Were you taught in school to tell on each other?

BUDER: No, not that I remember. No we were not.

PRINCE: I’d like to go through whatever you would like to describe as a typical day in school and then I would like to be sure that we discuss the Hitler Youth.

BUDER: Yes. Well, I was a little too young. I was in a group and that was absolutely mandatory but you didn’t have to swear anything. I was, thank goodness, young enough so I was in a group called “Bund, Jungmadchen Verband,” I think it was called. It was like Brownies. There was a Bund Deutcher Madchen, the B.D.M. where you were actually sworn in. It was just like the Hitler Youth, for the boys and before the Bund Deutcher Madchen you were automatically – everybody was in school – we were in the Jungmadchen Verband, but you would just get together like scouts, like Boy Scouts. Sure, we had to wear a uniform and we had to sing Nazi songs but we didn’t have to make any declarations. One thing, however, that I did have to do – I was in the choir and we had to sing at weddings and one day it just happened to be the 16th of December, ’44. We were practicing in a room in a hotel for a wedding and it was a real Nazi wedding. I had never seen or attended a Nazi wedding. In other words, the man was in uniform and the woman, I guess, was in bridal gown – we never got to it. While we were practicing there was the first terrible bombing attack on Siegen at one o’clock on December 16th.

PRINCE: You haven’t forgotten that?

BUDER: I haven’t forgotten that and if nobody remembered that we were singing, that we were practicing in the back room. So when the siren sounded, everybody left and forgot about us, and because we were singing, we didn’t hear the siren until the bombs started falling, and the hotel was immediately hit and I, myself, remember just slithering down some steps and I ended up down in the lower level where the bathrooms were and the water burst and it was so terribly loud that I really thought my head was going to explode. Because the water was rising down there among all the toilets, I somehow got up again but the front entrance was burning, so I ran up to, I guess, the second floor and I remember standing at a big open window with everything burning down below. And on the street were a lot of people but I realized that they were all prisoners of war. There was a factory across from the hotel and all the prisoners of war were not allowed in the shelters. There were shelters all over town – tall buildings – they were not underground. And there was a great big Russian man standing down below and he just waved to me. I could see he was Russian by the kind of uniform he was wearing. They were all identified even though he was a prisoner of war, working in a factory. And he waved and waved and waved, and I was in uniform. I wore a white shirt and black skirt and a black scarf with this leather thing. I didn’t have any emblems on me. This dear man waved to me and I just jumped and he caught my fall and then he took me and he – they were burning trees and burning horses and everything – and he would just take me and just throw me across or jump across with me and we couldn’t even talk to each other because he was Russian, and he ran with me to the shelter and he just shoved me in there, and he was not allowed to go in.

PRINCE: He couldn’t go in himself.

BUDER: Yes. So there were nice moments like that.

PRINCE: You must have been so frightened.

BUDER: Well, I don’t know. Sure, you’re – but you’re beyond being frightened when something like that happens.

PRINCE: Like in shock?

BUDER: Yeah. Well, the whole town then was burning and you would see people on the tops of buildings, screaming for help and the whole building was burning and you couldn’t help. You saw some terrible things then.

PRINCE: Like a nightmare.

BUDER: Totally, yeah. My mother happened to be in town shopping that day and she knew that the shelter was right close to the hotel, and she figured that we were all in the shelter, and she made her way to the shelter and found me. Actually by the time this man just kind of threw me toward the shelter, the heavy doors were all locked, but there was always sort of a little vestibule almost in the front of the actual doors to, they all had that, I think, to keep the wind pressure from these bombs out of the actual shelter. So, when the attack started, they would close the heavy doors, but then there was always still some room where you could stand at least in front of the shelter. There was still a roof but it was open and that’s where I was and where my mother found me. She had been in a shelter in town but she had bought some bottled water, some lemonade or something like that, that day, and that actually might have saved our lives because we had to get through so many terribly smokey areas and we used some handkerchiefs or something – I don’t remember really what it was – I guess it was handkerchiefs. So, we just slammed the bottles against a wall and soaked the handkerchiefs with the lemonade and held it in front of our faces to get through some areas that were totally very hot and smokey.

PRINCE: What did people act like in the shelters?

BUDER: Well, in the shelters you just sit there stunned. You don’t cry or complain. It’s much too big. You don’t carry on. In the shelters I remember, everybody was just stunned.

PRINCE: It must have been very difficult because they had been told and promised and all of a sudden…

BUDER: Just total disaster, yes, right.

