My aunt worked in an insurance company and they had Hitler pictures up in the house also in the early ’30s. I mean, after ’33 or maybe ’34-’35. So they were very careful. I mean, we still saw each other in the homes, but they had to be very careful. My other uncle, my mother’s oldest brother, had lived in New York already since before World War I.

EIDELMAN: Well, were your cousins Nazis? You said they had a picture of Hitler up in their house?

VAMBERY: Their father put the picture up to, I guess, to appease his business partners, or whatever…his friends, so that when they came in, everything seemed okay.

EIDELMAN: When they talked to you, did they say anything about how you were being treated or did you tell them what was happening to you?

VAMBERY: No. Well they knew. My cousin, as a matter of fact, my cousin was in England with me for a whole year. Because at that time, 1934 to ’35, she is a year and a half older – she did not know whether or not she was going to be able to manage in Germany as a half-Jew. What would happen…whether she could or couldn’t. So she went to England with me at that time, but went back a year later. We both went back and returned initially just for vacations. And she stayed in Germany and had already, which is in my diary, said on occasions she was glad that people didn’t know that she had a Jewish mother…and therefore, didn’t know that she wasn’t pure…racially pure. And this is the cousin I visited. I don’t know if you want that now, but I have it. I visited in 1978…I visited several times in between in ’67, 78…35 years, 33 years after the liberation, and after the end of the Nazi terror. When I came to Germany I wanted to spend one more time seeing all my older relatives in Germany. My aunt was still living. She was almost 89 and died shortly after I was there. Her daughter, who I said was a year and a half older than I am, and I had never before…I had been there three times before, and had always stayed in a little hotel nearby. They had not invited me to stay in their house. They had a large house. So I wrote that I would only come this time if I could stay in their house with them. I would not otherwise visit anymore. So my aunt wrote immediately, “Yes, come.” And as soon as I came to Stuttgart, I was in Spain and England before, my cousin confronted me by saying, “Please don’t tell anyone who you are…why you left Germany. I have told our young girl, (they had an au pair girl from England – she was 18 years old) that you had married a G.I….an American G.I. and that’s why you went to America. And don’t tell them who your father was (My father would have had his 100th birthday this year). Nobody in Germany…in Stuttgart would have known him anymore anyway. And if you go to the store next door, don’t tell them who you are.” She gave me all these instructions. She had a room rented to somebody – not to tell this person that I was a refugee from Hitler and whatever. And I said, “Edith – it’s thirty three years after Hitler. You’re not living in Nazi Germany.” And she said, well of course this was all in German…she said, “It’s not a good idea for people to know even now.” And so you know that it hasn’t passed. The repercussion of whatever, or the Neo-Nazism is there and it’s forever…apparently. And so I stayed this week because mostly I really wanted to have some more contact with my aunt. And she played the piano for me and all that. She was my mother’s sister. We had been very close…the families…we had gone on vacations with each other and so on. So then I spent a week in Uln where the cousin, a woman who was married to a cousin of my mother’s, which she is not Jewish and she’s very much the opposite. As a matter of fact, she is 86 years old and is coming to this country to attend a Bar Mitzvah, although she is not Jewish at all. But she has a very different feeling. It was okay for all her relatives – her non-Jewish relatives to know who I was and to meet them. And then I went to Bad Reichen Hof for a week where my aunt and uncle who used to live, who fled to New York – well he did – are living in a retirement center because he felt he couldn’t manage in New York anymore. They are 88 and 86 now. And my uncle, who is my mother’s youngest brother, is still living now, had been in concentration camp and was able to get out because of his non-Jewish wife. She did go there to get him out with the stipulation that he leave Germany within 24 hours, which he did. And he went to England and then came from England to New York, where…I wanted to finish – that my uncle in New York had been the Chief…Editor-in-chief of the German newspaper, the New Yorker which he…became very Staats Zeitung – Nazi oriented, in ’36-’37. And in a way, fortunately for him, he developed Parkinson’s disease and was retired by the paper. Because they would not have kept him as an editor-in-chief although his children didn’t know that they were half Jewish. When we came in 1937, my cousins in New York, Erica and Eleanor, they were 14 and 12 and their mother was not – she was Swiss Protestant – had not been told that their father was Jewish. And this was the first experience they had with Jews or with they ever knew that their cousins were Jewish.

