YOUNG: Basically, what I would like you to tell is your own story, and we usually start with where you grew up and about your own family.

BURGER: You want family background to begin with.

YOUNG: Yes.

BURGER: We have two situations here. My grandparents on my father’s side came from Poland. They immigrated before the turn of the century. It was a World War I immigration. They came to Vienna and had all their children there, nine of them. They were poor and they had a hard time making it. They were Orthodox and when the last kid was born – the last two were twins, as a matter of fact, a girl and a boy – my grandfather decided there was no future there and he applied to come to America. There were cousins all over the place here, in the Detroit area. And in those days, of course, there were no affidavits. He came in, landed in New York, got pneumonia and died. He is buried in New York. He never achieved what he wanted to, to bring the family over. So, my grandmother was stuck with the nine kids, raised them until they finally either left home or married or whatever. Some of them turned out very well, very successful, and a few of them didn’t make it too well. And, of course, by the end of the war we found out that there were not many left – a couple.

Now, on my mother’s side, they were Hungarians which was the old Austro-Hungarian Empire. They too came to Vienna. My grandfather was married for the first time and had two sons. His wife died and he remarried, and then came two daughters, one of whom was my mother. They all spoke Hungarian and Austrian and some German. They too were Orthodox and lived two doors away from my father’s parents. My mother then met and finally married my father. He was very lucky. He wasn’t taken into the Army during the First World War because he had flat feet. He was in the textile business. He was a porter of some kind because the textiles had to be transported and he did that. He then worked himself up to a partnership and ownership. He did extremely well and was an extremely successful businessman all his natural life. That’s the background of the families.

None of the grandparents made big riches but they all were honest and they survived quite well under the circumstances. This is the prehistory of this thing.

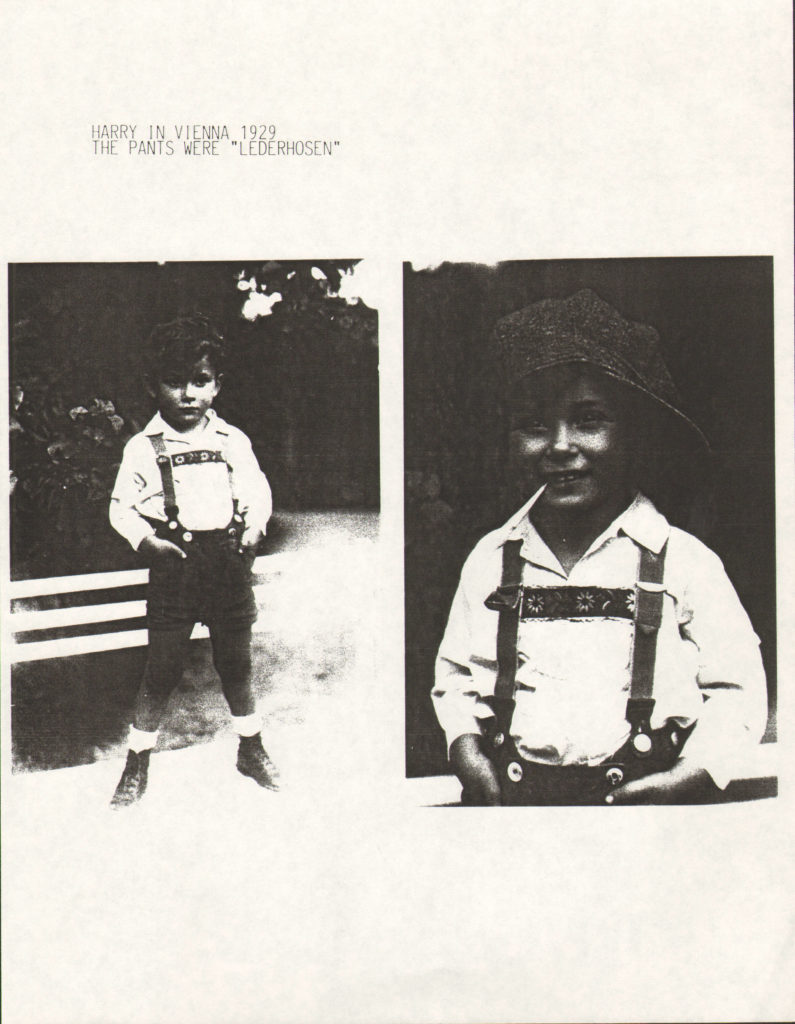

I grew up in an affluent area of the suburbs. My father at that time already owned a house. This was before the mortgage days when you have to have the money to buy, and he obviously did. He bought a beautiful house in the suburbs in the district where I grew up until the age of 10. At that time, my father sold the house, moved into the inner city close to where his business was and we moved into a tremendous apartment which at one time was a summer residence home of the Kaiser. The house had three stories, it was something. The first story was the Kaiser’s, the second story was for servants and the third story was for subservants. It was sensational and I remember that quite well. That was when I finally went into a middle school and you attend from age 10 to age 14. From six to ten we went to a primary school, after kindergarten. Then at ten you went into the first four years of high school. From 14 to 18 you went into the high school and at 18 you graduated and you were ready to go to medical school.

