in those camps? Did anybody reach out to talk to you about your mental feelings? And did anybody…or did they have anything set up to examine you physically?

Jakob: No…we had nobody talking to us about anything. We were never examined up until…I believe it was 1948…when we registered to come to the United States. Only then we had a physical examination because if you was not physically fit, you could not come into this country. But up until then, nobody talked to us about anything, and we had no physical…checkups or anything. And I did develop a hernia in the camps, and when I did register, after the first check-up they said that I will not be able to go to the United States unless I have surgery…in Germany. So, I went into the hospital as soon as I was able to, and I had surgery in Frankfurt to repair the hernia. And, that’s the only…

Prince: And you were ok?

Jakob: Well…they butchered me up…let’s put it that way. [LAUGHS].

Prince: Did they?

Jakob: Yeah, I think this guy who did it was, I don’t know if he was even a registered doctor or what he was because I had problems all the way…it reoccurred, and I had my second surgery here in St. Louis by Dr. ____?_____, God bless him. He…I told him my problems, and he said, “I can’t promise you anything, but I’ll do my best.” And since then, thank God, I’m ok.

Prince: Alright…from what I…ok, from 1946, are we up to that point? Is there anything else about the camps? I mean, when did they begin to be, what I say organized more—there were schools, and you know, were there that kind of thing? Where did you find something, anything like that anyplace that you were that…were they just places…the places you were in, were they just places where there were lists on the wall, you had food, you could sleep, there was some Jewish life there—you said there was a synagogue—

Jakob: Yes.

Prince: But did it expand at all at the time that you were in any of the places like that?

Jakob: It expanded almost all places. Jewish learning and teaching started to flourish. And I can speak mostly in Frankfurt where we moved from Bergen-Belsen. And we lived by the way in Asheweig (?), and also was a camp, we lived there for a short period of time.

Prince: Did it have a name?

Jakob: Asheweig (?).

Prince: Oh, Asheweig, I didn’t know if that was a city or…

Jakob: But we didn’t live there too long, but we moved back to Frankfurt. And in Frankfurt, my father became active…very active…in organizing a Jewish community. And…because Frankfurt had a huge Jewish population before the war, and Zeilitzheim was not that far from Frankfurt, all you have to do was jump on the street car and you could be anywhere in Frankfurt that you wanted to be. And things were already getting better in Frankfurt, the communication was getting better, we were able to go from one place to another without much problems. So, we decided…no, I’m sorry, I should say this—we moved to Frankfurt, and my father was desperate to come to the United States.

Prince: This was what time? About ’46 or something?

