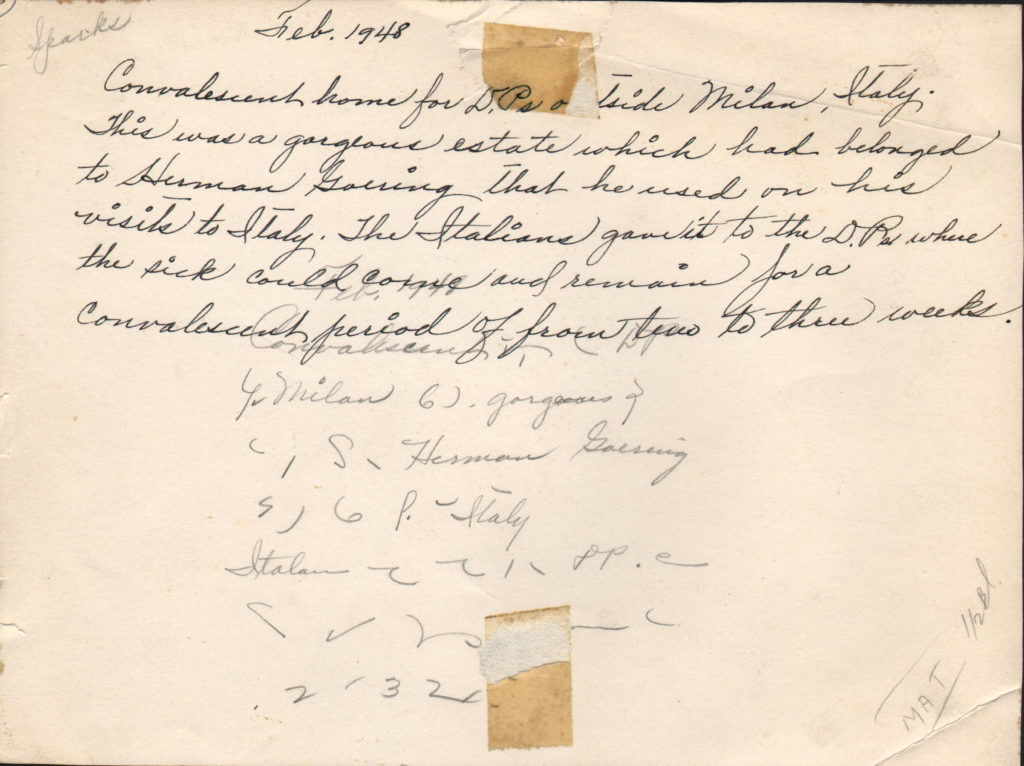

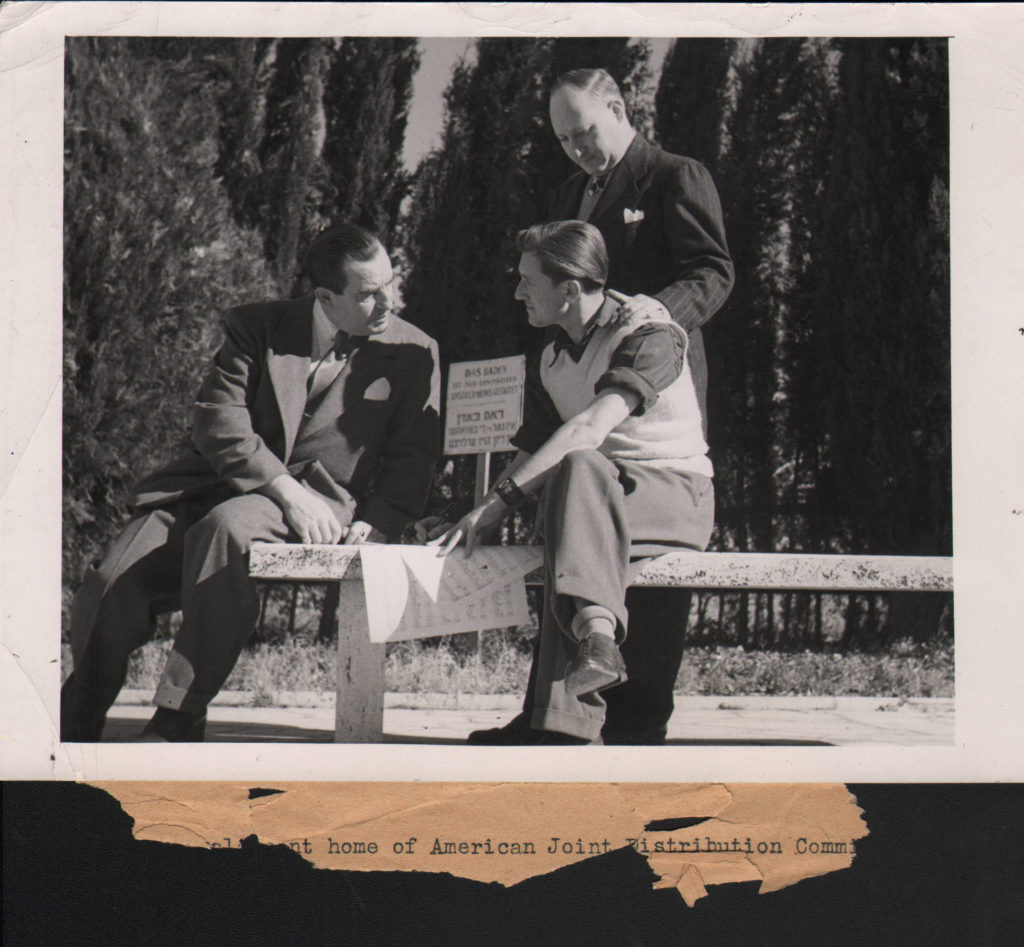

Sam Klein was one of six St. Louisans who traveled through the Jewish Federation to displaced persons camps in Germany, France and Italy in 1948. The group also visited Palestine just months before it became the State of Israel to see settlement projects. Mr. Klein reported his findings back in St. Louis in order to raise money to help Jewish people resettle after the Holocaust. This testimony includes his recollections of his trip to Europe and Palestine.