PRINCE: Was it possible that it came in small parts, though, that there must have begun to be shortages, there must have begun to be…

BUDER: Well, there was constantly this promise of, “Wait, just hang on and wait. There is a wonder bomb.” I guess the V-2 or whatever that was called.

PRINCE: V-2, I think you’re right. I was going to say V-8 but that’s (LAUGHTER) tomato juice.

BUDER: (LAUGHTER) I think it was the V-2, and up until the last minute there was this talk about everything is going to be allright. “We’re just bluffing and we’re just letting them think that we’re getting worn out, and Hitler is in control and he’s going to set off this V-2 bomb,” which of course was totally stupid.

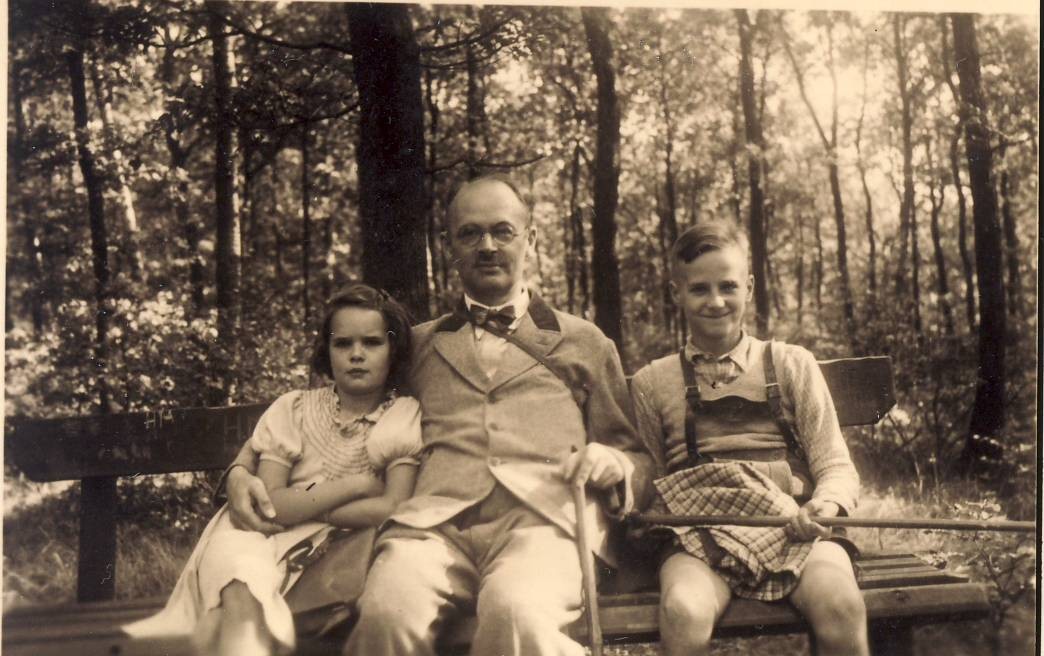

Now I have asked my parents, naturally, this big question. We all discussed it. They did not know what went on in these camps. They knew that people disappeared, that people left. Most people that we knew – well in Siegen there weren’t terribly many, well, there were Jewish people, yeah, but not terribly many ‘cause it was such a small town, and they knew that there were places where they were, I guess, collected or had to go through. They did not know, and I completely believe my parents, what went on in places like, like Dachau and Auschwitz.

PRINCE: But in Dachau, originally Jews were not the first taken into Dachau and people like your father or Catholics…

BUDER: Or homosexuals…

PRINCE: Right, just people who spoke out against them, priests – they were the first people to go to Dachau and after a while they took the Jews. But the beginnings were – and that’s why you were so fortunate that your father did it in such a way that he wasn’t taken.

BUDER: Well, and that was another point – the Nazis were so extremely powerful so fast because they executed people from within their own ranks very quickly and openly, which, of course, sent utter terror through – I can’t think of his name right now – the head of the SA, the first –

PRINCE: Rohm.

BUDER: No, not Rommel, of course…

PRINCE: No not Rommel, R-O-H-M, because he was head of the SA.

BUDER: He was head of the SA and was he not homosexual or…

PRINCE: They all had a perversion of some kind, I believe. I think he was.

BUDER: Yes. So, he was with people from their own ranks, and then the threats, of course immediately went out. If more people had rebelled against the system earlier – I mean very, very early – maybe it could have been changed. And I cannot help but think of where were the terrorists during the early ’30’s. Now we have terrorism all over the world and a dozen people are killed here and a dozen people are killed there. It is inconceivable to me that there wouldn’t have been somebody who could have, where were the terrorists when…to destroy this machinery very, very early.

