BERNSTEIN: This is Rick Bernstein interviewing Jan Verdonkschot at his home on 5/9/85. Could you please tell me your name, your age, and where you were born?

VERDONKSCHOT: My name is Jan Verdonkschot. I was born in Heemstede near Haarlem in the Netherlands. I’m 56 years old.

BERNSTEIN: Could you tell me a little bit about your family and your childhood and where you grew up?

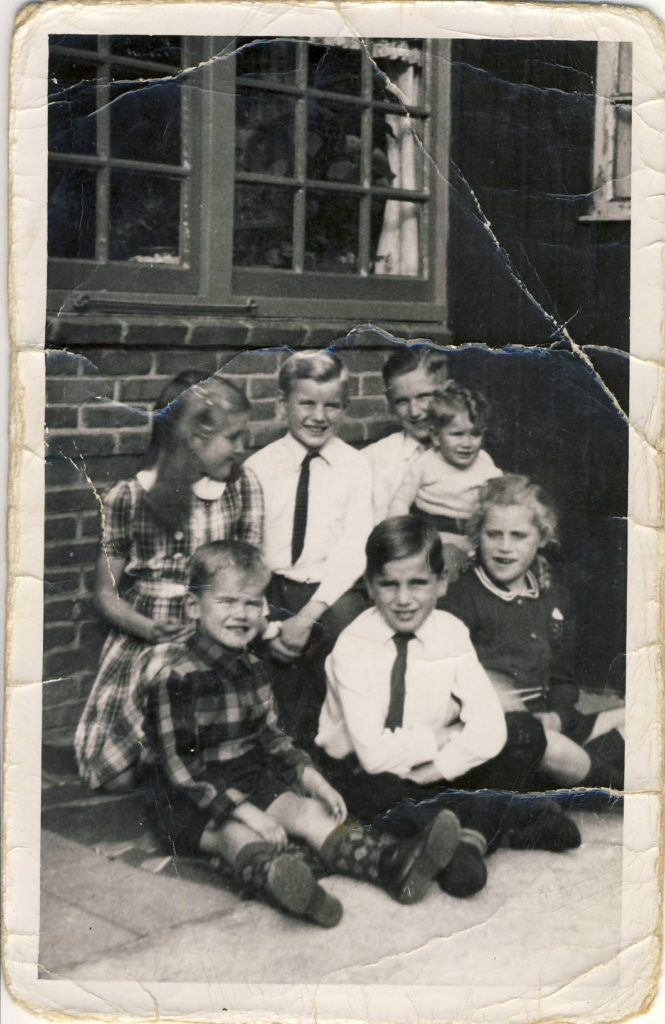

VERDONKSCHOT: I grew up in Heemstede and my dad was a tulip bulb grower and we lived outside of Amsterdam. I have a vivid memory of when the war started or when the Germans invaded the Netherlands because from my home you could see the smoke coming out of the gasoline tanks that had blown up when they invaded the Netherlands. And I very much remember them marching into our town and that was when I was a small child, of course—in the ‘40’s—1940.

BERNSTEIN: And how old were you, once again, in 1940?