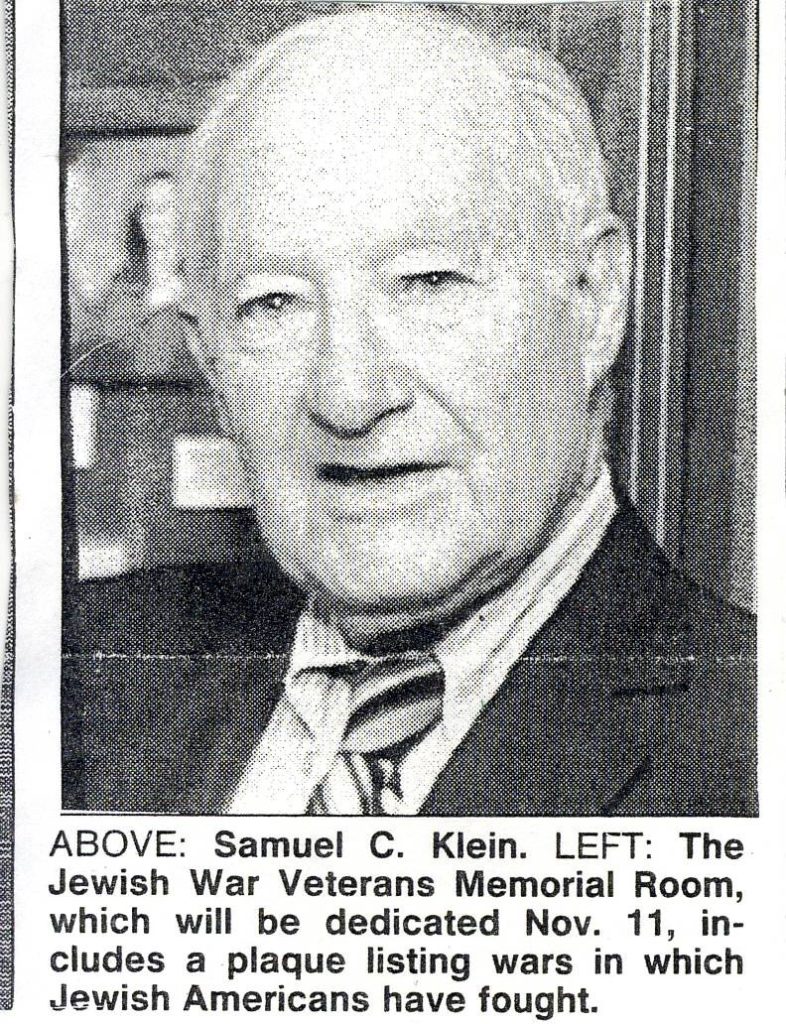

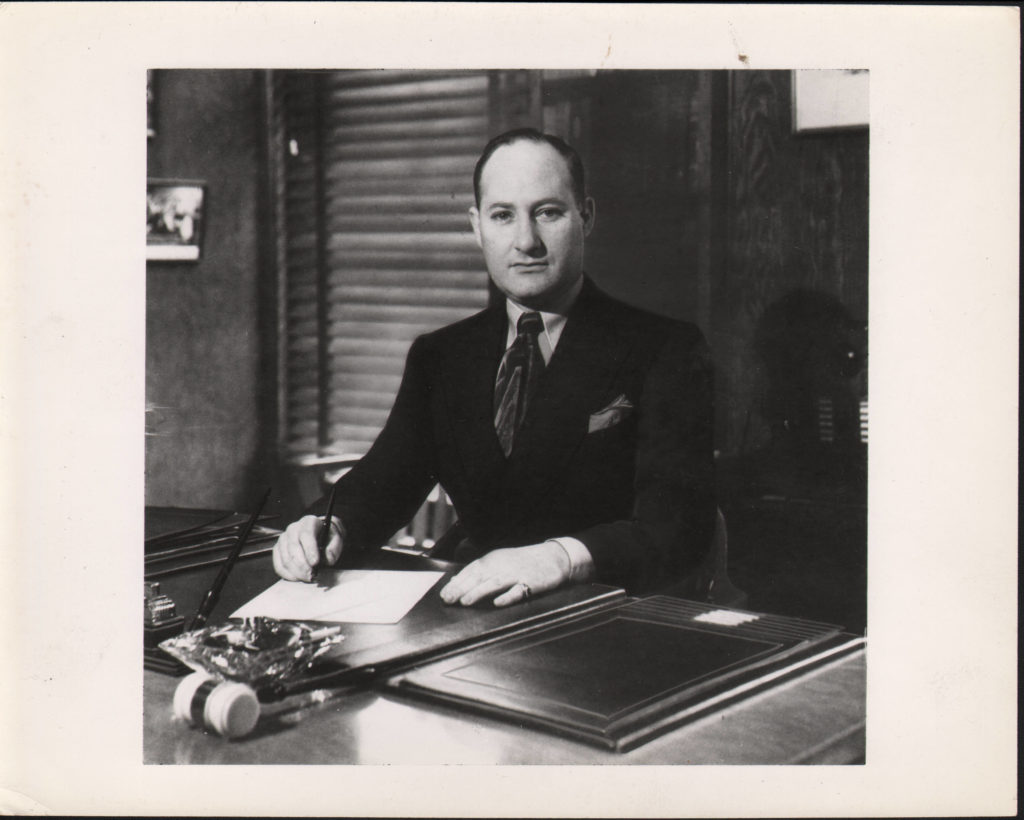

Sam Klein

Mapping Sam's Life

Click on the location markers to learn more about Sam. Use the timeline below the map or the left and right keys on your keyboard to explore chronologically. In some cases the dates below were estimated based on the oral histories.

Read Sam's Oral History Transcripts

Read the transcripts by clicking the red plus signs below.