PRINCE: I think you have three different kinds of – more than three but three main groups of people. You have your people that actually do the damage and then you have the people they do it to, the victims, and then you have the bystanders, you know. And I think that people like your father were very few and far between. It does seem that the people that I have met, like yourselves, who knew the difference and who were taught the difference, seemed to suffer the most about it. You showed me a film that’s going to be, and you don’t want to shy away from things. People like yourself who are raised with a sense of right and wrong still carry so much of it with you because it still puzzles and still bothers. And you paid your price also.

BUDER: Yeah. That was just very, very clear to us. It didn’t mix us up in the least to have our parents give us one set of values and the school another. They told us what was happening in the country, that it was all wrong, and that we had to wait it out but we had to be careful what we believed.

PRINCE: You really had a most unusual education and most people are told maybe a little right or wrong but they don’t have a chance to see it and live with it every day and go back home and have it sort of straightened out.

BUDER: Every day, every single day…

PRINCE: Because of the closeness. Obviously you had a really warm family life, but aside from that you had a warm intellectual closeness that most families…

BUDER: Yes, the importance of the individual was stressed greatly by my parents. We, no matter where we were, my parents really had no national feelings whatsoever. They really had very worldly ideas.

PRINCE: Um-hum, but they loved Germany, they loved Germany.

BUDER: Yes, because, well, circumstances put him there and he had learned Greek and some Hebrew and Latin in school.

PRINCE: I take back my statement. (LAUGHTER) I’m wrong to say that to you. Did he love Germany?

BUDER: Well, I don’t think he loved Germany more than another country, no. He just, I think, stayed because of the German language and law. That was his livelihood.

PRINCE: He loved mankind.

BUDER: He loved mankind. The only time my father was in this country, since there was the barrier of the language, he did not like it here terribly much. Things just went entirely too fast, too superficial and everybody was so terribly friendly in the month or so that he was here that he couldn’t find the people that he really should have had something in common because everybody was so nice, but that is the way we are here, you see. So, the German mentality, I think, yes – more reserved people…

PRINCE: And more private…

BUDER: …More private, yeah, that’s a good word, I think appealed to him more, but he had no particular feelings for the “Fatherland” or something. As a matter of fact, my father, as I mentioned, died when he was 72 years old in ’62, and he’s buried in Germany. My mother died while she spent some time with us here. She was visiting us here, and she had told us, “If something should happen to me while I am here with you, then for heaven sake, don’t do such a foolish thing as ship me back to Germany. Have me buried wherever I die.” And she is buried right here which is just wonderful. It’s wonderful for my parents’ relationship. It symbolizes that wherever they are now has nothing to do with German or American soil. And when I became an American, after I had lived here for three years and was eligible for my American citizenship, I wrote this foolish letter to my parents and asked if they would mind if I gave up my German citizenship and my father was almost upset that I would ask such a foolish question. And he said, “First of all, you are you whether you live in Nazi Germany or the United States during peace time or in Red China or in Siberia. I would always hope that you will distinguish right from wrong, that you will work for what you consider good, that you will work against what you consider bad; secondly, you should be a good wife, a loyal wife to your husband; thirdly, the best mother you know how to be to your children, and then, of course, you want to be a voting member, an active member of whatever community you live in. And so naturally, if you expect to live your life in the United States, you need to become a member of that country. It’s foolish of you to expect the protection of a country across the ocean. You want to vote and be an active member of wherever you live.” And so, of course I should become an American citizen, which was a good answer.

PRINCE: Are you like your father?

BUDER: Very much, obviously – yes, yeah. Am I like my father – oh, I’m sorry, I misunderstood. I thought you said, “Do I like my father?” Oh, I’m embarassed at the answer. (LAUGHTER) I liked my father very much. But, am I like my father? Well, I keep those values in mind. It is my experience that my values system goes right back to my childhood. Whatever I learned in school or so might have added knowledge and, sure, experience. But my basic value system goes right back to my childhood.

PRINCE: And they shared it, your parents.

BUDER: That’s a big responsibility for all of us parents to not be wishy-washy with our children but to be clear.

PRINCE: How about Claus? Do you mind my asking about Claus?

BUDER: Well, he stayed in Germany and he was supposed to have been sworn in, into the Hitler Youth.