YOUNG: That’s if you wanted to be a doctor.

BURGER: Or law school or whatever. You could go to any professional school from there on in, and in four years you were done. This was like almost college, the last four years of med school. Of course, I didn’t finish it. When the Germans took over Austria, I was 13 and I was promptly thrown out of school, all Jews were.

YOUNG: Were you the only child in the family?

BURGER: I have a sister six years older who now lives in New Jersey, but she was not involved in the Holocaust. She got out before that.

YOUNG: When did she leave?

BURGER: She left Austria in 1938. I don’t know if you’re going to – this is going to be a mish-mash, but my father had a big wedding for my sister who married a Polish boy, an opera singer. My father was crazy about opera. So when the Germans came in, he bought him a falsified Greek passport that got him out of the country. So, he went to Italy where he studied voice and then decided to go to France. There he got a job with the opera of Monte Carlo, but they were Greeks now, so they were out of it, and they were able to leave France before anything happened and get to Cuba. That’s how they got away with it – he didn’t, but they got away with it. This was just a slight interjection.

I was out of school by the age of 13, never finished what we call high school here.

YOUNG: When did the Nazis take over Austria?

BURGER: On the 13th of March, 1938. Everything became German instantly. This was the amazing part of Austria that they were totally prepared for the takeover for years and years before. On the night of the 12th, all the officials, the police officers and everybody had the white and red armbands on their arms. On the morning of the 13th, when I woke up, they all had the swastika on their arms, ready to go. The flags in the windows were all changed from one to the other overnight.

YOUNG: Did you feel, before the Nazi takeover, any incidents of antisemitism?

BURGER: Oh yes. What happened at that time, you see, the Nazis tried to sway the elections to come. We were supposed to have elections in March. They decided that it was no good because it wasn’t sure. The Austrians were still pretty strong. Schuschnigg was the president at the time and had a pretty strong party, and Hitler didn’t want to take any chances, so he took over with the threat that we were going to have a blood bath and we said, “No, we don’t need this.” Austria had an Army of three or something, you know. There was no way. At that point they had street fights and it wasn’t safe to go out at night because they were out with the brown uniforms already and were beating up on people and there were especially Jewish slogans. So, it started, it wasn’t there yet, but it started. They took the liberty.

YOUNG: When you were in school, were you the only Jewish boy or were there others?

BURGER: I was already flunked out of certain situations by Nazi teachers before hand, and definitely flunked out because I was Jewish, and all the other Jewish kids had a problem. So it was very visible to me that there was antisemitism, a tremendous degradation.

YOUNG: Did it affect your father’s business?

BURGER: Unfortunately, my father’s business was affected in the wrong way. As soon as the Nazis walked in, with him being in textiles and the free flow of merchandise coming in through Czechoslovakia and France, my father did business like never before. All the Germans came in and bought quantities and he started making money hand over fist and said, “This is funny stuff, I’m never going to leave here.” False pretense. And all the so-called friends of his said, “Don’t worry about it, Burger, we don’t want you, we want the Orthodox, we want the Hasidic, we want the ones with the peyos’. You are safe, you are one of us.” And he believed it, he was a very optimistic man. What happened was that they let him make all the money he wanted and then about six months later, he got himself arrested, put in jail, stood for six weeks and then they presented him with the facts. Either he had to sign over the business and everything he owned, or they would put him into Dachau, which wasn’t yet a gas chamber camp. It was a concentration camp, but you knew that most people there didn’t come out. So my father realized that his life was more important, so he signed everything away. So, after all that work and all the money accumulated, they took it. But I don’t think they took it all. My father had a Swiss bank account with a number which nobody ever knew except him, and he died with it in Auschwitz. But he had about a million Swiss francs in there which the Nazis didn’t get, at least. But we didn’t get it either. That’s how it went. After he learned that severe lesson and he lost it all, he concentrated on emigration, on getting out.