Tape 1 - Side 1

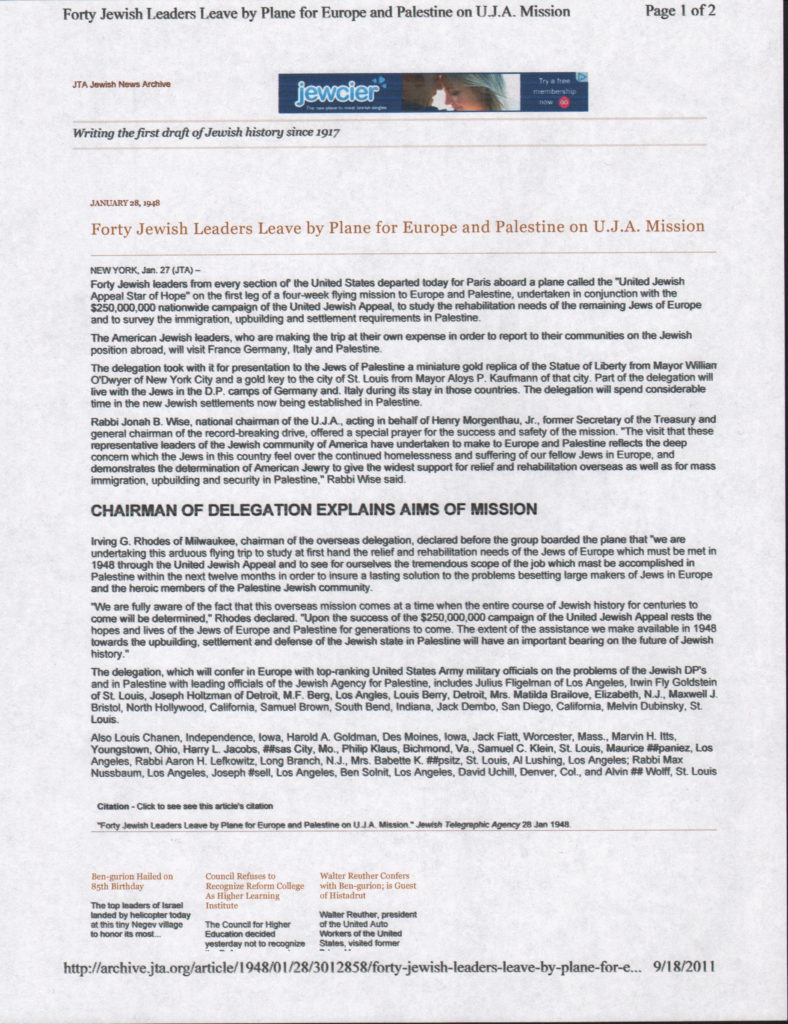

PRINCE: My name is “Sister” Prince and I am interviewing Sam Klein. In 1948 Sam Klein was one of six St. Louisans who made an inspection tour of Europe and Palestine. They visited the displaced persons camps in…camps in Germany, France and Italy and settlement projects in Palestine. They reported back to the United Jewish Appeal, an organization that raises money to help Jews in need. These displaced persons camps were filled with Jewish men, women and children who had been liberated from the Nazi death camps, concentration camps and labor camps, or those who had been lucky enough to have been in hiding during World War II. These camps were a place of waiting until they could find a country that would accept them so that they could start a new life.

Mr. Klein, could you please begin by telling how you were first asked to go on this trip and how you felt?

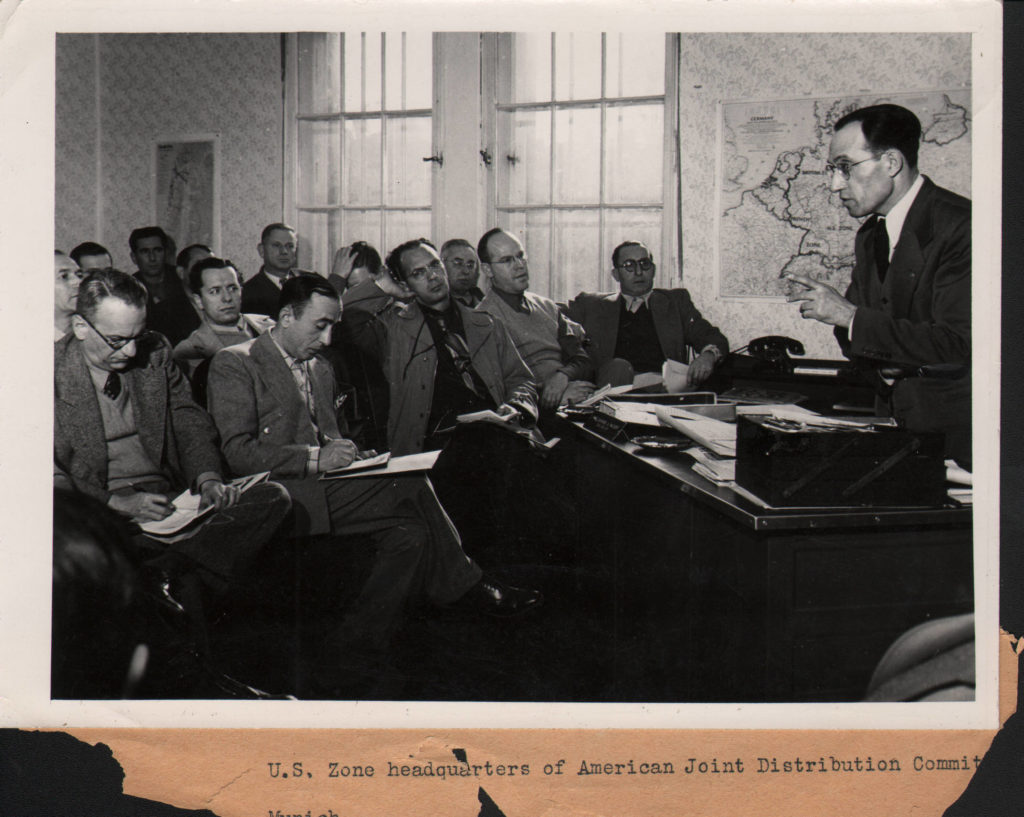

KLEIN: Well, my best recollection is that the folks here in St. Louis, the Jewish Federation selected this group. We represented various phases of business and community lifestyles here, or life lives, in St. Louis and we left from Lambert Field, St. Louis, and we went by TWA and flew to Paris, I believe, was our first actual landing place. We landed several times while we flew, but stayed overnight for the first time in Paris…or it could have been Munich and from Munich we were briefed by Mr. Haben. The name “Haben” seems to stick with me and I recognize that it’s a name that’s familiar in the newspapers today because Mr. Haben who’s an Arab from Brooklyn, New York…Lebanese ancestry…has been Mr. Reagan’s special consultant in the Middle East affairs. But this Mr. Haben that I have reference to was an officer stationed in Munich on behalf of the Joint Distribution Committee, or some similar interested Jewish organization. He’s quite a professional and I believe he’s still alive and around. He was very knowledgeable and we met in his office in Munich, as I recall, together with similar groups from Milwaukee and Denver, and possibly two or three other locations in the United States. When I say “similar,” whose activities in their Jewish communities was the same as ours. Well, we were thoroughly briefed on the conditions that were surrounded, that were prevalent at the time in Germany, and who also prepared an itinerary for us.