PRINCE: Because being three years older…

BUDER: Again, everybody who was in school was simply scooped up and on Sundays they were all expected to go to a certain movie theater where they were all sworn in to the Hitler Youth. Sunday after Sunday, my brother, Claus, was sick, (LAUGHTER) and I remember people coming to the house and wanting to pick him up and my mother said, “He is sick in bed.” And she even got a doctor to give him a certificate saying that he had to rest a lot. He was simply sick in bed, so he was never sworn in. He had to attend functions and, as a matter of fact, we both wore things that were considered a part of the uniforms because they were very cheap. They were much cheaper than regular clothing and we were very, very short of money. We never had any money and my father earned so very little that I still don’t know how they really managed. So, we wore a lot those Navy pants and Navy jackets the boys in the Hitler Youth wore. But he was never sworn in because he was always sick on Sunday. Then another thing toward the later years of the war, since he was – it’s true, he looked pale and skinny. He had pneumonia and he had pleurisy. He did have all kinds of things wrong with him during those years. But boys his age were actually picked off the street. So that was another reason why we…

PRINCE: To go into the Army towards the end…

BUDER: …to help fight, yes.

PRINCE: This happened in 1944.

BUDER: Another friend of ours the same age as my brother, Claus, was walking home from school and this dreaded thing happened to him. All of a sudden two SA men or SS men would walk either side of you. A boy would walk along and all of a sudden these two men would walk to either side of the boy and just walk with him, and then he’d never be seen again. And this happened to our friend. The streetcars were still running and these two men started walking to either side of him and he knew what that meant, and he jumped on the streetcar which caught them by surprise, and then, of course, he got off the streetcar somewhere and he and his family had to go into hiding. So those dreadful things did happen toward the end of the war.

PRINCE: And Claus now is living in Germany?

BUDER: He stayed in Germany – well, we were all in Germany then. I didn’t come here til ’56. I didn’t really start enjoying school until after the war. That’s when I really blossomed in school. I just was very quiet and I didn’t get terribly good – neither one of us got very good grades because we were so quiet and probably a little awkward because we didn’t know quite how to express ourselves. So, after the war he was finished very quickly with high school but because all the prisoners of war were then returning, he couldn’t get into the universities, and so he had to work for a few years before he was eligible to start at the university. They went by age to accommodate all the prisoners of war first, to get them back into the universities first. Then he studied law and he’s in a government career now as a lawyer. He’s working in Bonn.

PRINCE: Oh, how nice. And he attended college in Bonn?

BUDER: Right, and he lives in Bonn. I remember my mother saying that one thing that was really obviously clearly missing in Germany after the war was the Jewish element. And I don’t know exactly what she meant by that but I was rereading some letters and it was after she had been here. After my father died, she visited us every two or three years for three or four months at a time and she liked it here very, very much. And when she returned to Germany, she wrote that, “It is very noticeable that in Germany the entire Jewish element is missing in the German nation now.” Exactly what she meant by that, I don’t know.

PRINCE: It could have meant a lot of things.

BUDER: Well, the discipline and the learnedness and the kindness…

PRINCE: The arts…

BUDER: …the arts, all typically Jewish. The immense kindness are typical of the Jewish life. I think that is one thing that she meant.