So that brought home to me, maybe you need to know who you are – what your identity is. I still don’t believe in any religious orientation. I think religion divides more than anything…divisive…but I do feel that you have to have some idea of your identity.

EIDELMAN: Getting back to Germany – you went to school in England. Then you came back. What type of discussions did your family have at home, at the table, whether or not you would leave and what would happen, and…?

VAMBERY: Yes, that is a good point. In 1934 when I left initially with my cousin to England and I was very leery about leaving, I really…I thought I might not see my parents again because things were not good…were pretty bad at that time. We realized it. I realized it and I think they did. And then when I came back in ’35, a year later, my father had pretty much lost his practice. Really he…people couldn’t come anymore. And they had rented a room by that time, in a house, to have some additional income. And we were then talking about the possibility of having to leave. My father was still resistant. My mother finally said, “I will leave this with Renate…with me.” She would not, because she felt absolute necessity for me to get out. And my sister was living away from home and then getting married. She got married in ’36 and moved to Frankfurt and her husband had already…before she met him…been on hakhshara. That means he had decided to go to Palestine. Hakhshara is where you train for a agriculture. And so Ruth, my sister, who had excommunicated herself at one time from the Jewish community in Stuttgart, had decided to go to study Hebrew, Ivrit, and go to Palestine. She obviously rejoined…or mean I don’t think there is such a thing, but it is printed in the community, Jewish community paper, that Ruth Leibman had “Ausgetretan,” that means she had excommunicated herself which was, I remember this very distinctly, it annoyed my father terribly. That, he did not want either. He didn’t want her to separate herself. I think she did it mostly to annoy him, and so she was 18 at the time. And it was…was in 1930 when she did that. And then she swung the other way after 1933 and decided…anyway that is how she met her husband. And they were not allowed to get out when we did because the police – Gestapo in Frankfurt – interpreted his being on hakhshara as being a Communist. And so they held his passport and they couldn’t leave for another year. They got out…just before the Kristallnight. So anyway, yes, it was very serious. I remember that there were, when we had people, like relatives or friends, there were only – maybe you didn’t have more than two or three people at a time in the house and all the blinds were drawn and you talked in a whisper. I remember that on the street car with my mother already in ’33 or maybe a little before then, we would not held a conversation anymore for fear of being misinterpreted or picked up…or whatever. So this was very early. The whole atmosphere was heavy and unpleasant. So I went back to England and for several months I became ill and after being treated there for a kidney infection, they sent me back home. And after that, I attended school. I went to Switzerland. But by that time, my mother was certainly convinced that she was going to leave and that we would have to leave, if we wanted to be safe. My father was getting calls at night. Apparently I was not there at the time – from former colleagues – not to show up in court and not to show up, you know, that he would be apprehended…be arrested. And so he had all kinds of frightening calls. And he still…somehow…he didn’t want to leave.

EIDELMAN: So was he still practicing law?