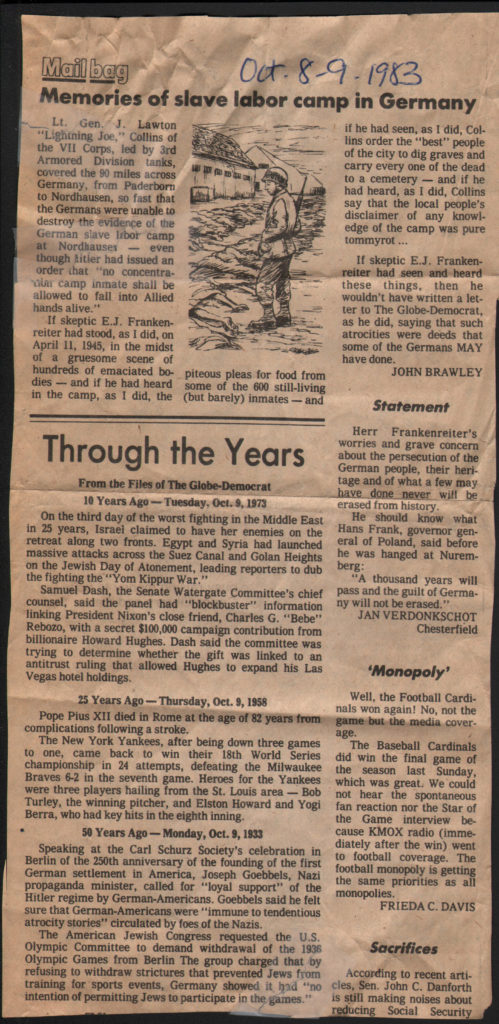

VERDONKSCHOT: In 1940, I was 11 years old. In 1942, the latter part of 1943, I was witness of several murders in person, and I was never too quiet a person. My dad was well known in our town and they had attacked two collaborators of German regime. First, he hacked them out of a State car with a rake and I was there, and the police came to my home because I’d already been witness to the killing of a guy on his bicycle and they thought I was involved in this because it seemed that every time something happened, it never did happen, you know. It very seldom happened because murders, or things of that nature, were hardly ever heard of in the quiet place where I was born. So, the police had then suggested that it might be better if maybe—it would be better if I depart and then my parents brought me to North Brabant, which then you have to take a train to Amsterdam from Haarlem which is near Heemstede, Haarlem, Amsterdam, and I ended up in a very small village in the country by the name of Overlone. Overlone was—also in the town there was also a camp for laborers…a labor camp, they called it, but they were young kids who marched with shovels rather than with guns. Later on in the war, though, they used them as protection from the Germans. They’d chase them ahead of the troops so they could get killed easily. Also in this town, there was more people living underground and there was more resistance movement in this one town than virtually any place else in the Netherlands, and how come I got shipped over there, only God knows. But—so I knew quite a few, or many illegal people, who virtually lived underground and I arrived there in 1943 in this village called Overlone.

BERNSTEIN: Were your parents with you?

VERDONKSCHOT: No, no. No, my parents, when they brought me there and then they left me there.

BERNSTEIN: So who did you stay with?

VERDONKSCHOT: I stayed at the home of a barber. His name was Van Klopek, and I stayed in that home. And his brother was the head of the resistance movement in that entire area. Even later on, I remember him being a very asthmatic person. He was later on made the director of the War Museum. There is only one War Museum in Holland, and this happens to be also in Overlone and I have some newspaper clippings from this over here. Though traveling in the train, I don’t recall ever going home again.

BERNSTEIN: Did you go to school in Overlone?

VERDONKSCHOT: No—I was out of school. You know, even during the war, schools—wherever I went to school—schools were taken over by the Wehrmacht, you know, and I remember having my last class sitting in the grass over a ground where there was a Catholic Seminary, and that Seminary had been taken over, too, by the Wehrmacht, see, by the German soldiers. School was just about null and void.

BERNSTEIN: So, what did you spend your time doing during the day?

VERDONKSCHOT: We were working, gathering in the yard at these people’s home, helping this guy in his place, in his barbershop, running errands, doing things that were sometimes totally illegal because we had other young kids there—young men—and we even had four in the underground scout troop. Because that was another thing against the regime, you know, the German—

BERNSTEIN: What kind of illegal things were you doing with other young men?

VERDONKSCHOT: Well, this will come up later in the story when the Battle of Overlone comes, you know, where they sent me out to spy on the Germans. However, traveling through the Netherlands by train, you know, I saw many train loads of Jewish people being shipped to a camp, and we stopped—the train stopped in a camp and I was in Werft, and we saw the people in the cattle wagons and so we were well—everybody was well aware of the fact of how the Jewish were treated.

BERNSTEIN: What did you think at that time? Where did you think the Jews were going? What did you think was going to happen to them? Did you have any idea at that time?

VERDONKSCHOT: You know, the Dutch have a—in most instances—they have a closer relationship to Jewish people than I think most other people have. They have another—a different type of affection for Jewish people, especially because—close by—in Amsterdam was a very Jewish city. Later, after the war, when I started to go to sea, you know, I worked with many Jewish people—boys, you know, and young men and stuff, and you know, even in the language, in the slang of Amsterdam—and by the way, Amsterdam is called Mokum*, which is a…

BERNSTEIN: A Yiddish word?