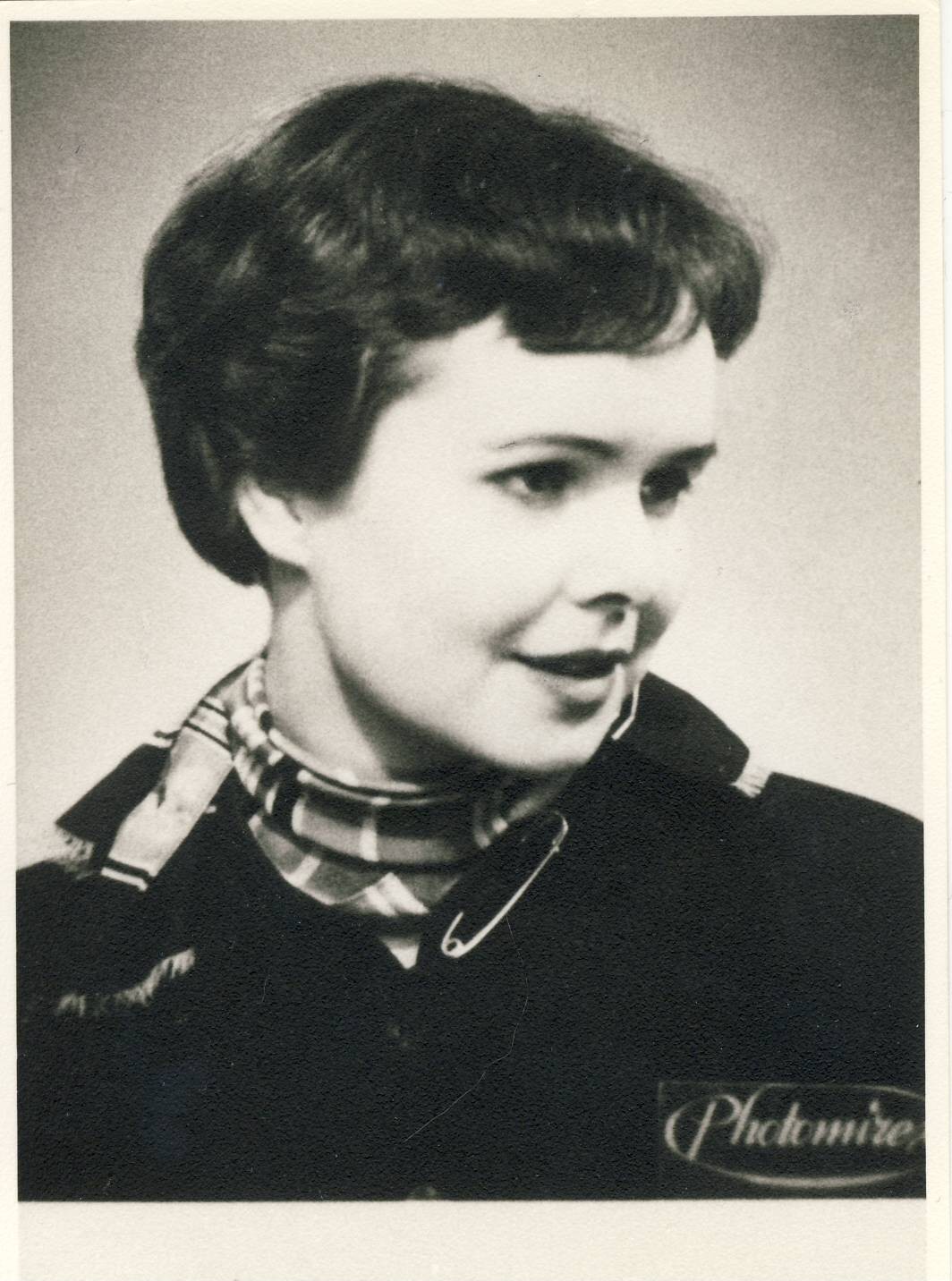

PRINCE: I have some notes written down that I’d really like to go over but we’ve covered a lot. I’d still like you to describe a full school day. I think that’s so important because I see you as a little girl. You know, you’ve lived your life and I’m just listening to it. But when you say thank goodness that you had a chance to talk at home, you obviously had to be very quiet at school. Was that scary for you?

BUDER: No.

PRINCE: Weren’t you afraid that you would say the wrong thing?

BUDER: No, I don’t remember that at all. I just remember that we all had to gather in the schoolyard and, like I said, sing these two German songs and say “Heil Hitler” even to our friends and to the teachers and to everybody. But I don’t really remember any particular hardship or anything that was terribly different. It was very disciplined and we had to be very quiet. The school day was not at all like what I observed when my children went through Community School where the best was brought out in everybody. My parents had hoped to send us to the Waldorf Schools. Do you know the Waldorf Schools? There are Waldorf Schools here in this country. These were founded by Rudolph Steiner who was the head of the anthropological society. There are Waldorf Schools in Detroit and in New York and different cities, and they basically are – they are probably a step beyond John Burroughs, taking in a great deal of nature and learning about the sun and the universe and the natural cycle in this world and how humans have to, or should adapt and respect and work with this tremendous law that exists in nature. Well, there was nothing like that in our school. We sat in our seats and we were taught and our teachers were terribly strict.

PRINCE: They disciplined and not so much expression – just memory.

BUDER: Just discipline and learning. Our math teacher had enormous hands and I remember he would ask you a certain math question. You would have to stand up. He would ask you a question and you would stand at his desk. Then he would leave his desk, with his hand outstretched and he’d walk toward you, making eye contact the whole time and his hand came closer and closer to your cheek. And he constantly was looking at you. You couldn’t think under those circumstances. I remember that. I thought, “If I could only look away or not see him and not see this hand.”

PRINCE: Did he ever strike anyone?

BUDER: Oh yes. He’d come closer and closer and then his hand would just sort of be next to you and “bang!” if you didn’t give the answer. I don’t know what they expected this would accomplish. It was just dreadful.

PRINCE: It must have brought out the worst in the worst people, you know, the teachers.

BUDER: That’s a good point. Yes.

PRINCE: When you were talking earlier about schooling just a few minutes ago, my mind went to some of the teachers who must have been very bad and had a wonderful time during those years.

BUDER: That’s true. The teachers themselves must have all played a role. They certainly were not expressing any real humanity.