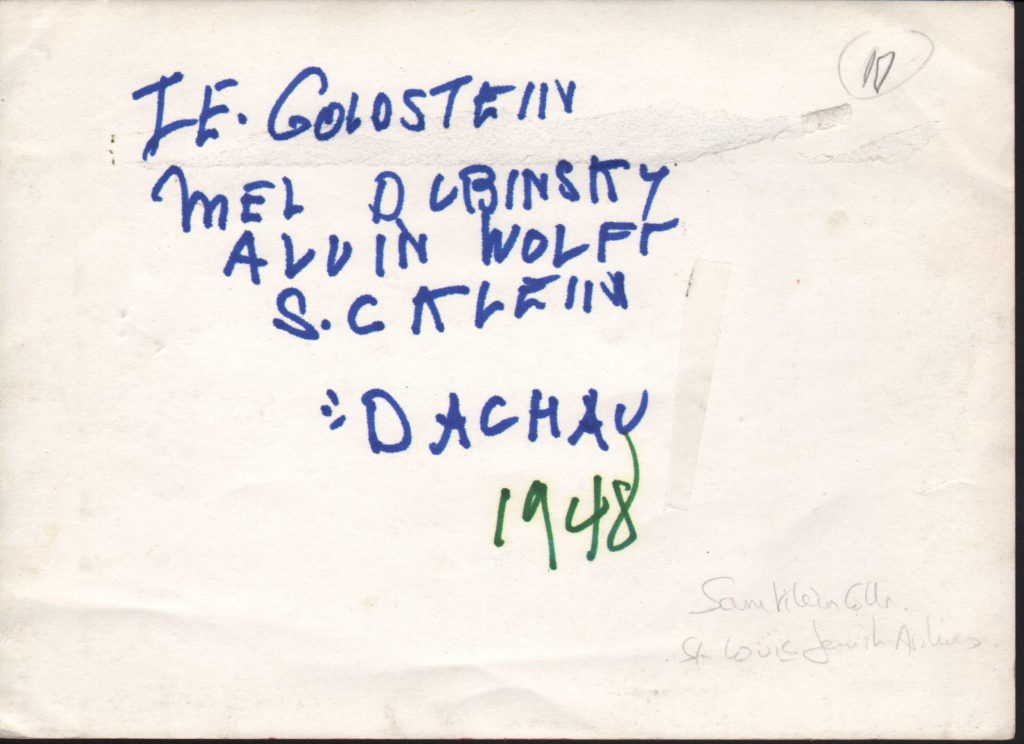

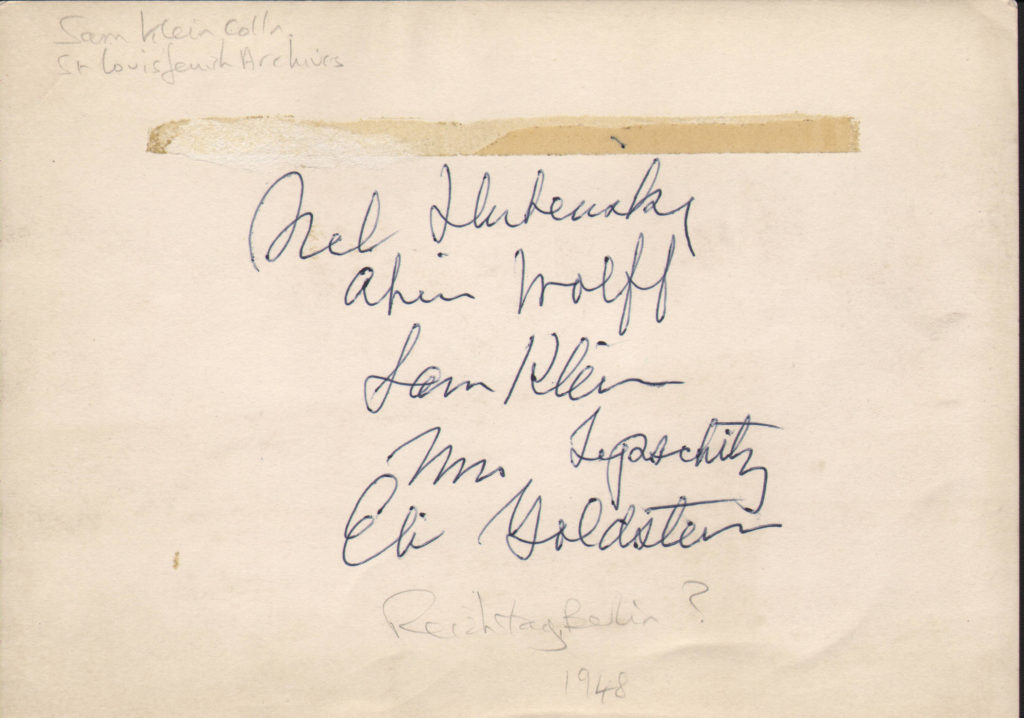

Eli Goldstein was the chairman of our committee, and he had charge of our group and held the itineraries so he might have written copies of them available…I sure don’t.

And we went, as I recall, to Farenwald, which is in Germany not too far from Munich. This was our first D.P. camp and we saw the Jews, the displaced Jews there…children, men and women in great numbers, although completely in my mind, depressed, on the other hand, had a very positive outlook toward what their future might be. They weren’t – when I use the word “depressed,” I would say that they were not down-and-out, but they certainly had been through a great trauma. And an interesting thing about them was, that whatever possessions they had, they had in their pockets. Now, I’m not referring to a comb or brush, or one or two articles of apparel, but they had a handful of photos that they preserved from their wives, children, spouses, or whatever members of their families – what they did probably in some instances, didn’t know what their fate was. And in many instances, knew that they had already been destroyed in the ovens, or otherwise disposed of. Many of them, many of these refugees, men and women, had gotten together…some had married. And it was very interesting to see the manner in which they would tell us about their families. And the new spouse would be equally as interested as they…as his partner or his companion, as the case may have been. I remember one woman calling attention to her husband’s pictures of his children and his previous wife, and they were very helpful in looking ahead considerably to what their future might be. I also remember a very important situation of a man who had his niece with him. He was a lawyer – this man was a lawyer. Now I don’t recall whether he was in Farenwald or one of the other camps.

PRINCE: Landsberg also was…

KLEIN: Possibly, I really don’t remember, but I remember him very well. And he was very anxious…this girl, this niece, was the daughter of his brother who – her entire family had been exterminated and I guess maybe she was, maybe nine, 10, 11, 12 years old at the time. And his concern was how she could survive. The possibility of entering the United States or entering any other safe haven, or any other country, apparently were nil at the time. And…but there was a provision that if the child was an orphan, she could be, she could be accepted in this country. Now I don’t recall, of course, at this late date, in my advanced years, what that legal situation was. But that basically was a fact and so much so, and it’s carved indelibly in my mind because of the fact that this man committed suicide in that camp. This act on this man’s part was an extremely emotional thing insofar as we were concerned because we had met with him in the camp and told him that we were going to do all that we could to be helpful in getting his niece to the United States. However, he apparently was so concerned about his brother’s daughter that he – that he did this thing in order to give her the status of being an orphan. Because it appears that an orphan could be given preference and some priorites in coming into the United States. And I know that this girl did reach the United States and live in New York and subsequently married and has children and probably is in good health, I hope, and in the United States today.

PRINCE: It must have been difficult for you to come from the United States and be thrown into this kind of thing with this depth of feeling.

KLEIN: It, it…that’s right. Speaking of this depth of feeling, I recall when we were in Paris, we were taken to visit a camp of children, small children – four, five, six, seven, eight years old. These were all displaced Jewish children whose folks had been exterminated in one way or another. And it was in the morning – we’d gone to that camp soon after having had our breakfast. I remember this kind of vividly because it was a beautiful and bright morning. And as I watched those children “goose stepping;” now they were “goose stepping” as they were marching around the room because this is something that they had seen the German soldiers do, the occupations and the other allies of the German army…German military. And these kids were enjoying themselves marching and “goose stepping” and having fun. And I said, I recall it very vividly because I walked around the back of the building where my friends who had accompanied us on this mission couldn’t see me…while I shed some tears.