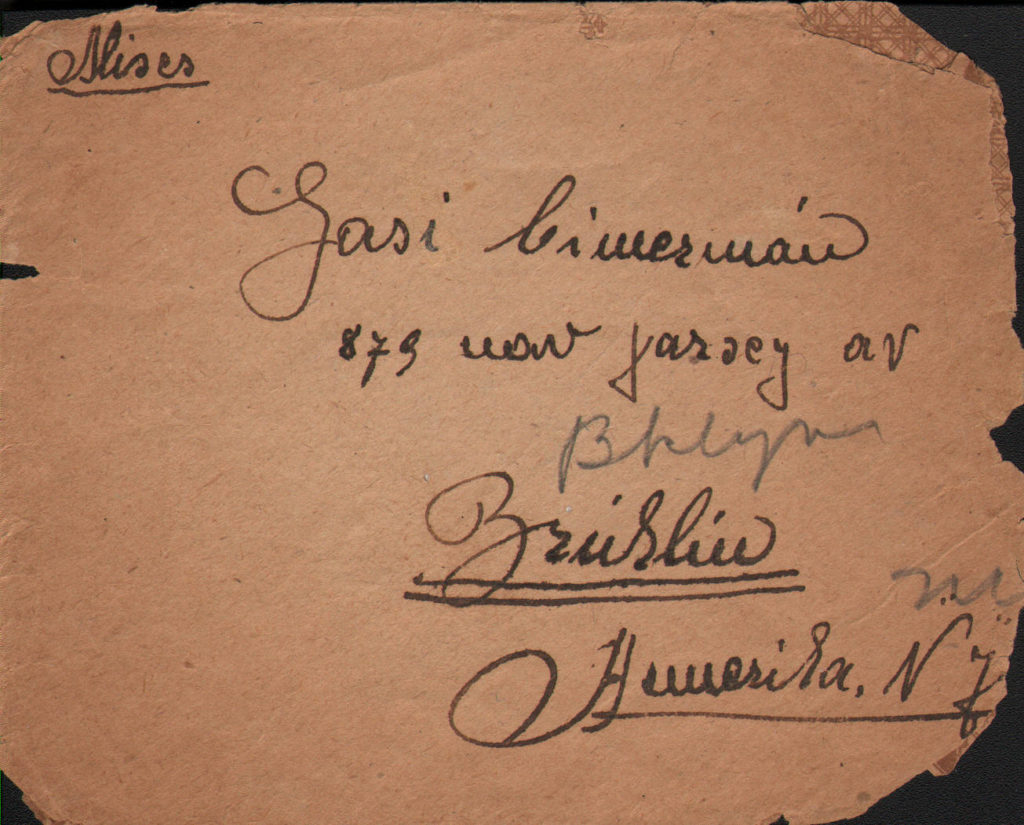

Jakob: This was end of ’46, ’47. We did some black marketeering, you know buying American cigarettes and coffee, and sell it to the Germans, and they would give their right arm for a pack of cigarettes, whatever they had they were so desperate to get a half a pound of coffee—they couldn’t even afford a pound of coffee, but a half a pound of coffee. So we would be the in-between guys. We would buy it from somebody that would bring it in from France or from Holland or from some other country. And then we would resell it. So, we would make a little money that way. And so my father was able to save up a few dollars. And all of a sudden he heard that there was a chance, a much better chance to immigrate to the United States from France. So he decided to go—to leave Frankfurt and go to France, and he was going to go from there to the United States—by that time he was remarried, he married this lady…was a very nice lady, I liked her a lot. He picked himself up, and they went to France.

Prince: Also a displaced person?

Jakob: Also a displaced person. Yes, she lost her husband, she lost her baby. And they got together, and they married in Frankfurt. So, they left—they asked me to come, and I didn’t want to go. Somehow I felt that it’s a sham, it’s not going to work because there were so many crooked deals going on, you know, everyone was promising everybody, you know, how you can go to the United States, how you can go here, how you can go there, but it was a money-making deal, you know, people were trying to make a fast buck. So, he, my father had a few thousand dollars saved up, and he—in those days, two thousand dollars was a fortune—and he left from Frankfurt, and he went to Paris, and he lived there, for about a year and a half they lived there in Paris. And we communicated by mail. And I kept asking him, “What’s happening? Are you going to be able to leave?” And nothing happened. After a year and a half they had to leave France—first somebody took his money and promising him he’s going to be able to emigrate, and nothing of that sort happened. And he came back to Germany. But by that time, Irving (Erwin?)and me, and this story I’m about to tell you…my family loves it. They like this story more than the story about the concentration camps. [LAUGHS]. So, Irving (Erwin?), and me, and two brothers—___?___ and Martin—and a German-Jewish guy, his name was Eisemann (?) was his last name, I don’t remember his first name anymore. But he was a butcher from before the war, and he survived the camp. But he was not a business man; if somebody helped him, he was ok to do things. And I don’t know how we came to this idea, all of a sudden we decided to…sell kosher meat because there was need for it.

Prince: Uh huh. In Frankfurt?

