PRINCE: Okay, you’re at the _____ and you’re crossing the…

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, we saw before the main crossing, we saw this. Oh, and he was prepared, he knew the Russians, he had a bottle of vodka, you know, and there was a… a few trucks, military trucks, going that way. And he put – you wouldn’t believe it – I knew a little, you know, how to speak Russian, but he – he didn’t and he took the vodka and just put it in the – on the road. And they saw him do it and they stopped, they took the bottle of vodka. (LAUGHTER – CLEARS THROAT) Excuse me. And, they – they let us in the back. It was a closed-in truck and it was, it was, um, not cans, but barrels of – I don’t know if it was gasoline or some kind of oil. And it was so smelly I couldn’t breathe, you know I was choking. And he said, “You be very quiet, all of you, and when I get stopped by a checkpoint don’t say anything. Be quiet.” And that’s how it was. They took us to the border. Then, we had to go to overcome one more obstacle, the main checkpoint. All the, you know, French, English, and American and Russian were standing before the German border.

Oh, by the way, before we went I recall, before we went to this, you know, area, there was in Czechoslovakia, there was one Jewish man. We had to stay one night there –

PRINCE: You went from Poland to Czechoslovakia, then into Germany?

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, there was one Jewish man, that he owned a lot of hotels before the war, you know the hotels were still standing. So he let, he was so good; he let all the survivors, all the displaced persons, not only Jews, anybody, anyplace, what help. You could sleep for the night, okay? And you didn’t have to pay him. So that was really nice; everybody was very impressed, you know. I, to this day, I feel _____, I really don’t. I – I was, it was so much excitement, and so much going on, that I failed to write down, I should have, you know, uh –

PRINCE: Dizzy to make a (OVERTALK) –

GUTTERMAN: – write down, everything, every paper… yeah, I just didn’t.

PRINCE: It sounds as though you were, almost in a, a dream – a dream trance.

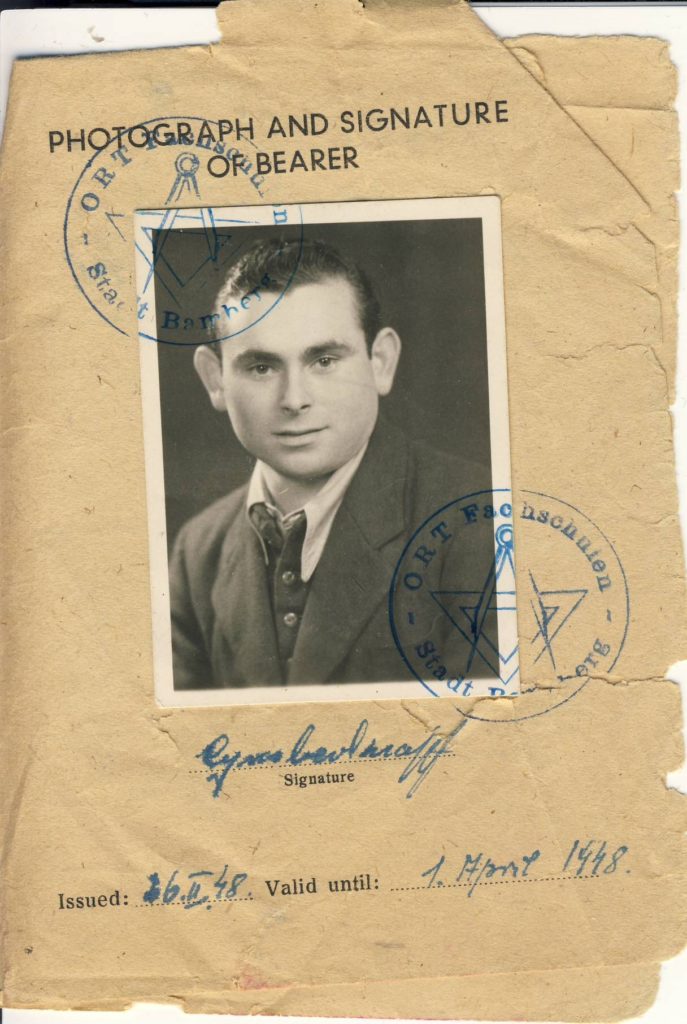

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, right, right. Just – I still was in a trance, what was happening to me, you know. And, just thinking back, it was just like on some – we’re on a dream journey, you know, going, not knowing who – where am I gonna end up, what am I going to do, what’s gonna happen to me, what is my fate? You know, I didn’t know. So when we came to the border, everybody stopped us, you know, and there was a train going into Germany, okay? I was shaking in my boots because – so, everybody showed passports, okay? My sister-in-law, that was later, my sister-in-law, yeah –

PRINCE: Yeah (LAUGHTER) I – I…didn’t want to ask.

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, you know, this man’s sister, she shows them their passports, they gone through, but they weren’t passports, they were fakes. I showed this. They didn’t know the difference. They looked at it, my picture was on it. That was a passport. They let me go. Oh, I was relieved. We went on that…

PRINCE: So you passed through all four… of these…?