And then as an additional note, I again recall it very vividly, because we would have lunch in France, oh, along about two o’clock. And of course the French are very liberal at lunchtime with their wine and other libations and I guess we all drank a little bit too much at lunchtime because of the fact that uh, uh, uh, it was a method of probably relaxing us. And so when I wrote home to my wife, I told her I visited the camps in the morning and cried, and then got drunk in the afternoon. (LAUGHTER)

PRINCE: I can’t even imagine…was it, was it – how did it measure to your expectations before you…?

KLEIN: Well, it was shocking for us to actually see the situation. I say “shocking” for us to actually see it. We had read considerably about the indignations and atrocities that had been practiced on the residents of the camps, particularly women who were experimented upon by Nazi doctors without being properly anesthetized for whatever – improper, illegal and indignant surgery that was being used as you would in our laboratories here – on animals. And I talked to some of these women and these were, all of whom carried tattoos on their arms and who explained what had happened to them and how despite the hardships many of them had entailed, were determined to attempt to live and see that Judaism was not stamped out. This, I believe, was one of the reasons why so many of them had remarried in camps. Because I guess it was not an experience that helped them as partners to look ahead to the future and attempt to put behind them all those indignities that had been imposed upon them for so long.

PRINCE: An affirmation of life…

KLEIN: An affirmation of life is absolutely true. Life for themselves and life for their descendants, and their people.

PRINCE: Your trip consisted of, was it a month? Is that what…

KLEIN: Uh, I believe it was about a month. I know (LAUGHTER) that I received a cable from my wife in Paris on my birthday which was January 30th and I did call her from someplace in Europe, maybe a couple of weeks thereafter. It was close to a month and a half we went to – after we got through touring the camps – we went to camps in Italy where we found the pattern was the same, the pattern was the same. I remember together with one or two others in our particular group, standing at the ovens at Dachau with the chute where they shot out the ashes and remains…stood there at Dachau. I remember in a museum that the army had developed, I believe this museum was in Germany, where there were bars of soap under glass. This was soap created from the remains of Jews who had been boiled down or whatever process they used, because of the shortage of soap, and whatever materials go into the making of soap. And they made them from the bodies of dead Jews.

PRINCE: Did you want to go to Dachau? You were there so soon after…

KLEIN: Well, you said, “Did we want to go to Dachau?” I guess we didn’t want to go anyplace after the first stop. But the facts are this was part of the itinerary and part of us being able to view firsthand and be able to tell on a personalized basis. And certainly in much greater and better detail than I’m relating it now, uh, some 40-odd years later – so that people in this country who were being asked to make contributions of money and other substantial methods to be helpful to these people behind barbed wire so that they could hear it first-hand from us. Many of us spread throughout the country and made talks to interested Jews in other cities. And we were able to say, “I saw these people last week, I held their hand last week, or two weeks ago,” as the case might have been. And rather than the newspaper stuff, because what we read in the newspapers, the atrocities were so violent, so vicious, particularly the experimental surgery and the marching people out – the men and women out in the middle of the night, in the dead winter. And having them strip naked so they could experiment on what the cold weather would do…whether they would freeze and be able to be thawed out. And I know that I sound, almost I guess for people of this generation here in 1983 and 1984, that it seems almost unbelievable, but this had been done by human beings, one toward another, but those are the facts as we saw them and heard them first-hand.

PRINCE: Thank you. I know this isn’t easy to talk about. Let’s go to the camps and if you could tell me, in 1948, how were they run? Who was in charge of these displaced persons?