YOUNG: But before that, knowing what was happening to German Jews from 1933 on…

BURGER: We really didn’t know what happened to German Jews. I had an uncle in Germany in 1933 and I remember, in 1934 he came to Vienna, he ran. And he came to our house in the middle of the night. I was a little kid. He said to my father, “I’ve got to stay here, I can’t go back to Germany. It’s terrible, it’s horrible.” My father said, “Oh, you always exaggerate.” He didn’t believe him. That uncle now lives in New York City. He’s an old man. He was a conductor at the Metropolitan Opera House and nobody wanted to believe how bad it was already in 1934 in Germany, what they were doing to the Jews. Everybody thought they were kidding around. Nobody believed it. So, when it happened to us and everybody said, “Don’t worry about it, we don’t want you. This is a great country now. You’re all going to be fine, maybe a little second class citizenship but that’s about it.” But the basics they weren’t going to do anything about until – when was it – I think it was the 10th of November when that kid – Dreyfus, or whatever his name was, murdered the German diplomat in Paris. I don’t know if you remember that one. Then they declared the 10th of November “Open Chase Jew Day” – “Whatever you want to do to them – kill, beat them up, rape them, destroy them, steal from them, whatever.”

YOUNG: Was your family personally affected by this?

BURGER: That particular day?

YOUNG: Yes.

BURGER: We all got away with it, and how? My father was in the area of his office when it started in the morning, and somehow was able to hide for the day. It only lasted one day. I was home with my mother, and my cousin, Fred, visited. Now, cousin Fred is a special case because he’s a blond, blue eyed Jewish kid who at the time of the takeover was in the Austrian Army. When the Germans took over and saw this blond kid, they put a swastika on his chest and told him that he was now in the German Army, never thinking that this kid could be Jewish. That day, he was at our house, shivering just like everybody else, but when they knocked at the door, he opened it and they gave him a fast “Heil Hitler, and thank you very much” and left.

YOUNG: How did they identify Jews on the street? Were they looking at the most Orthodox?

BURGER: They used to go to the caretaker of each home, each house and ask, “How many families have you here? How many Jewish families?” And they gave it up easily.

YOUNG: So the Austrians…

BURGER: Gave them all up.

YOUNG: Were you registered in some place as a Jew?

BURGER: I don’t believe it happened right away. It happened later on that they registered everybody.

YOUNG: And you didn’t have to wear armbands?

BURGER: No, not until quite a bit later when I was gone already. I never had to do this. Everybody in Austria wore a little swastika, a gold swastika, on their lapel. If you didn’t wear it, which you were not allowed as a Jew, and they saw you without one, you would get shot in the head. That was the extent of it at that point.

YOUNG: The Nazis identified themselves.

BURGER: Yes, and if you were an Aryan and you didn’t want to be a Nazi, you got a shot in the head too. It was as simple as that. Either you were for it or against it.

YOUNG: You said your father tried to emigrate after he was released from Dachau?

BURGER: What happened was my sister and brother-in-law were in Nice, in France, so the logical path at this point was reuniting the family. To get into Italy was simple because you needed no visa. All you needed was a passport. So he went to get a German passport. I recollect that it was a Gestapo facility where you got the passports, where they checked out your properties and whatever you had owed or whatever, and after a long time of insult and what-have-you, they issued a German passport with a red “J” on it. When we finally got that, it was a simple matter to get on a train and go into Italy. In Italy they really had a business. You could go into the north of San Remos somewhere and there were these guys who could get you over the border illegally because the French wouldn’t give them a visa.

YOUNG: What year are we talking about?

BURGER: April, 1939.

YOUNG: That was before the war started.

BURGER: That’s right.

YOUNG: So these visas to go to Italy were issued…

BURGER: There was no need for a visa to Italy because they were allied with Germany.

YOUNG: So, there was no border crossing?

BURGER: There was a border crossing but only for property. They would check your valise and your passport, but you didn’t need a visa.

YOUNG: So, with an identity pass or a passport…

BURGER: A German passport and you went.

YOUNG: …even with a “J” on it…

BURGER: It didn’t matter to the Italians, they didn’t even know what a Jew was.

YOUNG: Did a lot of Austrian Jews get out this way?

BURGER: A very small amount went that route. Most of them tried for further countries. But, you see, this was a first step.