Jakob: In Frankfurt, yeah. So, first the four of us—the two brothers, Irving (Erwin?), and me, and we were just youngsters, you know, who were we, fifteen years old, sixteen years old—we decided that there is a need for kosher meat. People were interested in buying kosher meat again. So, we went to the German authorities and inquired if they would give us the proper documents and licensing that we needed to sell kosher meat—nobody said no. They saw who we were, where we came from, they agreed to everything. There was no questions asked, but it was a huge undertaking. Almost—you can’t even imagine…then we had to worry about a place, where we going to open a place? We found a place on ____?____, which was the name of the street, it was ____?_____, in Frankfurt, nice area of the city, but there was still everything bombed out. But before the war—you saw the pictures—it was a beautiful street. And we found this was actually a kosher butcher living in this place before the war. So, we went there, and we looked through it, and we found…the place was destroyed, the building was destroyed—it was a brick building. But we found the icebox that he used for the meat was still intact.

Prince: That’s like a dream.

Jakob: Yeah, it was still intact. When I say it was an icebox—it was literally an icebox—it had no motor, but he used to put blocks of ice in there, and they were selling, you know, that’s how they kept the meat cold.

Prince: This is very heavy—I mean, this is a very fantastic thing for you all, you’re creating something…

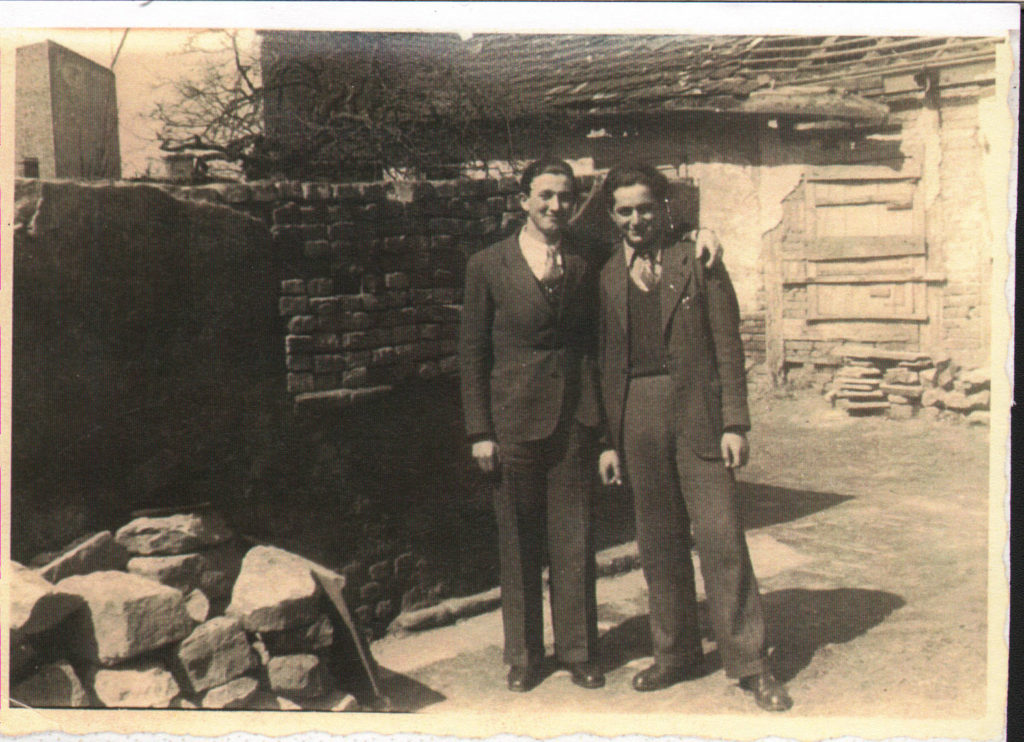

Jakob: Yes, yes. I’m amazed sometimes how we came up with this idea. This is what we talk about when we get together, you know we reminisce, you know, about these things. And…so the…so then we had to go back to the German authorities, and we explained to them that we found this place, but it’s not our place, and if the owner will ever come back, they can have it, but we would like to do something here in this place because it has an icebox, it was a Jewish place before, and we thought that this was the right place that we could start building and sell kosher meat. So, first, we had to build a building because there was no—the building was destroyed. So, we were bricklayers in Auschwitz, we knew how to lay bricks, and pretty soon we went to work, and we built a room big enough to…right in front, you know where the sidewalk was so we could display. But we didn’t realize that we didn’t need no display, we didn’t realize that. So, and this Jewish guy, this Eisemann, he went along with everything we wanted to do, he saw that we were go-getters, you know, we were not the people that just talk about it, we wanted to get things done. So, he just went along with it, we always said he just schlepped along. He didn’t want to believe this was going to materialize, but we said, “Just go with us, we’re not going to stop until it’s going to happen.”

Prince: And you were kids. Was he an old man?

Jakob: We were kids. He was older, yeah, he was probably twice our age, twice. So, it wasn’t long, everybody chipped in, we built this little building around the icebox, and when the building was up we went back to the German authorities again in the city hall. We told them, “Ok, we’ve got a place where we can sell kosher meat. Now we need a license to find the animals.”