VERDONKSCHOT: Yiddish, Yiddish. In the language of Amsterdam, there are many Yiddish expressions, you know. Like schlemiel**, and—well, so many that I, you know—anybody when they start talking, I can understand virtually a lot of it, you know. So I was not necessarily raised with Jewish people, but we always had very high regard for them. We had some very close—and I can show you a painting of a Jewish lady who painted me here and were very close friends of our family. So we had—we had a high regard for Jewish people. So when we saw the Jews being treated—they were being stigmatized with a mark, you know, of the Star of David, you know, that really pulled them down, you know made them so much less than—like a cattle being branded, you know. And I know that—

BERNSTEIN: Did you have—what were people saying about what was happening to the Jews?

*Mokum might possibly be Mr. Verdonkschot’s pronunciation of “Makour,” which in Hebrew means “place” or “my place.”

**Schlemiel is a “fool” in Yiddish.

VERDONKSCHOT: Well, I guess they didn’t do as much as they did in Denmark, but a lot of them did—went underground, you know, like Anne Frank in Amsterdam—where they were up in attics and hidden, you know. I know they were—later, after I came home, after the war, I found out that people had also been stashed away in cellars because basements—they don’t have, you know, because of the water problem—or in attics and in farms, you know, in false haystacks and stuff like where they have been kept for years, you know, and fed and protected, you know. But, many were dragged away, too.

BERNSTEIN: Uh-huh. Did you—once again, I’m just curious—at that time, when you saw the Jews being loaded in boxcars and being transferred wherever, where did you think they were going? Did you have an idea, did you think—

VERDONKSCHOT: I know, I know, but I’m sure they were not gonna go to a summer camp because you could see that, you know. Because—you know what always surprised me? That they were so silent and they had been—I don’t know why—you didn’t hear any screaming, yelling, or hollering, you know. I mean, you saw a lot of shoving and pushing and dragging, but I never heard too much noise. Now I do remember one case where a fellow who was a (Dutch word), more or less like a fruit handler, behind his wagon and hookup, beat up because just like a lot of punk…Nazis, you know, like some of the Dutch collaborated. They had the—what they called the N.S.B.-ers. It was a National Socialist Bund or a National Socialist Organization.

BERNSTEIN: The Dutch Nazis?

VERDONKSCHOT: You know, the Dutch Nazis, you know, the traitors, who were just as bad, or even worse, because they were the trash of the earth, you know, who had followed. But I guess because of the style at my home, where everything was very neat, but my dad had lots, many brothers, and I went to a Catholic school. And he had one brother there who had—was in the underground and he got shot in our town because of clandestine radio operations and stuff like that. And I guess that was the first inkling, at my young age, those people are enemies, you know. And I guess they must have talked about it quite a bit in my home, so it was kind of instilled in you, you know, that those people—you know, if you talked to a young kid, telling them day after day, you know, that blacks are no good, well after a while, they are no good, you know. And I guess it was the same thing with the Nazis. When they marched into our town, you know, there was nobody on the street waving them in. So even for curiosity reasons, they said, ‘I don’t want you to go out there and look because these people are coming over here and gonna take our stuff away from us,’ you know. And they took it away and sent the Queen away and everything else, so you kind of were—and also, with that school thing that happened. So we knew who and what was bad and indifferent.

BERNSTEIN: Can we go back to the—I’m not quite sure I understood—the two incidents that occurred in your home town that your parents thought you should be—

VERDONKSCHOT: Ok. One was at night in my home town. One was on the border, but being that everybody knows my dad and the police and everybody, you know, this was a small, very nice town. It’s something like, I guess a portion of Ladue, attached, you know, something like that. But these were—there were two guys and there were two collaborators and it was not a drunken street fight or a—

BERNSTEIN: Two Dutchmen were collaborating with—

VERDONKSCHOT: The Germans.

BERNSTEIN: With the Germans.

VERDONKSCHOT: And this happened when the streetcar came by and they had fled into the streetcar and while they were standing to get into the streetcar—and these were rather big streetcars, not like the smaller ones they had staying in this city, for example—they were more for long distance running. They’d look like a train, what that means, that there was high doors and high steps to get in. And they were both racing in there but the thing was full, and some guys who had come from, to work the fields, and we had what we call a strofel, which was the device which they use to weed with, which could be very sharp because of the sand ground there, it sharpens itself. And one guy slammed it into the back of the neck of this one collaborator and the other guy had a rake and he slammed it into the back of the head of the other one, and they pulled them out of the streetcar, see. And it really started then. And the other occasion was in front of a barbershop. They had killed the collaborator and he must have had some smart alec remark or Lord knows what happened. I just happened to be there, too. And they pulled him off of his bicycle and so many people got involved. The guy was under the bicycle and they just stomped him to death.