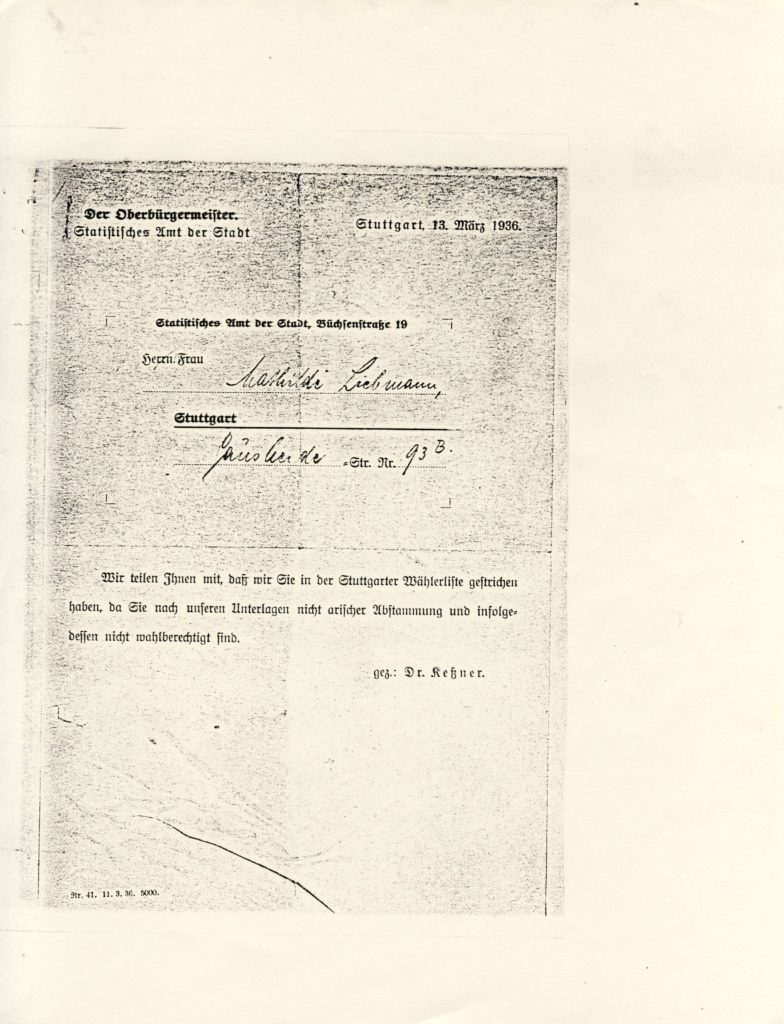

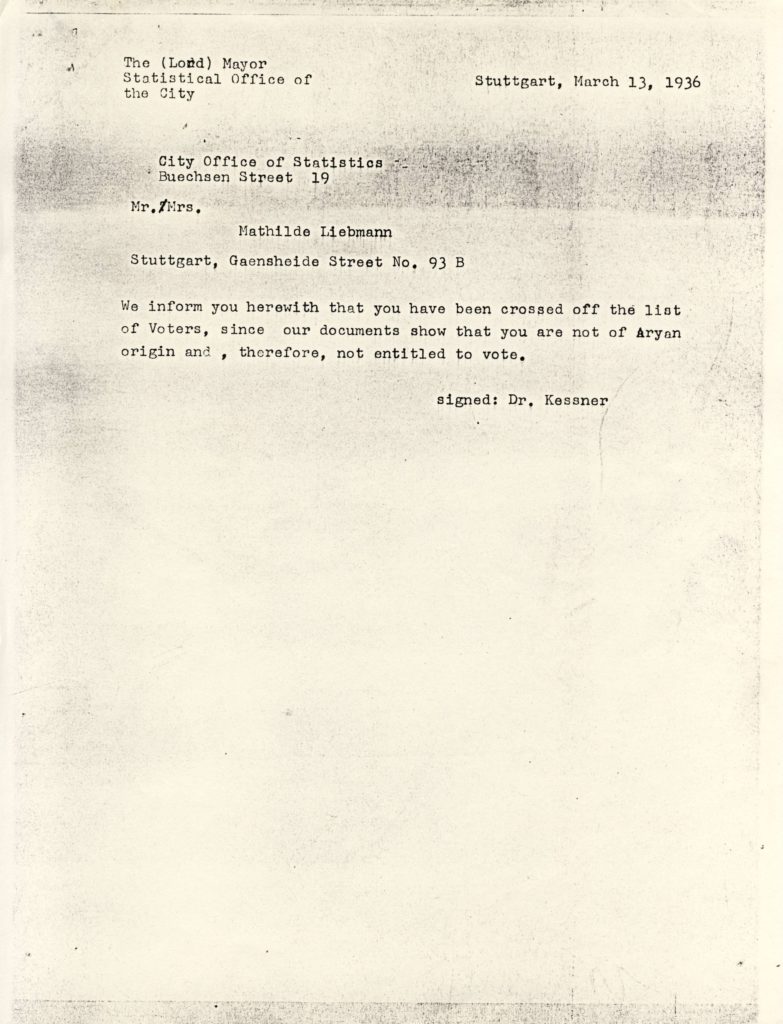

VAMBERY: For the few things that I show you, a letter in ’33, that he tried to get someone out of prison – a Jewish client. It was refused…was rejected. It’s in this book I have. He was still, I guess, practicing some, a few things that maybe he could practice. I really…it was practically down to nothing.

EIDELMAN: Was there not a Nuremberg law that eventually said that Jews could not practice law?

VAMBERY: That came, I think, that came the year we left in ’37. But you see, even without the law, after he was told not to show up in court anymore and all that, he really couldn’t practice anymore. But in spite of that, it was extremely difficult for him. Don’t forget, he was 55 when he left…and to leave – like all his books – his law books. He took me, the last few days before we left, when he finally decided we would leave, to his office and said, “What should I do with all these books?” And I said, “Well, I guess you have to leave them.” And for me, it didn’t seem that big a deal at that time. But for him, it was very, very hard and I only realized it much later when I got to that age. So anyway, it was his livelihood. He said, “What do I do – wash dishes?” And he had never washed a dish at home. So anyway, by the time I was in Switzerland… ’35, ’36 to ’37, they were convinced and they wrote. My mother did most of the writing, I think to the States and for affidavits, which came from our relatives here in St. Louis. These are my father’s relatives. My mother’s, as I said, her brother who was the editor of the German newspaper, was already very sick and didn’t have enough money to give us a good affidavit, so we did get it from our relatives here, and then decided that there was really no way out. We did have conversations during the time I was home, in between, in ’35 and ’36, about going to a South American country. My father would have preferred. Somehow I knew Spanish and French better than he did English. And he would have preferred that probably. And then some people went we knew, our friends…our relatives…were going to Australia or different places. But then since we did have a good affidavit, we decided to come to this country. And while we were packing, I was home for that…that