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, we passed through all the points so far, you know. Because one, the very critical, was the Russians, helped us, okay? Just for the bottle, would you believe it? And I think it was hard to get maybe that time, or something.

PRINCE: Oh sure.

GUTTERMAN: And they –

PRINCE: Probably stole it, after the war – (OVERTALK) Stolen from the Russians and give it back to the…? (LAUGHTER, OVERTALK)

GUTTERMAN: Probably, probably, I don’t know, I don’t what he did, how he got it. But anyway, I guess he knew, because he went back and forth and back so many times to get people out. Okay, so on the train, I didn’t know Czechoslovakian, but I knew Polish and Russian and there was nice ladies. You know, by that time, we were presentable. We were cleaned up, so they didn’t know, there wasn’t…but I guess they sensed it, you know, people sensed it. So one lady came up –

PRINCE: Do you think they sensed it, Toby, or do you think they were just busy trying to survive themselves, because they too…

GUTTERMAN: Maybe, but I don’t know. I don’t think survival was with the cake, because that’s the first time since when I went to camp ‘till, you know, after the war, that I-I tasted a piece of cake. This one lady, a nice lady, took out, and she offered me a piece of cake. Can you imagine, that after so many years, I mean, my gosh. (LAUGHTER) I – you know, and I thanked her. And I knew the word in Czechoslovakian, thank you, then. (LONG PAUSE)

Yes, and we went finally to Germany and I found, I found out that I have no place to go, nowhere to live, no money. So, at first the man who took us through the border, his sister said, “Well, he got an apartment,” and she says, “You want to stay with us until you find something?” And I said, “Oh, how nice. That’s just wonderful.” And she let me stay with her, okay? So I said, “But I don’t have any money, what are you going, you know, I cannot share the rent with you or anything.” She says, “I know, my brother told me.” So, I said, “Okay, because I don’t want to mislead you. If you need someone to help you pay, I can’t, okay?” So she didn’t have much either, but her brother knew a lot of farmers and he was bringing, you wouldn’t believe it. He, he knew farmers, He could, he used to buy – he lived somewhere else, okay, in an apartment – he used to buy like, half a cow from a farmer, sold part of the meat, had the money and our meat around which – his sister, his sister was the cook for the whole family. In her house, you know, her brother and her other brother, who brought the girlfriend for – everybody was eating at his sister’s house. She was the cook. He brought, you know, her younger brother who took the people over the border, he brought food – he brought meat, one time he brought a goose, and everything. He went to the, what do you call it – to the officials, German officials. He registered us, all of us, to – as a survivor. He gave us special passes. And we were entitled to get rations, you see.

PRINCE: What part of Germany were you in?

GUTTERMAN: I was in Bamberg, Germany, that was Bavaria called in German.

PRINCE: Do you know how to spell it…Bamberg?

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, B A M B E R G. Bamberg, Germany. And he, uh, you know, he gave us those passes and we got a lot of – he knew people, they called it in German, beamte, you know, where the special officers were, and he got extra rations and things. And it was just unbelievable. Now her sister – his sister was lucky because her – she survived and her husband survived. She was married before the war. So, you know, they both survived. So he got a lot of things for his brother and sister and everybody, you know. So he was very helpful and that’s how I got through the first part of, you know. And then he started; he kept on asking me out. And his sister, when that was happening, didn’t like it too much.

Oh, I forgot. Also, you have to remember, I have a bad – I had a bad arm, you know, from the, I can recall that beastly, when I started telling you, no, when I started telling you when we were crossing, I’m going back a little bit. When I came to Germany, my arm was in a mess. It was hurting. It was full of pus. I had, you know, I had to go to a doctor to get, you know, I had surgery, okay. I don’t recall if I told you, I had surgery also in Poland after the war. A Russian doctor did surgery on me, but yet my arm didn’t get better when I went to Germany, because I didn’t have any medical care right after it happened. So it really got infected, okay? So what happened when I came to Germany, and his sister, this man’s sister saw that he’s interested in me, she didn’t like it. She – he told me that. And she said, “Why you wanna – she’s a nice girl, but you don’t know that much about her, and she’s sick. She’s got a bad arm. What if she never can use this arm? Who’s gonna cook for you?” You know, European people. “Who’s gonna do anything for you? Why you want – there’s so many pretty girls.” And you know, he was pretty good-looking. “Why you wanna, you know, get involved with this girl?” And he came and told me that. Would you believe it?

Well, one thing led on to the other, and he started getting serious with me. And he was very nice to me. All through the time, he didn’t take advantage of me. And that’s what I liked about him. I said, “Well I don’t know, I-” and his brother had his girlfriend, and he wanted to get married before his brother and his brother was older than him. He was the youngest. I said, “Why don’t you wait ’til your brother get married?” You know, his sister was married already. I said, “I wanna wait, because I don’t even know you that well. I know you’re nice, but I wanna wait.” So I didn’t want to get married right away. I was scared, you know, because I didn’t know him. And then I found out that his sister didn’t want him to be involved with me, so I just thought, “I’d better take my time.” You know, and then I found out his brother was trying to fix him up with another girl too, a very pretty girl, and she didn’t have no problems.

PRINCE: She had a good arm?