BERNSTEIN: So, life was not easy for a German collaborator.

VERDONKSCHOT: Not necessarily, because after the war I was in this place the first day, but when they were liberated the first day in my home town, of some people I knew, life was not easy for them then because they did just almost anything to them, you know.

BERNSTEIN: I see. So your parents thought you might be in danger because you witnessed these—

VERDONKSCHOT: That was because the police say, ‘It seems he’s there when two of these terrible things happened.’ It was too quiet of a place, you know.

BERNSTEIN: Ok. Did your formal education stop at that point?

VERDONKSCHOT: My formal education stopped. And I never went back to school until after the war.

BERNSTEIN: I see.

VERDONKSCHOT: So, I went to Overlone in 1943. I guess I was about 14, and then—let’s see, I wrote this down here—The Battle of Overlone, they called it a “second Cannes.” The village was—the men had all fled the village and I don’t exactly recall how many miles, but it was walking distance, the troops, the part of Holland was liberated of the south, anything on the…over the—what the heck was the name of the river now—that was all still occupied because the Battle of Overlone was on September 17 until the 24 in 1944 and let’s see—the dates I have to be careful with here because I don’t recall exactly when the Battle of Overlone was, which was called the “second Cannes” because the Germans had occupied the town three times and the Allies, which were Canadians and English and predominantly English and some Polish took the village back. So by the time we got back to it, you know, there was not one place standing on top of the other. Then what happened is all communications to the outside, to a town called Venraij were disconnected, and we had this labor camp there. It was a part of what’s called the “Arbeitsdienster,” the Labor Service, the camp.

BERNSTEIN: There was a labor camp in Overlone?

VERDONKSCHOT: Right. And that had emptied because they had sent all these kids with digging trenches or foxholes or something for the Wehrmacht, you know. And in the afternoon, (inaudible) and ear or a smell of a happening, and they had in the road remember, here was the Mayor’s home, and the road went around into a curve and the curve was kind of high, kind of hilly with sand dunes and bushes and then going here was that big camp and then the road when to Venraije, and here was Overlone, and it was a courier, a motorcycle courier, with a German officer. They were gonna go to Venraij to report something about—I think there were over 300 people living underground in Oberveen—to get troops or whatever they were going to do. So they hear of that, so they position themselves on the hill here in the bushes and then they shot the guy. They were gonna shoot the motorcycle rider so they can stop him, but they didn’t shoot him. They shot the guy who was sitting on the seat in the back, and they shot him off the motorcycle and the guy got away. And then the troops came into the town and all men were advised—we all left and we left our wives there ‘cause, you know, still they were stupid because they never learned the lesson they learn about a town by the name of Poeta where everybody was driven into a church and the church was struck afire and the same thing would happen in France, and we had something like that happen in Holland. I don’t know the name, by the name of Poeta. And so any able male was advised to leave, and some people had never seen—I’d never seen them in my life, and then finally I saw where they lived under—I mean, they virtually did call it underground—they virtually lived under the ground like rats, I guess. And they had to be kept supplied with food and drink, so there was, you know, there’s been a lot of hard times over there. And we left and walked through the heather fields to another town and I don’t know what the name of the town was, but we ended up on a farm and all the men spread around and it was hundreds of them. And then I was asked to go with another young guy because they figured that kids they do much to, to go back to town and find out if the German troops had arrived. We walked—or snuck into town, not walked, because we didn’t want to be noticed. And while I was laying behind a high hedge—it was a thorny hedge, and the flowers even smelled. I remember the smell of the flowers. A truck stopped with troops and they looked over the hedge and saw me laying there. The other kid run away and they got me and I was told to stay there with a guard. And this was a fellow, a German with a bicycle who had a gun strapped on his bicycle and he was supposed to stand guard over me and to hold me there because they were gonna interrogate me. And then an officer came by, and they do a lot of yelling and screaming, you know, these people, these Krauts. And I don’t want to forget, here was a small delicatessen store, you can call it. They sold tobacco and cigarettes and beer and you had a bowling alley, but not like here in America—they had sand where they bowl with the balls—on sand. In the back there was a part tavern then they had this store and it was owned by two sisters. And here was a big, point, off to the side by itself, and it was all gravel, and I was standing in the middle there with this guy and the bicycle and this officer came by. And he had then given him orders to shoot me, see, because I didn’t know what they were talkin’ about—with all the yellin’ and screamin’. We all spoke German but it was always better to pretend you didn’t know a damn thing about it. So I remember these two girls were jumpin’ up and down, screaming bloody murder because this guy, he was supposed to get rid of me there because I had no answers to his questions, you know. And the officer had parted, so, with all this yellin’ and screamin’ from these two women behind the window there and was jumpin’ up and down, this guy—he was an older German—I guess I gotta thank my life on that occasion for this guy because he patted me on the head and he told me to start running. I don’t remember ever peein’ in my pants, but I know I did at that time because I was soakin’ wet for many hours. I got, even I was embarrassed about it, but not realizing that I could have just, you know, have been killed.