So we got into Italy at San Remos and we got to the border. The first time they were promising us crossing the mountains and the Italian troops, the patrol, was going to look the other way, and it never happened. The real way was through a garden, a large garden which was on the border, half in Italy and half in France. It was owned by a doctor Wernoff, a Russian doctor who was a scientist. He was probing into the youth serum with monkeys. There were a whole bunch of monkeys in that garden. We got in there on one side, and on the other side there was supposed to be a taxi waiting to take us back. That you can forget. They took the money, they got us in, and it was up to us to get out, (LAUGHTER) which was a lamppost. Now we were sitting in France, not knowing the language, we didn’t know where we were, we didn’t know if we were going to be arrested or not. We didn’t know what it was now, to live in a peaceful country, a democracy. They couldn’t care less about anybody. We walked ourselves to the first town, got a bus and got to Nice, scared to death.

YOUNG: How many of you were there?

BURGER: There was my father, my mother and myself, and another fellow that my father had been in jail with, a lawyer from Vienna. He spoke two words of French, incredible at the time but was in fear. We got into Nice in the middle of the night and we had to go to a hotel, but we had no papers to show them – French papers – and we were scared. The man couldn’t care less. The passport was fine and he didn’t even ask for that. So, in the morning we met up with my brother-in-law who took us to the local police station. We had already made arrangements and they gave us a temporary permit. It was simple then because there was no war and as long as you could support yourself, France didn’t throw you out. They kept giving you a new permit every month until maybe after six months, you got a permanent white card.

YOUNG: So it was like a temporary permit?

BURGER: It was a temporary heaven. You see, no one believed in war in France because the French were very idiotic and cocky. They said, “They wouldn’t dare! You see what we did to them in the First World War!” And then when it became war, they said, “Don’t worry. In three weeks we’ll be in Berlin.” And we believed it.

YOUNG: But, backtracking just a little bit, before your father decided to leave, what was it like living in Nazi occupied Austria?

BURGER: It became extremely difficult. I did not go into the streets anymore.

YOUNG: You didn’t go to school, you were expelled from school?

BURGER: Once I was out of school, I was kind of a prisoner in the apartment. They made us sell all our property in the apartment and give up that good apartment. It was a Nazi auction. What it amounted to is that two officials came in after they placed an ad in the paper, and they auctioned off your property. It generally took about two hours. It brought about three American dollars – that’s how they did it, and they didn’t give you the money, only a receipt for it. So you got nothing. You got rid of your stuff, people came with their own trucks and took it away. Two hours later, it was empty and we moved in with some other relatives, some cousins, in a lesser facility, and from that time I stayed in until we emigrated.

YOUNG: What was the Jewish community like as far as trying to help other Jews?

BURGER: We had grapevines. The community tried – it was kind of subdued, of course, because the synagogues were closed down.

YOUNG: They closed all the synagogues?

BURGER: They were burned and what have you. They went further than that, they didn’t just bother the Jews, they went into the Catholic monasteries and threw the priests out the windows. They couldn’t care less about anything. It was total takeover and chaos. You wouldn’t believe it – and they were proud of it!

YOUNG: Were they arresting the rabbis at that time or were they letting the religious leaders…?

BURGER: Everybody got in the background. Whoever didn’t get killed on the 10th of November, they went in. I mean, there was no more public appearances or getting together or anything. It was total destruction of the Jewish community at that point.

YOUNG: Were there secret meetings of Jewish people?

BURGER: I couldn’t tell you that, but what I know is that they were encouraged to leave the country. If you wanted to make it alive, get out! They were encouraged to do this – “Get yourself a visa and we won’t stop you. Just go!”

YOUNG: So, they took away people’s property and sold it for nothing, and told them to leave as best they could.

BURGER: Absolutely. And, “You’d better, you’d better. There is no future here for you.” And they didn’t tell you exactly where you were going to wind up, but they sure made it pretty clear. “Remember the 10th of November.”

YOUNG: Was there panic among your friends or relatives about people who didn’t have access to money or…?

BURGER: Well, again, my father helped quite a few people by giving them money to get out. None of them ever had any plans to come back to us and the money wasn’t intended to. As long as my father had it, he gave money. The funny thing about this is that most Jews who immigrated at the time found a way to get some of their possessions out through a non-Jew who wanted to cooperate. In our case, my Uncle Bernhard was married to a Catholic woman and she did the trips. She went into Italy with the gold cigarette cases and this and that, and the cameras, and brought them out. But everybody had a source. Nobody got that broke because I remember that first year in France, we lived with our income. Nobody worked. I had a job for 10 francs a week but that’s moving money. And everybody lived well and could afford things.

YOUNG: Did people feel that leaving Austria at that time was temporary, that as soon as Hitler was overthrown, they would return?

BURGER: At that point, nobody thought war. We left the country permanently. We had to regroup and our big goal was America. We had already applied for a visa. We had an affidavit and we applied in Austria, but the quota was so heavy, and my father having been born in Poland was in the Polish quota which was an impossibility.