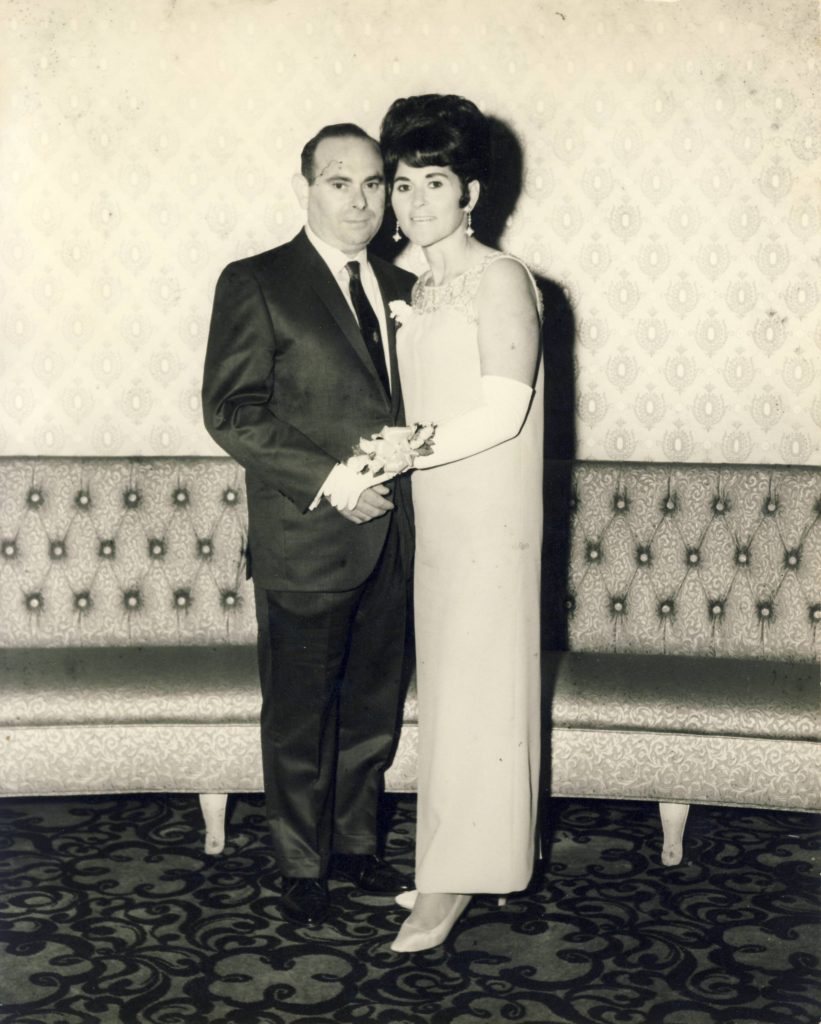

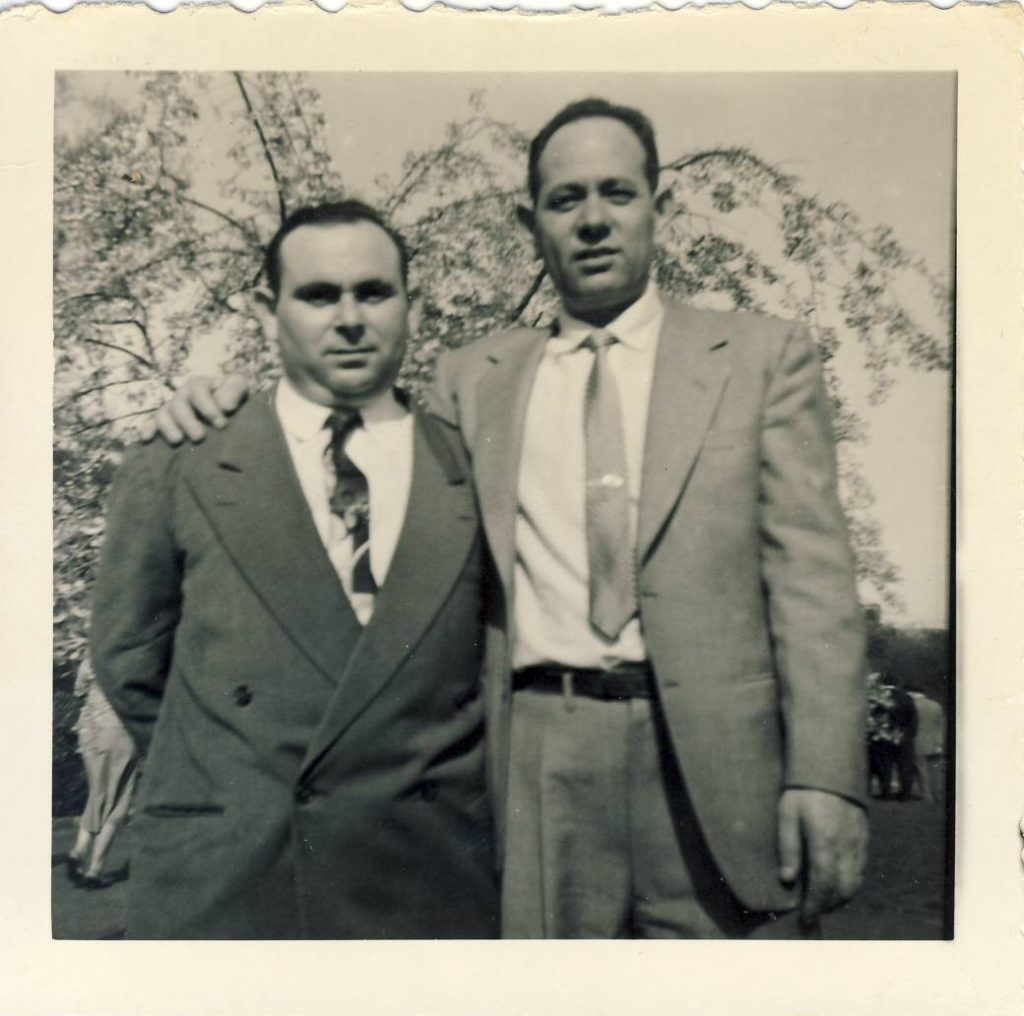

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, yeah. So, but, he stuck to me, you know, so, after his brother got married the following year, I think it was in July, but, uh, then we got married later.

PRINCE: Now let’s give him a name, Toby, because we’ve never given him…

GUTTERMAN: (LAUGHTER) Yeah,that was my first husband.