BERNSTEIN: An older German—

VERDONKSCHOT: An older German had then let me go, you know.

BERNSTEIN: I see.

VERDONKSCHOT: So I went back to where all the men were, and the wives, of course, wanted to know where the men, but this was then in the period of days and eventually all the men came back. But then this town had been mined and because I went back for some of my tools or some of my belongings and I remember they had plundered a lot of the places already—the Germans did, because I had a little saving bank, and I had kept that and tried to save some money in there, and it was made out of steel and that little handle looked like a little suitcase, and it was from a bank. And I went back in there and that’s when I almost got killed a second time by steppin’ on a land mine, and when I left there, then we were advised to leave because the village has already been taken over once by the Allies and once back by the Germans. So everyone was told to leave the village and then we packed the old people up and I had no personal belongings.

BERNSTEIN: So this time the entire population was evacuated?

VERDONKSCHOT: Yeah. A film was taken of that from the air because it must have been a sight to see, because I had an old woman on a wheel barrel which I pushed, and again, I do not recall the name of the place. You know, I haven’t really talked about this stuff. When you start talkin’ like this, you can’t—stuff starts coming back and–. We went to another town and there we were strafed, you know, by airplanes or things were goin’ on all over. There was constant fireworks. And then we stayed for the longest time in a forum in a cowshed and the woman I had pushed in the wheel barrel, she had got hit by a small piece of shrapnel, and we didn’t even know it and she was dead. And many other people—kids had died and stuff like that. And then I ended up in back and forth Germany, and then finally, with the Allies and most of those were English and then later on they became Canadians, and—

BERNSTEIN: So you could note the troop movements back and forth?

VERDONKSCHOT: Oh yeah. Yeah.

BERNSTEIN: And this was in what, 1944?

VERDONKSCHOT: This was all around 1944—and it was in the fall because—let’s see. I went to—in the winter, I went to Eindhoven where the Phillips Factories are and I—the people I was with most of the time, they had enough worries on their own, so I kinda just left, but then the Red Cross had given me something to hang on my neck and stuff like that, and they kept track of me, you know. So that was in ’44, and I didn’t know if my parents, if they were dead or alive or what because—

BERNSTEIN: You had not communicated with your family.

VERDONKSCHOT: No way to communicate, no. The first time I communicated with them was when I got this Red Cross thing here, which was sent via Switzerland by the Comite National du Craix Rouge*** through Geneva in Switzerland. The first time, that’s when I wrote them on March the 5th, 1945. So from…I say the fall of ’44 till after, till they found out in March that I was alive, you see.

BERNSTEIN: Now, as you were hiding with all these people, were Jews also hiding, or people that the Germans—

VERDOKSCHOT: No, these were all—no, there was no Jewish people there. I know that to be a fact. Most of these were—we called them the underground. Most of those were guys who were looked for because they were involved in killings or had blown up bridges or sabotaged. A lot of saboteurs were there.

BERNSTEIN: While you were in Overlone?

VERDONKSCHOT: That’s right. These were what we called the “Unterdaggers.” They—you know, there was no way, no other way. They couldn’t show their faces on the street because they were wanted criminals as far as the Wehrmacht was concerned, you know.

BERNSTEIN: I see.

VERDONKSCHOT: But now I don’t recall in this town any—any Jewish people.

***The Swiss Red Cross.

BERNSTEIN: The Jews that were in hiding in Holland—

VERDONKSCHOT: They, once they were in hiding, I don’t think they went as far as that, especially in the very small towns.