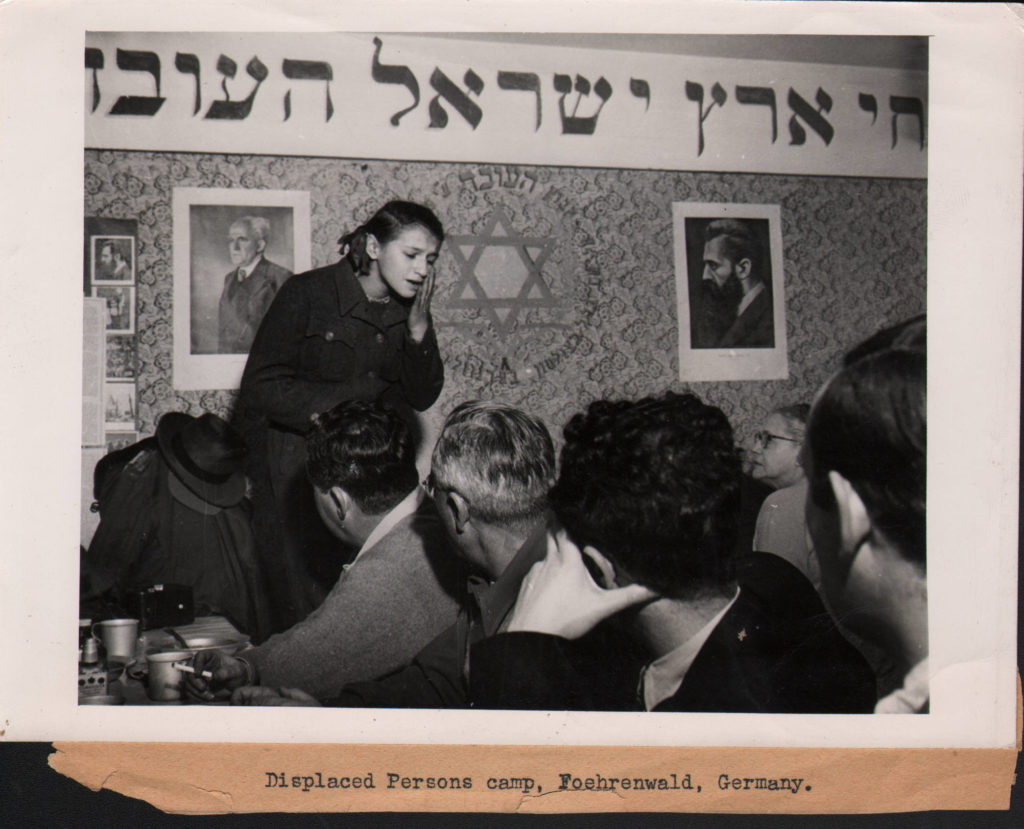

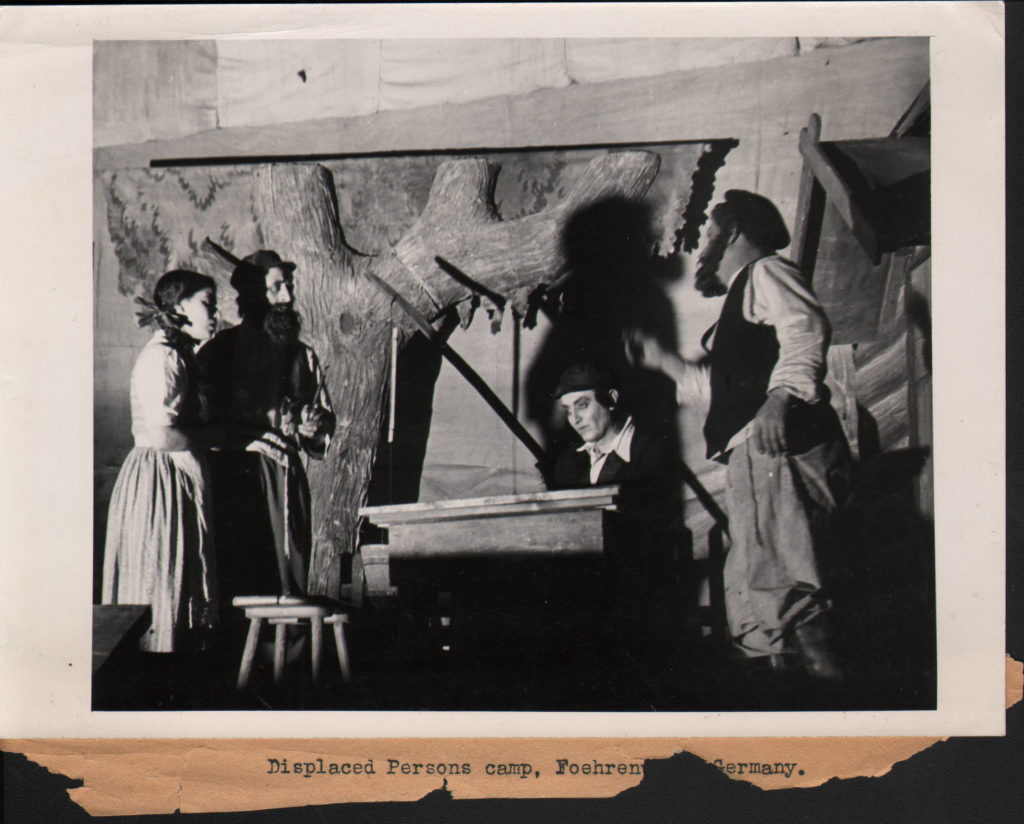

KLEIN: The camps were administered by the United States army who…an officer in the army would be in charge of the camp. I didn’t see too much army personnel; it didn’t require too much personnel as I reflect on it now. These people were orderly. When I say “these people,” I’m talking about the survivors of the Holocaust. These Jews who were interested in keeping alive and they did this. They had theatre. They organized orchestras and bands and had music. They didn’t have the best instruments, but whatever they could salvage, whatever they could muster, they did. And we went to some auditoriums that they had constructed hastily there themselves in the camps where they entertained at night and played the piano, sang, and as I reflect now, I can recall one young lady who just tore our hearts out with her beautiful rendition. It upsets me now as I reflect on it, but be that as it may, they had schools that they organized. They’d find teachers from amongst their groups so that they didn’t require too much military. They just required some organization and somebody had to be responsible for them. And I personally found some officers, and I remember very well speaking to one of them, and I’ll relate that incident. Now these folks were living in small homes. I don’t know if “homes” is the proper word…

PRINCE: Barracks?

KLEIN: Some…many…most…in barracks. But then there were some small places, like individual resident type of thing. But it was a camp, no question about that. And –

PRINCE: Could they come and go as they wanted?

KLEIN: They could come, they could come – they had to get passes to get out of this thing. They had to get passes. Military is military. They’re just not too courteous in most respects…they weren’t then. They probably have improved now.

PRINCE: Excuse me. One question before I forget. Could they leave and disassociate themselves from the camp if they wanted to?

KLEIN: I’m not sure about that but I think that they…there was probably some arrangements could be made if they were able to spell out in detail who would be responsible for them, where they would go and who would take care of their upkeep and so on.

PRINCE: Or was this camp just a place if they wanted to get a visa to the United States or to somewhere else, or otherwise could they just…or do you know this?

KLEIN: I spoke earlier about them having their possessions – their documents. Now they carried all of this stuff. If they had a relative here in this country, they had the names and addresses as best they knew them and whatever. And this was all for the purpose of being able to get out and get a visa.

I remember there’s a family here in this country, well-known. (LAUGHTER) The Allan family, who before I left, gave me the location of a brother of the senior Allans. These Allans I’m talking about now are the ones that are here, are all the children and the grandchildren – but this was the brother of the senior Allan who was alive then; who told me where his brother was, and that brother’s daughter. Now I found them, I found them. It wasn’t easy but it’s just one of those things where you get a lucky break and they showed me letters. And I remember those so vividly because there were letters from Rice Stix that they had attesting to the character of the family here and the family’s ability to sustain these people if they could get a passport or visa, or whatever. Their origin was from Poland and at that time I was aware of the fact that the Polish quota was oversold, so to speak. I computed in my mind that it would take them 20 years to get here on the basis of that computer. I’m very glad to be able to say that in about two or three years they did get here as things, apparently the quota may have been liberalized or whatever condition arose, but they did get here.

But these folks all had, in their efforts to survive and their efforts to look ahead and get out of the camps permanently and come develop a new life, they carried their few possessions which was probably a big old manilla envelope or faded wallet – just with pictures of the family and whatever documents they could find. And most of us were asked to try to locate relatives for them and they’d have a name. And invariably, it would be a name in keeping with the origin of their country which their relatives who preceded them to this country many years before had Americanized and Anglicized, or however. So it was most difficult but we did in some few instances find some people for them. But they had a sense of freedom in the camps that they could do pretty much as they pleased within proper regulations. But it was still camps and barbed wire no matter how you figure it.

I recall on one occasion that distressed me at the time, we were – there was a colonel, an army colonel who was showing us around the camp and explaining all of his virtures and all of his kindness and so on. But the thing that bothered me to the point where I finally talked to him about it, he would go up, knock at the door, and then walk right in. Now, it could have been a handful of women in there. It didn’t make any – he just knocked and walked right on in. And I asked him about it, but of course I didn’t get a very satisfactory reply.

PRINCE: Yeah, not too much sensitivity there.

KLEIN: No.

PRINCE: When you were talking about the fact that the survivors had theatres and schools and kept trying to teach and to live, it made me think of even when they were in the ghettos, they did the same thing, as much as they could, I mean. Then you went on to stay that they could pretty well do what they wanted so there was of course, but…

KLEIN: The ghetto lock wasn’t there.

PRINCE: Right. But they still went for it, so to say, in a way that…I guess that’s why they survived.

KLEIN: That’s true.

PRINCE: Uh, they could not, they could not go back or did not want to go back to where they had come from before?

KLEIN: I found no evidence of that in any shape, manner or form.