PRINCE: And his name was…

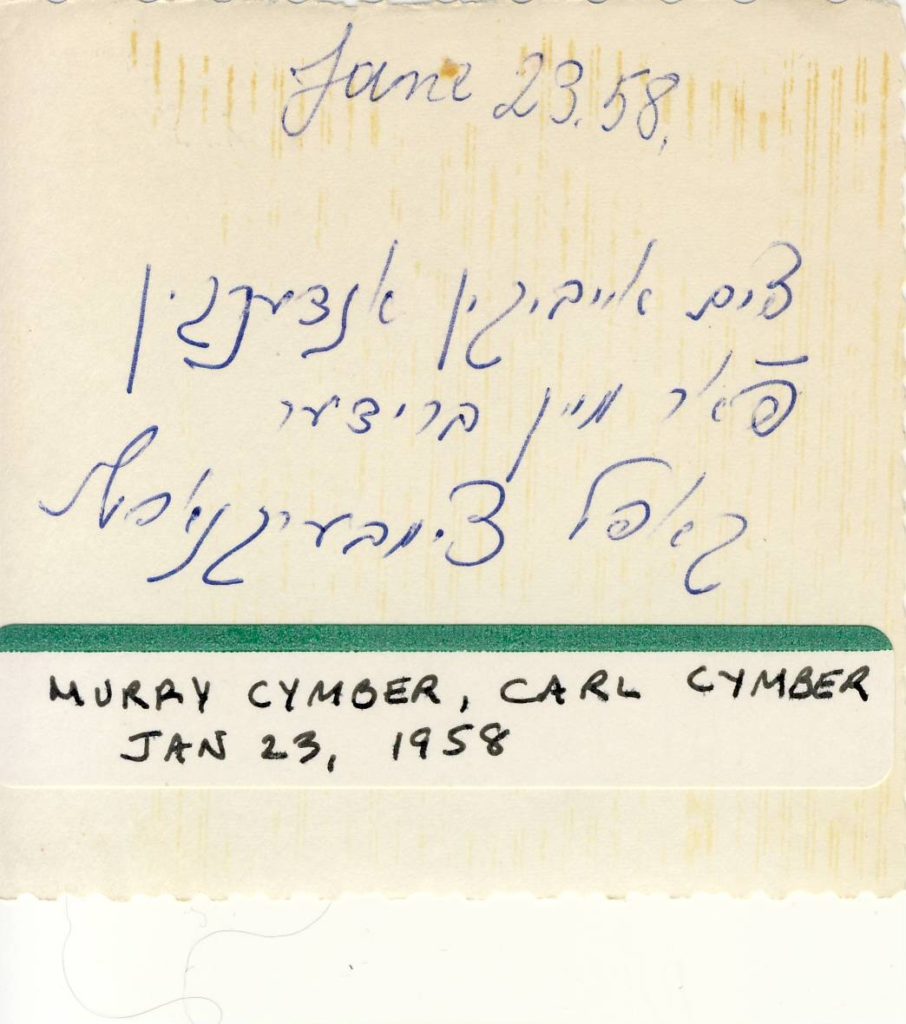

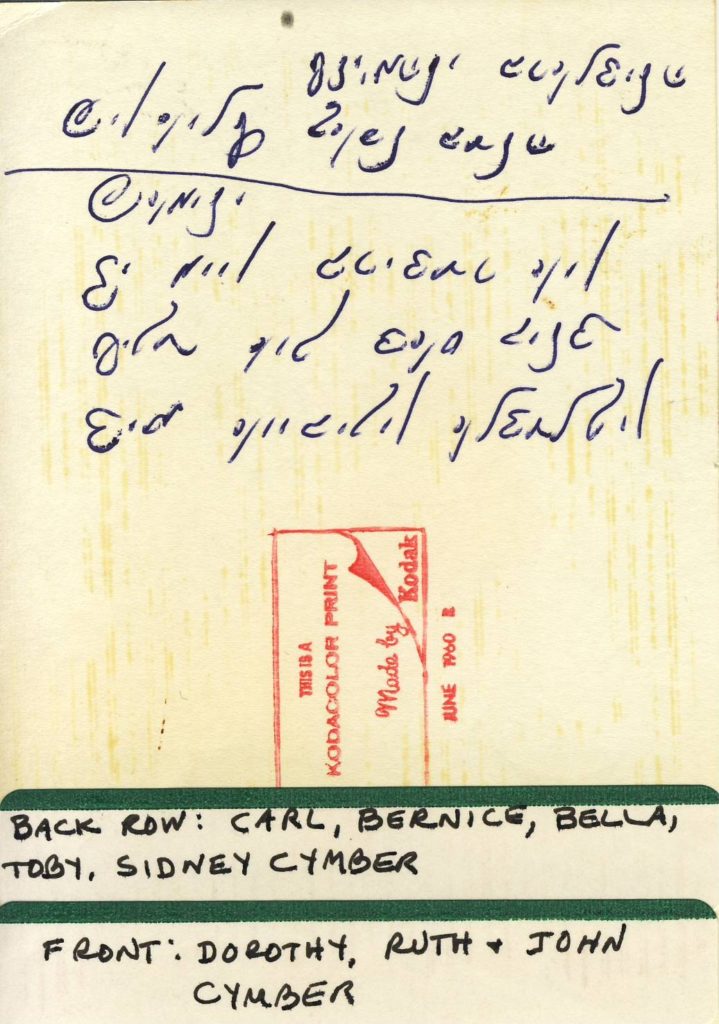

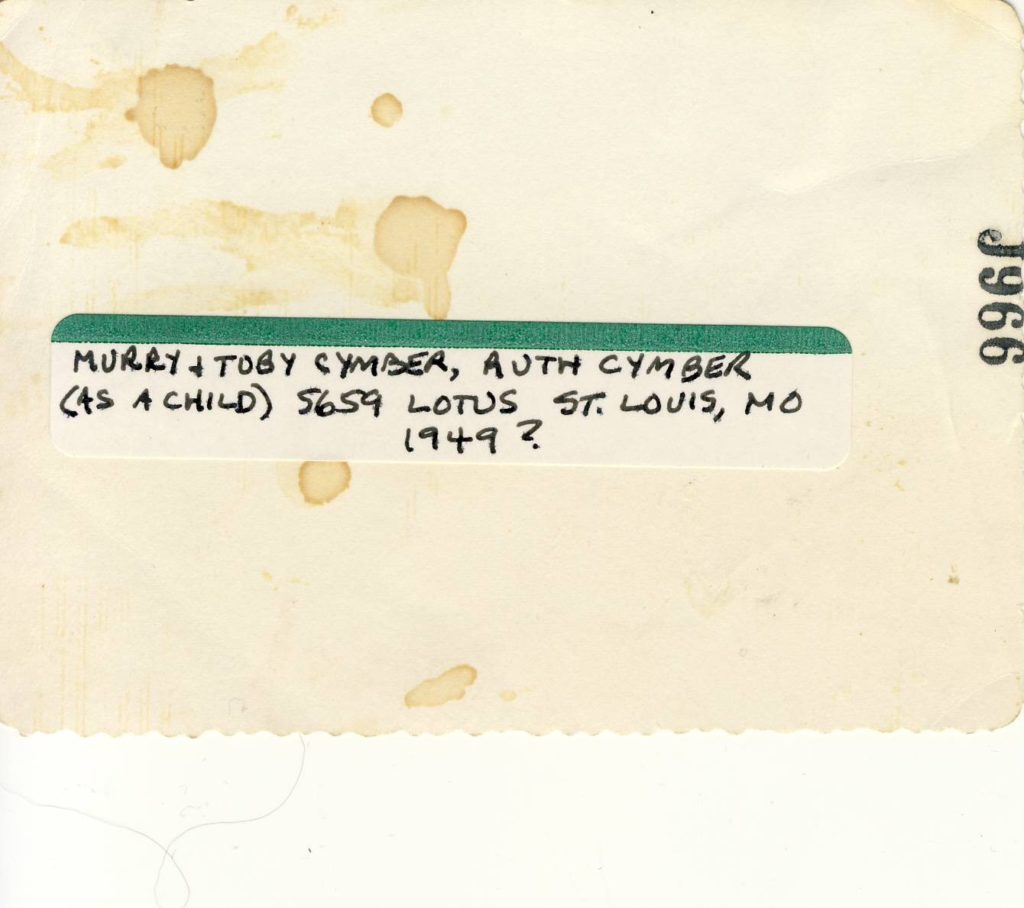

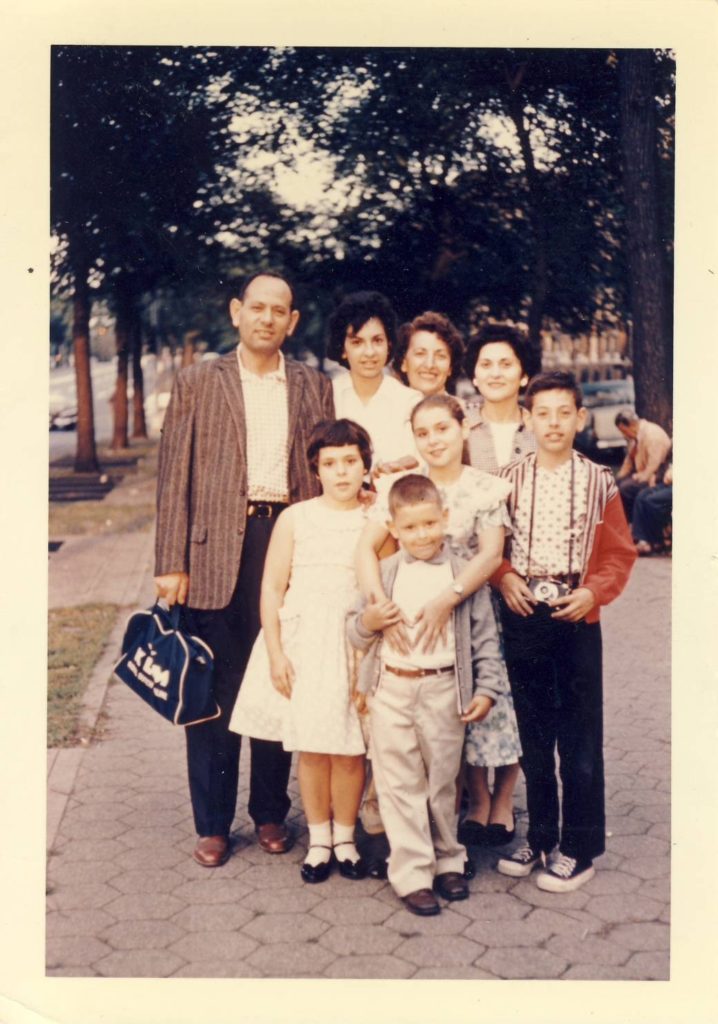