week, that last week before we left – I finished in Switzerland. We had Gestapo there in the house…while we were packing…to see that we didn’t pack jewels, or money, whatever. And I remember my mother and I, burning all, before they came, burning…crying while we were doing it…burning all the books written by Russian authors because we knew that the Germans…these people…wouldn’t know the difference between Dostoevski and Gorky and Chekhov. And anything Russian would have been Communist and we wouldn’t be able to leave. And so we said… “It’s really better to do it that way – to get rid of all the Russian authors…Tolstoy…everything…and burn the books so that that wouldn’t keep us…hold us back from leaving.” So that’s what we did. And I have the German classics that they allowed us to take out…Goethe and Schiller and so on.

And so anyway, the times were very, very bad and I know my mother particularly suffered extreme, really extreme pain, because of her sister, brother and all of the people…all the relatives they had been very close…that were, you know, half Jewish. And she didn’t want to leave and then this aunt, my mother’s sister, who was married to opthamologist – they had a son in China and they could have gone to China and they didn’t go. They felt, you know, it couldn’t happen to them either. And they were eventually exterminated in Theresienstadt. He died of starvation, I heard, and my aunt died with a broken hip. She was supposed to march with a broken hip. I mean, it was miserable. We had the report later. And they could have gotten out, but so as a lot of others – they didn’t. They felt, you know, the Germans couldn’t do that to them. But the signs were there, and God, but the thing is when I’ve talked to them…when we went to this school in St. Charles, and they said, “Why didn’t everybody leave?” You know, when I told the kids I couldn’t go to school any more and I said… “Well, how would you feel if you couldn’t go to school?” And they said, “Oh, that would be fine. I would love that.” And I said, “Yeah for a little while you’d love it, but if you couldn’t, you know.” And then they said, “Why didn’t everybody leave?” And I said, “Okay, where would you go tomorrow if you were told you can’t live here. Do you know where you would go?” And then, of course, nobody knew.