PRINCE: Poland, Germany, Hungary?

KLEIN: No. Not at that time, not at that time. No.

PRINCE: They wanted out?

KLEIN: They wanted completely out and so would you and I under those circumstances.

PRINCE: Exactly. Uh, along with running the camps, I, correct me, but were there Jewish organizations that were also filling in with clothes and teaching them skills?

KLEIN: I’m sure that there were because it was – I said in the very beginning about the man that briefed us and he was a professional from the Jewish Organization of the United States and they were as helpful as they possibly could be, under those circumstances. The unfortunate thing was the undue length of time in which they were kept in the camps. And this was brought about by reason of the fact that no countries would accept them and turned them away if they left the camps and arrived illegally, so to speak, on boats that were bringing them over. Well, at any rate, they had to wait until quotas were lifted. And I think the best way I can point out is my statement earlier indicating that I thought it would take them 20 years to get in from Poland based on the quota at that time. And I’m glad to be able to state that these folks did get here within a couple of years.

PRINCE: Could you tell me what non-Jews in the communities that these displaced camps were in, did they have any feelings? Did you ever have any conversations with them about what either went on or how they felt about those camps now?

KLEIN: Well, actually in my particular mission at that time, we didn’t get into contact with too many non-Jewish citizens in the countries we were checking on, except perhaps waiters, waitresses, restaurant help and so on. All of whom professed to know nothing about it, and showed pretty much, had the same indignation that many of us had, and also the great disbelief that anything like this could happen in their country, and how horrible it was. But no one seemed to understand, seemed to know that anything was going on as terrible as Dachau, Auschwitz and all the things…Treblinka…that those names indicate to us who have experienced seeing it firsthand.

PRINCE: I suppose they were trying to put their own lives back together, such as they were.

KLEIN: No question about that. That they were trying to disassociate themselves and divorce themselves from those conditions and get as far away from it as they possibly could.

PRINCE: All right. Could you tell me what impressed you most about this trip, or I can put it two or three different ways – and you can pick how you want to answer it. What couldn’t you forget when you got home?

KLEIN: Well, I guess what I couldn’t forget might – might be indicated on tape that I made, because I believe my voice faltered once or twice as I relived some of those occasions, particularly, the occasion one night where the young lady or a child about 14, 15 – it’s difficult to gauge ages because most of them were underfed and not in good health conditions – sang a song for us where she was indicating her desire to go to Israel or to Palestine as it was then known. And it was sung in such a manner as to draw the tears from most of them that were there and it stayed with me. And the situation that I described about the camp inmate who killed himself so that his niece could survive. And there were many of these stories – many I’ve already forgotten as we tend to want to erase these things from our mind, as times goes on. But there were many unfortunately and these are things that we recall. We couldn’t understand how violent, vicious man’s inhumanity towards man could have manifested itself as it did during these days in Nazi Germany.

PRINCE: Now, all right, let’s move ahead. And you then went to Palestine?

KLEIN: Yes, we went to Palestine. From there we went on an army plane. The United States army funished us the pilot, military personnel, to take us to Lydda. That was the airport that we were going to. The reason that we went in an army plane was because there weren’t any civilan planes, airlines, any airlines flying into Palestine at that time. We landed in Greece. We had no visas or passports or other documentations for Greece, so we went to Athens. It was nightfall at that time and the pilot didn’t want to proceed on to Lydda because he understood that there was some shooting at the airport and he wanted to fly in during the daytime so he could see what was going on. One or two of us were able to bribe – and I hate to use that word “bribe,” but I really didn’t have…and one of the immigration officers who got a jeep there at the airport in Athens and took us down and showed us the town. They did take the precaution; his sergeant did take the precaution of withholding our passports. He kept them until we came back and picked them up. We came back pretty early in the morning just in time to board the plane and fly on to Lydda.

Now, we arrived in Lydda and here again we had to wait. We were held up considerable lengths of time and then subsequently, much to our surprise, a caravan of armored cars came for us and took us on in to Tel Aviv. Then we learned, at that time we learned, that the reason for the waiting for the armored cars to take us was that there was considerable shooting and sniping on the road. Now when I used the word “armored cars,” at this point we think in terms of the Brinks trucks and the armored cars that we have. These were old trucks with sheet metal or something that the Palestinian Jews had put together so that they could do things of this kind. We were stopped several times on the road for inspection if we were carrying arms. This was by inspection of the British army who, at that time, it was still British mandate. Their inspection certainly wasn’t very probing because we, arriving with these trucks were Palestinian youths, both boys and girls who acted as our bodyguards and who were armed. They were armed with homemade Palestinian stenguns which they disassembled and when the inspector came aboard, he gave us a very cursory inspection and the things were all hidden behind their skirts or one way or another and then quickly assembled, or reassembled so that we could proceed in safety.

An interesting antidote and concerning these people is that when we got to Lydda, we went to the Katy-Dan Hotel. And at the hotel, our group leaders and others asked that we not leave the hotel that night because there was shooting going on and didn’t think it was safe and so on. I felt I hadn’t come that far not to be able to get out and go up and see what was going on in town, because I could see that the main street was pretty well lighted. And I walked up the street to Allenby Road and I was walking along, there was a barber shop there and several barbers. These stores were open late at night. It was dark. I don’t know…remember the time, but probably easily about seven or eight o’clock at night. Maybe even nine, and I saw two or three barbers standing over one man in the chair and he…one of them was talking to him and I recognized this man was also in our party, but hadn’t consulted us about going out. And the barber asked him if Mr. Morganthau was with us. Now Mr. Morganthau at that time was Secretary of the Treasurer. (LAUGHTER) I didn’t identify myself. I didn’t even go in. I went to a store, a bake shop, a bakery and this was a beautiful bakery. And it had on display in the windows – it had a great big cake. Oh, I’d say four foot long and four foot square and you bought it by the kilo. And then I decided since I was the adventurous one that I was giong to go in there and buy some bakery stuff and bring it back so the egotistical thing I did to show my friends that I was out. (LAUGHTER) So I went in and the store was crowded. There were people to be waited on. And the man, apparently the owner of the shop, saw me and came right over to wait on me. I was a little embarrassed by this because here all of these other people were ahead of me and I said, “Well, I just got in here and these other folks are ahead of me.” He said to me, “I know who you are.” And I said to him, “Well, who am I?” He said, “Well you were in the caravan that I helped bring in.” And this utterly amazed me because I thought of the line…the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker. And I used it in making a verbal report to a group, when we made our verbal report at the Kiel Auditorium, and I told them it was the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker.

PRINCE: It did it all.

KLEIN: It did it all – right.

PRINCE: I think it’s fair that just to note here that when you came in to Palestine, it was February, I believe of 1948, and it wasn’t until May when they became the State of Israel. So that the sniping and the Arabs taking pot-shots was not peculiar then, and of course, it’s not peculiar now.