BERNSTEIN: Mainly in Amsterdam?

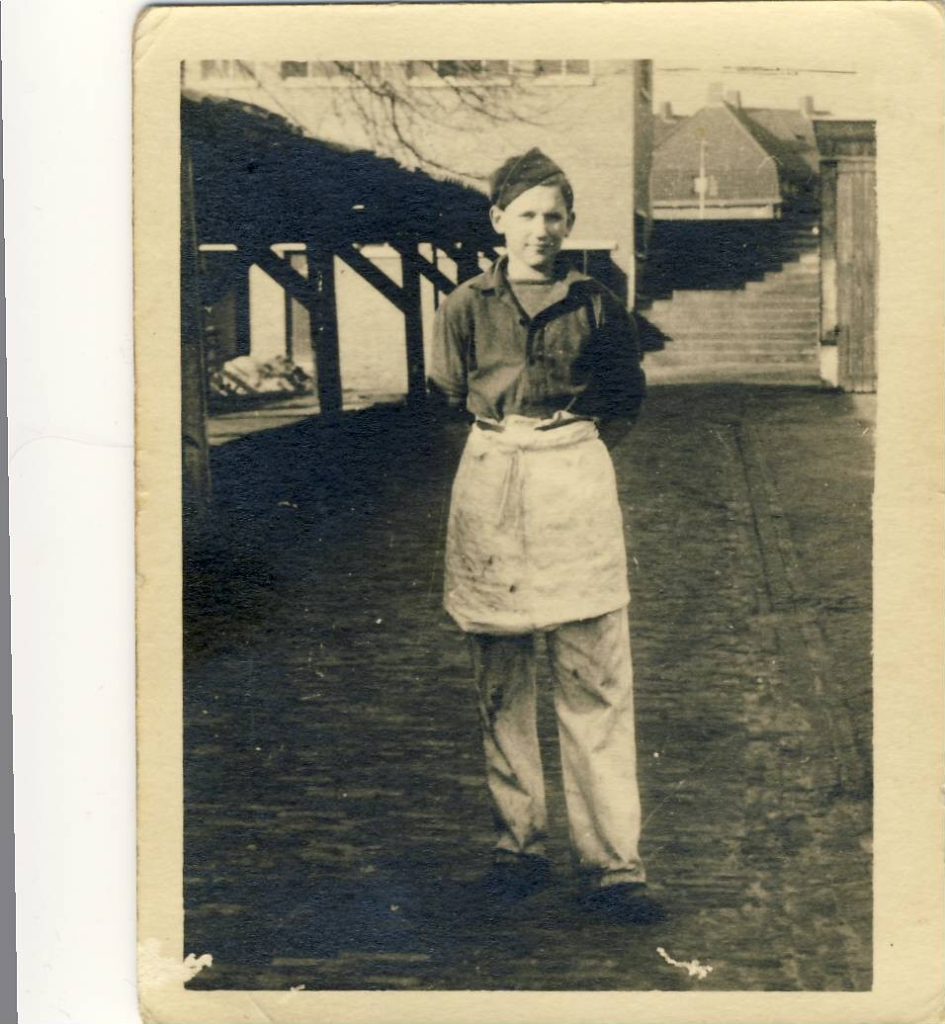

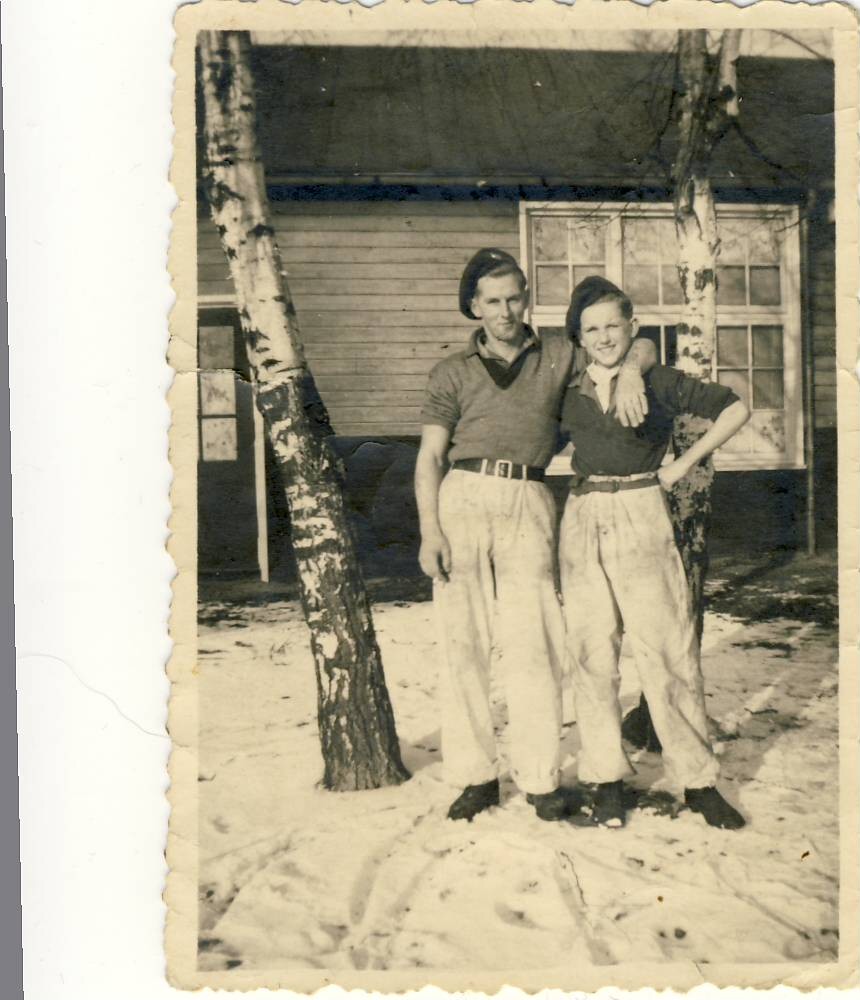

VERDONKSCHOT: I think they mainly were in Amsterdam, but I know they were in Heemstede where I was from because they were located there. Where we were, this portion of the part of the country in those days was predominantly Catholic, and like North Brabant is the name of that province, and Limburg is the next province. And those two provinces were predominantly Catholic provinces. Okay, then I ended up in the hospital, and I got terribly ill and depressed and I ended up in the hospital, bed to bed next to each other with a lot of war wounded and I didn’t have much place to go. They had tried to take care of me. Some Canadians came to visit the hospital and then they virtually adopted me. So now I became a waif of the Canadian army and I got measured for a Canadian Army uniform and now a Sergeant Major had taken the responsibility that for a year and one-half, because no one knew how long the war was gonna last, he was gonna be responsible for me, or he had the right to transfer this responsibility to someone else, except if I found my parents, then they had the right to claim me, you know. So I stayed with the Canadians for a year and a half. This was early yet after the war I remained with them because there was not much else to do, you see. So—and here is a—you see a picture of me here which was May 7, 1945 and May 5th Holland was liberated, and that’s what I looked like.

BERNSTEIN: So, after the liberation, you stayed with the Canadian—