EIDELMAN: Did you ever see Hitler in person?

VAMBERY: I didn’t, no. I don’t think I saw Hitler in person. However, I had to march with my school – I guess it was in 1933 – to see Baldur von Schirach. He was the youth leader and we had to march and stand in the rain for three hours. And at that time, we had to give the Hitler salute and shortly after that, it said Jewish students or children cannot, no longer, give the Hitler salute. So, yes, you would immediately be able to pick out. However, I still had to march with the school down to the center of town where he was speaking and listen to him. All the school children – the whole town – had to be there to listen to him. And Hitler, in person, no – he was there, but we didn’t go to hear him. But it was a very frightening atmosphere and even when I think about it…even in your own house, you know, if you think, you better lock the doors…close the blinds…and whisper in your own house. That was from 1933 on.

EIDELMAN: Did your friends in school threaten you or say any unpleasant things, or did they just say nothing?

VAMBERY: No – they did say nasty things about…once when we brought our lunch to school…and I had a banana or whatever, they said, “Only Jews would have the money to buy a banana.” They said something like that which wasn’t true. It wasn’t all that true at all. I mean, others ate it too, and they were making pretty nasty remarks – comments about Jews. Most of the time, I mean, after they had to…decided, you see…that they had to get rid of me somehow, that they had to…that they couldn’t keep up their friendship. There were a couple of kids in school – one of them I did try to find her when I came back. I couldn’t find her because she was probably married under another name or moved away, had sent flowers to the boat when we left…for me. But that took courage to do that. But it…I had no personal contact with them anymore.

EIDELMAN: How were you affected by the fact that Jews couldn’t go to public places or movie theatres?

VAMBERY: I didn’t go to movies very much in Germany. You couldn’t go to movies under 16 so I would…have just really started going to movies…only to educational. The swimming pool, because we used to go there a lot in summer. That affected us, my sister and myself, very much. And the public places felt very restricted and very discriminated against because you could not go to most restaurants anymore. It is not that we went out that much, but the fact that you couldn’t – that you were not allowed to go to most of the public places – that you were afraid wherever you went, that you were going to be apprehended.

EIDELMAN: Did you have to wear a star at that time?

VAMBERY: Not at that time, no. That came later. That came in ’38.

EIDELMAN: Did you try to go places where the sign said that Jews were forbidden – that you figured that no one would know who you were?

VAMBERY: No, no, I didn’t. I wouldn’t and I’m sure my parents didn’t. They were much too law-abiding. (CHUCKLES) I do know that my friend – I have a friend who’s living partly in England and partly in Florida – he lived in Mainz…a different…another community…and he said he still went with some of his non-Jewish friends. He would still go places because apparently the atmosphere was very different. That he would still go and just pay no attention to the signs. But I didn’t and my family didn’t. (LONG SILENCE)

EIDELMAN: When you were in gym class in school, did the children treat you in any way different from the non-Jewish children?

VAMBERY: In gym, or you mean…before ’33?

EIDELMAN: Let’s say before ’33 and how they treated you after ’33.

VAMBERY: No, not particularly in gym. I don’t think so.

EIDELMN: Or let’s just say, in general. What I am asking is…did you feel much anti-Semitism before Hitler came to power? Were you aware that people were anti-Semitic, let’s say, between 1920 and 1928?

VAMBERY: Right. I started school in 1923. I was in nursery school, kindergarten before then. No – there was an incident in grammar school. It was probably the second or third grade. As I said, I was always first in class. I was reading long before I went to school and I had really no problems. Anyway, I was accused by a teacher of cheating on a test…of looking up something or other while we were taking a test…I think. One of the girls in class said she saw me cheating. First of all, I didn’t need to cheat. I knew my material. Secondly, I would never have done it. I was brought up in a very law abiding family. Since my father was a lawyer and we always had to really go by the book and observe the law and be honest at all times. And so it wound never have occurred to me. Anyway, she did…this girl apparently – she told the teacher that I had looked up something in order to complete the test. And the teacher then, I am sure now, and I was sure much later – that it was an anti-Semitic thing that I had to defend myself…and I was in tears and that they interpreted as being guilty, you see, by bursting into tears. And I had to go to the principal and eventually it ended up my parents going to school. Of course, you see, in the mid 20s, there was a strong Weimar Republic and a strong civil rights, you know, kind of things, civil liberties. And my father went to school and eventually it seemed to…this was then ironed out. But I changed schools after that – after the year was over. I’m pretty sure…I’m convinced now…that it was an anti-Semitic thing.