KLEIN: Yeah…we…(LAUGHTER) It was kinda standard procedure there. Everyday we heard the shots. Everyday there was shooting. And the one thing that distressed us, we just felt that the Jews in Palestine were really trapped in their own enclaves and because they would be overrun by the Arabs, militarily, they never at any time indicated any fear of that. I just couldn’t understand how they could be so confident that they wouldn’t be overrun. And of course the facts soon developed that just eight-nine weeks after we left there, the Arabs did attempt, various Arab nations did attempt to overrun them – that they were using cowbells and bullhorns and whatnot. And picking up the guns that the Arabs left and was turning them on the Arabs, and were having pretty much a decisive victory at that particular time.

PRINCE: What did you see in Israel, I mean in Palestine? You went to see the settlements that the new immigrants worked in.

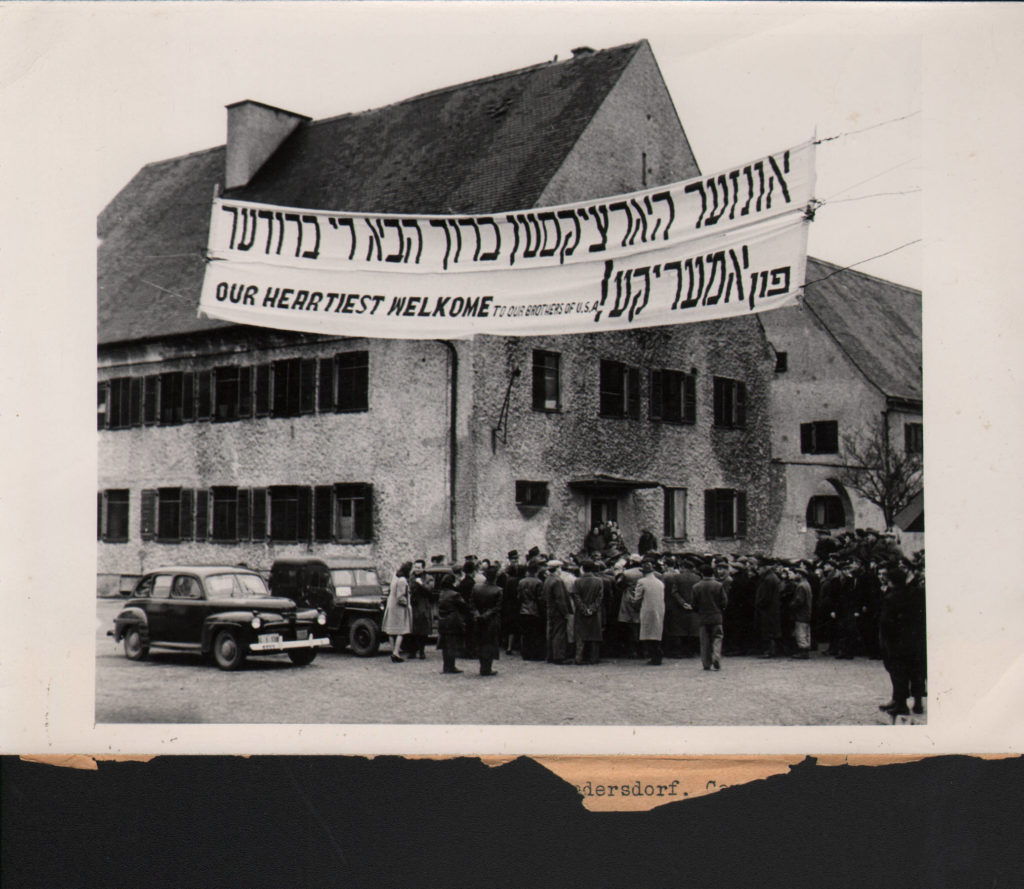

KLEIN: Yes, we went to see the settlements and the new immigrants. And again, I’m now reminded of my report that I gave because when we got to the first stop, of course, for the survivors that were reaching Palestine was a big camp, very similar to some of the camps that we have except it was absent barbed wire and it was absent any military and, but it was temporary housing and until they got more substantial housing for them. But there were great big banners – great big banners spread over the gates of the things, that were Hebrew letters. And I asked a friend to tell me what it said and it said, “Welcome.” It interpreted from Hebrew to English as being “Welcome.” And I told my friends here in St. Louis that they wanted to go to their country that “welcomed” them.

PRINCE: How nice – how special. Were they coming in legally then?

KLEIN: Well, they were coming in both…both legally and illegally.

PRINCE: There was still a –

KLEIN: Yes – trickling – they were always trickling in illegally because different countries had their different backgrounds, different nationalities and many of them didn’t have – didn’t have the help that was given to them by the Joint Distribution Committee and others. So that was the majority, I believe, was legal but many of them came in just to get away from the conditions that they had been living under the past several years.

PRINCE: Okay. Coming from Europe and seeing all the Jews and the D.P. camps, going to Palestine, seeing them in resettlement, knowing that you were actually seeing some of those Jews who had found a home, uh, that must have been almost exhilarating. And how did you feel being in Palestine, yourself?

KLEIN: Well, I did feel real good about it, no question about that in my mind. And I again touched on it earlier when I spoke of the spirit of the people, of the Jews of Palestine. This was their country! They weren’t the least bit concerned about being able to defend it, although they didn’t have at that time all the arms and weaponry that they have today. But they felt that they could defend it and that they could make it a democracy and that they were anxious to have a democracy. And the youth of Palestine…the exuberance of the young women. I have in mind one girl, Judy, a little girl that wore bobby sox and tennis shoes who was one of our escorts in coming over on the convoy from Lydda Airport that I described earlier. There were many like her and her counterpart. I can see her visually now standing with her stengun and her clip of ammunition. But these were, in my opinion, like any American bobby soxer. “Bobby soxer,” which was an expression that was common some 40 years ago in this country. She was, no doubt, just in my mind, just the same as any bobby soxer here in Ladue, Clayton, or in St. Louis. But she was a part of the times and conditions and environment that existed there when these Jews that were determined to have a country of their own so that never again, as Begin said recently, would there be a Holocaust.

PRINCE: Now it’s time to go home and you came home and you each, I believe, made a report at Kiel Auditorium for the express purpose of raising money to help these people that you had just seen.

KLEIN: That’s right. We, I’m glad to be able to tell you that the Kiel Auditorium was crowded…crowded. And the late Rabbi Gordon was the chairman of that meeting and the local people here and all the six of us that participated were invited. We each were assigned a topic to speak on and I believe that mine was to speak on Palestine, and I did. And I remember well my closing words which were, “They want to live in a country that cries out to them, ‘Welcome, welcome.’ They want to be fishermen in the sea, tillers of the soil, architects and builders!”

PRINCE: Thank you. Thank you very much. I appreciate your time and your words.