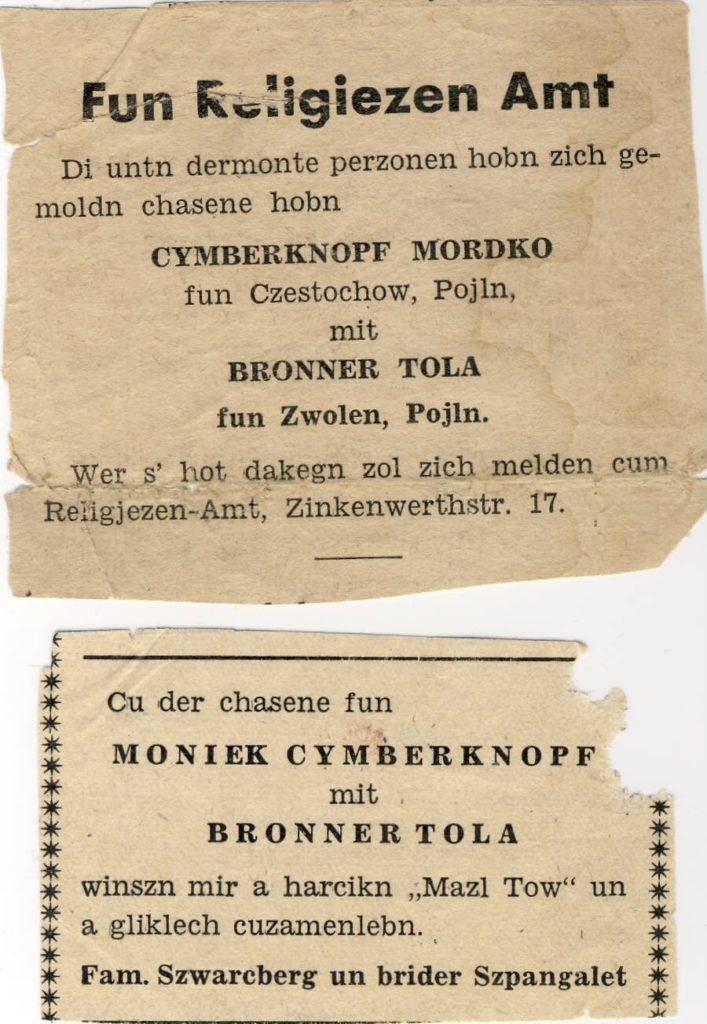

GUTTERMAN: His name was Murry – M U R R Y – and his last name was Cymber – C Y M B E R. He had a longer name, but he shortened it. That came later. When we came to the United States…

PRINCE: Do you know, I know a little of your background and I know about you, and I know you were married before you were married to Morris, and –