VERDONKSCHOT: What happened, the first Canadian liberator came into my town, started a motorcycle and had let my mom know that I was alive and well and I was in Arnhem. I was one of the first Dutch persons to enter Arnhem, and you know, the city was terribly devastated because of this market garden attack in September of ’17, they fought the Battle of Arnhem in ’44. I stayed there with the Royal Canadian Army, while I was in Eindhover and the war was still very strong goin’ on. I was in Eindhover and then I was here. I was in Eindhover and the I worked in the kitchen. This was in January of 1945. Now I was about as big as that soldier there, as you can see. You see, I was not a physically scroungy kid. Too look at this picture now, you know, I look like my grandson (both laughing) or he looks like me. So I have other pictures, but these are just something I brought in. And I stayed with the Canadians to war end. And I got home. I was with the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps, the 65th Tank Transport Company. And I tried to become a—I wanted to go to Canada. My dad found out that I wanted to go to Canada, so he had the military police on me in Antwerp because I had tried to stow away on a Canadian ship called the Hampstead Park, and by that time, my dad was fed up with me prancin’ around in a Canadian uniform.

BERNSTEIN: You wanted to go to Canada, and your father wanted you—

VERDONKSCHOT: He wanted me to come home and go to school, you know.

BERNSTEIN: I see, I see.

VERDONKSCHOT: So I remained with them till…September of 1946. So I was a good year and a half with them, and that’s when my dad said, ‘Hey, come home and go to school.’ And then I tried to go to school—