Prince: You had a roof and everything?

Jakob: We had a roof on the building, yeah. So, we were not allowed to butcher there…that was not allowed, that has to be in the slaughterhouse. Then we had to have a _____?_____, do you know what a _____?_____ is? There was two of them that survived that camp in there. We approached them to tell them what we had in mind, and they agreed, you know, everything we need was available (?). Everything we had to take step-by-step, and we managed to get there. So, when everything was in place, and the Germans gave us permission to butcher one cow a week. They said, “Ok, we give you—” Because they themselves didn’t want to believe it, they see them young guys, they figured, “They don’t know what they’re talking about.” But they didn’t want to stand up, because they wanted to get along, and they agreed to it. So, they gave us permission to butcher one cow, and pretty soon, we took this guy Eisemann, and we went out to the country scouting by the farmers to find a cow to be butchered, and we found it, we paid for it, we brought it into the slaughter house, we called the ___?___, he came and slaughtered the cow according to Jewish law, and we brought it into the butcher shop—we had a start. And my father was still in Paris. And we were pinching ourselves, “Is this possible?” You know that we were able to do this, that we’re doing this. We brought the cow in—and at first we didn’t…you know, the front part of the cow is only kosher, the hind quarter is not kosher, I don’t know if you’re aware of that.

Prince: Yeah.

Jakob: Yeah. Only the front part of the cow you can sell to Jewish people as kosher meat.

Prince: From the waist…

Jakob: From the waist up. From the waist down is not kosher.

Prince: Oh, interesting.

Jakob: Yeah. We knew that—we learned that in Frankfurt, you know, in Hebrew school. So, we were able to separate that in the slaughter house, and we had no problem selling the hind quarter to other butchers who were not Jewish.

Prince: Were there any other Jewish butchers at that time?

Jakob: No.

Prince: You’re telling me that you all built this little place up where it had been before, in Frankfurt, and you are the first Jewish butchers.

Jakob: That’s right.

Prince: Wow.

Jakob: That’s right. And we brought the meat in, and word got around, didn’t have to protest nothing, but word got around that there’s kosher meat to be gotten. But again, there always was a catch. You couldn’t sell meat, you had to have coupons that you can only sell per person like, I believe it was, a half a pound.

Prince: Oh.

Jakob: Which was ok, too. At least, you know where we came from a half a pound of kosher meat was a big deal. So, ok, so we had to sell it according to German laws, so we did that, and that cow disappeared the first day it was—no trace of it, there was nothing left, it was sold out. And if you could picture when that the Germans saw that we were selling meat, somehow the word got out to the Gentile population, there was a line formed, maybe ten blocks long, they thought maybe that they’d be able to buy meat here because the Germans were starving. There was…this time the shoe was on the other foot, we had food to eat, they didn’t.

Prince: That’s an incredible story.

Jakob: Yeah.