YOUNG: Very few Polish – the quota was very small for Polish people.

BURGER: Yes, and it would have been like a 20 year waiting period, so it was useless at the time. So, he looked for other sources and the next source eventually became Cuba – to get closer, to get away from them. It never happened but that’s what he was after.

YOUNG: But at that time your sister was in Nice with you and your brother-in-law. They got to Cuba.

BURGER: They left for Cuba. They still got the boat. They had everything going for them. My father put up the landing money which was $1000.00 per person. He must have had the money somewhere – right?

YOUNG: Yes.

BURGER: And they went. Now, they were supposed to make all the arrangements for us and my father sent the landing money, but he never got the visa. Later on, I can come back on this, because my father got deported because of Cuba – it connects.

YOUNG: What exactly happened?

BURGER: What happened was that he went out and bought a falsified Cuban visa for the family and came home with it. It looked horrible and I even said he wouldn’t get out of the country with it. So he went back to complain to the people who had sold it to him for heavy money, and the police were there already to arrest these crooks. They asked my old man what he wanted and he said, “I want my money back, I got cheated.” They asked if he wanted to testify to that and said, “Come with us.” He went with these people to the police station and they put him in jail for six months with seven others, and never let him out until he went to trial. He got acquitted and then instead of letting him go out, they put him in a concentration camp on the Spanish border which was nothing more than a holding camp for the Germans.

YOUNG: Which camp was this?

BURGER: Gurs. And that was the end of it. He went to Auschwitz from there.

YOUNG: Where were your mother and you?

BURGER: At that time, in Nice.

YOUNG: So you were able to stay on in Nice?

BURGER: Nice was the unoccupied French.

YOUNG: Now are we talking about after the war started?

BURGER: We got lost there. This is what happened. We couldn’t get to America even though a telegram came that we had the visa. The quota number came two days too late from Washington. The last boat had gone. Without a boat, no way. So we were stuck. But again, the way it looked in the non-occupied French zone, you could possibly survive with a little bit of luck, but you had to project ahead what was going to happen. Were the Germans going to be beaten? Or were they going to win that war? It looked for a long time like they were going to win the war. Don’t forget, we had no communications like we have today. Nobody really knew what was going on in the front lines except what they told us. We were in a German area and we saw the German movies, and they were terrific. They won everything, so it was very discouraging.

YOUNG: But you and your mother were free to go out and live on the savings from your father?

BURGER: What happened there after France was occupied – France was heavily occupied – and this became the free zone. The authorities were pro-German, of course. They were collaborating, and whenever you went for your permit renewal to the police station, they wanted proof of financial security, which meant you had to bring a bundle of money. There was one bundle of money that circulated among all the immigrants. The same money went down there all the time and they’d say, “O.K., you have money.” Once in a while they tried to get some people into Germany as slave labor – or in the case of the Jews, of course, to concentration camps. It wasn’t all the time, but once in a while there was this kind of situation where if you went, you didn’t come back. Now we had grapevines and people we knew in the police station told us, “Don’t come this time,” when they sent us the notification to come for our permit, “because this is the drive.” And this is how we got away with it because we just didn’t show up till it was clear again. But the French were bastardly, like the Austrians. They were totally for the Germans. They hoped the Germans would win the war. It was the alternative (they thought) to being governed by Jews and Communists. That was their prime objective. They were terribly antisemitic. But somehow you could cruise it. It wasn’t as though any minute you were going to get it. It was a matter of luck.

YOUNG: How many Jews would you say were in a position similar to yours?

BURGER: At that time, in that area, I would say we had about 2,000 maybe, in a town of 250,000. And it all worked to perfection, maybe even better, when finally in 1942 (I think) the Italians occupied the non-occupied zone because the French scuttled the navy too long and the Germans said, “O.K., that’s enough nonsense.” There were 35 or 40 boats down the drain that could have been in the German navy, so to the Italians who had been allies, they said, “Go ahead, take them.” So they took the southeast of France and we were there. Now we were in the Italian occupation and they were pussycats. They were dolls and lovers. They didn’t want to make war. If you told them you were Jewish, they said, “What’s a Jew?”

YOUNG: Had they never seen Jews or met Jews?

BURGER: They didn’t know about Jews. They didn’t know what it was. They thought they were devils with horns and a tail. They were ignorant about the entire thing. So, how bad could it be? They allowed the synagogues to exist in full force and that was a communication point between all the Jewish refugees and the Italian occupations forces.