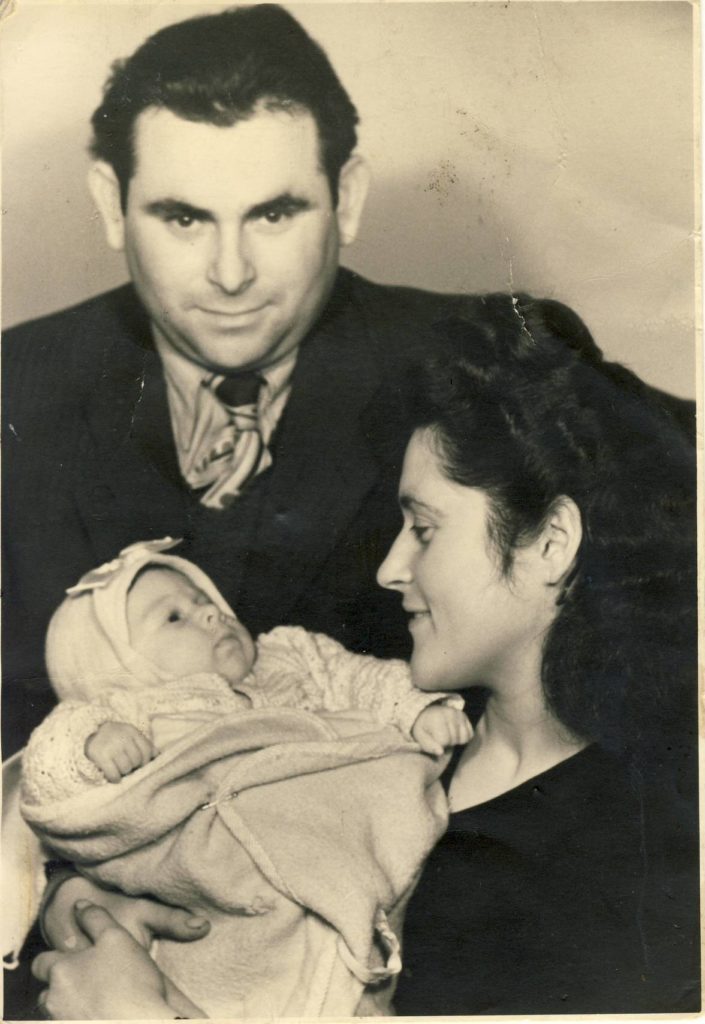

GUTTERMAN: And he’s the father of my children.

PRINCE: Right, and I knew, just knowing you, as soon as you started talking about this man, that that’s who it was.

GUTTERMAN: Oh, really?

PRINCE: Yes, ’cause I could tell –

GUTTERMAN: At first I didn’t know…

PRINCE: I could tell by the expression on your face. I just didn’t…

GUTTERMAN: And that’s why I slipped out my sister-in-law. Because she still might…

PRINCE: But they already, they already said…(INAUDIBLE) So you really never dated anybody else?

GUTTERMAN: No, I really didn’t. Well, someone else was interested in me. But I don’t know, I didn’t care for him, you know. And he wanted to – he was too pushy – he wanted to get married right away and I hardly knew him. And that’s already he was talking about, “Oh, I’m sure you a good cook,” and, you know, I had the impression he wants a good cook, or something. See, but my husband to be didn’t do that, you see. I felt like he was my protector. And if it wouldn’t be for him, I wouldn’t be in Germany. And when I look, when I look back then he, I tell myself, “Oh my gosh, I’m so lucky. How would I ever get out of Poland?” Because when I wanted to get a letter or something that I worked in a hospital, you know, maybe not in a professional position, but just in case if I wanted to work in Germany. But when the Russians heard that I’m going to the American sector of Germany, they just despised me! I mean, they didn’t want to have nothing to do. And they, they called me a capitalist, you’re going to a capitalist thing. I said, “Oh my God. Am I lucky that I came,” because really after that, shortly after that, no one, but no one could get out of Germany. I mean, I’m sorry, of Poland.

PRINCE: (OVERTALK)…it would have been the Hungarian…

GUTTERMAN: Yes, right, into Germany. You know, but…

PRINCE: And we wouldn’t be sitting here.

GUTTERMAN: Right, and I realized…

PRINCE: And we’re in 194 – 48…

GUTTERMAN: That’s’46, well, I was married in 1946.

PRINCE: 1946?

GUTTERMAN: Right, a year later. Yeah.

PRINCE: A year later. So we’re in 1946, in Bavaria…

GUTTERMAN: Right, and I was married in Germany, his – my husband’s sister, she’d, we – I’ll never forget it. Usually when you were married after the war, you didn’t have much of a wedding, okay. He rented a hall in a German place. He had an orchestra. We had, um, people in – a lot of people invited – he had a lot of friends, Jews and non-Jews, we had a nice meal there. His sister did all – she’s a good cook. She did all the baking, as far as pastries concerned.

PRINCE: She began to…

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, yeah. She couldn’t – I think a lot of it she, she hated for him to get married because he, he practically supported her.

PRINCE: I don’t think she was jealous…

GUTTERMAN: He brought everything to her home, food and other things, and he, you know, and he worked part-time, and he brought money to her ’cause she did the cooking, she was, you know, so she didn’t like him. She knew, once he get married, he’s not gonna bring as much, you know, support, the material things to her.

PRINCE: What did you wear?