EIDELMAN: At the time did you feel that it was?

VAMBERY: I wasn’t…I didn’t identify that much that to really be able to…

EIDELMAN: I see.

VAMBERY: I think my parents felt that way. I was maybe eight or nine that I wasn’t that sure that that’s what it was. But later convinced because it was really…part of the thing was probably jealousy. Because as I said, this other Jewish girl who was in my class for a while and I were always ahead – the two of us were always…took the first two places in school.

EIDELMAN: Would you say that as you were growing up before Hitler came into power – that you were not really aware that there was any anti-Semitic feeling in Germany?

VAMBERY: Except for these isolated incidents – I was not that aware, no. I became only in 1930 aware of that.

EIDELMAN: Do you have an opinion as to how much anti-Semitism there was in Germany before Hitler came in, compared to how it is in the United States now?

VAMBERY: Yes, I see some real similarities because I see the economy in a very similar situation. I see the unemployment very…

EIDELMAN: I was thinking more of peoples’ views as opposed to the economic situation.

VAMBERY: Yes, I think…I don’t think Americans are very different from the way Germans were. I think when things go bad, they blame it on Jews. And you hear them say, when a Jew does something that is negative, he is called a kike. There was a column in the paper last night by Bob Greene on that…that immediately is a derogatory term used. So I see that it could happen here. And that is why I am very concerned that we alert young people particularly to that. I mentioned – I think that I went through almost four years of psychoanalysis and I think I had it so repressed at that time that I don’t think I ever talked about it. But I think I do see similarities in…in attitudes here too.

EIDELMAN: What specific things did you repress that have now come out?

VAMBERY: I had repressed, seems to me…that while…all the things that came out later in my diaries and so on…that had gone on in my life and we got to Hitler…I dealt mostly with my relationships with my father. And in analysis, that is what you do. And I may have mentioned something, for instance, that I had a non-Jewish boyfriend whose mother asked me not to see him again. That was another thing. He was my first real boyfriend and was not Jewish. And he was very much in love with me. And his mother came to the house and asked my mother to tell me…I met her then…not to see – either come to their house or to have him come to my house…or be seen with him anywhere…anymore. So I did. He didn’t really ask…she did, his mother. And so, although he did write some letters later and did…wanted to go to Italy with me, but at that time, I wasn’t that interested in marrying him. I don’t know, it seemed so far away. I seemed to have a lot of other problems and other things that I wanted to get straightened out first before settling down – and so I didn’t.

EIDELMAN: How has being through the experience in Germany changed your life or affected you?

VAMBERY: Well I thought about that the other day. I talked with some of my friends who are native Americans and I said, you know, I mentioned that it really ruined my adolescence, actually most of my adolescence, when other kids here have a lot of fun and I had to leave home then and go to England and Switzerland which doesn’t sound bad to most people…except that I didn’t know if I would ever see my parents again or what was going to happen. I went under pressure. I didn’t go because I wanted to study at the Sorbonne. It was a different thing. So I feel it ruined my adolescence. I think it has affected my relationships with people, in general, in spite of all the analysis I had which was helpful to some extent, in not really trusting people very much because right now, with crime and so on, I have been cautious about that. But I think it affected and I believe I did that for most most people I know…the relationships with people in general. Since you know, whatever, the years from the time I was 14, 15, to the time I came here, 20, and then I had to work very hard here in order to go to school which was very important to me. So I had another three or four years when I had very little social life because I concentrated all on education and work. And so I think it took at least five or six years out of my life.