GUTTERMAN: Well, I rented a white gown. Would you believe it? I rented a gown and you’re not gonna believe it. We didn’t have no cars, none of us, okay. And when we went from our apartment, my apartment, to – right around, I had an apartment, I didn’t live with his sister. Because when I found out she didn’t like me, I didn’t live with his sister. Now I was getting help from the government then to – with rations and to help me pay the rent.

PRINCE: I see. Could you – you could call that reparations?

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, well a little – somewhat. Not for long, but then, in the beginning. So I could get my own and I lived with a German lady, and she gave me a beautiful room. It had a piano, and she says, “If you want to, I’ll teach you how to play piano.” It was a beautiful room. And the German people, after the war, they were – they needed, you know, some extra money ’cause their men were killed in the war, or something. Her husband was gone, was killed. So I was there, you know, living there with this lady. And my own room and I – I used, you know, her kitchen, but I just was like a boarder, a boarder.

PRINCE: When the Germans – did the fact that what had happened and been done to the Jews, was that just not talked about? Was it just a vacuum?

GUTTERMAN: Um, after the war they were very, very pleasant, the Germans. But they, they wanted you to live like this because, first of all, if a Jew lived in a German home, they weren’t as suspicious that they found something, you know. And maybe they didn’t, they didn’t do it ’cause the lady was very nice…

PRINCE: But there was not totally distressed…(OVERTALK)…like it parachuted in from heaven or something…

GUTTERMAN: No, no, really we didn’t, we didn’t. No, we were pleasant to each other. To my lady, and you know…

PRINCE: But like you come from Pittsburgh or something…

GUTTERMAN: Yeah, yeah.

PRINCE: Okay.

GUTTERMAN: That’s just like that. And, I’ll tell you, that time, we didn’t get a lot of gifts, maybe a little scarf or something, you know, flowers. Everybody sent flowers. I mean the room was filled with – from ceiling to bottom with flowers, you know. (CHUCKLES) And, uh, a rabbi married us, you know, and like I said, it was –

PRINCE: A survivor rabbi?

GUTTERMAN: A survivor, but he’s dead. I don’t know, he had surgery. I think his wife is still alive. He had surgery one time and what happened, they gave him to drink some juice or something and the can – it was from a can and it was contaminated. It was a big – oh, it was a big scandal. And he died from it. (PAUSE) After that we lived in Germany until 1949. We waited until we were going to be registered to go to Israel or United States, whichever comes first. And we got a call from, a letter from the United States Government that we can go, so in 1949 we immigrated to the United States.

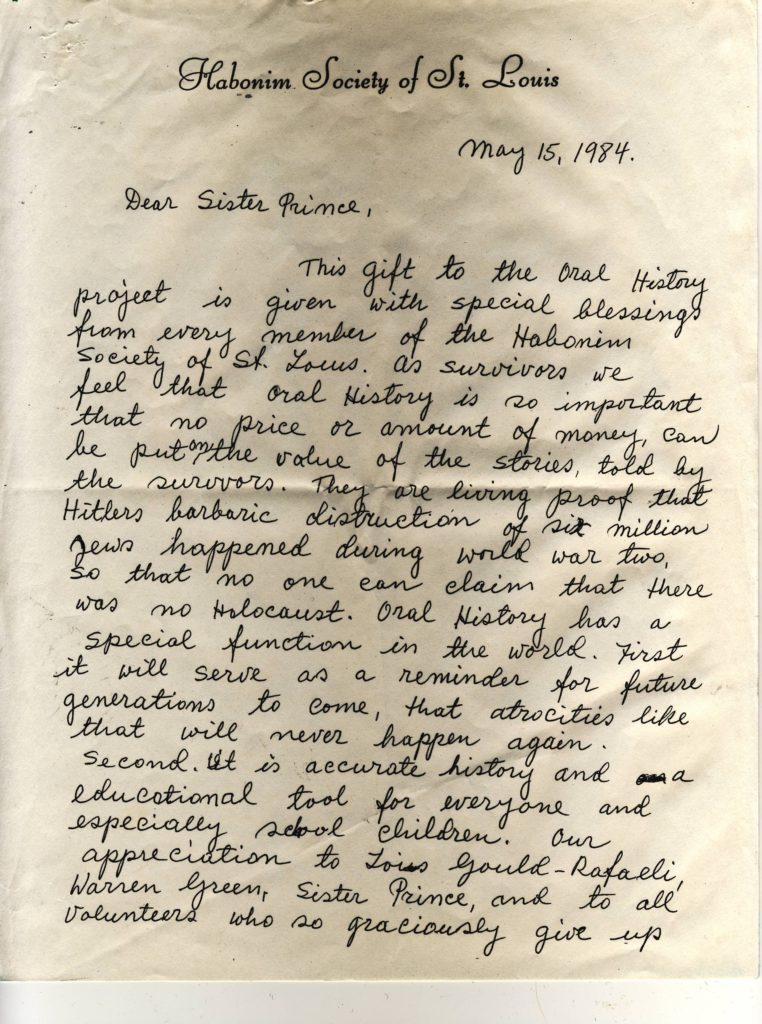

PRINCE: Toby, thank you very much for all the work and effort and time that you gave to us.